Acoma

A Short History of Acoma Pueblo

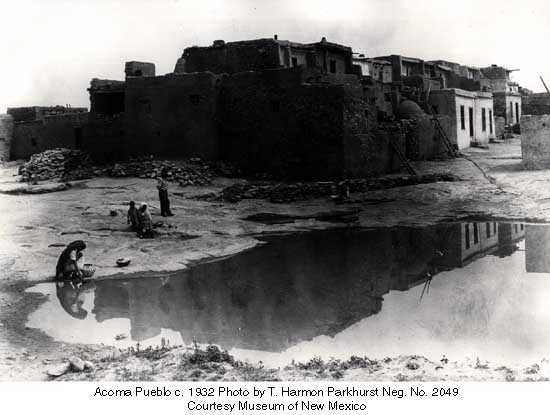

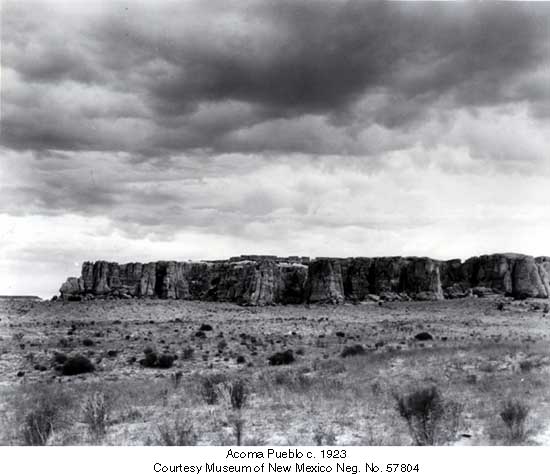

According to Acoma oral history, the sacred twins led their ancestors to "Ako." Ako turned out to be a magical mesa composed mostly of white rock. There the sacred twins instructed the ancestors to make that mesa their home. Acoma Pueblo is called "Sky City" because of its position atop the high mesa.

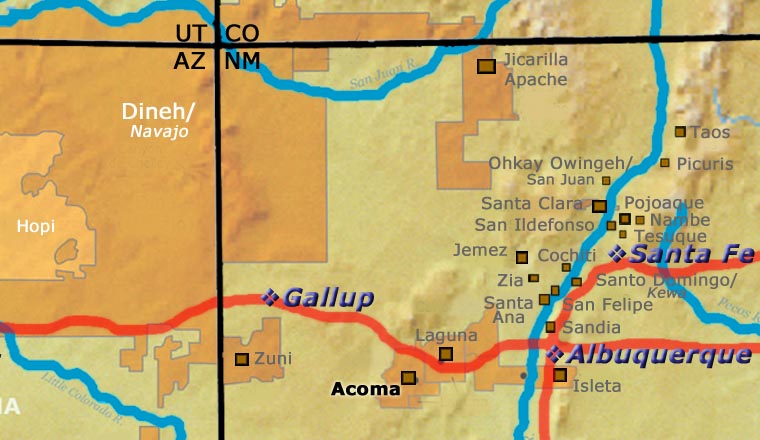

Acoma, Old Oraibi (at Hopi) and Taos all lay claim to being the oldest continuously inhabited community in the U.S. Those competing claims are hard to settle as each village can point to archaeological remnants close by to substantiate each village's claim. Acoma is located about 60 miles west of Albuquerque in a landscape littered with the ruins of ancient pueblos, many more than 1,000 years old.

The people of Acoma have an oral tradition that says they've been living in the same area for more than 2,000 years. Archaeologists feel more that the present pueblo was established near the end of the major migrations in the 1200 and 1300s. The location is essentially on the boundary between the Mogollon (Mimbres), Hohokam (Salado) and Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloan) cultures. Each of those cultures has had an impact on the styles and designs of Acoma pottery, especially since modern potters have been getting the inspiration for many of their designs from pot shards they have found while walking on pueblo lands.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado ascended the cliff to visit Acoma in 1540. He afterward wrote that he "repented having gone up to the place." But the Spanish came back later and kept coming back.

Around 1598 relations between the Spanish and the Acomas took a nasty turn with the arrival of Don Juan de Oñaté and the soldiers, settlers and Franciscan monks that accompanied him. After making the arduous ascent to the mesa top, de Oñaté decided to force the Acomas to swear loyalty to the King of Spain and to the Pope. When the Acomas realized what the Spanish meant by that, a group of Acoma warriors attacked a group of Spanish soldiers and killed 11 of them, including one of de Oñaté's nephews.

De Oñaté retaliated by attacking the pueblo. His troops burned most of it and killed more than 600 people. Another 500 people were imprisoned by the Spanish. Males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sold into slavery. 24 men over the age of 25 had their right foot amputated. Many of the women over the age of 12 were also forced into slavery. Most were parceled out among Catholic convents in Mexico City.

Two Hopi men were also captured at Acoma. The Spanish cut one hand off of each and sent them home to spread the word about Spain's resolve to subjugate the inhabitants of Nuevo Mexico. Spanish monks did make the trip a few years later but Spanish military made hardly an appearance in Hopiland.

When word of the massacre (and the punishments meted out after) got back to King Philip in Spain, he banished Don Juan de Oñaté from Nuevo Mexico. Some Acomas had escaped that fateful Spanish attack and returned to the mesa top in 1599 to begin rebuilding.

In 1620 a Royal Decree was issued which established civil offices in each pueblo and Acoma got its first governor. That didn't help the people any as those appointed to the government positions were also those most on the take with the Spanish authorities. By 1680, the situation between all of the pueblos and the Spanish had deteriorated to the point where the Acomas were extremely willing participants in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt.

After the successful Pueblo Revolt pushed the Spanish back to Mexico, refugees from other pueblos began to arrive at Acoma. Most feared the eventual Spanish return and probable reprisals. That strained the resources of Acoma badly. Then the Spanish returned in force and residents of the pueblo had to make a hard decision. Many of the refugees chose to try a peaceful solution: they relocated north to the ancient Laguna area and made peace with the Spanish as soon as they reappeared in the region. Acoma held out against the Spanish for awhile but soon capitulated.

Over the next 200 years, Acoma suffered from breakouts of smallpox and other European diseases to which they had no immunity. At times they would side with the Spanish against nomadic raiders from the Ute, Apache and Comanche tribes. Eventually New Mexico changed hands. Then the railroads arrived and Acoma became dependent on goods made in the outside world.

For many years the villagers were content on the mesa. Now most live in villages on the valley floor where water, electricity and other necessities are easily available. A few families still make their permanent home on the mesa top. The old pueblo is used almost exclusively these days for ceremonial celebrations.

For more info:

Acoma Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Acoma official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, © 2001

Acoma & Laguna Pottery, Rick Dillingham with Melinda Elliott, ISBN 0-933452-32-2, School of American Research Press, © 1992

Upper photo courtesy of Marshall Henrie, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About the Pottery of Acoma Pueblo

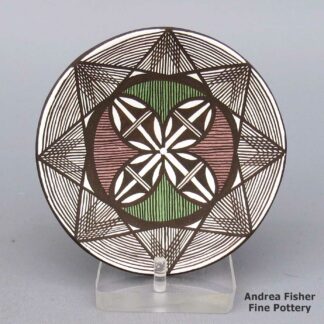

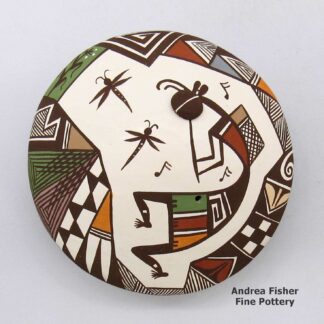

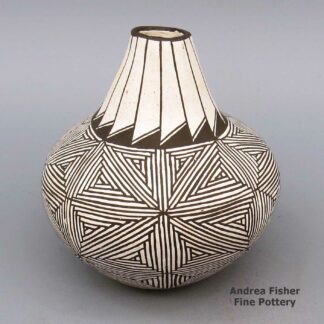

Acoma's dense, slate-like clay, allows the pottery to be thin, lightweight and durable. After a piece is formed, it is usually given several coats of white clay slip. Once that dries, black and red design motifs are added using mineral and plant derived paints. Fine lines, geometrics, parrots and old Mimbres-culture designs are commonly seen motifs. The traditional paintbrush for Acoma potters is made by chewing the leaves of the yucca plant. Because the clay is so thin and dense, very little carving is done. Most designs are painted, some added with sgraffito (etching) and some are made of appliqués. There are also some potters who make “corrugated” surfaces using a stick or other tool to deform the surface of their pieces in a regular pattern.

Acoma potters tend to use a large variety of Mimbres-Revival designs. These are based on things they have seen on ancient pot sherds that litter the ground around Acoma Pueblo. Those pot sherds are testimony to hundreds of years of pottery being made and broken in the area. Today’s potters also like to paint birds, fish, animals, dancers, flowers and some elements common to Zuni and Hopi designs.

Historically, Acoma has been known for large, thin-walled "ollas," jars used for storing food and water. With the arrival of the railroad and tourists in the 1880s, Acoma potters adapted the size, shapes and styles of their pots in order to appeal to the new market.

Acoma Pueblo is home to noted potters of the Lewis and Chino families, as well as many others. Acoma potters felt it was an inappropriate display of ego to put their signature on a pot up into the mid-1960s. The 1960s was also a time when the primary white clay vein mined by the Acomas passed through a layer of widely distributed impurities. Those impurities passed through the pottery making process and appeared only in the firing. Or worse yet, sometimes well after firing. The clay problem was so bad it affected virtually every potter in the pueblo and every pot they made. So many pots spalled that even the best potters sold them anyway, often signed. Thankfully, by the late 1960s they had dug through that layer of clay and into a deeper layer that didn't have the problem.

Today’s Acoma potters make jars, plates, bowls, cups, seed pots, wedding vases, storytellers, nativities, miniatures, figures and more. Their color palette tends to be red, orange and black on a white base. As designs are becoming more contemporary, other natural colors are being added to the palette. Acoma Pueblo pottery shapes and forms are also evolving with the market and with individual potters stretching the bounds of their craft.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.

Showing 1–12 of 156 results

-

Aggie Henderson, jhac3b021, Storyteller with five children

$175.00 Add to cart -

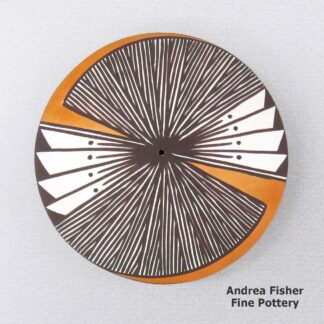

Alisha Sanchez, zzac2m080m1, Polychrome plate with geometric design

$175.00 Add to cart -

Amanda Lucario, zzac3b132m1, Seed pot with a geometric design

$195.00 Add to cart -

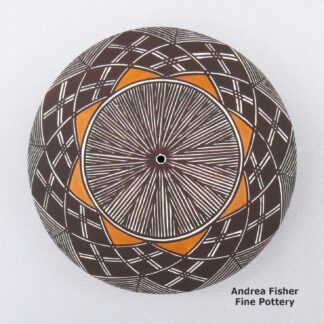

Amanda Lucario, zzac3b132m2, Seed pot with a geometric design

$195.00 Add to cart -

Amanda Lucario, zzac3b132m3, Seed pot with a geometric design

$195.00 Add to cart -

Amanda Lucario, zzac3b133, Seed pot with a geometric design

$110.00 Add to cart -

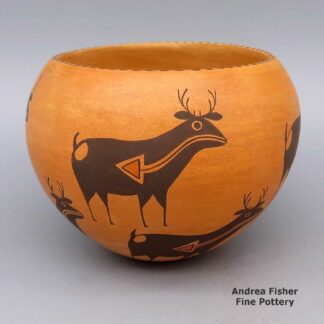

Anne Lewis, zzac2l220: Polychrome bowl with Mimbres and geometric design

$725.00 Add to cart -

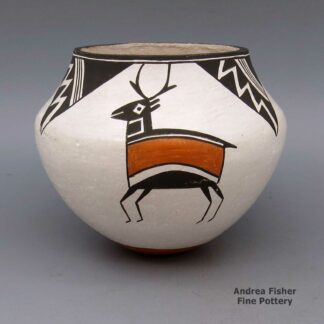

Carmel Lewis, lkac2l323, Black-and-red bowl with deer-with-heart-line design

$325.00 Add to cart -

Carolyn Concho, lkac2l295: Miniature polychrome jar with applique and painted lizard, ladybug, and geometric design

$135.00 Add to cart -

Carolyn Concho, zzac2m084m8, Polychrome seed pot with applique and geometric design

$225.00 Add to cart -

Carrie Chino Charlie, paac2l303: Black-on-white jar with geometric design

$275.00 Add to cart -

Carrie Chino Charlie, paac2l305: Black-on-white seed pot with geometric design

$195.00 Add to cart

Showing 1–12 of 156 results