A Short History of Cochiti Pueblo

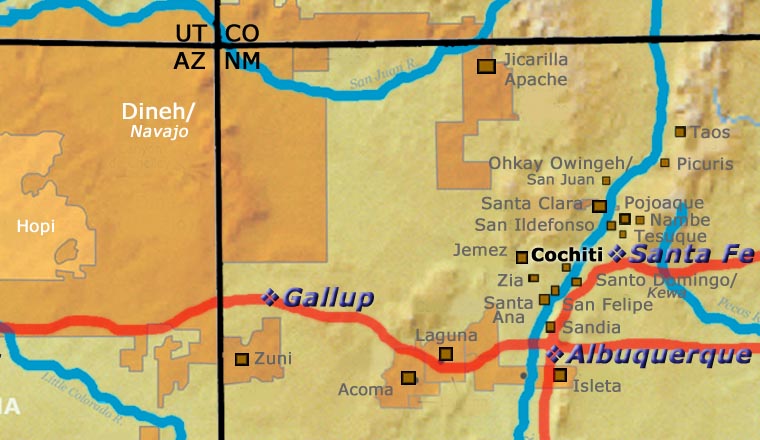

Cochiti Pueblo lies fifteen miles south of Santa Fe along the west bank of the Rio Grande. What is now Bandelier National Monument is the pueblo's most recent ancestral home. They may have relocated to the Bandelier area from the Four Corners region around 1300, and then closer to the Rio Grande in the 1400s in the heart of an even worse drought situation. They merged with people who had been living in the area for hundreds of years before, pushing south until they came up against the countryside of the Tiwa pueblos in the middle Rio Grande.

In those days, the people of Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe were one Keres-speaking culture. They split into three cultures when some decided to go further down the Rio Grande to settle (San Felipe), and some decided to cross to the eastern side (Santo Domingo). All three speak dialects of Eastern Keres and are considered very conservative.

Cochiti legend says that Clay Old Woman and Clay Old Man came to visit the Cochitis. While all the people watched, Clay Old Woman shaped a pot. Clay Old Man danced too close and kicked the pot. He rolled the clay from the broken pot into a ball, gave a piece to all the women in the village and told them never to forget to make pottery.

Most outsiders who visit Cochiti Pueblo these days do so on the way to or from either the recreation area on Cochiti Lake or Kasha-Katuwe Tent Rocks National Monument.

For more info:

Cochiti Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Cochiti official website

About the Pottery of Cochiti Pueblo

In proto-historic times, human effigy pots, animals, duck canteens and bird shaped pitchers with beaks as spouts were common productions of the Cochiti potters. Many of these were condemned as idols and destroyed by the Spanish priests. The people almost entirely stopped making them. That interference stopped when the Spanish finally left for good in 1820 but the fantastic array of figurines created by Cochiti potters remained essentially dormant until the railroad arrived in the early 1880s. Then Cochiti potters were among the first to enter the tourist market and they produced many whimsical figures into the early 1900s. Then production followed the market into more conventional shapes.

In 1885, a delegation of Cochiti men got on the train and went to Washington DC. They met the President and spoke to Congress. Then they got back on the train and went to New York City. There they attended a circus performance, went to the opera and the Bronx Zoo, and were taken to enjoy other highlights of the cultural scene of the day. Then they went back to Cochiti. No one took any notes or made any drawings: that idea was alien to them. When they returned home they talked and talked and talked. As the stories spread around the village, elements in them grew and deformed. Today, an astute observer will find angels, nativities, cowboys, tourist caricatures, snakes, dinosaurs, turtles, goats, two-headed opera singers, clowns, tattooed strongmen, tattooed circus ringmasters, Moorish nuns in their habits, Conquistadors in leather and even mermaids in the Cochiti pottery pantheon, most produced only since the early 1960s and based on characters described in Cochiti's oral history.

A few modern potters make traditional styled pots with black and red flowers, animals, clouds, lightning and geometric designs but most Cochiti pottery artists now create figurines. Most notable is the storyteller: a grandfather or grandmother figure with "babies" perched on it. Helen Cordero is credited with creating the first storyteller in 1964 to honor her grandfather. The storyteller style was quickly picked up by other pueblos and each modified the form to match their local situation (ie: clay colors and tribal and religious traditions). In some pueblos, potters produce various animal storytellers and nativities.

Today, Cochiti potters face the challenge of acquiring the clay for the white slip. Construction of Cochiti Dam in the 1960s destroyed their primary source of their trademark white slip and gray clay. Now the white slip comes from one dwindling source at Santo Domingo, Cochiti Pueblo's neighbor to the south.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.