Jemez Pueblo Pottery

Ancestors of the Jemez people were making a type of plainware pottery (simple, undecorated, utilitarian) when they were still in the Four Corners area, while others developed a distinctive type of black-on-white pottery. In moving to the Jemez Mountains, they brought their knowledge and techniques with them but had to adapt to the different materials available to work with.

There was a distinct break in the Jemez pottery tradition with the dislocations of the people after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Spanish concentrated a lot of their fury on the Jemez and the Jemez pushed back mightily. Slowly, the Spanish forced them all down out of their mountain retreats and into the Spanish-picked location at Walatowa. By 1740 their population was down to about 140 members.

Over time, they got better in their agricultural practices and began trading agricultural goods to the people of Zia Pueblo in return for pottery. By the mid-1700s, the Jemez were producing almost no pottery.

When general American interest in Puebloan pottery started to take off in the 1960s, the people of Jemez sought to recover that lost heritage but they had very little to work with. Today, the practice of traditional pottery-making is very much alive and well among the people of Jemez.

The focus of Jemez pottery today has turned to the making of storytellers, an art form that now accounts for more than half of their pottery production. Storytellers are usually grandparent figures with the figures of children attached to their bodies. The grandparents are pictured orally passing tribal songs and histories to their descendants. While this visual representation was first created at Cochiti Pueblo (a site in close geographical proximity to Jemez Pueblo) in the early 1960s by Helen Cordero, it speaks to the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren of every culture.

The vast majority of pottery vessels made at Jemez Pueblo today are not black-on-white. Instead, the potters have adopted many colors, styles and techniques from other pueblos to the point where Jemez potters no longer have one distinct style or design library of their own. The unique distinction they do have stems naturally from the materials they themselves acquire from their surroundings: it doesn’t matter what the shape or design or decorating color may be, the tan and red base clays and how they are incorporated into a pot say uniquely “Jemez.”

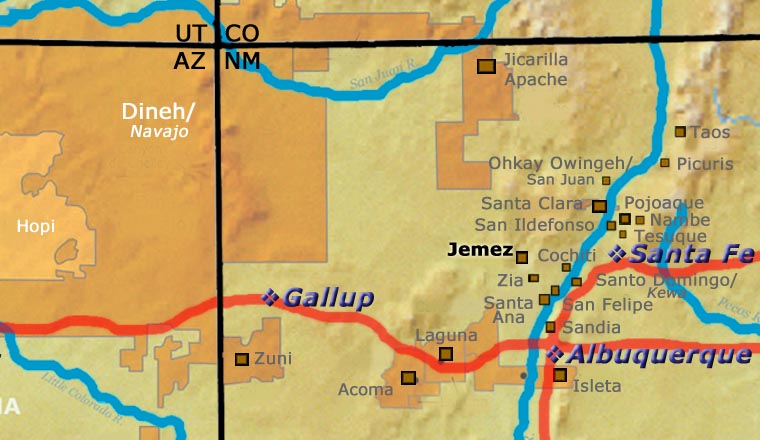

Recently, a former governor of Jemez Pueblo spent a decade researching and working to recover the process through which ancient black-on-white Jemez pottery was made. He was a devoted potter and he finally succeeded in his efforts with the pottery but his research also succeeded in pushing the early history of the Jemez people back to the Fremont Culture, around 200 CE. From west of the Colorado they moved to the southeastern Utah area and had a strong influence on the producers of San Juan Red Ware. Then they moved further down to the Upper San Juan Basin. Then many of them left again under the dark skies and bad weather at the end of the 1200s. Some went south and west to the Antelope Mesa-Jeddito Valley area where they built Awatovi and other, smaller pueblos. Others went east until they reached the Canyon de San Diego in the Jemez Mountains.