About the Dineh

Historical and archaeological evidence points to the Dineh entering the Southwest around 1400 AD. Their oral history still contains stories of that migration as the journey began in eastern Alaska and northwestern Canada centuries after their ancestors made the journey across the Bering Land Bridge from central Asia about 10,000 years ago. They were primarily hunter-gatherers until they came into contact with the Pueblo peoples and learned the basics of survival in this drier climate. Dineh oral history points to a long relationship between the Dineh and the Ancestral Puebloans as they learned from and traded with each other.

When the Spanish first arrived, the Dineh occupied much of the area between the San Francisco Peaks (in Arizona), Hesperus Mountain and Blanca Peak (in Colorado) and Mount Taylor (in New Mexico). Spanish records indicate they traded bison meat, hides and stone to the Puebloans in exchange for maize and woven cotton goods. It was the Spanish who brought sheep to the New World and the Dineh took to sheep-herding quickly with sheep becoming a form of currency and sign of wealth.

When the Americans arrived in 1846, things began to change. The first fifteen years were marked by broken treaties and increasing raids and animosities on both sides. Finally, Brigadier General James H. Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to round up the Dineh and transport them to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico for internment. Carson succeeded only by engaging in a scorched earth campaign in which his troops swept through Dineh country killing anyone carrying a weapon and destroying any crops, livestock and dwellings they found. Facing starvation and death, the last band of Dineh surrendered at Canyon de Chelly.

Carson's campaign then led straight into "the Long Walk" to Bosque Redondo, a 300-mile trek during which at least 10% of the people died along the way. At Bosque Redondo they discovered the government had not allocated an adequate supply of water, livestock, provisions or firewood to support the 4,000-5,000 Dineh interned there. The Army also did little to protect the Dineh from raids by other tribes or by Anglo citizens. The failure was such that the Federal government and the Dineh negotiated a treaty that allowed the people to return to a reservation that was only a shadow of their former territory little more than a couple years after they had left. However, succeeding years have seen additions to the reservation until today it is the largest Native American Reservation in the 48 contiguous states.

Large deposits of uranium were discovered on the Dineh Nation after World War II but the mining that followed ignored basic environmental protection for the workers, waterways and land. The Dineh have made claims of high rates of cancer and lung disease from the environmental contamination but the Federal government has yet to offer comprehensive compensation.

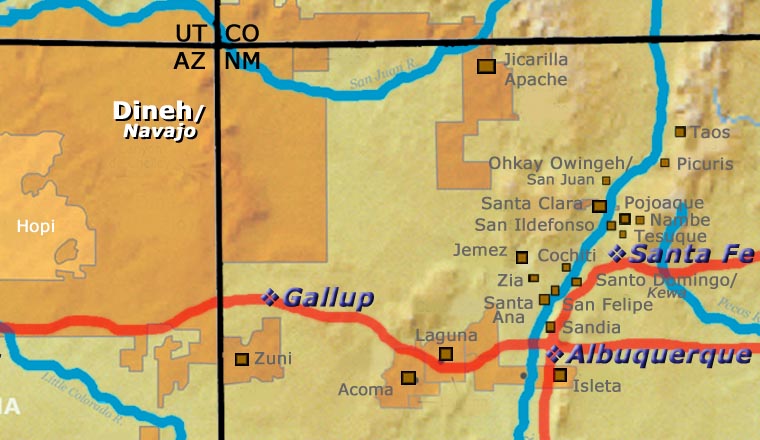

The location of the Dineh Nation

For more info:

Navajo Nation at Wikipedia

Diné people at Wikipedia

Navajo Nation Government official website

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Dineh Pottery

As a nomadic people, pottery didn't make much sense to the Dineh as they made the journey south from the northwestern corner of North America. When they came up against the Ancestral Puebloans they settled into a more sedentary lifestyle. The puebloans taught them much about how to survive in this climate on this landscape. That included the making of pottery for utilitarian purposes. That suited the Dineh religious authorities and as more and more Anglo settlers came into the area, they developed a business selling utilitarian wares to them. That essentially ended when the United States came into ownership of the land and American traders arrived with their relatively inexpensive and long-lasting enameled and cast iron cookware. Then pottery production scaled back to just ceremonial pieces being made.

Rose Williams learned how to make pottery from her aunt, Grace Barlow. Rose learned how to make basic brown pottery in utilitarian shapes. She only allowed herself the occasional rope biyo' for decoration, relying more on how she stacked her wood in the firing to make the fire clouds she wanted. Rose liked to make large brown jars which were often used to make drums. Living to be 99 years old and making pottery almost until she passed, Rose taught many people how to make pottery.

Grace Barlow also taught her granddaughter, Betty Manygoats. Betty in turn, taught all her children how to make pottery. Only Elizabeth has made a living at it.

Other modern potters on the reservation have usually learned how to make pottery the traditional way in the classrooms at the Institute for American Indian Arts.

Our Info Sources

Navajo Folk Art, by Chuck and Jan Rosenak, © 2008, Rio Nuevo Publishers.

Other info may be derived from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.