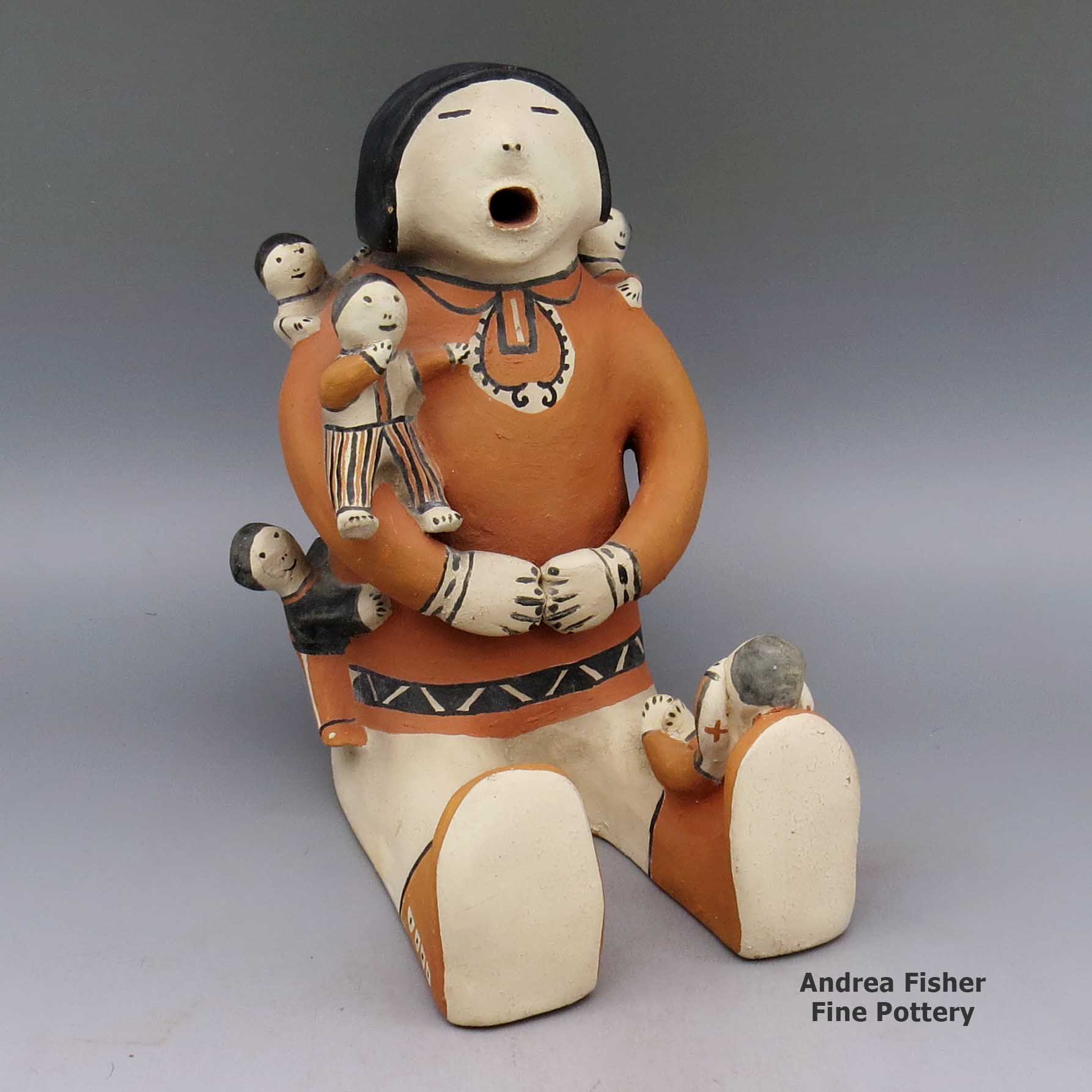

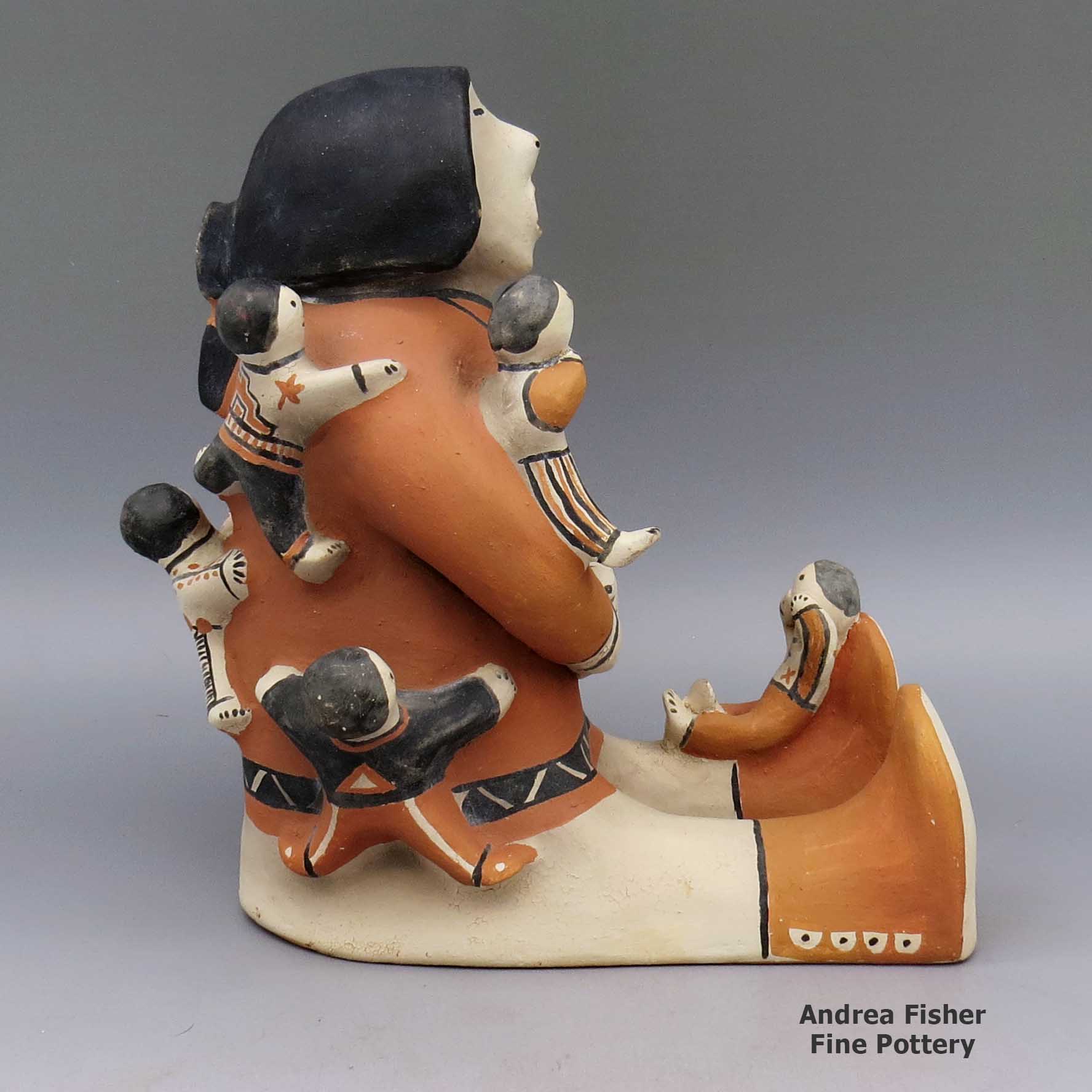

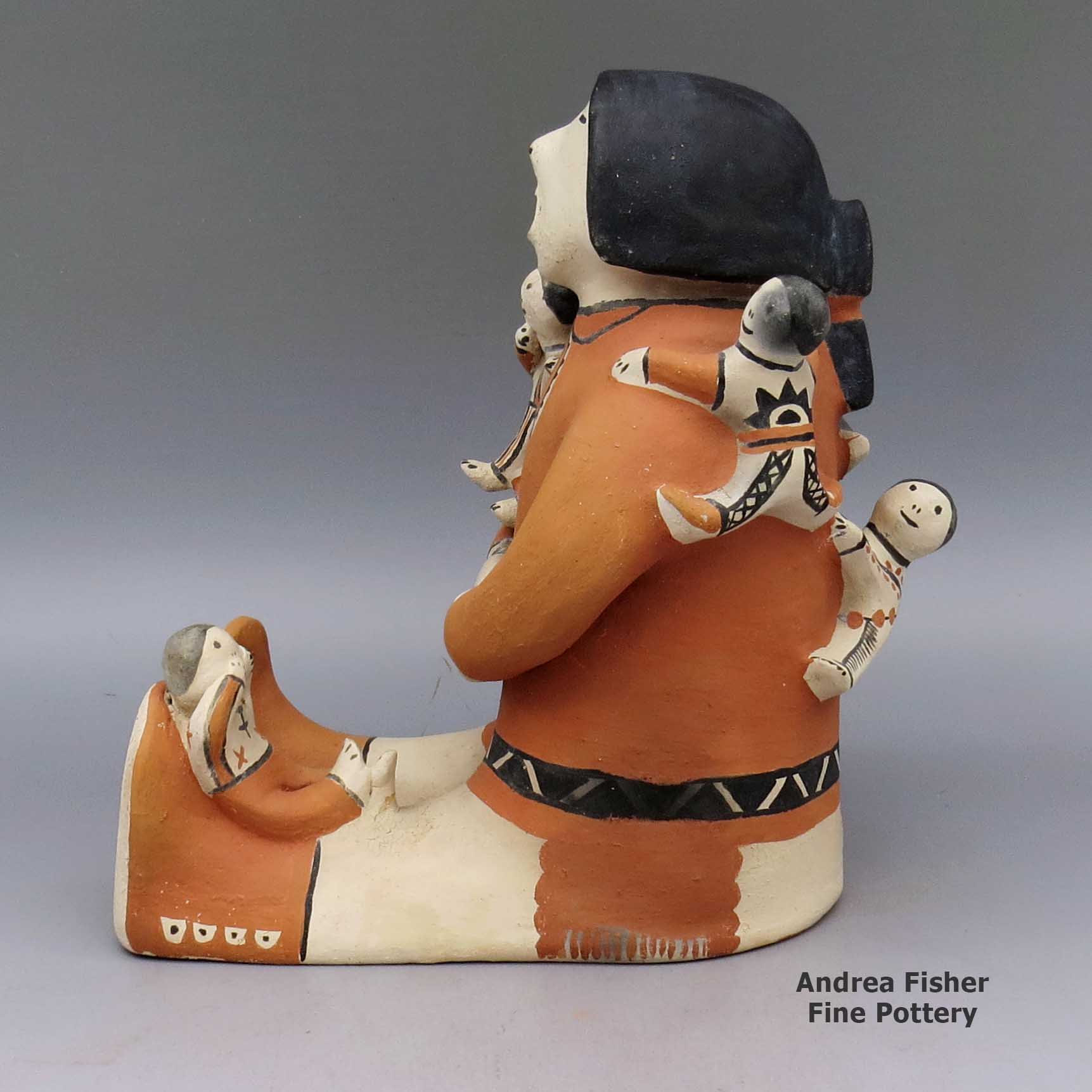

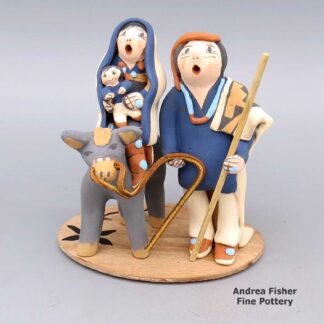

| Dimensions | 10 × 6 × 10 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has paint flaking, rubbing on bottom, and normal wear |

| Signature | George Cordero Cochiti, N. Mexico |

George Cordero, lkco2l321, Storyteller figure with six children

$2,650.00

A polychrome grandfather storyteller figure holding six children

In stock

Brand

Cordero, George

Helen was not satisfied with her pottery career at first, then she made her first storyteller figure in 1964. It was like a light bulb lit up in her heart and she instantly knew what she was meant to do. George was 20 then. A couple years later he got interested in what she was doing and began to work with her.

George, too, first started making polychrome jars and bowls, then learned to make storytellers in the early 1980s. He also made turtles, drummers and other figures. He often collaborated with his mother. His work and hers so closely resembled each others the only way to tell them apart was to turn them over and look at the signature.

George and Helen passed their skills on to his daughter, Buffy Cordero, and she became an excellent potter in her own right.

Some Exhibits that have featured works by George

- Gifts from the Community. Heard Museum West. Surprise, AZ. April 12, 2008 to October 12, 2008

- Passionate Involvement: Recent Acquisitions of the Heard Museum. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. March 1, 2001 to October 1, 2001

A Short History of Cochiti Pueblo

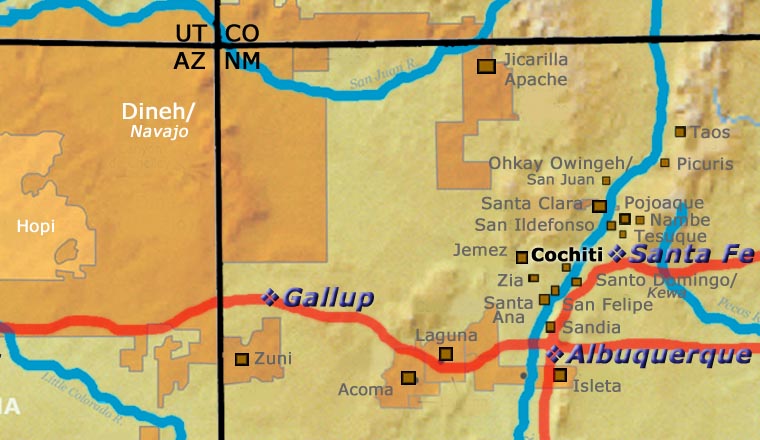

Cochiti Pueblo lies fifteen miles south of Santa Fe along the west bank of the Rio Grande. What is now Bandelier National Monument is the pueblo's most recent ancestral home. They may have relocated to the Bandelier area from the Four Corners region around 1300, and then closer to the Rio Grande in the 1400s in the heart of an even worse drought situation. They merged with people who had been living in the area for hundreds of years before, pushing south until they came up against the countryside of the Tiwa pueblos in the middle Rio Grande.

In those days, the people of Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe were one Keres-speaking culture. They split into three cultures when some decided to go further down the Rio Grande to settle (San Felipe), and some decided to cross to the eastern side (Santo Domingo). All three speak dialects of Eastern Keres and are considered very conservative.

Cochiti legend says that Clay Old Woman and Clay Old Man came to visit the Cochitis. While all the people watched, Clay Old Woman shaped a pot. Clay Old Man danced too close and kicked the pot. He rolled the clay from the broken pot into a ball, gave a piece to all the women in the village and told them never to forget to make pottery.

Most outsiders who visit Cochiti Pueblo these days do so on the way to or from either the recreation area on Cochiti Lake or Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument.

For more info:

Cochiti Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Cochiti official website

About Figures and Figurines

Generally, "Figure" denotes a real or mythic creature, like an owl or human or katsina or Corn Maiden. Whether form or decoration, all Puebloan pottery figures are meant to invoke particular spiritual essences. That's why "effigy" is used almost as often as "figure" to denote these pieces.

Among most Puebloans, the figure of an owl, for example, signifies all the physical and spiritual aspects attributed to the owl. It's a form of prayer to the spirit of "Owl" and the appropriately decorated physical form is meant to make that spirit manifest. However, to the Zuni people an owl is a good omen and to the Tewa people, an owl is a bad omen. Some potters at Santa Clara have made owls anyway, they just shaped and decorated them to reflect that "badness."

That explanation may make more sense in the case of the Corn Maiden as she is a mythic entity whose existence revolves around the most ubiquitous food staple in the Puebloan world: corn (maize). All representations of the Corn Maiden are meant to invoke her benevolence and abundance for their people. Because of her mythical/spiritual nature, different pueblos have slightly different physical forms for her but they all incorporate the basic form of a female human face on an ear of corn.

The potters of Tesuque turned out thousands of muna figures (also known as rain gods)for several decades, until they virutally burned out their pottery tradition. These muna had very specific shapes but were decorated with everything from micaceous slips to incised lines to polychrome geometric designs to poster paints. They were also made purely for domestic American consumption, sometimes delivered by the barrel to be used as prizes and giveaways.

The Storyteller is another figure based on Puebloan tradition: a tribal elder singing the stories of the tribe's oral history to the children. The original was based on the traditional cultural story: a grandfather singing his part of the story in his native language so the children learn both the language and their identity against the backdrop of that history. Shortly, the storyteller form was duplicated in several other pueblos, each pueblo's potters adapting the form to their local situation. In some places, the grandmother became the primary sex of their storytellers. At Jemez, that responsibility was shared between grandmothers and grandfathers. Then some potters in search of new niches in the marketplace branched into making "spirit figure" storytellers, like eagles, ravens, hummingbirds, cats and dogs. Some Zuni potters have made storyteller owls.

Similar to the Storyteller is the Story Time: a set of separate children displayed around a larger central singing figure.

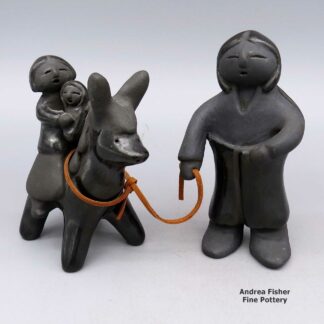

The Nativity set (also known as nacimiento) is a set of figures based on the intersection of Puebloan mythologies and stories they heard from Christian missionaries. Those potters who make them also tend to favor dress, shapes and designs that reflect their own heritage(s). The first few nativities made at Tesuque Pueblo were decorated with Spanish colonial costumes but that soon changed and every nativity made since has a distinct blend of Native American and Christian, with no other reference to colonialism. The "Singing Angel" (a single standing figure with outstretched wings and hands clasped together in prayer) and "Flight to Egypt" (usually depicting Mary with a baby Jesus on the back of a donkey and a standing Joseph nearby holding the rein) are similar mixes of tribal and Christian figures. The miniature nativities made by Santa Clara/Dineh artist Linda Askan clearly show Dineh religious influence in the headresses worn by Joseph, the angel and the three wise men. At the same time, the Dineh Folk Art nativities made by Jonathan Chee are based on the realities of daily Dineh life: the three wise men wear wide-brim hats and blue jeans, and bring gifts of salt and 50-pound bags of flour.

Pueblo and Dineh artists also make a full zoo of domesticated, farm and wild animal figures: horses, donkeys, cows, chickens, pigs, sheep, turkeys, giraffes, elephants, dogs, cats, mermaids, women-dressed-up-and-taking-selfies and cowboys among them.

About the Storyteller

Historically, clay figures have been present in the Pueblo pottery tradition for more than a thousand years. However, figures and effigies were denounced as "works of the devil" by the Spanish missionaries in New Mexico between 1540 and 1820. Before and after that time the art of making figurative sculpture flourished, especially at Cochiti Pueblo. At Cochiti, the forms of animals, birds, caricatures of outsiders and, more recently, images of mothers and grandfathers telling stories and singing to children have multiplied.

The "storyteller" is an important role in the tribes as parents are often too busy working and raising kids to pass on their tribal histories. The Native American people did not develop a written language to record anything for posterity. Some tribes still refuse to create one. The closest thing they had to a written language was recorded on pottery and textiles, in the form of painted designs that decorate that pottery and textiles.

The storyteller's role was to preserve and retell and pass down the oral history of his people in their native language. In most tribes that role was fulfilled by elder men.

The first recorded storyteller figure was created in 1964 by Cochiti Pueblo potter Helen Cordero in memory of her grandfather, Santiago Quintana. She gathered her clay from a secret sacred place on the lands of her pueblo. Then she hand-coiled, hand painted and fired that first storyteller figure the traditional way: in the ground. Helen never used any molds or kilns to make her pottery.

Helen's creation immediately struck a chord throughout all the pueblos as the storyteller is a figure central to all their societies. Most tribes also have the figure of the Singing Maiden in their pantheon and in many cases, the mix of Singing Maiden and Storyteller has blurred some lines in the pottery world.

Today, as many as three hundred potters in thirteen pueblos have created storytellers. Their storytellers are not only men and women but also Santa’s, mudheads, koshares, bears, owls, eagles and other animals, sometimes encumbered with children numbering more than one hundred! Each potter has also customized their storyteller figures to more closely reflect the styles and dress of their own tribes, often even of their own clans.

Santiago Cordero Family Tree - Cochiti Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

Santiago Cordero was not a potter but he has the distinction of having been married to two of the most influential of Cochiti's potters: Lorenza Cordero and Damacia Cordero.

- Santiago Cordero (1876-) & Lorenza Cordero (c. 1874-)

- Juanita Cordero Arquero (c. 1906-)

- Mary Martin

- Bertha Martin Early (1964-)(former wife of Max Early of Laguna)

- Alan Early

- David Early

- Maria Rose Early

- Bertha Martin Early (1964-)(former wife of Max Early of Laguna)

- Mary Martin

- Felecita Eustace (1927-2016) & Ben Eustace (Zuni)(c. 1920s-)

- Christina Eustace

- James Eustace

- Joseph Eustace (c. 1950s-)

- Linda Eustace

- Nelson Eustace

- Helen Cordero (1915-1994) & Fred Cordero (d. 1994)

- George Cordero (1944-1990) & Kathy Cordero (Hispanic)

- Buffy Cordero (1969-) & Jerry Suina

- Jimmy Cordero & Mary Chalan

- Jimmy Cordero & Lenora Holmes (Hopi)

- Tim Cordero (1963- )

- Toni Suina (c. 1948-) & Delfino Trancosa (1951-)

- Leonard Trujillo (c. 1936-2017) & Mary Trujillo (1937-2021)

- Geraldine Trujillo

- Geraldine Trujillo

- George Cordero (1944-1990) & Kathy Cordero (Hispanic)

- Ramona Cordero

- Santiago Cordero (1876-) & Damacia Cordero (1905-1989)

- Josephine Arquero (1928-)

- Martha Arquero (1944-)

- Gloria Herrera

- Marie Laweka (1931-2002)

- Josephine Laweka (1960-2008)

- Dorothy Trujillo (Jemez/Laguna, married into Cochiti) (Damacia's niece, 1932-1999)

- Judith A. Suina (1960-)

- Cecilia V. Trujillo (1954-)

- Onofre Trujillo Jr. (c. 1969-)

- Norma A. Suina (1944-)