A Short History of Isleta Pueblo

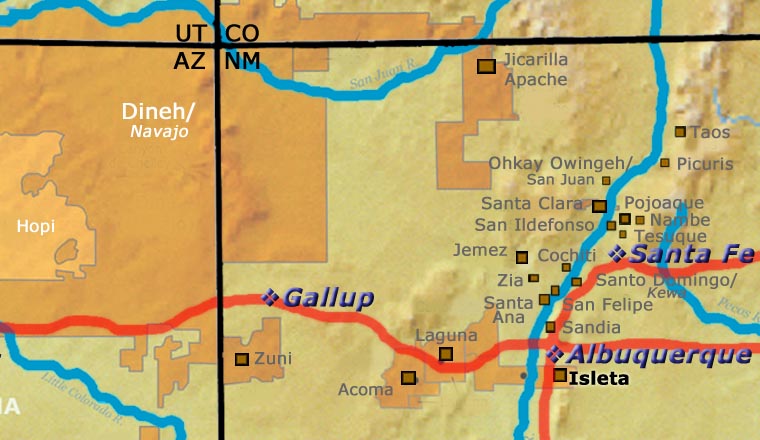

Isleta Pueblo was founded in the 1300s. Archaeologists have put forth various ideas as to where the people came from with some scholars saying they migrated north from Mogollon/Mimbres settlements to the south while others say they migrated southeastward from either Chaco Canyon in the 1100s and 1200s or from the Four Corners area in the 1200s and 1300s. There is every possibility they are an indigenous Tano population that was merged with Aztec migrants coming north from central Mexico and they were never part of the Chacoan world. Their Tiwa language is shared with nearby Sandia Pueblo and a very similar tongue is spoken to the north at Taos and Picuris Pueblos. The two dialects are sometimes referred to as Southern and Northern Tiwa. The Taos people also consider that some of their ancestors migrated north from Aztec lands long ago while others came from the north.

When the Spanish arrived in the area they named the pueblo "Isleta" (meaning: island). The residents were relatively accommodating to the Spanish priests when compared to the reception the same priests got in other areas of Nuevo Mexico (making Isleta something of an "island of safety" for the Spanish in an ocean of hostility). When the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 happened, Isleta either couldn't or wouldn't participate in the rebellion.

When the Spanish governor was evicted from Santa Fe he went to Albuquerque, then to Isleta and gathered his troops. With warriors from the northern pueblos harassing their every move, none of the Spaniards wanted to go back and fight so when they left Isleta and headed south, many Isletans went south to the El Paso area with them. Those who went south were allowed to establish their own pueblo at Ysleta del Sur, a place that at the time was beyond the boundaries of the village of El Paso.

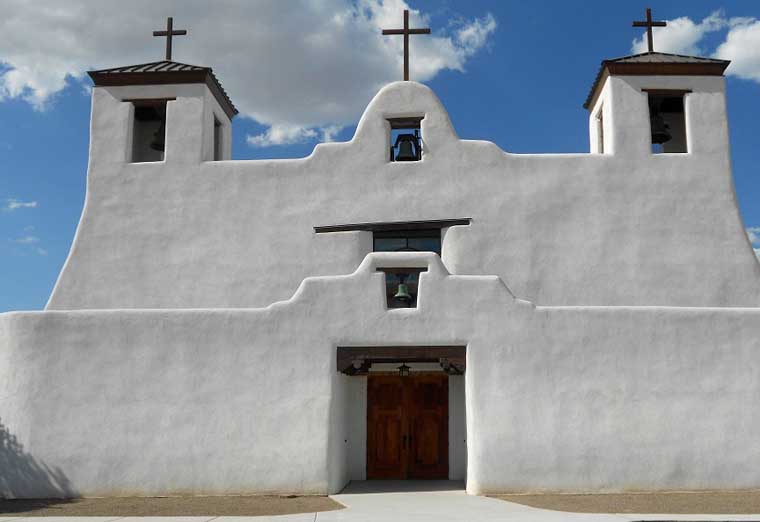

Other Isletans fled to the Hopi settlements in Arizona and returned after the fighting was clearly over, many with Hopi spouses. When the Spanish returned in 1682 they found the Isleta mission church burned and the main structure was being used as a livestock pen. When Don Diego de Vargas came in 1692 with troops intent on reconquering New Mexico, they found the whole village of Isleta empty and burned.

The governor ordered the pueblo be rebuilt and resettled so residents were brought in from Taos and Picuris to the north and from Ysleta del Sur to the south. By 1720 a new, more grandiose mission had been built on the foundations of the first.

Over the next century some dissident members of the Laguna and Acoma Pueblo communities migrated to Isleta. While they were welcomed into the main Isleta pueblo at first, friction developed over the years until in the late 1800s, the small communities of Oraibi and Chicale were established. Most of the newcomers moved to one or the other but some returned to Acoma and Laguna.

For more info:

Pueblo of Isleta at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Isleta official website

About the Pottery of Isleta Pueblo

The 1680 Pueblo Revolt virtually ended production of pottery at Isleta and it never really resumed. In the upheavals over the next hundred years, the entire Isletan design vocabulary was lost.

The advent of the railroad in New Mexico was almost the end of the Isleta community as so many of the men went to work for the railroad. Traders came in and convinced local potters, basket-weavers and silversmiths to make items for the tourist trade. Under the onslaught, pueblo artisans suffered until they stopped making much of anything and shifted their income to other avenues.

There was a surge of tourists in the 1920s that evoked a purely "for the tourist market" surge in the making of pottery. However, the pottery was mostly being made by Lagunas living at Isleta Pueblo. They got their base clay locally but they used a white slip and red and brown paints, all of which they bought from family at Laguna. As Isleta had no design tradition to work with, all the designs painted on the many different items made specifically for tourists were simple Laguna designs. There were ashtrays, small baskets with twisted handles, figurines, bowls with bird heads, pointy-toed moccasins, cigarette lighter cases, all kinds of knick-knacks and other stuff. The market for these grew large in the early 1920s and tapered off in the 1940s.

While the remaining residents managed to hold on to some of their social and religious practices, other elements of their culture almost disappeared. Pottery making is one of those traditions that barely survived. Like most other pueblos there was a move to bring pottery making back to Isleta in the 1950s and 1960s. A few Isleta potters became established making figures, wedding vases and seed pots but their ranks have not really increased since the early 1990s.

Today, making pottery the traditional way is practiced by only a few potters and their close family members.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.