About the Jicarilla Apache

The Jicarilla Apache lived a semi-nomadic existence for several thousand years, slowly making their way southward from the area of the Bering Land Bridge since the time of the last Ice Age. In the beginning, the tribe was part of a greater group that included all of those now known as Apache, Diné, Comanche, Kiowa and Ute. As they migrated southward, the group began to split into smaller groups based on how peaceful or warlike the members of each might be. Generally, the Navajos were considered more peaceful, the Apaches, Kiowa and Ute more warlike and Comanches most warlike. And among the Apaches there were similar differences with the Jicarillas being among the more peaceful.

Population pressures in the 1700s began to force them out of their more traditional territories in the southern and western plains. They had lived peacefully during most of that time, learning farming and pottery techniques from the Puebloan people with whom they traded and the Plains tribes taught them how to survive on the Great Plains.

The arrival of the Spanish and the westward push of the United States slowly forced them to move further and further into countryside not suited for their way of life. The mid-1800s were particularly bad for them as European diseases took a massive toll on their population.

Attempts to relocate the tribe onto a dedicated reservation began in the 1850s but the lands being allocated to them were not suitable for agriculture. Finally President Grover Cleveland created the Jicarilla Apache Reservation by an Executive Order in 1887. The piece of land the President set aside for the tribe held timber that they could sell, enough timber to finance the purchase of large tracts of land in the area more suitable for their traditional way of life.

In 1914 it was calculated that up to 90% of the tribe had contracted tuberculosis and in the 1920s it was feared the tribe might become extinct. After World War II oil and gas were discovered on the reservation and the royalties from that have made most of their lives more comfortable.

Photo is ours, all rights reserved.

About Jicarilla Apache Pottery

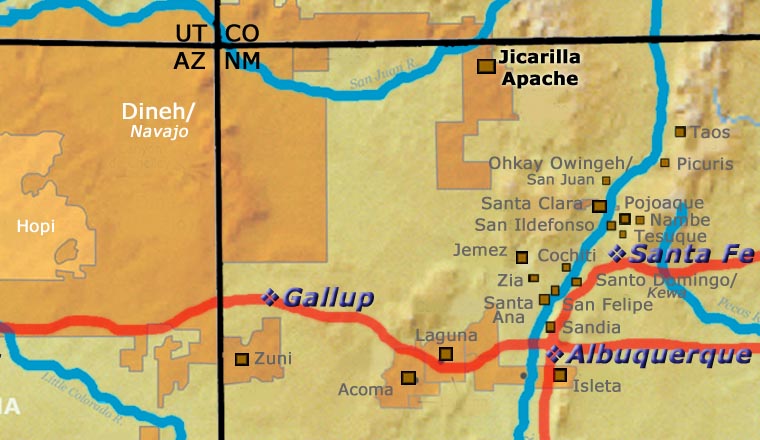

The Jicarilla Apaches have a long history of making pottery with some of their pots being found as far away as Kansas, Nebraska and the Black Hills of South Dakota. That trail begins around the valley of the Cimarron River and extends across the Purgatoire River Valley in Colorado northeast across the Arkansas River and into Kansas and Nebraska. It's in that area that the Dismal River Culture seems to have begun (the first site excavated in the area was close to the Dismal River in Nebraska). The Dismal River Culture is what ties the Black Hills of South Dakota to the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in New Mexico. The Cuartalejo village north of the Arkansas River in eastern Colorado was recognized by the Spanish as a refuge for most of the tribes under attack by the Spanish. It's from there that the trail of Jicarilla-made micaceous pottery followed the trail of the early Kiowas into the Black Hills. Eventually, they were pushed out of the Black Hills and relocated to the south, near the Comanche territories in Texas and Oklahoma.

For hundreds of years the Jicarilla Apaches have gotten their clay from sacred sites in northern New Mexico, as those were the areas where Jicarilla potters first learned how to make pottery. Their shapes and designs are very similar to those of Taos, and there are about the same number of Jicarilla potters as Taos potters still working today.

At the 1994 Micaceous Pottery Symposium at the School for Advanced Research, Felix Ortiz, a Jicarilla Apache potter, advanced the idea that the Jicarillas taught the potters of Taos and Picuris how to make pottery...

Our Info Resources

Some of the above info is drawn from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Some has been gleaned from Duane Anderson's All That Glitters: The Emergence of Native American Micaceous Art Pottery in Northern New Mexico, School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1999.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.