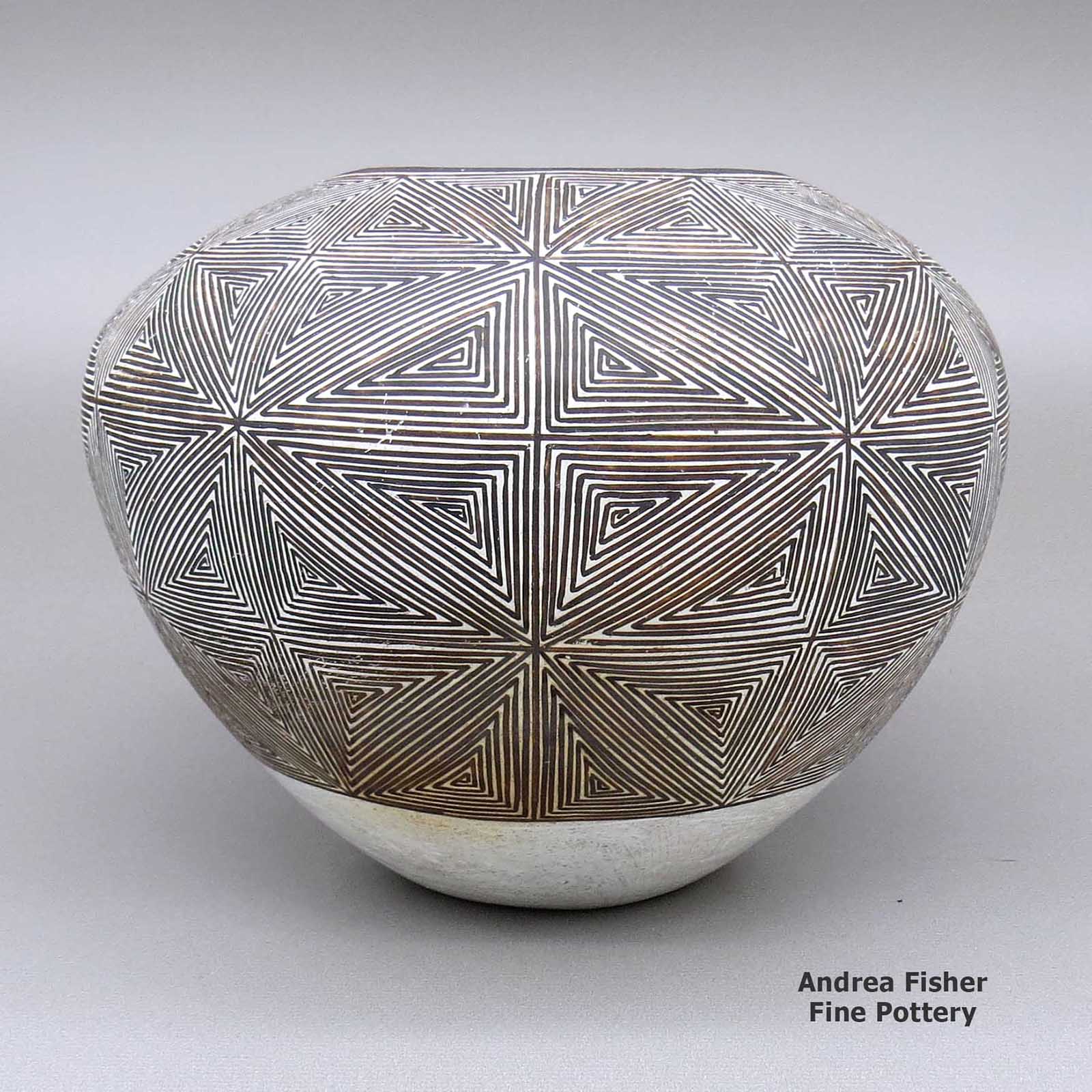

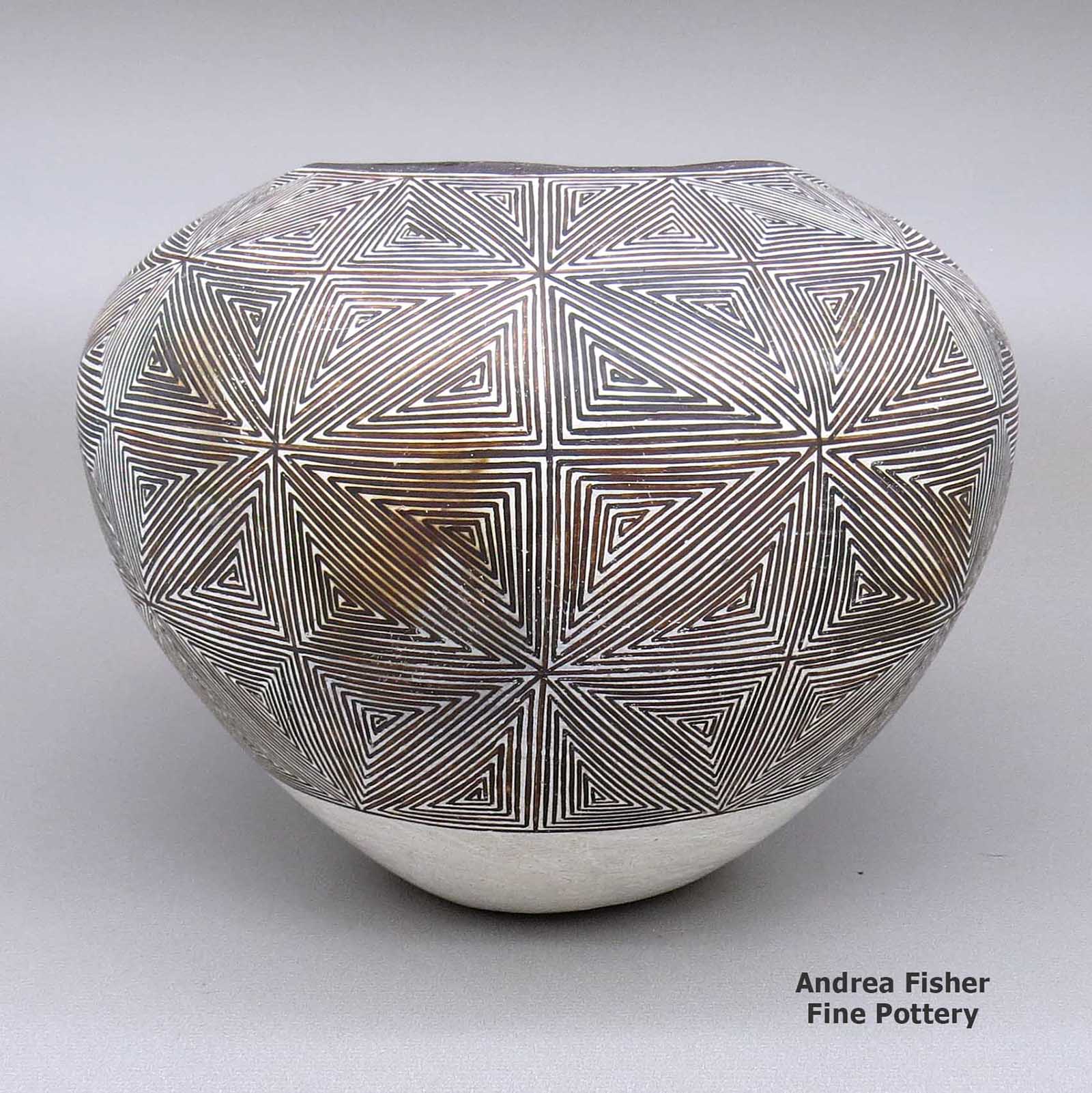

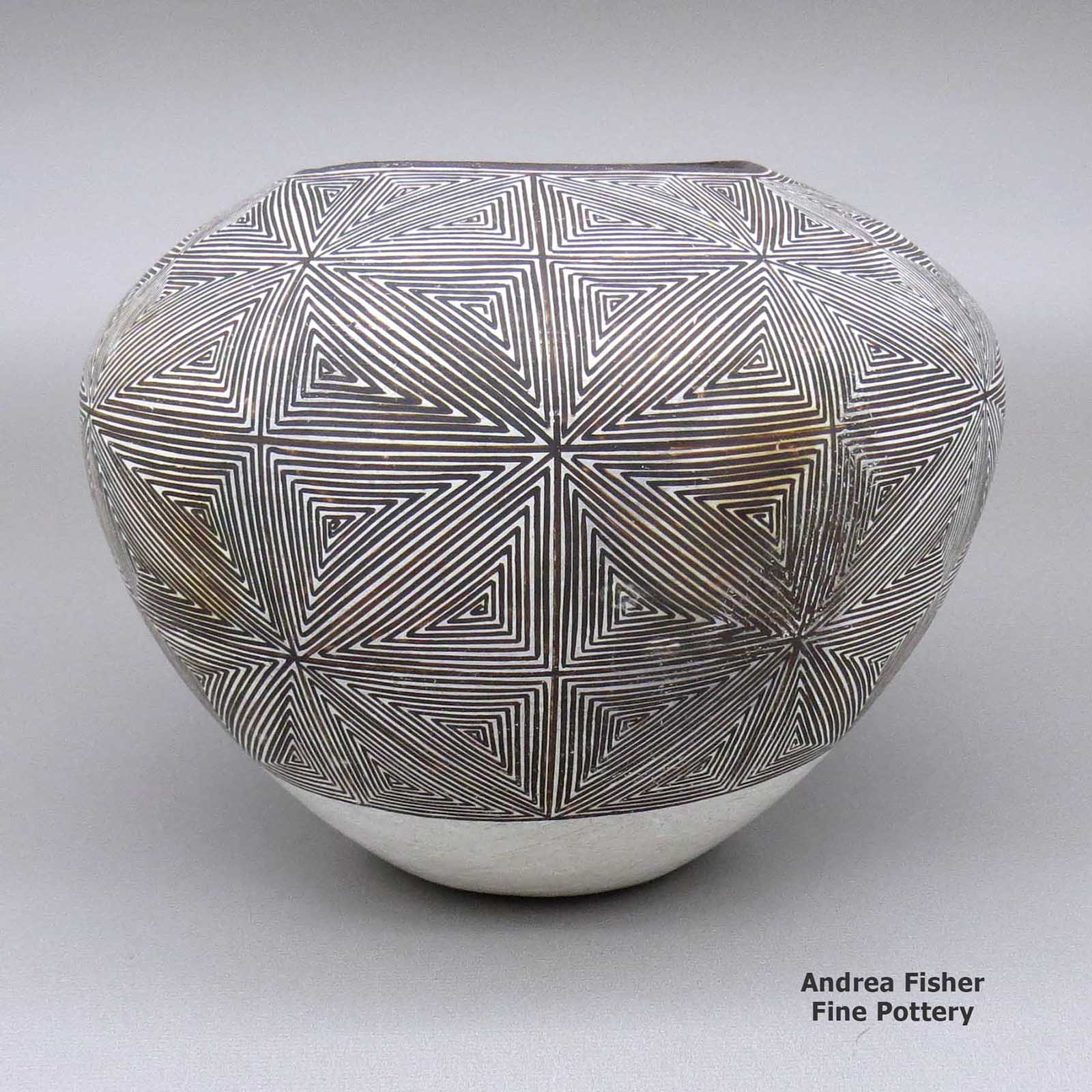

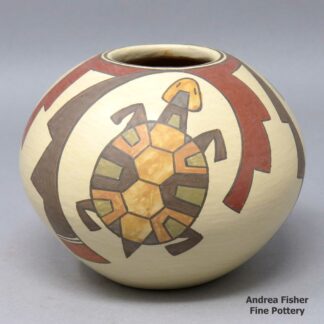

| Dimensions | 6.25 × 6.25 × 5.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has some scratches on design |

| Signature | Marie Z. Chino. Acoma, N.M. |

Marie Z Chino, dkac3c265, Black-on-white jar with a geometric design

$1,600.00

A black-on-white jar decorated with a snowflake fine line and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Chino, Marie Z

Marie Zieu Chino (1907-1982) was one of the Matriarchs of Acoma Pueblo pottery. Marie and her friends Lucy M. Lewis and Jessie Garcia are recognized as the three most important Acoma potters during the 1950s.

Together the three friends led the revival of ancient pottery forms and designs from the Tularosa, Mimbres, Anasazi and other ancient cultures from the region in central New Mexico. This revival spread among other Acoma potters who also allowed the old styles to lead them to innovative designs and new variations of style and form.

Marie and Lucy were friends but they were also competitors. Occasionally they copied each other's designs. According to Betty Toulouse in her 1977 book, Pueblo Pottery of the New Mexico Indians, Lucy didn't start making black-on-white jars with fine line hatching based on ancient designs until several years after Marie first did.

The inspirations for many of the designs used on their pottery were found on old pot sherds that had been gathered to use to make temper in their clay mixture. There are stories from the 1930s, too, about a cave filled with prehistoric pottery that had been kept hidden for generations. Those who knew of it only visited when they wanted to learn new designs. It is said that it is from that treasure trove that the Tularosa spiral made its reemergence in modern times.

Marie became particularly well known for her amazingly uniform fine-line designs in black-on-white hand-coiled pottery. Her pots were distinctive in their complex geometric designs as well as the combination of life forms and abstract symbols. Some of her favorite designs included animals, spirals, kiva steps, parrots, rainbows, berries, leaves, rain, clouds, lightning bolts and fine line snowflakes.

Marie was the daughter of Santiago and Lueppe Tsieyounow. Among her siblings were Francisco (Frank White), Leuppe Santana, Pablita S., Helen (Patricio), Juanico Santiago and Santana Zieu Sanchez (Chino). Marie's husband was Lorenzo Chino.

As the head of the Chino family of potters, Marie mentored her family in the finer aspects of the ancient art of pottery making. She also worked with many students from outside her family. Her children and grandchildren are numerous and include daughters Grace Chino, Rose Chino Garcia and Carrie Chino Charlie.

Marie Z. Chino's pottery can be found in the book, "14 Families in Pueblo Pottery" along with numerous other publications.

In 1922, Marie won her first ribbon at the Santa Fe Indian Market. She was only fifteen. She didn't participate in Indian Market again for years, then went on to receive numerous awards in Santa Fe for her pottery from 1970-1982. In 1998 the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts recognized Marie with a "Lifetime Achievement Award."

A Short History of Acoma Pueblo

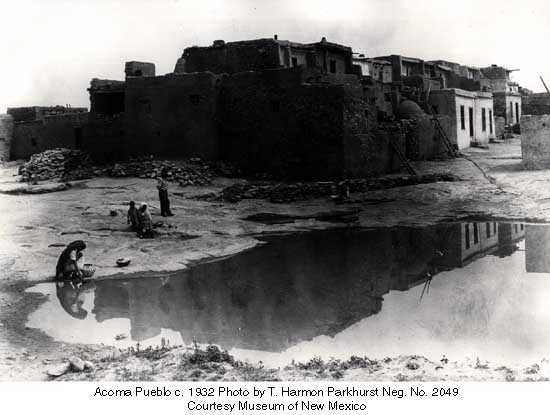

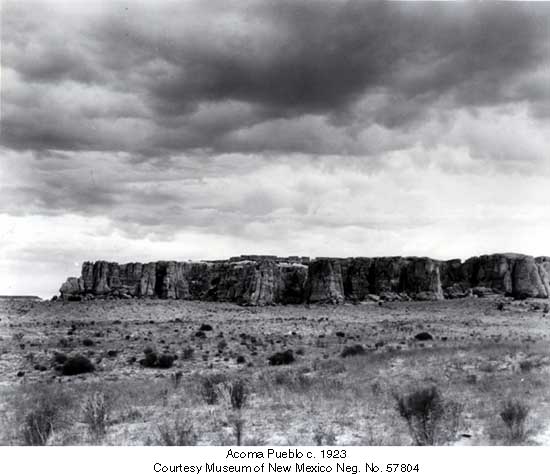

According to Acoma oral history, the sacred twins led their ancestors to "Ako." Ako turned out to be a magical mesa composed mostly of white rock. There the sacred twins instructed the ancestors to make that mesa their home. Acoma Pueblo is called "Sky City" because of its position atop the high mesa.

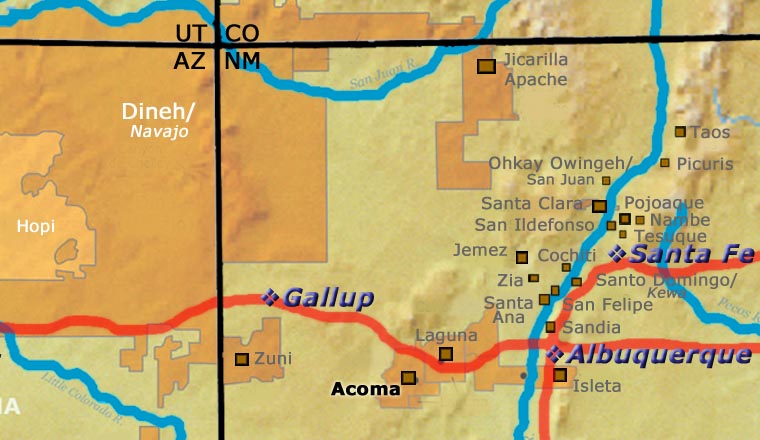

Acoma, Old Oraibi (at Hopi) and Taos all lay claim to being the oldest continuously inhabited community in the U.S. Those competing claims are hard to settle as each village can point to archaeological remnants close by to substantiate each village's claim. Acoma is located about 60 miles west of Albuquerque in a landscape littered with the ruins of ancient pueblos, many more than 1,000 years old.

The people of Acoma have an oral tradition that says they've been living in the same area for more than 2,000 years. Archaeologists feel more that the present pueblo was established near the end of the major migrations in the 1200 and 1300s. The location is essentially on the boundary between the Mogollon (Mimbres), Hohokam (Salado) and Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloan) cultures. Each of those cultures has had an impact on the styles and designs of Acoma pottery, especially since modern potters have been getting the inspiration for many of their designs from pot shards they have found while walking on pueblo lands.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado ascended the cliff to visit Acoma in 1540. He afterward wrote that he "repented having gone up to the place." But the Spanish came back later and kept coming back.

Around 1598 relations between the Spanish and the Acomas took a nasty turn with the arrival of Don Juan de Oñaté and the soldiers, settlers and Franciscan monks that accompanied him. After making the arduous ascent to the mesa top, de Oñaté decided to force the Acomas to swear loyalty to the King of Spain and to the Pope. When the Acomas realized what the Spanish meant by that, a group of Acoma warriors attacked a group of Spanish soldiers and killed 11 of them, including one of de Oñaté's nephews.

De Oñaté retaliated by attacking the pueblo. His troops burned most of it and killed more than 600 people. Another 500 people were imprisoned by the Spanish. Males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sold into slavery. 24 men over the age of 25 had their right foot amputated. Many of the women over the age of 12 were also forced into slavery. Most were parceled out among Catholic convents in Mexico City.

Two Hopi men were also captured at Acoma. The Spanish cut one hand off of each and sent them home to spread the word about Spain's resolve to subjugate the inhabitants of Nuevo Mexico. Spanish monks did make the trip a few years later but Spanish military made hardly an appearance in Hopiland.

When word of the massacre (and the punishments meted out after) got back to King Philip in Spain, he banished Don Juan de Oñaté from Nuevo Mexico. Some Acomas had escaped that fateful Spanish attack and returned to the mesa top in 1599 to begin rebuilding.

In 1620 a Royal Decree was issued which established civil offices in each pueblo and Acoma got its first governor. That didn't help the people any as those appointed to the government positions were also those most on the take with the Spanish authorities. By 1680, the situation between all of the pueblos and the Spanish had deteriorated to the point where the Acomas were extremely willing participants in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt.

After the successful Pueblo Revolt pushed the Spanish back to Mexico, refugees from other pueblos began to arrive at Acoma. Most feared the eventual Spanish return and probable reprisals. That strained the resources of Acoma badly. Then the Spanish returned in force and residents of the pueblo had to make a hard decision. Many of the refugees chose to try a peaceful solution: they relocated north to the ancient Laguna area and made peace with the Spanish as soon as they reappeared in the region. Acoma held out against the Spanish for awhile but soon capitulated.

Over the next 200 years, Acoma suffered from breakouts of smallpox and other European diseases to which they had no immunity. At times they would side with the Spanish against nomadic raiders from the Ute, Apache and Comanche tribes. Eventually New Mexico changed hands. Then the railroads arrived and Acoma became dependent on goods made in the outside world.

For many years the villagers were content on the mesa. Now most live in villages on the valley floor where water, electricity and other necessities are easily available. A few families still make their permanent home on the mesa top. The old pueblo is used almost exclusively these days for ceremonial celebrations.

For more info:

Acoma Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Acoma official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, © 2001

Acoma & Laguna Pottery, Rick Dillingham with Melinda Elliott, ISBN 0-933452-32-2, School of American Research Press, © 1992

Upper photo courtesy of Marshall Henrie, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Western Keresan Designs

Those of the Western Keres tradition have a plethora of traditional designs. A reason for that is they have occupied a region on the boundary between the Mogollon cultures to the south and the Ancestral Puebloan cultures to the north. And some of them have been living and working in the same place for a thousand years or more. They have also been making and breaking pottery the whole time. The area of Laguna has been more or less populated for a similar amount of time and, when populated, the Lagunas have moved around more than the Acomas.

Because Acoma and Laguna are located in that boundary area between Chaco Canyon influence to the north and Mogollon-Mimbres Valley influence to the south, designs and techniques have been coming and going across the landscape for many years. Over time, broken potsherds covered with multiple designs have fallen to the ground almost everywhere, just waiting to be picked up by someone, have their designs copied and revived, and their most basic constituents ground and mixed with fresh clay and to be reborn as pots again.

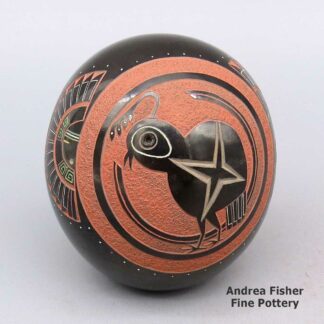

In the 1950s, that started happening a lot, potsherds being picked up and their designs revived, that is. Many of those designs have since been traced back to artisans in the Mimbres Valley working before 1150 CE. They had a unique perspective on the birds, animals, insects and people of their world, and used that perspective to draw and paint unique patterns. Many of those patterns are still being recreated on pottery across the Pueblo world, but especially at Acoma and Laguna. Central to the design palette are stories from the adventures of the Twin Warriors. While some Flower World iconography is also present in the Acoma design palette, there is extremely little from the kachina cults of the Hopi and Zuni.

One of the more recent "traditional" Acoma designs is the parrot holding a twig with berries in its claws. Often there is a rainbow above or below the parrot. Parrots are not natural in New Mexico, they had to have been imported. Before about 1450 CE, there was a trade in parrots and macaws through Paquimé to regions in the north. The remains of macaws have been pretty common but the remains of green parrots have only been recovered from three pueblos: Cicuyé, Paquimé and Grasshopper Pueblo in Arizona. The ancient-most Acoma parrot design has a Mimbres/Mogollon heritage while the parrot most painted today looks more like it came from an Amish trader's box. And it likely did.

With the arrival of Spanish colonists in New Mexico, pueblo potters changed their pottery to meet the demands of a new market. Their shapes and designs changed with that. Everything changed again with the arrival of Amish traders with their enameled cookware in the 1850s. The "new" Acoma parrot was pictured on the boxes those pots came in. The parrot came into being around 1880 and has been in use so long now it is considered "traditional."

Pottery was always in production at Acoma but from about 1600 to about 1950, it was heavily influenced by colonial shapes and designs. Eventually, the potters were reduced to producing items for the tourist trade to make ends meet, and that didn't go over so well either. Their own interest in making pottery fell off. Lucy Lewis, Jessie Garcia and Marie Z. Chino started decorating their pieces with their new interpretations of ancient Mimbres, Tularosa and Cibola designs in the 1920s and interest, both outside and inside the pueblo, grew again from there.

Laguna was impacted more heavily by the newcomers. Two Methodist missionaries married women in the pueblo and one of them shortly had himself elected President of the Pueblo. One of the first things he did was order the destruction of all the kivas on Laguna Pueblo land. That caused a schism and many Lagunas relocated to Isleta for a number of years (some of them are still there).

The Southern branch of the Transcontinental Railroad ran across Laguna Pueblo, and offered jobs to many of the men. That essentially ended the making of pottery by most tribal members. Then uranium was discovered under pueblo lands and more men went to work mining for that. Only a couple families passed the traditional knowledge down, until it eventually reached Evelyn Cheromiah. Nancy Winslow, an Anglo woman from Albuquerque, helped Evelyn obtain a grant to teach pottery making on the pueblo and a small revival started from there. Laguna potters, too, work their designs from designs they find on potsherds they find lying on the ground around the old pueblos. Their designs are very much like those of Acoma, usually just with more white space and bolder lines.

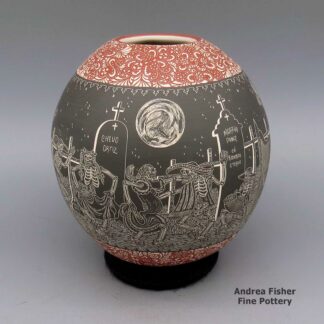

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

Marie Z. Chino Family Tree - Acoma Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Marie Zieu Chino (1907-1982)

- Carrie Chino Charlie (1925-2012)

- JoAnn Chino Garcia (1961-) & Lawrence Garcia Sr.

- Lawrence Garcia Jr.

- Trystyn Garcia

- Zachary Garcia

- Corinne Louis (1959-)

- JoAnn Chino Garcia (1961-) & Lawrence Garcia Sr.

- Rose Chino Garcia (1928-2000)

- Tena Garcia (1964-)

- Grace Chino (1929-1994)

- Gloria Chino (1955-)

- Carol Chino (1971-)

- Vera Chino Ely (1943-)

- Gilbert Chino (1946-1999)

- Emmalita Chino (daughter-in-law) (1931-) & Patrick Chino

- Patrick Patricio (1942-) & Doris Concho Patricio (1944-2019)

- Douglas Patricio

- Israel Patricio

- Myron Patricio

- Robert Patricio (1976-) & Melanie Patricio

- Felisha Patricio (1997-)

- Kylie Patricio (1999-)

- Juanita Patricio (2001-)

- Stephanie Patricio (1970- ) & Curtis Nez