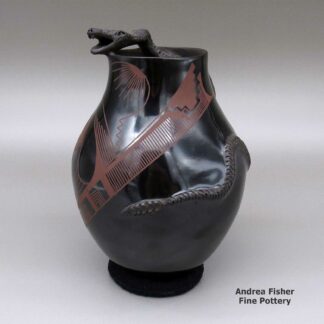

| Dimensions | 3.5 × 4.25 × 7.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Signature | BM |

| Date Born | 2022 |

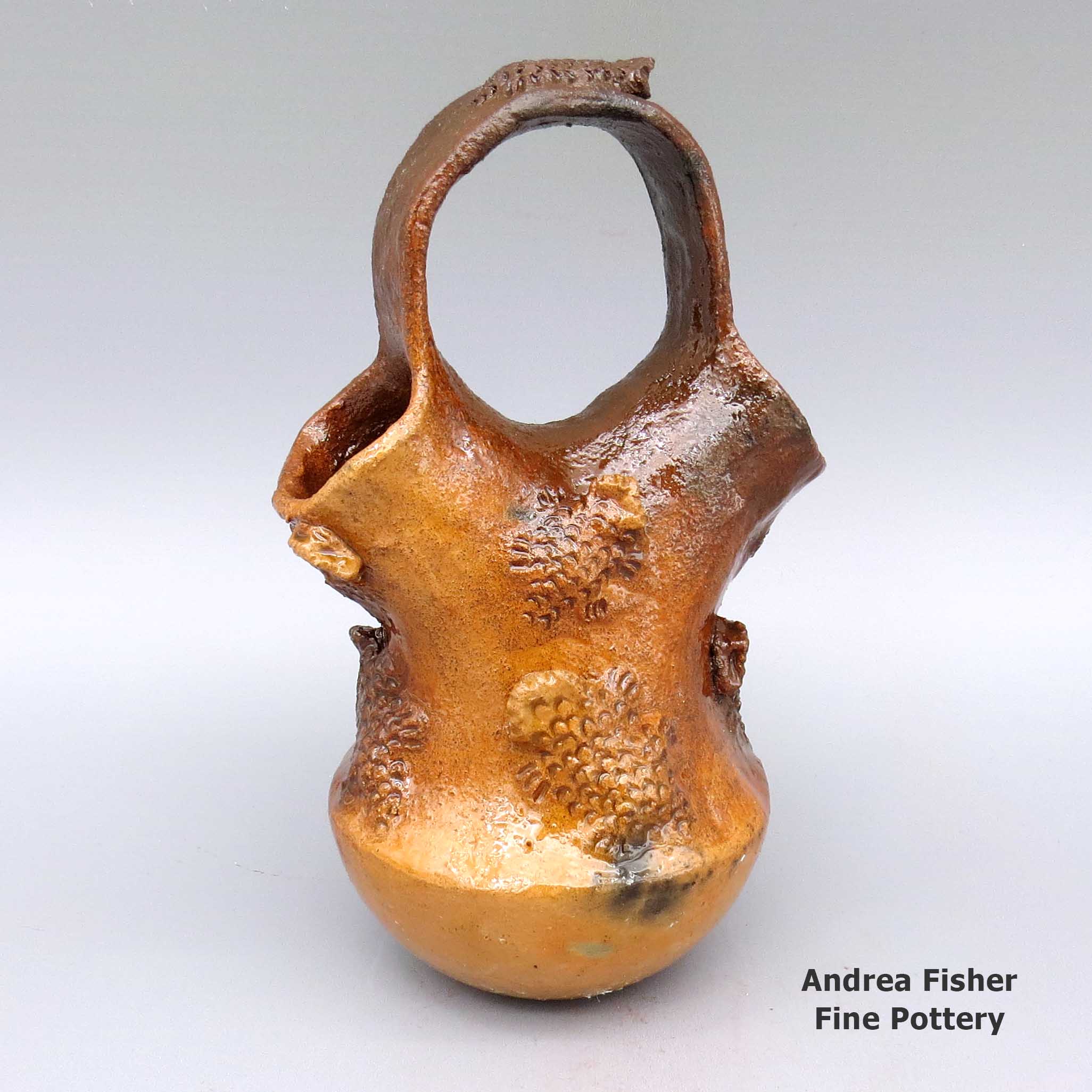

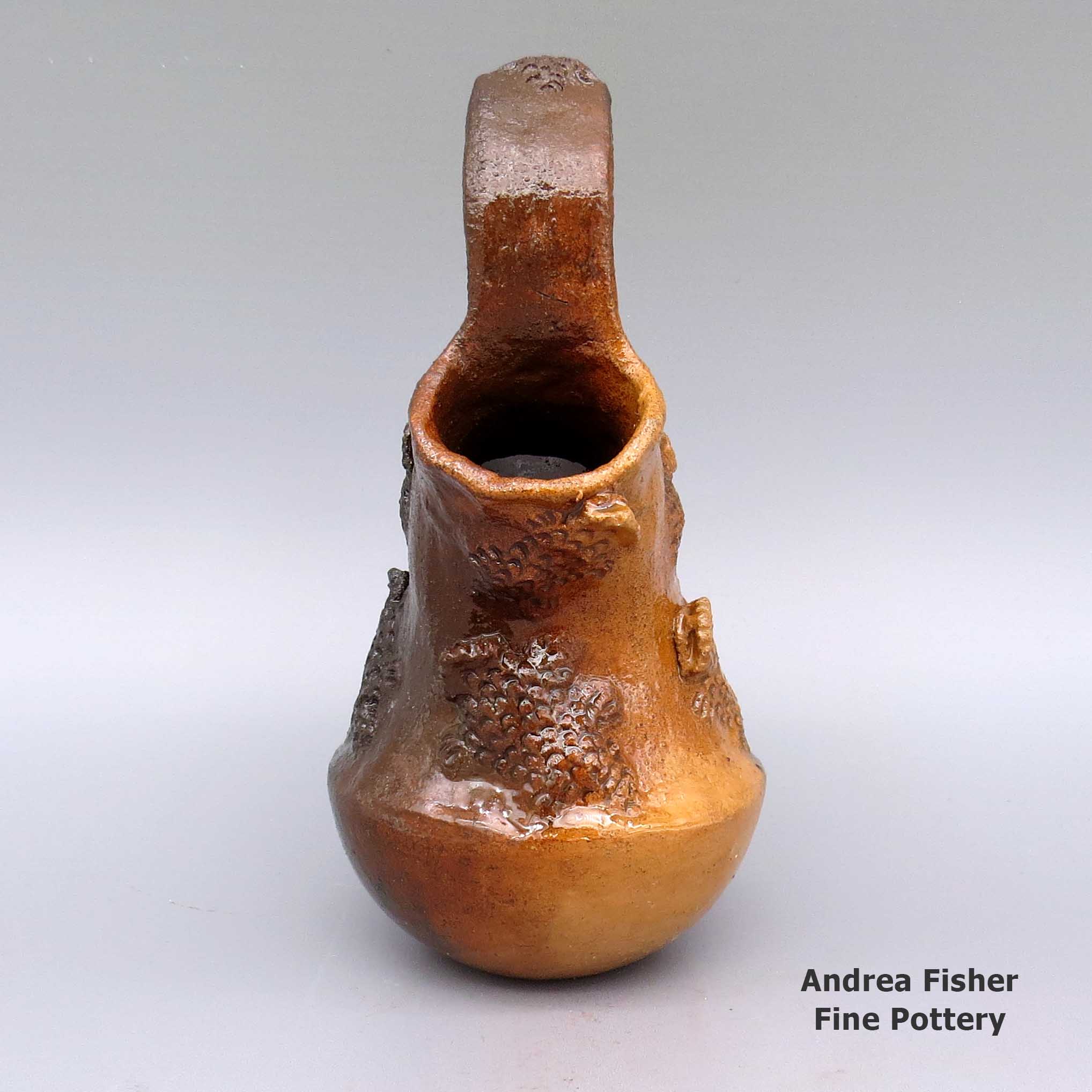

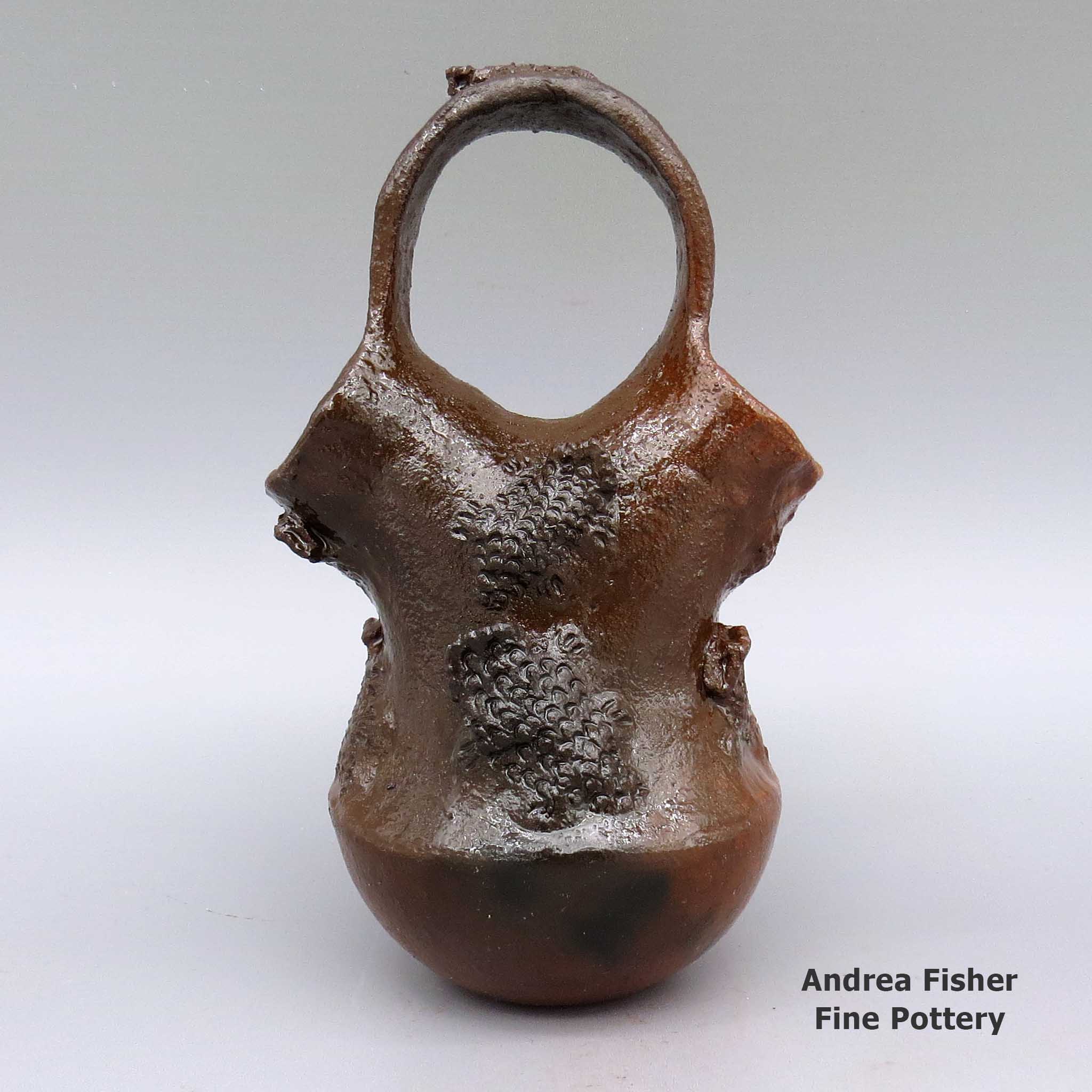

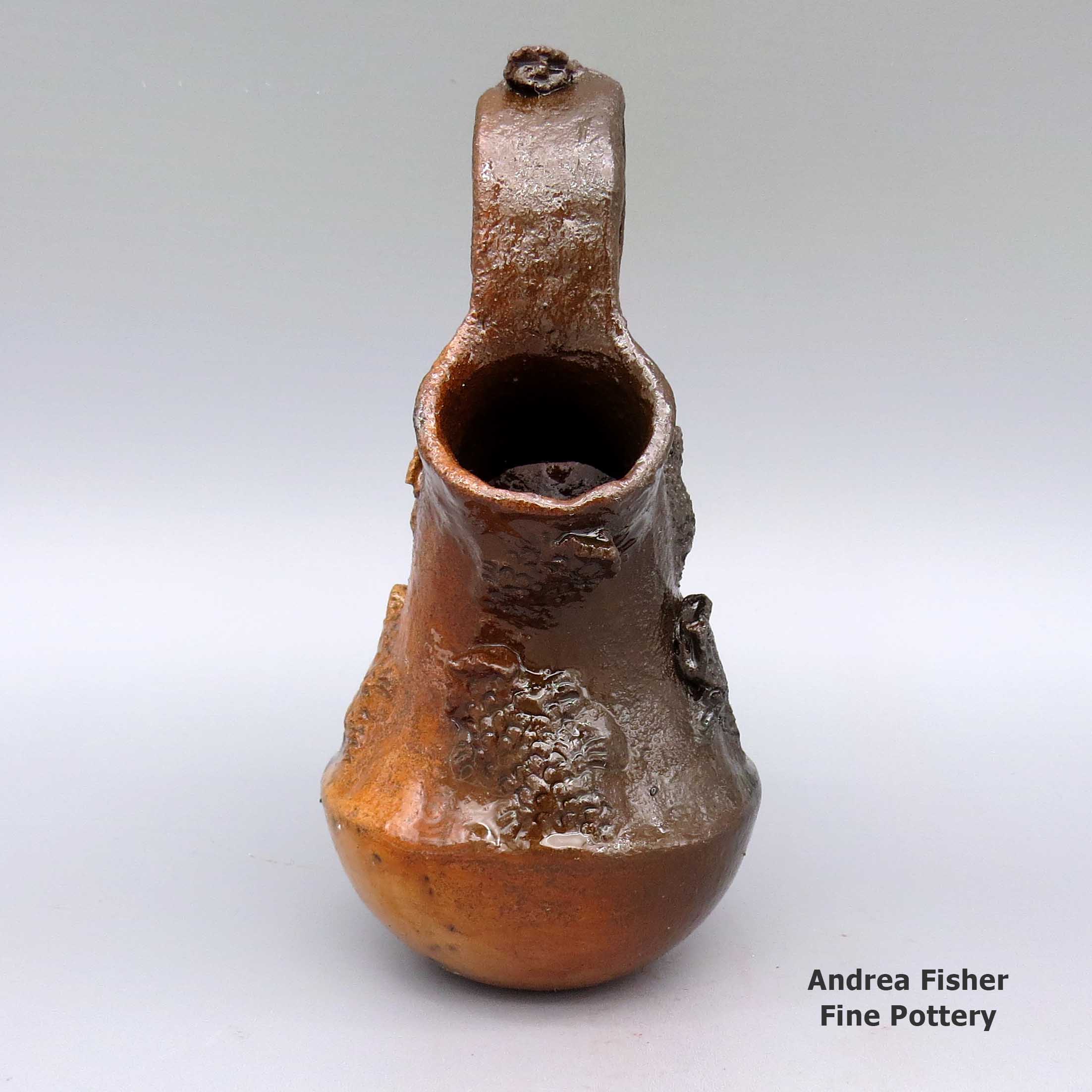

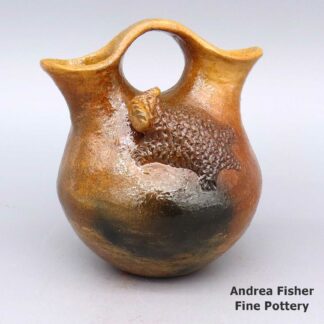

Betty Manygoats, zznv2h264m2, Wedding vase with appliques and fire clouds

$195.00

A brown wedding vase decorated with horned toad appliques and fire clouds

In stock

- Product Info

- About the Artist

- Home Village

- Design Source

- About the Shape

- About the Design

- Family Tree

Brand

Manygoats, Betty

Betty Manygoats doesn't speak English. She has always led a simple life in the remote reaches of the Navajo Nation, so remote she was home-schooled by her father because it was just too far to get her to a school. She was born Betty Barlow in January, 1945. She married William Manygoats 20 years later and they had one son and ten daughters.

Betty Manygoats doesn't speak English. She has always led a simple life in the remote reaches of the Navajo Nation, so remote she was home-schooled by her father because it was just too far to get her to a school. She was born Betty Barlow in January, 1945. She married William Manygoats 20 years later and they had one son and ten daughters.At the age of twenty-five her maternal grandmother, Grace Barlow, taught her how to make pitch pots. Shortly after that Betty was teaching Navajo pottery making at Tuba City High School.

Her most important students have been her own children and she still supervises their efforts and encourages them in the art. Breaking with Navajo tradition, her husband joins her in making pottery to help support their family.

Betty also went against Navajo teachings when she first put horned toads on her wedding vases. Traditional Dineh believe it best to avoid the horned toad and that "messing" with him brings bad luck. Being a Christian, Betty doesn't pay much attention to traditional superstitions. Besides, she's become rather famous for the horned toads that decorate her pieces.

Betty taught all her children how to make pottery and counts Elizabeth Manygoats, Rose Williams and Louise Goodman among her well-known potting relatives.

Over the years Betty participated in shows at the Museum of Northern Arizona in Flagstaff, the Santo Domingo Arts and Crafts Show at Santo Domingo Pueblo and the Window Rock Arts and Crafts Show in Window Rock, Arizona.

The traditional Dineh wedding vase with a bridge/handle spanning two spouts is Betty's favorite piece to make (with plenty of horned toads decorating the surface, too), but she is not limited in her scope of imagination or abilities. She uses the widest range of motifs on her pottery of any current Dineh potter and she occasionally paints her figures to add more detail. She sometimes has up to ten pieces at a time spread out on her kitchen table, all hand coiled, decorated and waiting to be ground fired, then coated with pine pitch.

Betty has not always signed her pots, but when she has she usually signs with her initials: BM or BBM (for Betty Barlow Manygoats). On occasion, she has signed her work with her name printed in full, "BETTY MANYGOATS", as well as in cursive signature style, "Betty B Manygoats".

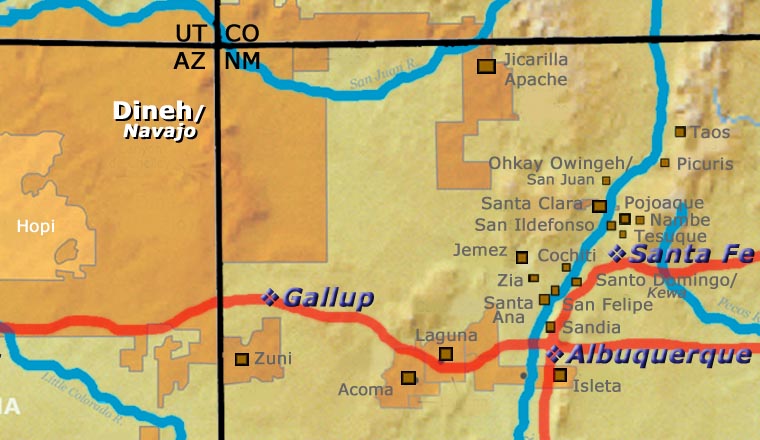

About the Dineh

Historical and archaeological evidence points to the Dineh entering the Southwest around 1400 AD. Their oral history still contains stories of that migration as the journey began in eastern Alaska and northwestern Canada centuries after their ancestors made the journey across the Bering Land Bridge from central Asia about 10,000 years ago. They were primarily hunter-gatherers until they came into contact with the Pueblo peoples and learned the basics of survival in this drier climate. Dineh oral history points to a long relationship between the Dineh and the Ancestral Puebloans as they learned from and traded with each other.

When the Spanish first arrived, the Dineh occupied much of the area between the San Francisco Peaks (in Arizona), Hesperus Mountain and Blanca Peak (in Colorado) and Mount Taylor (in New Mexico). Spanish records indicate they traded bison meat, hides and stone to the Puebloans in exchange for maize and woven cotton goods. It was the Spanish who brought sheep to the New World and the Dineh took to sheep-herding quickly with sheep becoming a form of currency and sign of wealth.

When the Americans arrived in 1846, things began to change. The first fifteen years were marked by broken treaties and increasing raids and animosities on both sides. Finally, Brigadier General James H. Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to round up the Dineh and transport them to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico for internment. Carson succeeded only by engaging in a scorched earth campaign in which his troops swept through Dineh country killing anyone carrying a weapon and destroying any crops, livestock and dwellings they found. Facing starvation and death, the last band of Dineh surrendered at Canyon de Chelly.

Carson's campaign then led straight into "the Long Walk" to Bosque Redondo, a 300-mile trek during which at least 10% of the people died along the way. At Bosque Redondo they discovered the government had not allocated an adequate supply of water, livestock, provisions or firewood to support the 4,000-5,000 Dineh interned there. The Army also did little to protect the Dineh from raids by other tribes or by Anglo citizens. The failure was such that the Federal government and the Dineh negotiated a treaty that allowed the people to return to a reservation that was only a shadow of their former territory little more than a couple years after they had left. However, succeeding years have seen additions to the reservation until today it is the largest Native American Reservation in the 48 contiguous states.

Large deposits of uranium were discovered on the Dineh Nation after World War II but the mining that followed ignored basic environmental protection for the workers, waterways and land. The Dineh have made claims of high rates of cancer and lung disease from the environmental contamination but the Federal government has yet to offer comprehensive compensation.

The location of the Dineh Nation

For more info:

Navajo Nation at Wikipedia

Diné people at Wikipedia

Navajo Nation Government official website

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Dineh Pottery

As a nomadic people, pottery didn't make much sense to the Dineh as they made the journey south from the northwestern corner of North America. When they came up against the Ancestral Puebloans they settled into a more sedentary lifestyle. The puebloans taught them much about how to survive in this climate on this landscape. That included the making of pottery for utilitarian purposes. That suited the Dineh religious authorities and as more and more Anglo settlers came into the area, they developed a business selling utilitarian wares to them. That essentially ended when the United States came into ownership of the land and American traders arrived with their relatively inexpensive and long-lasting enameled and cast iron cookware. Then pottery production scaled back to just ceremonial pieces being made.

Rose Williams learned how to make pottery from her aunt, Grace Barlow. Rose learned how to make basic brown pottery in utilitarian shapes. She only allowed herself the occasional rope biyo' for decoration, relying more on how she stacked her wood in the firing to make the fire clouds she wanted. Rose liked to make large brown jars which were often used to make drums. Living to be 99 years old and making pottery almost until she passed, Rose taught many people how to make pottery.

Grace Barlow also taught her granddaughter, Betty Manygoats. Betty in turn, taught all her children how to make pottery. Only Elizabeth has made a living at it.

Other modern potters on the reservation have usually learned how to make pottery the traditional way in the classrooms at the Institute for American Indian Arts.

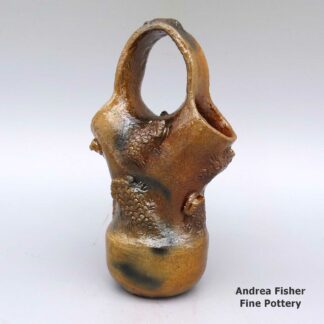

The Wedding Vase

- as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Native American wedding ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl’s parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy’s family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy’s home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy’s relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride’s home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom’s relatives and the bride’s parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom’s oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride’s oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom’s necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride’s is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride’s side, and the men from the groom’s.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride’s family feeds all the groom’s relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.

Appliqués

An appliqué is a clay figure formed separately and then added to another clay piece. Without using appliqués, it would be next to impossible to create a storyteller or a friendship bowl or a lifestyle pot. Some potters sculpt ear of corn appliqués while others sculpt figures or flowers or lizards, serpents, bugs or birds. Their use may be a relatively recent development but they can be found in use in most pueblos.

Grace Barlow Family and Teaching Tree - Dineh

Disclaimer: This "family and teaching tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this group and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

The only connections we've found between Grace Barlow and other Dineh potters are through her niece, Rose Williams, and her granddaughter, Betty Manygoats. It seems they all lived in a remote area near Coal Mine Mesa and they made pottery like in the old days: all the potters gathered together, worked together, and learned from each other. They made ceremonial and utilitarian pottery like in the old days: pottery-as-art is a new thing to the Dineh. Then many of the people were uprooted from the Coal Mine Mesa area and forced to move to Tuba City while the Hopi and Dineh lawyers fought it out in federal court. That took a couple decades but eventually the Dineh prevailed and they were allowed to return and live on their land again.

- Rose Williams (1915-2015), learned from her aunt, Grace Barlow

- Alice Cling (1946-)

- Susie Crank & Lorenzo Spencer

- Sue Ann Williams (1956- )

- Lorraine Williams-Yazzie (1955-)(former daughter-in-law)

- Stuart Roy (son-in-law)

- Raven Roy

- Stuart Roy (son-in-law)

- Silas Claw (1913-2002) & Bertha Claw (1926-)

- Faye Tso (1933-2004)

- Lorena Bartlett

- Louise Rose Goodman (student of Lorena) (1937-2015)

- Betty (Barlow) Manygoats (learned to make pottery from her paternal grandmother, Grace Barlow and from her cousin, Lorena Bartlett)

- Elizabeth Manygoats

- Evelyn Manygoats

- Evelyn Manygoats & Jonathan Chee

- Louise Manygoats

- Rita Manygoats