Quezada, Juan Sr

In many respects, the Paquimé Revival pottery of Mata Ortiz owes its birth to Juan Quezada Sr. As a young man, Juan was trying to get by as a farmer, cowherd and supplier of firewood in the vicinity of the village of Mata Ortiz. Each of these activities brought him into the ruins of what were formerly outlying villages and rancherias of the major pueblos of Paquimé and Casas Grandes.

By the time Spanish explorers reached the region in the early 1500s, Paquimé had been abandoned for a hundred years and was washing away more with each succeeding rainfall. However, the ruins impressed the Spanish as an example of a formerly wealthy New World community and perhaps spurred them on to find out where the gold went.

These days, the ruins of Paquimé are a designated United Nations World Heritage site. Much of the area has been excavated and a significant portion of the ruins have been stabilized so that erosion doesn’t have quite the effect it used to. That said, in some areas there are still ancient potsherds scattered all over the ground. To dig a few inches down is to expose many more.

There were also many unbroken pots unearthed in the area, pots showing a multitude of designs, shapes, forms and uses. Some of the designs and forms found have been traced back to the Mimbres culture of southern New Mexico and to possible Hohokam influences. Many of the Mimbres designs are still in use by potters across the Southwest Pueblo world.

Archaeologists have suggested that when the Mimbres people abandoned the Mimbres Valley in southern New Mexico around 1250 CE, some went north to the Acoma and Laguna areas and some went south to the area of Paquimé. The area of Paquimé may have been wetter in those days but by about 1400, it was getting pretty dry. Paquimé was completely abandoned by 1450 CE.

Juan Quezada Sr. often found himself wandering through the ruins of outlying villages, stepping on potsherds everywhere he went. Eventually he started picking them up and examining them. Then he stumbled across a cave that contained unbroken pots painted by the residents of Paquimé hundreds of years ago. That led to him trying to figure out how the pots were first made, then where the colors came from and how the designs fit together. With no tools to work with outside of his own drive to discover and his own ingenuity, it supposedly took him several years to figure it out.

Juan’s creations may have gone unnoticed except for the serendipitous discovery of a few of his pieces in a small shop in Deming, New Mexico by an Anglo trader named Spencer MacCallum. Spencer recognized quality when he saw it but it took him a while to follow the trail back to Juan. Once he’d met Juan, Spencer came up with a great marketing story and out of that marketing story grew the brilliance that is today’s Mata Ortiz pottery. And as good a potter as Juan was, that marketing story was not a true story. It did serve to make Juan famous in the United States but in Mexico, he’s almost unknown.

Juan had an exclusive contract with Spencer MacCallum for three years. By 1979 when the contract ended, there was a lot of friction around it, between Spencer and Juan and between Juan and other potters in Mata Ortiz. The marketing story started to unravel in the 1980s but it’s still being repeated in many places.

The meeting with Spencer MacCallum fueled Juan’s rise and as his pieces brought more and more income, his siblings got more and more interested in making pottery. Before long, Juan had taught them all how to do it and over the years since, many other potters have learned, made it their own and built their own careers. Many Mata Ortiz residents make and sell pottery into the United States and global markets and bring a level of prosperity to Mata Ortiz that the village has never known.

Juan is also the progenitor of the Quezada style, a design style that incorporates blank space into the overall design.

In contradistinction to that is the Porvenir style, originated by potters in the Porvenir neighborhood of Mata Ortiz. The Porvenir style essentially decorates every centimeter of a pot’s surface, leaving little-to-no blank space.

Juan retired and lived his last years on a ranch atop one of the hills above Mata Ortiz. He didn’t make much pottery any more but he did work with younger folks, teaching them the basics and some of his more advanced techniques. A lot of folks in Mata Ortiz owe their prosperity to Juan’s willingness to teach and pass on his knowledge and techniques. The Government of Mexico honored Juan by giving him the Premio Nacional de los Artes, the highest honor Mexico gives to its finest living artists. Sadly, Juan died at his ranch in December, 2022.

Showing all 4 results

-

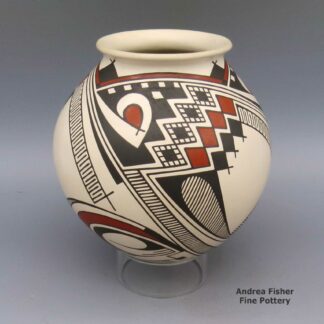

Juan Quezada Sr, cjcg2k060, Polychrome jar with geometric design

$1,500.00 Add to cart -

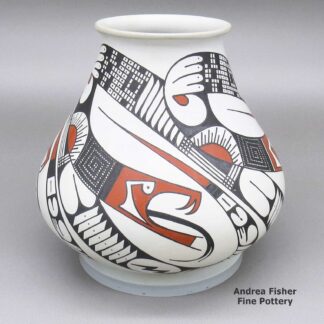

Juan Quezada Sr, crcg3b230, Polychrome jar with a serpent geometric design

$2,200.00 Add to cart -

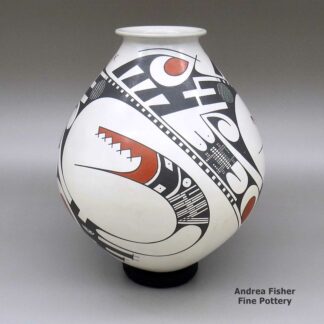

Juan Quezada Sr, thcg3b017, Jar with geometric design

$3,900.00 Add to cart -

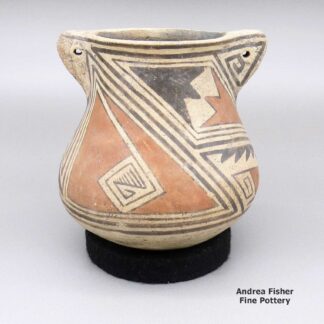

Juan Quezada Sr, thcg3b022, Jar with geometric design

$895.00 Add to cart

Showing all 4 results