Pojoaque

A Short History of Pojoaque Pueblo

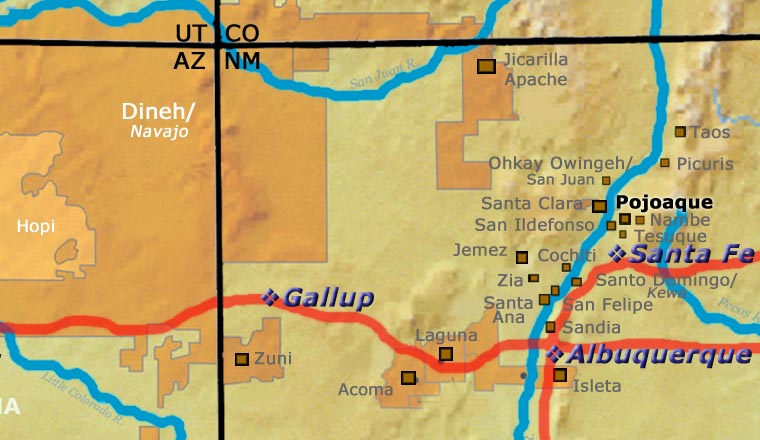

The Pojoaque Pueblo area was first settled around 500 CE and the population grew until it peaked in the 1500s. That was about the same time the Spanish arrived. The first Franciscan mission was built at the pueblo in the early 1600s but the people were already hurting under the impact of Spanish taxes, forced labor and continuous efforts to force conversion to Christianity. That all added up to Pojoaque being in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Immediately following the revolt, Pojoaque was abandoned and wasn't resettled until about 1706 when many Pojoaque's trickled back from the Cuartelejo area on the plains of west Kansas. The Cuartelejo area (now known as part the Dismal River culture) was beyond the bounds of New Spain. That area is where the Dineh and the various Apache tribes separated from each other and made their migrations east, south and west.

Other Pojoaques had gone to the top of Black Mesa (between San Ildefonso and Santa Clara on the eastern side of the Rio Grande) and joined with other Northern Tewas there to fight the Spanish. They held out for a couple years but finally made an agreement with the Spanish, came down off the mesa and returned to their former homes.

For the others, by 1706 the major Spanish retributions had died down and it was relatively safe to return, surrender and pledge allegiance anew. The Franciscan priests were also being replaced with Jesuits and the religious fervor receded from the heights reached during the Inquisition.

The population of the reestablished pueblo grew slowly over the next couple centuries but increasingly, they had to deal with problems from non-Indian encroachment. Finally, President Abraham Lincoln recognized the pueblo as an official tribe. Some documents say he awarded the tribe with an official land grant in 1864 and gave a silver cane to the tribe's governor (he gave silver canes to every pueblo president at the time and most of those canes are still in use). Other documents say the tribe was given a quit-claim deed... However it worked out, the tribe did gain some legal standing and was able to reestablish its presence until 1908 when a severe smallpox epidemic caused the pueblo to be abandoned again: the Cacique (the tribe's religious leader) died and Governor Jose Antonio Tapia left the reservation to find work. He took his family to Colorado and two generations later, most of them returned.

The Indian Re-Organization Act of 1933 forced the Bureau of Indian Affairs to get legal matters settled with every pueblo and reservation. A big problem in New Mexico was Anglo encroachment on tribal lands. When the market crash of 1929 happened and life went downhill for everyone, some non-Native families moved in and squatted in empty Pojoaque houses.

In 1934 the Commissioner of Indian Affairs placed newspaper ads around the area calling for all Pojoaque tribal members to come back and reoccupy their pueblo lands or tribal recognition and enrollment would be dissolved under the Indian Re-Organization Act. Shortly, 14 members of the Villareal, Tapia, Romero and Gutierrez/Montoya families returned and were awarded land grants from the Pueblo land base. By 1936 tribal enrollment reached 263 members and Pojoaque again became a Federally recognized Indian Reservation.

Jose Antonio Tapia's granddaughter, Cordelia Feliciana Viarrial Gomez, recounted her family returning to the pueblo in a covered wagon. She came back to the family home but there had been no upkeep, never mind modernization, in more than 20 years. There was no running water, no plumbing, no septic, no electric, no gas, no telephone.

Today, Pojoaque offers a major resort and golf course at Buffalo Thunder and two casinos in its commercial district. There's also a shopping mall, RV campground and various other Pueblo-owned enterprises. The Poeh Museum offers a look into Tewa and Pojoaque Pueblo history and culture. Poeh Museum also offers demonstrations and workshops given by various of the artists who have works displayed in the museum.

For more info:

Pojoaque Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Pojoaque official website

Office of the New Mexico State Historian

About the Pottery of Pojoaque Pueblo

During the time of abandonment, some Pojoaque members moved to nearby Ohkay Owingeh and Santa Clara Pueblos. Those Pojoaques who were making pottery at the time learned new things from their neighbors and when they later returned to Pojoaque, traditional pottery making changed with all the cross-pollination of styles and designs. Some potters, though, returned to making only traditional Pojoaque styles and designs. Today there is hardly any pottery being made at Pojoaque as so many tribal members are employed in one or another of Pojoaque's many commercial enterprises.

Our Info Sources

Pueblo Indian Pottery, 750 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2000, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.