Hopi

About the Hopi People

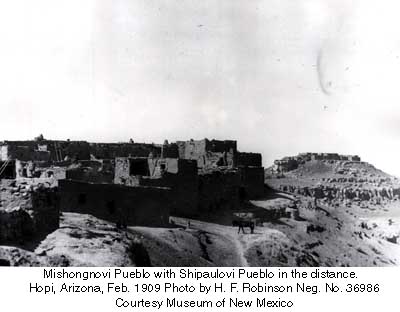

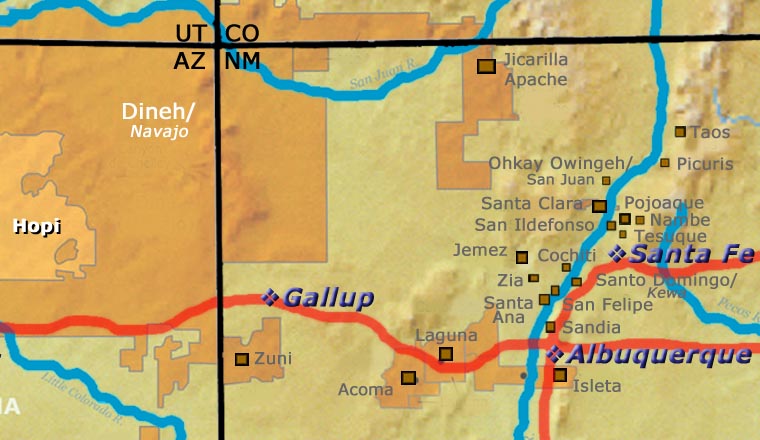

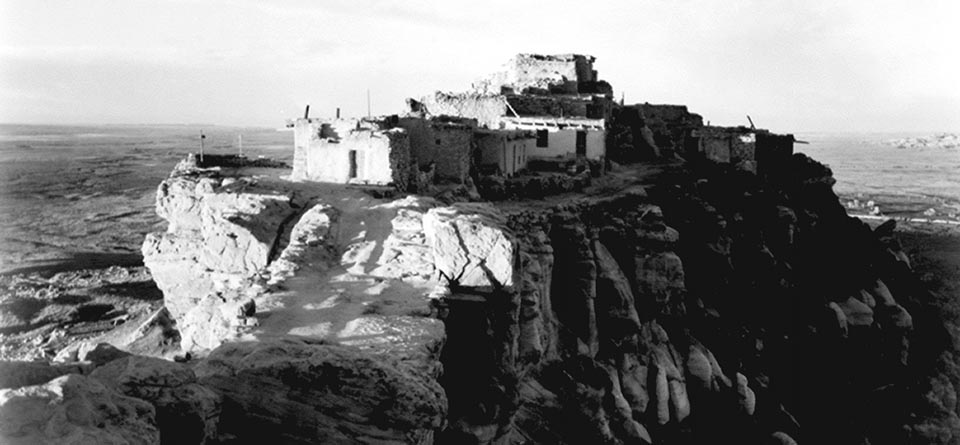

The Hopi people live in villages on or around three primary mesas in northeast Arizona. Some of their communities have been continuously occupied since the 12th century. In Hopi religion, the Hopi mesas are "the Middle Place," that place between heaven and hell that is best for them to live in. Their oral histories say they spent thousands of years migrating across the continents to find this place and make it their home. The Hopi culture has been built up through welcoming incoming migrants who brought elements of value to the Hopi mesas. "Elements of value" usually pertains to new technology or ritual. A new clan coming with a new means of influencing the elements of the Earth to deliver more rain and a more bountiful harvest were welcome, but were usually tested before being allowed to settle in a settled community. Ritual specialists and their paraphernalia always had a value but some had more value, especially if they came from the far south. New pottery, agriculture or irrigation technology was also usually welcome, once adapted to the local environment and proven to be better.

Because they lived isolated in a formidable, arid countryside, with a strict fundamentalist religion ruling them longer than any other pueblo group, today's Hopis have retained much of their religion, lifestyle and language from before the Spanish arrival. That said, the Hopi mesas have also long been sanctuaries for other tribes and cultures during times of great drought or great hardship (such as those brought on by the Spanish in the early years of their colonization of New Mexico). As a result, the landscape around the Hopi mesas is littered with the remains of villages once founded by people speaking Keres, Towa, Tewa, Tiwa and other Uto-Aztecan languages.

The Hopi pottery tradition is quite varied with roots traced as far away as vitrified ceramics found in the environs of Valdivia, Ecuador, and produced between 1500 and 2500 BCE. Archaeologists excavating in the ruins around First Mesa found sherds of pottery styles and painted and incised designs also found in the Rio Salado region and among the ancient Sinagua and Kayenta settlements in the Wupatki, Tuzigoot, Walnut Canyon and Homol'ovi areas (all abandoned between about 950 and 1400 CE).

The area around Jeddito was occupied by Towa- and Keres-speaking people beginning around 1275. The Jeddito area is where Jeddito yellow is found, the clay that later made the pottery of Sikyátki so spectacular.

Beginning in the 1200s, Towa- and Keres-speaking people began to build what became Awatovi, at the foot of Antelope Mesa, east of Walpi and south of Keams Canyon. Sikyátki itself was also built by people incoming migrants, beginning in the early 1300s. At first Sikyátki was inhabited solely by the Kokop (Firewood) clan (a Towa-speaking group), then the Coyote clan came and grew to become the largest single clan in the village. In the mid-1400s CE a group of migrants arrived from the area of Pottery Mound (in central New Mexico). They brought with them new rituals, ritual paraphernalia and iconography. They built new kivas and painted incredible murals on some of the walls. Many of those designs made their way onto pottery. Over the next 150 years, the potters of Sikyátki developed the design palette further. Their pottery was traded far and wide across the Southwest. Then Hopi oral history says that one day, Sikyátki's religious chief decided they had strayed too far from their religious roots. Deciding there was no way to bring them back to the straight-and-narrow, he went to the chief of Walpi and arranged to have it all ended. The chief of Walpi made preparations, then one morning while the men of Sikyátki were in their kivas, men from other pueblos attacked.

It is said that Sikyátki and most of its people were wiped out in a few hours, but most of the clans that populated the village have somehow continued to exist. Why the village was destroyed as it was is shadowed in myth but Jesse Walter Fewkes (the first archaeologist to excavate in the Sikyátki area) felt it happened before the first Spanish visitor arrived in 1540. Modern archaeological dating techniques have set the destruction of Sikyátki at about 1625 CE, just a few years before the Franciscan priests arrived at Awatovi to build a mission.

The ruins at Awatovi (on Antelope Mesa,) have yielded pottery sherds in styles and with designs that were also prominent in the prehistoric village now known as Pottery Mound (on the banks of the Rio Puerco in central New Mexico). Among the pot sherds found at Pottery Mound are plain and decorated Hopi products, white clay products from the Acoma-Zuni area and red clay products from north-central New Mexico. Pottery Mound was abandoned around 1450 CE, about 90 years before the Spanish arrived in force.

When Pedro de Tovar first came to the Hopi mesas, the Hopi thought he was the fulfillment of a prophecy wherein a long lost white brother, Pahana, would return to them. However, the Hopi were expecting de Tovar to respond with honor to the "Nachwach-clan" handshake when the chief of Walpi offered it to him. All de Tovar knew to do when offered the open, upraised hand of friendship and brotherhood was to drop a gold coin in the open palm... Instantly the Hopi knew these white men were not any of the prophesied ones.

It has been reported that many of the residents of Awatovi were not as resistant as the other Hopi villages were to the Christianizing practices of the Spanish Franciscan monks when they came into the Hopi lands around 1629. Awatovi was the only pueblo in the Hopi region to construct a substantial Christian mission, San Bernardo de Aguatubi. Most archaeologists attribute that to the reason why residents of Walpi, Mishongnovi and other, smaller pueblos destroyed the village and killed nearly all its residents in the winter of 1700-1701. The hated Spanish priests had returned to Awatovi a few years before and were again beginning to exhort the Hopi people to be baptized and become Christians.

Oral history has it that the religious chief of Awatovi had also approached the elders of Walpi and other pueblos because his people had strayed too far. He also made a deal to destroy the village and kill all the residents, including himself. At the time of destruction, Awatovi was the largest and most populous pueblo in the Hopi mesas. After the killing was finished, they burned the pueblo and salted the ground so it would never be occupied again.

Around 1690 the people of Walpi relocated themselves from their old pueblo at the foot of First Mesa to a new location atop the southernmost finger of First Mesa, a move made for defensive reasons. In making that move, they also invited several of the smaller pueblos around them to join them in making that move and becoming one village at the top of the mesa.

Southern Tewa warriors and their families (mostly from the Santa Fe River Basin area) began arriving in the area in 1696 and were steered to take up residence at the foot of First Mesa along the only route to the mesa top (in that location, the Tewas would be the first people to encounter incoming Spanish military - the people of Walpi felt they would make a good first line of defense should the Spanish attempt to reconquer them). The Tewas were also good at repulsing Ute, Paiute and Diné raiders.

After they won a decisive battle with Ute raiders, they were allowed to build Tewa Village (also known as Hano) at the gap between the rocks on the trail up First Mesa. Some of the Tewa women were potters and in the ages-old way, they slowly shared what they knew with Walpi potters, and vice versa. That cross-pollination went on for years, and not just with pottery. Cross-cultural marriages happened, too, and today the people are known as Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Tewa, depending on their ancestry. And while Tewa Village is completely surrounded by the Hopi Reservation, many of the residents are fluent in Tewa, Hopi and English. Some are fluent in Spanish and Dieh, too. There is a tribal injunction against any Hopi speaking Tewa: they may understand what is being spoken in Tewa but they are not allowed to speak Tewa themselves.

During those same troubled times Towa-speaking people from the Jemez Mountains area migrated to Hopi and Diné territory (in the Jeddito Wash area) to escape the violence of the Spanish reconquest. They established familial ties that are still in place today.

The village of Sichomovi on First Mesa was founded in the early 1600s by members of the Wild Mustard Clan, Roadrunner Clan and others who'd come to the area from east of Santa Fe (Pecos Pueblo and smaller pueblos in the Galisteo Basin) via Zuni. They seem to have stopped at Zuni for a few years and assimilated somewhat. When they moved on to Hopi, there were quite a few Zunis among them, that's why the people of Walpi (and some from Zuni) refer to Sichomovi as a Zuni pueblo.

Another group of Tewas arrived at Hopi around 1600 CE and became known as the Asa clan. They had traveled from the Abiquiu area through Santo Domingo, Acoma, Laguna and Zuni, picking up and dropping off people, technology and social practices along the way. Some settled at Awatovi while others continued to Coyote Spring (under the gap at First Mesa). They built a new pueblo where Hano now stands (it was known as Hano back then, too). A few years later drought, disease and arguments with the people of Walpi caused them to relocate again.

They went east to the Diné settlements around Canyon de Chelly and most stayed there several decades before drought, disease and argument with the Diné caused some to either return to First Mesa or travel east to the Jemez Mountains. The descendants of those who intermarried with the Diné stayed with the Diné and are now a numerous clan known as Kinaani (High-standing house).

Those who returned to First Mesa found Hano occupied by the newly arrived Southern Tewa. The Asa were given a strip of land on the east edge of the mesa to build on but soon after, many of them moved to Sichomovi and merged with clans there.

Around 1800 a period of severe drought caused many Hopis to migrate to Zuni territory and once the drought had broken, most returned to their ancestral lands. While at Zuni many Hopi potters picked up the Zuni method of white-slipping their pottery and continued to produce white ware after returning to Hopi. However, their quality wasn't nearly as good as that of Hopi pottery produced before the Spanish invasion.

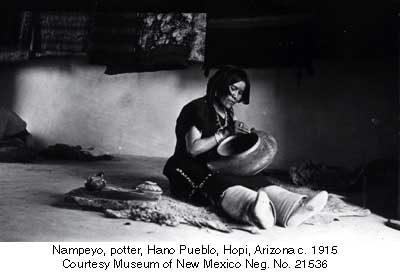

By the mid-1800s the Hopi pottery tradition had been almost completely abandoned, its utilitarian purposes being taken over by cheap enamelware brought in by Anglo traders. Hopi pottery production sputtered along until the late 1880s when one woman, Nampeyo of Hano, almost single-handedly revived it. Nampeyo lived in Hano on First Mesa and was inspired by pot sherds she found among the nearby ruins of the ancient village of Sikyátki. She also studied designs painted on pottery from other areas around the Hopi mesas. Today credit is given to Nampeyo for fully reviving the Sikyátki style but "Sikyátki style" has been broadened to include almost any designs that were painted in the Four Corners area between about 600 and 1750. Nampeyo was so good that Jesse Walter Fewkes, the first archaeologist to formally excavate Sikyátki, was concerned that her creations would shortly become confused with those made hundreds of years previously. In truth, from about 1885 to 1906, there were so many buyers of Hopi pottery that virtually every Hopi potter was working to produce similar pottery to satisfy that market. Then in 1906, Congress passed the Antiquities Act and that ended the wholesale collection of (real and fake) ancient pottery. From that point on, every piece of pottery had to have a modern provenance.

The late 1800s also saw the Bureau of Indian Affairs working hard to remove Hopi children from their families and force them into the white man's schools, teach them the white man ways and assimilate them into white society. The first school used a couple extra rooms at the Keams Canyon Trading Post and as much as some Hopi were interested in sending their children there, the folks of Oraibi protested at sending their children 35 miles away for most of the year. A few years later the BIA built the Oraibi Day School at Oraibi but still, the conservative (Hostile) Hopis of Oraibi refused to send their kids.

In 1894 a group of Hopi parents officially announced they would not send their children to any government schools and allow them to be exposed to the white man's culture. The federal government immediately sent in troops and 19 Hopi men were rounded up and transported to the military prison on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay. They were kept at Alcatraz for almost a year, then were allowed to return home after signing an agreement to not cause any trouble with the Friendly Hopis of Oraibi, to construct new homes for their families, to send their children to government schools until the children either finished their schooling or turned 20 years old, to allow Christian missionaries to build churches on Hopi land and to inform on and help to apprehend any Hopi who broke any clause in the agreement. Eventually the conflict between conservatives and moderates caused what is now known as the "Oraibi Split" in 1906.

Smallpox paid a visit to the Hopi mesas in 1898. The epidemic was severe on First and Second Mesas but it never got to Third Mesa: a line of Indian police (composed of Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Diné men) stationed all along the length of the canyon between Second and Third Mesas helped with that. 632 people caught the disease (a bit over half the population) and 187 died. It was over by April, 1899. As part of the clean-up after, the government thought about destroying all the food stored in granaries and such in each pueblo, but they found several years worth of food stored away. They didn't destroy any of it. But they did go about forcibly vaccinating people on First and Second Mesa, immediately. Soldiers and Indian police invaded each village before sunrise and went into each home to bring everyone out into the central plaza. There, essentially at gunpoint, each was vaccinated. Some men objected and were vaccinated and got a hair cut for their efforts (to the Hopi, cutting a man's hair was like taking his manhood). Some men snuck away and were found in a house on the edge of the village. When they refused to come out, soldiers started to break the house down around them. The Hopi were unarmed so the "gentleman" soldiers put down their weapons and a brawl ensued. Once it was over and the Hopis subdued, several of their leaders were segregated and ended up incarcerated for several months.

Note: In the winter of 1901-1902, cutting Indian men's hair became an official policy of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Indian Agents and Superintendents all over the country had a heyday with it. Superintendent Charles Burton proceeded to cut the hair of every Hopi man on the reservation. He is still cursed by the people for it.

After this, Burton decided to send Indian police into the villages specifically to kidnap children and transport them to the boarding school at Keams Canyon. His methods aggravated an already bad situation. This was a time when the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad, in tandem with Fred Harvey Tours, was flooding the Hopi Reservation with tourists. The tourists didn't like what they were seeing and were very vocal about it. At one point, Burton tried to get the reservation segregated to keep tourists and "scientists" out. He was dead set on fully assimilating the Hopi into American society on his watch. In a few months the school went from 17 students to 114. A principal and two teachers with two classrooms. And the principal was observed breaking sticks on the back of a Hopi boy he was punishing... One teacher who went to the Oraibi Day School lasted five weeks before resigning: she couldn't stomach the abuses being heaped on the children. But this was official Bureau of Indian Affairs policy at the time.

Note: The terms Hostile and Friendly are terms given two factions by government agents and missionaries. It was hard to discern one from the other until the Oraibi Split, and by that time, a group of Hostiles were active on Second Mesa at Shungopavi. Some reports say the Hostile leaders were more friendly to outsiders than the Friendly leaders were, even though it was the presence of outsiders that was causing the problems. The Friendly leaders did have a way of saying what the government wanted to hear, and then not following through, whereas the Hostile leaders made no promises they might have to break.

In 1909, Tewaquaptewa (a Friendly chief deposed by the government and incarcerated at the Riverside Indian Boarding School in California for 3 years) returned to Oraibi and continued agitating for the Hostiles to be expelled from Oraibi. Before it got too crazy, the leaders of the Hostiles in Oraibi chose to move and build Bacavi, a new village above Bacavi Springs, about a mile from Hotevilla.

Until 1934, the Indian Agents and missionaries who were assigned to Hopi did everything in their power to "civilize" and "Christianize" the Hopi but, as one aggressive missionary wrote, "The priests were not very anxious to furnish me anything that I wanted to use to undermine their religion." The government didn't send any more Hopi to federal prisons after 1895, it was felt that exiling them to a church-run government boarding school was better: the conditions of confinement were the same but the prisons didn't force Christianity on them.

From 1882 to 1996 there were also constant problems with Diné encroachments on Hopi land. The disputes were dealt with by Congress, then by the courts, then back to Congress... This was a real problem between the tribes but in reality, it was aggravated by outside forces, their lawyers and their PR firms as a means of getting access to the vast natural resources beneath both the Hopi Reservation and the Diné Nation.

Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act in 1935. This forced elections on every reservation and forced the creation of a Hopi Tribal Council, meant to replace a working system of government that had been in effect for more than 1,000 years before the Declaration of Independence. Many Hopis were offended and refused to vote. 37 percent of eligible Hopi voters did turn out for that and it passed by a very slim margin. Then Congress passed the Mineral Development Act in 1938. That provided that "lands within an Indian reservation may, with the approval of the Secretary of the Interior, be leased for mining purposes, by authority of the Tribal Council or other authorized spokesmen for the Indians". The first Hopi Tribal Council lasted from 1938 to 1943, then disbanded. The tribe was coerced to put together a new Tribal Council in 1951.

The 1930s were also a time of Dust Bowl conditions in northern Arizona. The Department of the Interior designated 19 grazing districts throughout the Hopi and Navajo Reservations. Grazing District 6 was created in 1943, designating about 650,000 acres surrounding the Hopi mesas and within the bounds of the 1882 Executive Order Area to be for Hopi use exclusively. Effectively, that reduced the Hopi Reservation to only Grazing District 6 and the rest of the Executive Order Area became the Joint Use Area: 1.8 million acres occupied by members of both tribes. Joint ownership of the surface estate frustrated the negotiation of drilling and mining leases for years.

In 1974 the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act authorized partition of the Joint Use Area and prospecting leases were signed within a year. Fences went up, the open range was divided, access to sacred sites was blocked and many Diné people had their lives disrupted. Soon, the federal government initiated a program to relocate about 100 Hopi people and between 10,000 and 13,000 Diné people out of the Joint Use Area. Instead of evicting the people at gunpoint, it was made illegal for anyone within the area to build or repair a home, corrals or any other structures. There was also an active Diné livestock reduction program in effect. A staff attorney of the Big Mountain Legal Office, Lee Brooke Phillips, said in an interview for New Voice Radio in April 1988, "The reality is that people are really faced with a surrender-or-starve situation."

Many of the Dineh people were relocated to newly-built government housing in Tuba City but that wasn't enough to accommodate everyone. 400,000 acres of "New Lands" were designated for the remaining people, 360,000 acres of that in the Rio Puerco Basin. However, an accident in 1979 at a uranium mine upstream along the Rio Puerco spilled 94 million gallons of radioactive water and 1,100 tons of toxic solid waste into the Rio Puerco, killing livestock for miles downstream and contaminating the whole area.

In 1996 another Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute Settlement Act was signed by President Bill Clinton. The Act was necessary to clear up some vague language in the 1974 Act. The 1996 Act also laid the basis for the Hopi to acquire up to 250,000 acres of "New Lands." However, that requires positive action from the State of Arizona and that has not been forthcoming.

"The United States’ interests and the interests of the Hopi Tribe are not necessarily coextensive." - from a brief filed in Federal Court in 2001 seeking to resolve problems with Diné who refused to leave their homes on Hopi land and refused to lease the land from the Hopi (the 1996 Act offered Diné still living on Hopi land in the Joint Use Area the right to negotiate a 75-year lease with the Hopi Tribal Council). The land dispute ground on for several more years. Shortly after the Hopi chairman who initiated the original legal proceeding died, the Federal judge ruled on the case. Essentially, the Hopi got all of Grazing Section 6 while they lost everything outside of Grazing Section 6.

Other Resources:

About the Pottery of the Hopi People

Pottery was being made in the area of the Hopi mesas before migrants from the central Mexico area first arrived in the 600s CE. Those migrants, though, they brought a much better ceramic technology with them. They also brought a whole new design vocabulary, architectural advancements, more defined rituals and better seeds with other agricultural advancements. They spread out across the Southwest between the Virgin River and the Rio Grande, from the Chihuahua and Sonora deserts north to the Great Salt Lake, and they multiplied. The weather of this new countryside was very fickle, though, and they had to learn how to store food and keep it good for years. The best tool for that was pottery. Then they learned to decorate their pottery with their prayers for the seed within, and for the survival of their people.

For hundreds of years those designs were repetitive geometrics, in black-on-white or gray-white bisques, most matte but more and more polished as time went on. Then, from the south again, figures in black-on-white were introduced. Then came figures and designs in red-and-black-on-white. Then came figures and designs in various combinations of red, black and white on various backgrounds. Each step in the development of decorative and color schemes is reflective of experiential religious developments within one clan or another, one pueblo or another. While a lot of what flowered into Sikyátki style and design was developed in bits and pieces along the rim of Antelope Mesa, it took the experience of Sikyátki to put it all together. Just as the design palette of Sikyátki reached its peak, the village's chief determined they had strayed too far from the traditionally conservative Hopi path and they needed to be put to death for it. He arranged with the elders of Walpi and other villages to have the deed done and sometime in 1625 it was completed: everyone was killed except for a few ritual specialists saved for their spiritual value.

The styles and designs of Sikyátki lived on on some Awatovi pottery for a few years but the entire design palette changed after the Spanish arrived in 1629. San Bernardo Polychrome came into production almost immediately with the reduction in labor force as so many of the Awatovis were forced to build a mission first, then serve it thereafter. The design palette changed, too, when all the kachina designs were forced out by the Franciscan priests. Almost everything changed again with the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. There was a general return to themes prevalent before the Spanish arrived across the entire Southwest, except by then most potters were firing their pots using sheep, cow or horse manure. Around the Hopi mesas, a merging of designs and supernaturals with the layouts from the San Bernardo and Sikyatki pahses happened. Some archaeologists have termed the pottery that was produced for 100 years after the Pueblo Revolt as "Payupki phase." It faded out around 1780, about the same time the last of the Tiwas and Keresans returned to the Rio Grande Valley from the village of Payupki on Second Mesa. After that came the phases of Polacca Polychrome, including the white-slipped years after the times of drought and disease in the 1800s that were spent at Zuni.

By the mid-1800s, Hopi pottery tradition had been almost completely abandoned, its utilitarian purposes taken over by cheap enamelware brought in by Anglo traders. Hopi pottery production sputtered along until the 1880s when one woman, Nampeyo of Hano, almost single-handedly revived it. Nampeyo lived in Hano on First Mesa and was inspired by pot sherds found among the nearby ruins of the ancient village of Sikyátki. Like all the other potters around First Mesa at the time, Nampeyo was producing jars, bowls and canteens, often with one surface slipped white and decorated with designs in black-and/or-red. At the urging of Anglo traders' Alexander Stephen and Thomas Varker Keam, she began experimenting with polishing the surface of pieces coiled entirely of Jeddito yellow clay and then painting her designs directly on that. Today credit is given to Nampeyo for fully reviving the Sikyátki style. She was so good that Jesse Walter Fewkes, the first archaeologist to formally excavate Sikyátki, was concerned that her creations would shortly become confused with those made hundreds of years previously.

Sikyátki pottery shapes are very distinctive: flattened jars with wide shoulders; low, open serving bowls decorated inside; seed jars with small openings and flat tops; painting methods of splattering and stippling and very distinctive designs. The Sikyátki style seems to have evolved as various Zuni-, Keres- and Towa-speaking potters came together with Water Clan potters from the Hohokam areas of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, and they began working with clays found in the nearby Jeddito valley area. Over the years, other clans came to the area and made their own contributions to what we now refer to as "Sikyátki Polychrome." According to Jesse Walter Fewkes, that merging of styles, techniques and designs created some of the finest ceramics ever produced in prehistoric North America.

Today's Hopi Pottery

Most Hopi pottery is unmistakable in its shapes, colors and designs. The Hopis are blessed with multiple excellent clay sources, each offering a different deep color after polishing and firing. Most Hopi pottery uses a buff, red, white or yellow clay body. Some kachina carvers make pottery and sometimes carve and etch their surfaces. Most Hopi potters, though, form their pieces and paint their decorations using colors derived from boiled-down plants, watered-down clay and from crushed minerals.

Much of the symbology painted on Hopi pottery is themed with "bird elements:" eagle and parrot tails, feathers, beaks and wings, and with katsinam and permutations of migration patterns. Many Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Tewa potters are members of the Corn Clan and their annual religious cycle revolves around the seasons of corn. The vast majority of today's Hopi pottery shapes and the designs painted on them are obvious descendants of the work of potters who existed 200-and-more years ago.

The above paragraph applies mostly to potters from the vicinity of First Mesa. The few potters from Second and Third Mesas seem to derive their design palettes from farther back in time, to the geometric designs, patterns and figures of the rock art prevalent before the advent of the katsinam, and the emergence of the Medicine, Sacred Clown and Warrior societies 800 years ago.

Our Info Sources

Hopi-Tewa Pottery: 500 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 1998, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some info may be drawn from The Legacy of a Master Potter: Nampeyo and Her Descendants by Mary Ellen and Lawrence Blair, © 1999, Treasure Chest Books, Tucson.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.

Showing 1–12 of 52 results

-

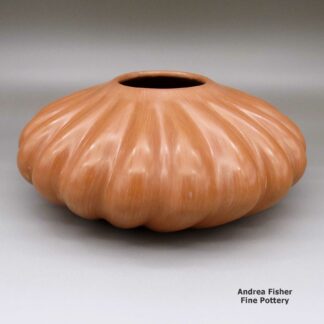

Alton Komalestewa, caho3a150, Red melon jar with 20 ribs

$7,600.00 Add to cart -

Annabelle Honie, cjho2k064, Polychrome jar with geometric design

$275.00 Add to cart -

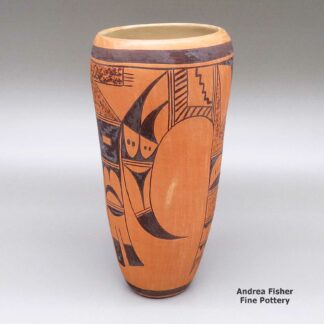

Barbara Polacca, zzho3b536, Cylinder with a bird element design

$425.00 Add to cart -

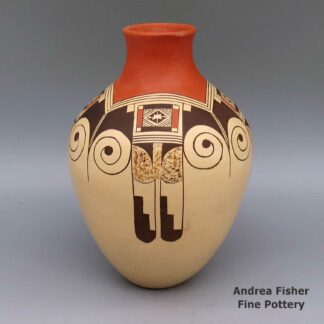

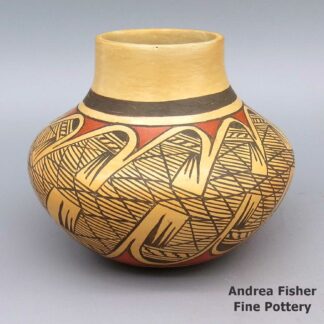

Clinton Polacca, esho2g020, Polychrome jar with geometric design

$650.00 Add to cart -

Dawn Navasie, esho2g068, Jar with geometric design

$450.00 Add to cart -

Elva Nampeyo, esho2g041, Polychrome jar with a geometric design and fire clouds

$595.00 Add to cart -

Elva Nampeyo, leho2h291, Polychrome jar with geometric design and fire clouds

$275.00 Add to cart -

Fannie Nampeyo, btho2l253, Polychrome jar with geometric design and fire clouds

$650.00 Add to cart -

Fannie Nampeyo, lkho2l304, Polychrome jar with geometric design and fire clouds

$2,800.00 Add to cart -

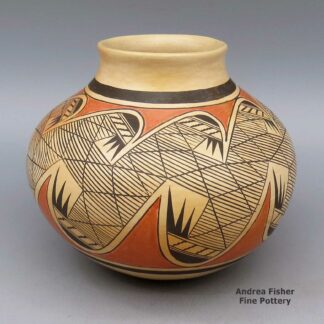

Fannie Nampeyo, lsho2g304, Polychrome jar with geometric design and fire clouds

$1,200.00 Add to cart -

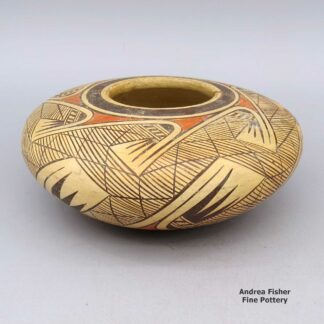

Fannie Nampeyo, zzho2m510, Polychrome bowl with a geometric design and fire clouds

$995.00 Add to cart -

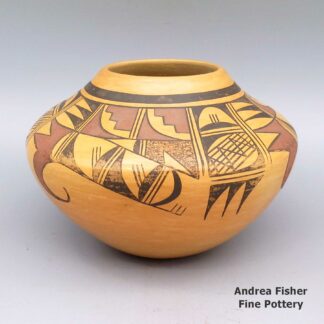

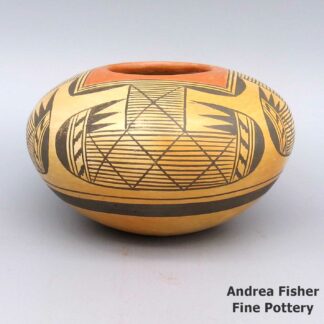

Garnet Pavatea, zzho3b524, Bowl with a geometric design

$250.00 Add to cart

Showing 1–12 of 52 results