A Short History of Laguna Pueblo

After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, many pueblo people were fearful of Spanish reprisals. Spanish militias returned in 1681, 1682, 1685 and again in 1689. That first return brought them as far north as Isleta and that pueblo was attacked, looted and burned. The second return saw troops marching up to Santa Ana and San Felipe, attacking, looting and burning both. In those years, when the Puebloans became aware of approaching Spanish forces they mostly scattered into the mountains and the Spanish found empty villages, easy to loot and easy to burn.

When Don Diego de Vargas marched north in 1692, he was intent on reconquering Nuevo Mexico and re-establishing a long-term Spanish presence there. As the conquistadors who accompanied him were on a "do-or-die" mission, the reconquest took on a tenor quite different from the previous missions...

At first de Vargas followed a path of reconciliation with the pueblos but that was soon replaced with an iron fist that brought on a second revolt in 1696. The pueblos didn't fare so well the second time around and a large number of Pueblo warriors were executed while their wives and children were forced into slavery. When word of de Vargas' actions got back to the King of Spain, he ordered de Vargas banned from the New World. However, most of the damage was already done.

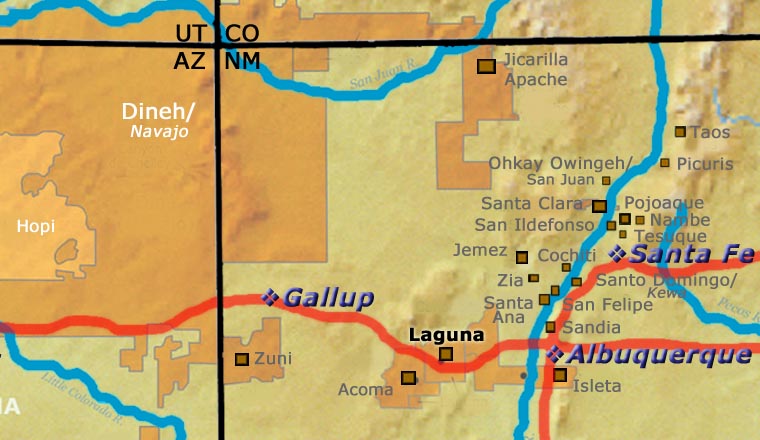

Many modern historians say Laguna Pueblo was established between 1697 and 1699 by refugees seeking to avoid fighting with the Spanish. Many of those refugees had left the first pueblos approached by the Spanish in 1692. First they scattered to more remote places like Acoma, Zuni and Hopi, or to more Spanish-friendly Isleta. However, the pressure of those refugees strained the resources of the other pueblos and quickly forced the refugees to consider starting a new existence in a newly-formed pueblo. The area of Laguna had been settled several hundred years previously by some ancestors of today's tribe. Other ancestors arrived during the periods of great drought that brought the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) down from the Four Corners area to the areas where we now find the Rio Grande Pueblos. Some of the land under Laguna control has also been found to contain archaeological resources dating as far back as 3,000 BCE.

The prehistoric village of Pottery Mound is located just east of today's Laguna Pueblo boundary on Isleta land. Some archaeologists have said that Pottery Mound has more different shapes and forms of pottery and more designs on it than any other pottery center in the Rio Grande area. Pottery Mound was abandoned before the Spanish first arrived but archaeologists have followed the tracks left by Pottery Mound styles, shapes and designs to settlements in the Hopi mesas and the Four Corners area.

Life was relatively quiet at Laguna until the 1860s. That's when the US Government started looking for a southern route to run a railroad across America to the Pacific Coast. The first route chosen ran right across Laguna Pueblo, not far from the village itself. The Marmon brothers, Presbyterian missionaries who were also land surveyors, were sent to Laguna to proselytize and to work as surveyors. Both brothers married prominent women in the pueblo and come 1872, one of them was elected President of Laguna Pueblo. He immediately acted to destroy the remaining kivas on pueblo land. That forced a schism in the tribe and many of the fundamentalists (as in: traditional Lagunas) relocated downstream and built a pueblo with kivas at Mesita.

After more interference from the Christian government at Old Laguna, many of the Mesita folks packed up and headed for Sandia Pueblo. But they chose to travel via Isleta Pueblo and ended up stuck there: Isleta offered them refuge only if they guaranteed their clan ritual masks (and other accoutrements) would remain at Isleta forever. A few years later there were problems at Isleta and some of the Lagunas returned to Mesita while most of the others moved northeast on Isleta land and built a couple of smaller pueblos nearer to the mountains.

Over time, several villages were established in the area around Old Laguna and when the Lagunas were granted their own reservation, they were given about 500,000 acres of land. That made Laguna one of the largest of all pueblos in terms of land. However, today only about half the enrolled members of the tribe live at Laguna as many have been drawn to nearby Albuquerque in search of work.

In the 1950s uranium was discovered on Laguna land and after forcing negotiations with the tribal council, a huge open-pit mine was developed near Paguaté. That provided good-paying jobs for a few years but it also contaminated their water and land with radioactive pollutants. Cleanup happens at a snail's pace but is supposedly ongoing.

Today Laguna operates a number of commercial and industrial enterprises, including the Route 66 Casino and Resort along Interstate 40 on the west bank of the Rio Puerco.

For more info:

Laguna Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Laguna official website

Discovering the Two-Spirit Artistry in the History of the Pueblo Pottery Revival, by Will Roscoe, © Feb. 2017

About Laguna Pueblo Pottery

Laguna and Acoma share the same language (Western Keres), similar pottery styles and similar religious beliefs. However, pottery making almost died out at Laguna after the railroads arrived in New Mexico in 1880 and laid a primary east-west trackbed directly in front of the Laguna main pueblo. During that time period many Lagunas went to work on railroad construction crews and many of the traditional Laguna arts and crafts died out. Pottery making never completely stopped at Laguna but by 1960 it was almost gone. Then Nancy Winslow and Evelyn Cheromiah met. Nancy was on a crusade to resurrect traditional pottery making in the pueblos where it had almost died out. Rick Dillingham quoted Evelyn Cheromiah as saying that after "looking at my mother's pottery-making tools, I got the urge of going back to making pottery." Nancy said she would come up with the funding if Evelyn would teach the class. So in 1973 and again in 1974 Evelyn Cheromiah taught two four-month arts and crafts classes at the pueblo. Among the 22 pueblo members in the first class were all of Evelyn's daughters. That was the beginning of today's renaissance in Laguna pottery.

Because of their geographic proximity, Laguna and Acoma clays are very similar. In some instances, it's very hard to determine if a particular pot is from Acoma or from Laguna. Laguna potters, though, are more likely to temper their white clay with sand than with ground up pot sherds like the Acomas do. Laguna geometric designs also tend to be bolder than Acoma designs while Laguna potters use Mimbres designs much more sparingly than do Acoma potters.

The Lagunas who relocated to Isleta in the late 1800s brought Laguna styles and designs with them. Isleta didn't have a traditional design vocabulary so Laguna designs proliferated. When the tourists arrived in the 1920s, they were greeted at Isleta by a wild variety of products aimed purely at the tourist market. Laguna Polychrome was the source but after being adjusted for Isleta clays, it became Isleta Polychrome (although they still bought the base materials to produce their red and brown colors from Laguna). Isleta Polychrome is characterized by a wild variety of eccentric forms including bird effigies and baskets with twisted handles. The popularity of Isleta Polychrome wore off in the 1940s and the production of Laguna-style pottery at Isleta petered out.

There was a two-spirit person identified as Arroh-ah-och who lived at Laguna from about 1830 to the late 1890s. The Laguna pottery tradition was dying for most of her life. Virtually all the pottery that was being made was made for the tourist trade and was of inferior quality. However, there is a series of pots that are mostly in private collections but they stand out from the Laguna sequence of the time for their quality, their shapes and the designs painted on them.

Most of these pots have been attributed to the two-spirit person named Arroh-ah-och. Some were identified by family descendants (nieces and nephews), others by people very knowledgeable in the subject. Arroh-ah-och was a member of the Roadrunner clan, a clan that migrated to Laguna from Zuni in the 1800s. There has been speculation that she grew up at Zuni, moved to Acoma and learned to make pottery, then moved to Laguna. However, there has been testimony recorded from descendants indicating that she was born and grew up at Laguna, only going to visit Zuni to meet another two-spirit person named We'wha, later in her life.

We'wha became famous through her connection with ethnologist Matilda Cox Stephenson. Matilda and her husband, James Stephenson, were doing an ethnological survey at Zuni when they met We'wha. We'wha acted as a guide and translator for them (she had actually been assigned by the tribal elders to protect the purity and sanctity of the Zuni people and culture from them). A couple years later, Matilda took We'wha to Washington DC for six months where We'wha had a conversation with President Grover Cleveland and addressed Congress a couple times. In full regalia as a Zuni woman, no one ever suspected she was male. That said, We'wha was also an excellent weaver and potter, giving demonstrations of both at the Smithsonian Institute.

It is said that Arroh-ah-och was very impressed by We'wha's pottery. She stayed at Zuni long enough for We'wha to teach her how to make it and how to paint the designs. When she returned to Laguna, she is the potter most likely to have made the pots in the above-mentioned series. However it was, the pots in this series were of significantly higher quality than the Laguna norm of the time. These pots also have Laguna shapes with layouts and designs that combine distinctly Zuni elements with Laguna elements. They are fine examples of how cross-pollination happens across Puebloan society.

The designs used by Laguna potters were picked up literally from pot sherds they found in the dirt around their homes. And as in most other pueblos, there is an ongoing movement at Laguna to bring back the pre-historic forms, shapes and designs.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.