A Short History of Ohkay Owingeh

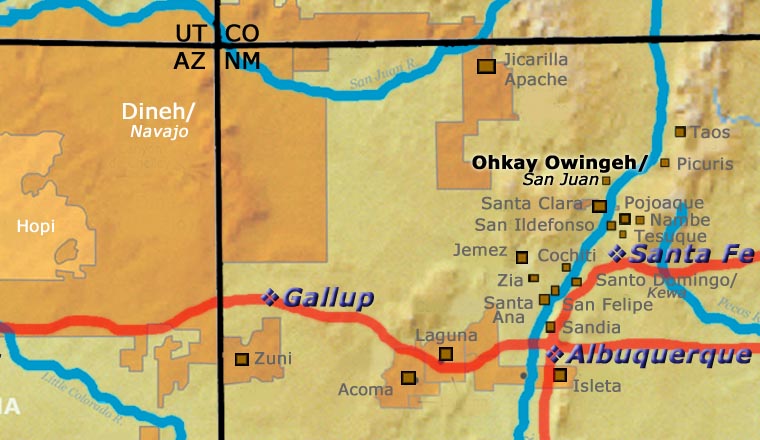

In 2005 San Juan Pueblo officially changed its name back to its original name (before the Spanish arrived): Ohkay Owingeh (meaning: Place of the strong people). The pueblo was founded after 1200 CE during the time of the great Southwest drought and migrations. The people speak Tewa and may have come to the Rio Grande area from southwestern Colorado or from the San Luis Valley in central Colorado.

Spanish conquistador Don Juan de Oñate took control of the pueblo in 1598, renaming it San Juan de los Caballeros (after his patron saint, John the Baptist). He established the first Spanish capitol of Nuevo Mexico across the Rio Grande in an area he named San Gabriel. In 1608, the capitol was moved south to an uninhabited area that became the Santa Fe we know today.

After 80 years of progressively deteriorating living conditions under Spanish rule, the people of Ohkay Owingeh participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 (one of the revolt's ringleaders, Popé, was a spiritual leader at Ohkay Owingeh) and helped to expel the Spanish from Nuevo Mexico for 12 years. However, when the Spanish returned in 1692 that tribal unity had fallen apart and the individual pueblos were relatively easy for the Spanish to reconquer.

Today, Ohkay Owingeh is the largest Tewa-speaking pueblo (in population and land) but few of the younger generations are interested in carrying on with many of the tribe's traditional arts and crafts (such as the making of pottery). The pueblo is home to the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Council, the Oke-Oweenge Arts Cooperative, the San Juan Lakes Recreation Area and the Ohkay Casino & Resort. The tribe's Tsay Corporation is one of northern New Mexico's largest private employers.

For more info:

Ohkay Owingeh at Wikipedia

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

About the Pottery of Ohkay Owingeh

When Don Juan de Oñaté and his troops arrived in 1598, the people of Ohkay Owingeh had been a fractured family for almost 400 years. The two sides of the family lived on opposite sides of the Rio Grande. When the Spanish arrived, the people offered them the western pueblo as guest quarters while all those people who lived in the western pueblo moved to the eastern pueblo. De Oñaté and his men occupied the emptied pueblo but it wasn't enough. De Oñaté was kind enough to go to the eastern pueblo the next day and claim and rename it "San Juan de los Caballeros." Then he made the eastern pueblo his capitol. The quality of life and the quality of pottery made in the pueblo declined precipitously after that.

The Spanish remained in the "guest quarters" for ten years before moving 30 miles south to their new capitol at La Villareal de la Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asis in 1608. At Santa Fe they probably felt safer: they weren't completely surrounded by people they'd abused horribly. But their abuse of the natives got continually worse, leading to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680.

In that Revolt, led by Popé, a medicine man from Ohkay Owingeh, many Spanish settlers, soldiers and priests were killed while the rest were chased south to El Paso. The Spanish came back in force in 1692 and reoccupied Santa Fe. They made it to San Juan in 1696. They found the village deserted.

It was ten years before the people started coming back to the pueblo. The Spanish yoke wasn't as onerous this time around so some native religious activities resumed. By the late 1800s, San Juan potters had made a comeback based on the amount of utilitarian wares produced in the pueblo and distributed through the surrounding countryside. It was all purely utilitarian, no decorations. But around 1900, pottery making just faded out. In 1920 when revivals were in full bloom at nearby Santa Clara and San Ildefonso Pueblos, there were no working potters at San Juan.

In the 1930s, a group of women came together and worked out a baseline for a San Juan pottery tradition. What they settled on were shapes and designs found at a construction site on the west side of the Rio Grande on Pueblo land. Those pieces were dated to have been made between about 1450 and 1500 CE, well before any influence from the Spanish.

After some experimentation and refinement, the definition of the "new" San Juan pottery style (named Potsuwi'i) consists mostly of red and tan ware and is often heavier than previous San Juan pottery. The rim and base of a fired Potsuwi'i pot are usually a polished deep red with an unslipped, buff-colored band in between. The central band is either carved with a geometric design, decorated with red, buff and white matte paints or incised with a micaceous slip applied before firing. Or all of the above. Typical designs include geometric patterns, flowers, feathers, kiva steps, spirals, rainbows and sun/cloud patterns.

The technical description of Potsuwi'i Incised Ware from around 1500 CE attests to the height of artistic and technical expression reached at the time. Coronado passed nearby around 1540 and no one really noticed. But when Don Juan de Oñaté established his capitol at San Juan de los Caballeros in 1598, everything went downhill for the people of Ohkay Owingeh quickly. It was almost 400 years before they even legally got their name (Ohkay Owingeh) back.

In 1931 those seven women went to work and established a market for their pottery before the year was out. They were never prolific but they were quite artistic in their endeavors. By the 1960s, though, there were only a couple of them left and they weren't making pottery any more.

In 1968 the Oke Oweenge Arts Cooperative was formed and that provided the impetus for a second revival to happen. Like the first revival, this one lasted for a good 30 years, then started to peter out. Today, there are very few potters still working at Ohkay Owingeh.

Our Info Sources

Pueblo Indian Pottery, 750 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2000, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.