Laguna Pueblo Pottery

Laguna and Acoma share the same language (Western Keres), similar pottery styles and similar religious beliefs. However, pottery making almost died out at Laguna after the railroads arrived in New Mexico in 1880 and laid a primary east-west trackbed directly in front of the Laguna main pueblo. During that time period many Lagunas went to work on railroad construction crews and many of the traditional Laguna arts and crafts died out. Pottery making never completely stopped at Laguna but by 1960 it was almost gone. Then Nancy Winslow and Evelyn Cheromiah met. Nancy was on a crusade to resurrect traditional pottery making in the pueblos where it had almost died out. Rick Dillingham quoted Evelyn Cheromiah as saying that after “looking at my mother’s pottery-making tools, I got the urge of going back to making pottery.” Nancy said she would come up with the funding if Evelyn would teach the class. So in 1973 and again in 1974 Evelyn Cheromiah taught two four-month arts and crafts classes at the pueblo. Among the 22 pueblo members in the first class were all of Evelyn’s daughters. That was the beginning of today’s renaissance in Laguna pottery.

Because of their geographic proximity, Laguna and Acoma clays are very similar. In some instances, it’s very hard to determine if a particular pot is from Acoma or from Laguna. Laguna potters, though, are more likely to temper their white clay with sand than with ground up pot sherds like the Acomas do. Laguna geometric designs also tend to be bolder than Acoma designs while Laguna potters use Mimbres designs much more sparingly than do Acoma potters.

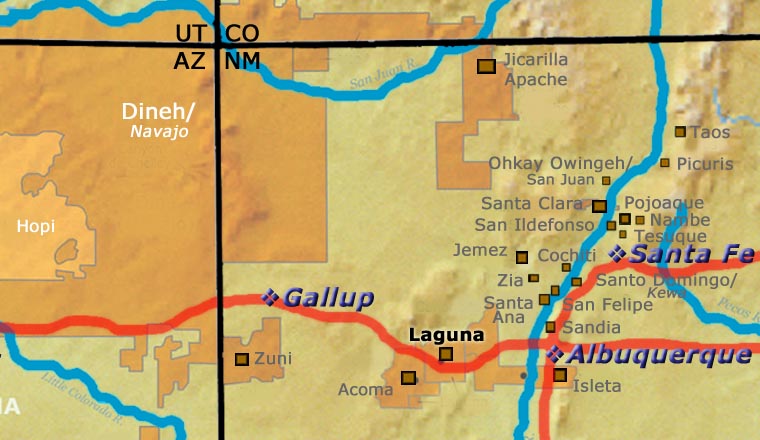

The Lagunas who relocated to Isleta in the late 1800s brought Laguna styles and designs with them. Isleta didn’t have a traditional design vocabulary so Laguna designs proliferated. When the tourists arrived in the 1920s, they were greeted at Isleta by a wild variety of products aimed purely at the tourist market. Laguna Polychrome was the source but after being adjusted for Isleta clays, it became Isleta Polychrome (although they still bought the base materials to produce their red and brown colors from Laguna). Isleta Polychrome is characterized by a wild variety of eccentric forms including bird effigies and baskets with twisted handles. The popularity of Isleta Polychrome wore off in the 1940s and the production of Laguna-style pottery at Isleta petered out.

There was a two-spirit person identified as Arroh-ah-och who lived at Laguna from about 1830 to the late 1890s. The Laguna pottery tradition was dying for most of her life. Virtually all the pottery that was being made was made for the tourist trade and was of inferior quality. However, there is a series of pots that are mostly in private collections but they stand out from the Laguna sequence of the time for their quality, their shapes and the designs painted on them.

Most of these pots have been attributed to the two-spirit person named Arroh-ah-och. Some were identified by family descendants (nieces and nephews), others by people very knowledgeable in the subject. Arroh-ah-och was a member of the Roadrunner clan, a clan that migrated to Laguna from Zuni in the 1800s. There has been speculation that she grew up at Zuni, moved to Acoma and learned to make pottery, then moved to Laguna. However, there has been testimony recorded from descendants indicating that she was born and grew up at Laguna, only going to visit Zuni to meet another two-spirit person named We’wha, later in her life.

We’wha became famous through her connection with ethnologist Matilda Cox Stephenson. Matilda and her husband, James Stephenson, were doing an ethnological survey at Zuni when they met We’wha. We’wha acted as a guide and translator for them (she had actually been assigned by the tribal elders to protect the purity and sanctity of the Zuni people and culture from them). A couple years later, Matilda took We’wha to Washington DC for six months where We’wha had a conversation with President Grover Cleveland and addressed Congress a couple times. In full regalia as a Zuni woman, no one ever suspected she was male. That said, We’wha was also an excellent weaver and potter, giving demonstrations of both at the Smithsonian Institute.

It is said that Arroh-ah-och was very impressed by We’wha’s pottery. She stayed at Zuni long enough for We’wha to teach her how to make it and how to paint the designs. When she returned to Laguna, she is the potter most likely to have made the pots in the above-mentioned series. However it was, the pots in this series were of significantly higher quality than the Laguna norm of the time. These pots also have Laguna shapes with layouts and designs that combine distinctly Zuni elements with Laguna elements. They are fine examples of how cross-pollination happens across Puebloan society.

The designs used by Laguna potters were picked up literally from pot sherds they found in the dirt around their homes. And as in most other pueblos, there is an ongoing movement at Laguna to bring back the pre-historic forms, shapes and designs.