Gomez, Glenn

She broke a lump of clay in half and handed one piece to him, saying “make something with it, something that is made in your own style.”

Cordelia Feliciana Viarrial Gomez was the last surviving member of the group that returned in the 1930s to rebuild Pojoaque Pueblo (she died in 2017 at the age of 88). Her grandfather was José Antonio Tapia, the pueblo governor who had left in 1908 in search of work after smallpox, drought and incursions by Anglo settlers had devastated the pueblo. They returned when the Bureau of Indian Affairs under the Indian Re-Organization Act of 1933 called for all tribal members to return and form a tribal council or risk having their lands confiscated and their tribe decertified.

The people returned to a setting with no indoor plumbing, no running water, no electricity and no natural gas. Cordi lived through the upgrading of the pueblo, the building of schools and the establishment of modern business enterprises. Through those years she worked as a potter, seamstress, teacher and cook.

In 1988, her son, Glenn Gomez, was working on a road crew for the summer and looking at the soil they were digging in. He was admiring the colors of the dirt and the flecks of mica all through it. He finally asked his mother if that clay was what she used to make her pots. She pulled off a lump of her working clay and broke it in half. She handed Glenn one half and told him to “make something with it, something that is made in your own style.”

Glenn did, and he was enthralled with working with clay. He attended the Institute of American Indian Arts from 1989-1992 and earned an Associates of Fine Arts degree. In 1993 he became the “Artist in the Museum” at the Museum of Indian Arts & Culture in Santa Fe.

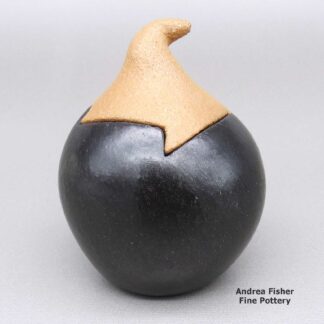

Glenn produced micaceous pottery: bowls, jars, canteens and figures. One of his chicken figure canteens is in the collection of the Poeh Museum at Pojoaque Pueblo.

Showing the single result

Showing the single result