A Short History of Taos Pueblo

Taos Pueblo consists of two main structures, both of which are counted among the oldest continuously inhabited structures in the United States. The location straddles the Rio Pueblo de Taos (also known as Red Willow Creek), whose headwaters rise in the nearby Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The pueblo was designated a National Historic Landmark on October 9, 1960 and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1992.

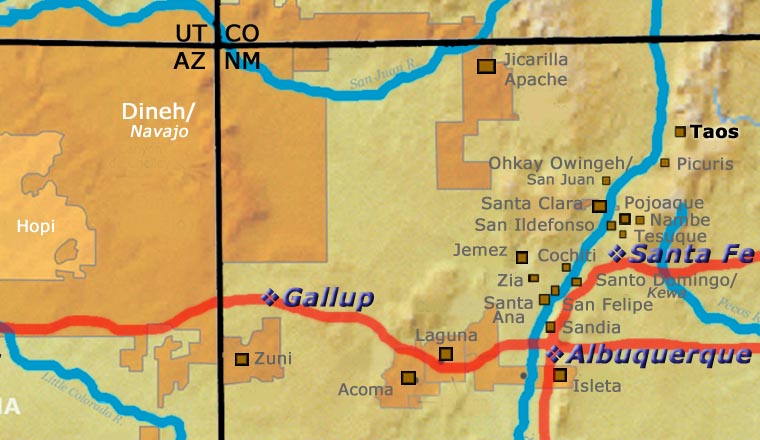

The Taos people first figure in the archaeological record about the same time Pot Creek Pueblo burned and was abandoned in the early 1300s. Some of the residents of Pot Creek split from the others and moved northeast to join with and merge into a small Tanoan pueblo located in a perfect spot with a great view. That became today's Taos Pueblo. The native tongue today at Taos Pueblo is Northern Tiwa, a member of the Tanoan family of languages. It is felt the tribe migrated to the area during the time of the Great Drought in the Four Corners region, the same drought that essentially forced nearly all the Pueblo peoples to migrate to the Rio Grande, Rio Puerco or Little Colorado River areas. The people of Taos, though, also feel that some of their people came from the north, which would include possible Jicarilla Apache migrants, and some from the far south, preferably from Aztec or Mesoamerican lands.

On the other hand, Taos was mostly peopled by 7 Jicarilla Apache clans and 6 Tewa clans, in addition to the one or two Tanoan clans left from before the immigrants arrived. For hundreds of years the semi-nomadic Jicarillas came and went from the forests and mountains around Taos, moving with the seasons. They established settlements in the Tusas Mountains and along the Upper Rio Grande. The economies and families of Taos and the Jicarillas were intertwined. Pottery and other trade goods from the region of Taos Pueblo have been found in Dismal River culture sites in eastern Colorado and across Kansas to the Black Hills of South Dakota. The pueblo served as a central contact point between the Rio Grande Pueblos to the south and the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Comanche, Apache and Ute to the north, northwest and northeast.

Around 1620 a Jesuit priest oversaw the construction of the first mission of San Geronimo de Taos. Friction between the tribe and the Spanish led to the killing of the resident priest and destruction of the church in 1660. Priests returned and rebuilt the church only to have the church destroyed again and two resident priests killed in the beginning hours of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

The Spanish were evicted from northern Nuevo Mexico in 1680 but returned in force in 1692. By 1700, a third mission church was being built at Taos Pueblo. For a few years the tribe and the Spanish got along, forced to be amicable in order to deal with their common enemies: the Ute and Comanche tribes. That pressure was relieved in 1776 when Governor Juan Bautista de Anza and his troops killed virtually the entire upper hierarchy of the Comanche tribe in the Battle of Cuerno Verde, near Greenhorn Mountain in southern Colorado.

In the 1700s an annual trade fair was established, promoted by the Spanish. The Spanish also established a slave market on Taos Plaza where captive Native Americans and black slaves were actively sold until Juneteenth Day in 1867. Taos Pueblo became a neutral zone where fighting and raiding were banned for the duration of the fair. The trade fairs continued after Mexico declared its independence in 1820, with a bit more tax and danger added (Mexico couldn't protect anyone from the regularly marauding Comanches, Apaches, Utes and Kiowas).

That's also when American fur trappers and traders first appeared in the area. The American military arrived in 1847, at the beginning of the Mexican-American War. Stephen Watts Kearny and his Army of the West had been waiting at Bents Old Fort on the Arkansas River in Colorado. As soon as the declaration of war happened, they flooded into New Mexico and took the territory without firing a shot. They replaced a few politicians, then they kept going. The American presence quickly led to the Taos Rebellion. The Taos Rebellion saw Governor Charles Bent and several other prominent Americans in the non-Indian village of Taos killed immediately. A few days later American troops and armed citizens arrived from Santa Fe and, thinking the rebels had taken refuge in the San Geronimo de Taos church, they bombarded the church, destroying it and killing many innocent women and children who were hiding inside. That effectively ended the rebellion. After a short trial, 17 of the surviving rebels were hanged from trees surrounding the plaza in the village of Taos.

A new mission church was constructed around 1850 near the west gate of the pueblo wall but the ruins of the old church are still visible today.

One result of the Taos Rebellion is that the tribe has never signed a peace treaty with the United States Government. That led to President Theodore Roosevelt using an Executive Proclamation to remove some 48,000 acres of the pueblo's mountain land and combine that with the fledgling Carson National Forest in 1906. That land was a point of major contention between the pueblo and Congress until it was returned to the tribe by President Richard M. Nixon in 1970. An additional 764 acres was returned to the tribe in 1996.

Today the community of Taos Pueblo is considered one of the most private, secretive and conservative of all the pueblos, even though the Pueblo of Taos offers more shops for visitors than any other pueblo. The North and South Houses of the pueblo are now a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Photo courtesy of Elisa Rolle, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About the Pottery of Taos Pueblo

The Taos area has been inhabited for a very long time. The Northern Tiwa who live there now migrated in from the west and north almost a thousand years ago. Archaeologists feel their first pueblo in the area was built at Pot Creek in the Ranchos de Taos area. They lived there maybe 300 years before the pueblo became uninhabitable. Around 1300 they had been joined by a group migrating north from the Santa Fe area. The potters of those folks were producing a variant of Mesa Verde-style pottery.

At that point, the tribe split up with some going southeast to build Picuris and others moving upstream a bit to build the Taos Pueblo we know today. Evidence found at Pot Creek Pueblo points to that happening around 1275 CE.

Taos potters figured out how to make micaceous pottery around 1450 and that has been their primary product ever since.

The arrival of the Spanish in force in 1598 was disastrous for Taos Pueblo. Like in every other pueblo, the yoke of the Spanish government and church ground the people down until they were ready for the revolt in 1680. Taos was also far enough off the beaten path that the ringleaders of the revolt gathered there and made their plans.

When the appointed day came, the warriors of Taos killed about 70 Spanish settlers and priests immediately. Then they went south to join with other Pueblo warriors to chase the Spanish out of New Mexico.

When Spanish troops returned to the area in 1696, the people of Taos made a deal that saved them from further bloodshed.

In 1723 the Spanish government limited all trade with the Plains tribes to Taos and Pecos Pueblos. That's when the great annual summer trading fairs began. The Comanche and Kiowa came to trade captives and furs for horses, grain and trade goods from Chihuahua. That was also the beginning of a slave market in Taos that didn't end until Juneteenth Day in 1867.

In 1847 the Mexican-American War broke out and all of New Mexico was taken by Stephen Watts Kearny and his Army of the West without firing a shot. However, many folks at Taos and Taos Pueblo didn't want to submit to the American yoke either, so they rebelled and killed Charles Bent, the newly appointed governor, and a few other American officials and sympathizers.

The American response to that left many women and children dead when the church they were hiding in at Taos Pueblo was blown up. The rebel ringleaders were immediately caught, tried and executed. Technically, Taos Pueblo is still at war with the United States.

These events almost destroyed the culture and traditions of the pueblo. As for the making of pottery, production was down to the barest of utilitarian and ceremonial wares. Micaceous pottery as artwork had to wait until the 1990s for recognition while the first utilitarian micaceous pieces appeared in the Taos area more than 500 years ago. Many cooks native to northern New Mexico still say their micaceous bean pot is the best pot they'll ever cook in.

Today, virtually all Taos Pueblo pottery has a slip of micaceous clay added before it's fired. Some potters make entire pieces of micaceous clay. The mica adds structural strength to the clay and their pottery can be made with very thin walls.

Most contemporary Taos pottery gets its appeal from the thin walls, the light construction and the basic shapes. Because it's rather hard to add other decorations to a micaceous piece, most Taos pottery is plain except for that glistening slip.

Our Info Resources

Some of the above info is drawn from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Some has been gleaned from Duane Anderson's All That Glitters: The Emergence of Native American Micaceous Art Pottery in Northern New Mexico, School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1999.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.