A Short History of Santa Ana Pueblo

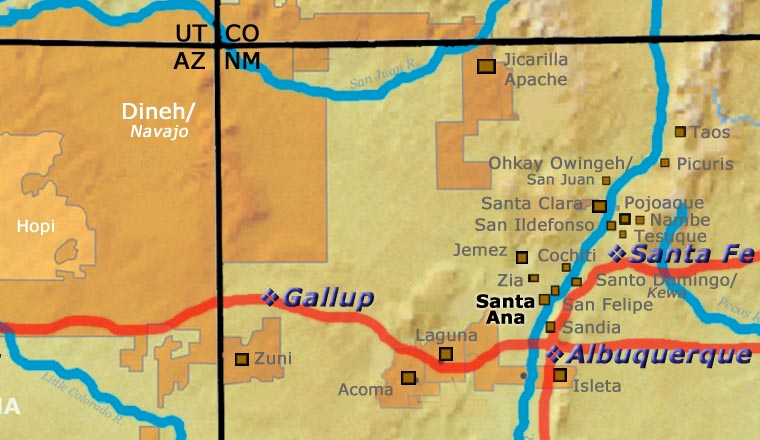

The Santa Ana people have occupied the area around today's pueblo since the early 1500s. As speakers of Eastern Keres, they most likely arrived from the area of Frijoles Canyon in what is now Bandelier National Monument, although they also could have come across the Jemez Mountains and downstream along the Jemez River. Tamaya, their first pueblo in the new location, was located against a south-facing rocky mesa wall on the north side of the Jemez River. That location was well off the usual trade and travel routes in the area, making Tamaya one of the most secluded of all New Mexico pueblos.

The first Spanish arrived in the area in the 1540s. Thankfully they didn't stay around long. There were a few visiting explorers over the years but no big push from the Spanish until 1598. Then things went downill quickly. Spanish abuses led to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 when the Pueblo peoples rose up together and forced the Spanish from Nuevo Mexico. Their freedom lasted for 12 years. Then in 1692, the Spanish returned in force, intent on staying.

In the fighting after the Spanish return, the Santa Anans were forced to flee from their village and the Spanish looted and burned it, destroying many of the buildings. The tribe fled into the Jemez Mountains and finally gathered on Black Mesa before descending into the valley and surrendering to Spanish rule again in 1693. One of the requirements was that they be baptized but they were still allowed to practice some of their tribal dances and traditions.

The tribe began rebuilding their pueblo and moved to acquire more agricultural land along the Rio Grande. They supplemented their diet by hunting and gathering. Slowly their tribal village industry economy shifted as more people became involved in the village agricultural economy. Their trade changed until they were offering food in return for pottery from their Zia and Jemez Pueblo neighbors.

Photo courtesy of John Phelan, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About the Pottery of Santa Ana Pueblo

Even in the days of the Spanish conquest, Santa Ana Pueblo was known more for its agricultural products than for its pottery. In the 1500s CE, the Santa Anas and the Jemez had a lively trade going with the Zias: food for pottery. That ended when Spanish military first arrived around 1600 CE. Then each pueblo had to develop its own pottery as travel and trade between the pueblos was restricted.

That eased after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 but none of the pueblos returned to the level of freedom and prosperity they enjoyed before the Spanish arrived. And in the interest of their own survival, each pueblo continued making their own pottery. Those potters often made ceremonial, commercial and utilitarian pottery at the same time.

Those pueblo members who still produced pottery in those days mostly emulated the creations of the Zias. Then the pueblo moved downstream closer to the Rio Grande and new sources of clay and temper were found. Still, by the 1920s, the Santa Ana pottery tradition was nearly extinct. Like most other pueblos, pottery making at Santa Ana almost completely disappeared during the 1940s and 1950s. Then Eudora Montoya (the last traditional Santa Ana potter at the time) began holding classes to teach what she knew to other women in the tribe in the 1970s. Today there are a few potters at Santa Ana but none produce a lot. They mostly make jars and decorate them with a design vocabulary of birds, cactus flowers and geometric designs.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.