A Short History of Picuris Pueblo

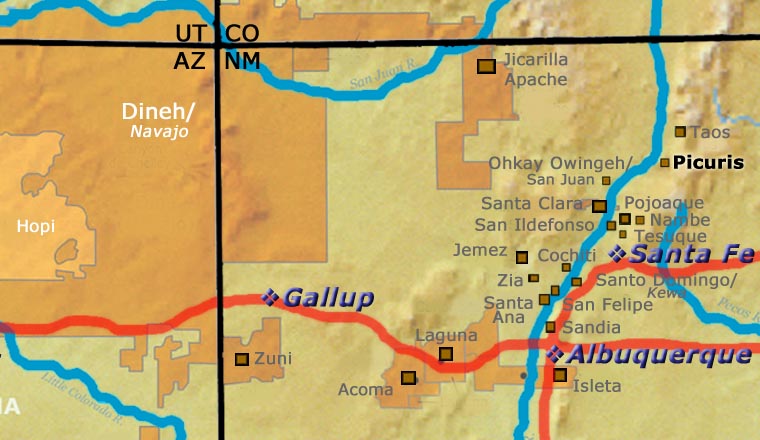

Some of the people who eventually became the Northern Tiwa came down out of the Jemez Mountains and were forced to leapfrog over the Tewa Basin to find arable land. That led them into the area of Taos where they merged with the indigenous (Tano) folks who had built Pot Creek Pueblo. They arrived around the same time the earliest of the Jicarilla Apaches were entering the area.

Pot Creek Pueblo was a melting pot of cultures and reached its height in the early 1300s with about 3,000 residents. Then a fire in the south structure forced the abandonment of the pueblo in 1320 CE. There may have been some sort of schism within the pueblo because the people who eventually became the Pueblo of Picuris left the area of Pot Creek Pueblo and headed southeast. Others went 12 miles northeast, merging into and expanding the Pueblo of Taos (also originally built by Tano people).

Some archaeologists have dated the founding of the original pueblo at Picuris at about 1250 CE. It means the people who later abandoned Pot Creek Pueblo and went southeast already had somewhere to go. And it seems the Tanoan villagers of the existing pueblo welcomed most of the newcomers.

When the Spanish first arrived in northern New Mexico, Picuris Pueblo was larger than Taos. Their village was located about 25 miles southeast of Taos in a high mountain pass. Their prosperity was most likely the result of increased trading possibilities with the Utes, Comanches, Apaches and Kiowas who often ventured through the pass for raiding and trading purposes. It was that kind of traffic that had made Taos great. The Picuris leveraged their location to be greater yet.

On first sight, Spanish explorer Don Juan de Oñaté referred to the village as the "Grande Pueblo de Picuris." Reports from other Spaniards who visited the area in the late 1500s claim the original pueblo structure was as much as nine stories tall with as many as 3,000 residents. Realistically, it was more like four or five stories high and housed maybe 1,500 inhabitants.

Back then Picuris was a large and relatively powerful pueblo. The Spanish arrival was a major threat to their power and lifestyle. The lush valley where they lived was highly coveted by Spanish settlers. The authorities and the priests had their eyes set on finding any gold the tribe may have had hidden. Finding no gold, they essentially enslaved the people. Their situation got so bad under the Franciscan monks that when the time came, Picuris Pueblo played a central bloody role in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Because of that central role, when the Spanish returned to the area in 1694 they looted, burned and leveled the pueblo. Those residents who escaped the devastation and ensuing deportation into enslavement in Mexico scattered, some to nearby pueblos, some over the hills to the Purgatoire and Cimarron River valleys, some as far as to the Cuartelejo villages on the plains of western Kansas and eastern Colorado. Most of them had returned to the Picuris area by 1706 and had begun rebuilding their homes in a new location. But the pueblo's spirit was broken and Picuris has never returned to its former glory. The 2010 census estimated only 68 enrolled members living on the pueblo, only 439 possible enrolled members in the country.

In the center of today's Picuris Pueblo is the San Lorenzo Mission, built in the 1770s. Because of years of water damage, it was feared in the 1980s that the church would collapse soon. The building couldn't be saved and had to be torn down. Tribal members then spent the next eight years using traditional methods to rebuild the church on the existing foundation. The original Picuris Pueblo site (the one destroyed by the Spanish) was excavated in the 1960s and is now a protected archaeological site.

The Cuartelejo villages were part of what is now known as the Dismal River culture. Dismal River sites are spread from Colorado across Kansas and Nebraska into South Dakota. The plains of west Kansas were one stop along the migration routes of the Dineh and Apaches as they made their journeys over the last thousand years to where they are now. The Jicarilla Apaches were close to their relatives in the Cuartelejo villages, attested to by pieces of Jicarilla pottery from New Mexico being found in Dismal River ruins in Colorado, Kansas and Nebraska. It's only natural that if the folks of Picuris needed to find safety, it would be among people who knew of the common danger and who they'd shared history with. It's also interesting that in a couple Dismal River sites, pottery made of local clay in Picuris forms has been found.

Between the Cuartelejo timeline and the early Taos and Picuris timelines is place for time spent in Apishapa culture sites (1050 CE - 1450 CE). The Apishapa culture was centered around the Apishapa River in southeastern Colorado with a northern boundary near Colorado Springs and a southern boundary in the hills and ridges south of the Purgatoire River. For years they were thought to be an offshoot of the Graneros culture in the Texas panhandle area but they've more recently been tied to the older Republican River culture of eastern Colorado/western Kansas. The migration timeline might have been Cuartelejo to Republican River to Apishapa to possibly Taos and Picuris. They left behind significant indications of regular trade between their Apishapa Canyon pueblos and the Northern Tiwa pueblos. The stone ruins they left behind in Colorado and Kansas deteriorated and fell down over time, to be replaced by tipi rings indicating more nomadic peoples had migrated in and taken their place.

The people of Taos and Picuris have old stories about how they came to their present area from somewhere to the north. Their language (Northern Tiwa) has been tied to Kiowa-Tanoan, a family of languages spread from the Rio Grande Valley to eastern Oklahoma. Some of those who'd inhabited Dismal River sites back in the day had migrated east and merged with Kiowa clans in South Dakota. Those clans were then pushed south by population pressure from the east, their neighbors wouldn't let them go west and no one went north. Eventually they separated into the Kiowa and Comanche tribes of Texas and Oklahoma that we know today. In the time of the Spanish occupation, those Kiowas and Comanches were frequent visitors to the trade fairs at Taos, Picuris and Pecos (known as Cicuyé back then). They also came regularly to raid for food and supplies, and to kidnap a few women and children.

In the early 1600s a pair of Franciscan fathers led a group of soldiers over the hills and through the valleys northeast of Taos until they came to the Spanish Peaks in southern Colorado. Supposedly, there were stories circulating among the Tarahumara in northern Mexico of a rich gold mine in the valley between the Wahatoya Mountains (the Wahatoyas are also the Guajatoyas, meaning: Breasts of the Earth, which is what they resemble in profile). Once there the priests went searching for gold and supposedly found a good, easy-to-mine vein on the side of the West Spanish Peak. The priests sent some of the soldiers off to find help and they shortly returned with a number of local Indian captives. Those captives were forced to work the mine and when the priests felt they had enough gold ore in hand, they killed the captives, threw them into the mine and then collapsed the entrance. They loaded their bags of gold ore onto a couple burros and headed west to Cuchara Pass, then south to the gap in the Dakota Wall at Stonewall. None of that group of Spaniards nor their gold survived to leave the Purgatoire Valley. Somewhere south of that gap in the ancient sandstone wall they were set upon by the local folk and wiped out. Bits and pieces of Spanish armor and the bones of a couple burros are rumored to have been found up the valley to the south of Stonewall along the South Fork of the Purgatoire but nothing else has ever turned up. Somehow that story did make it into the Spanish records and a relief expedition was dispatched but to no avail. And the original Spanish name of the river was "Frenchified" into "Purgatoire" (and Anglicized into "Purgatory"): Rio de las Animas Perdido en Purgatorio (River of Souls Lost in Purgatory). This story is where the name came from. The French got involved because the area was great fur trapping country back then. Also, as another story goes, the Sangre de Cristo (Blood of Christ) Mountains were given that name by one of those Franciscan priests after seeing sunset from the mountains' eastern slopes.

Note: Between 1865 and 1867 there were about 200 gold mine claims filed on the sides of the Spanish Peaks. One of Abraham Lincoln's sons owned several on the southeast and east sides of the West Peak, right around the tree line. That's in the valley between the two peaks. The mountain was often deadly (still is) and most discoveries petered out quickly, but a couple were worked for 20 years, then abandoned before being reworked in the 1930s during the Great Depression. The early 1950s saw a massive dredging/placer operation happen just below the tree line around the bottom edges of the mountains' talus slopes but no one has ever declared they found the original Spanish mine again. It took more than 20 years to extinguish all the mining claims on the two mountains before the Spanish Peaks National Wilderness Area could be officially designated by Congress in 2000.

Today, the government of Picuris Pueblo is involved in several commercial ventures, including Sipapu Resort with ski slopes in the mountains a few miles east of the pueblo area itself.

Upper left photo courtesy of Wikipedia userid Davidhc9, CCA-by-SA 3.0 License

About the Pottery of Picuris Pueblo

Picuris and Taos Pueblos (and the Jicarilla Apache) traditionally used a clay that is high in mica content to make their pottery. This micaceous clay creates a distinctive metallic luster that sets their pottery apart from virtually all other pueblo pottery. In addition, micaceous pots and bowls are the only pueblo pottery that can be put directly on a fire or stove for cooking purposes. The Tewa Pueblos to the south sometimes copied the Taos/Picuris style but they used different clays and tempers and achieved different results.

Taos, Picuris and Jicarilla Apache pottery is very similar. The main difference between them is that unpainted functional Picuris pots tend to be thinner than similar Taos or Jicarilla pots. On some of their pots Picuris potters coat the pot with a slip of mica before it is fired. Often the fire clouds produced in the firing process are a pot's only decoration. Sometimes Picuris potters would add raised rope or inlaid beads or molded clay animals to their pots. They also produced an amount of striated pottery, the striations being achieved through various physical means.

In the old days, local Hispanic villagers often purchased Picuris functional pottery for household use. While the unpainted functional micaceous pottery has been in production since about 1600, it really dominated Picuris production after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. In many ways the Picuris potters copied the plain pots of their new Jicarilla Apache neighbors (the Jicarillas arrived in the neighborhood about the same time as the Spanish). Picuris potters produced a fair amount of their traditional pottery styles until their primary source of micaceous clay was almost destroyed by an industrial mica-mining project. Loss of that clay source nearly ended the Picuris pottery tradition.

More recently Anthony Durand took on the job of trying to revive the Picuris pottery tradition after his grandmother led him to a new source of micaceous clay. Sadly, Anthony passed on in 2009. These days, many non-Picuris artists are also using micaceous clay to create beautifully shaped pots, figures and sculptures. Recently there has been a movement among the pueblo potters to create more aesthetic and artistic styles of pottery using micaceous clays. They hope this effort will create a market for their pottery as works of art rather than just functional utility ware.

Our Info Resources

Some of the above info is drawn from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Some has been gleaned from Duane Anderson's All That Glitters: The Emergence of Native American Micaceous Art Pottery in Northern New Mexico, School of American Research Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 1999.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.