Sandia

A Short History of Sandia Pueblo

Sandia Pueblo was founded around 1300 AD in the area between the Sandia Mountains and the Rio Grande. When Francisco Vasquez de Coronado arrived in 1539, he named the pueblo Alameda. The pueblo at the time consisted of more than 3,000 members. Today that population is down to about 500. The people speak Tiwa and trace their lineage back to immigrants coming north from the Aztec areas in central Mexico.

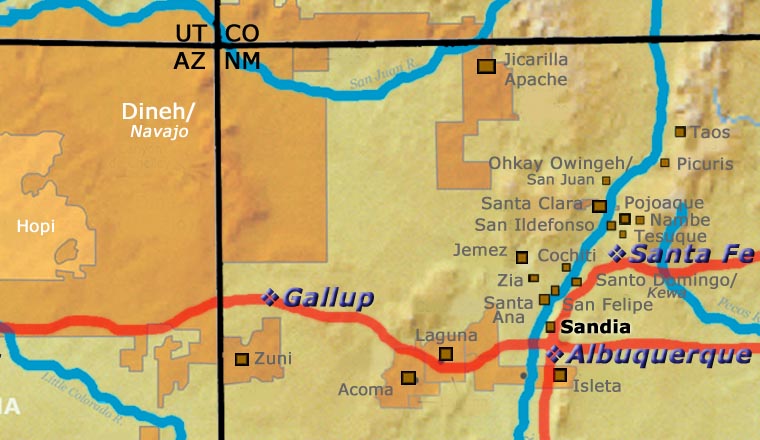

Today's Sandia Pueblo occupies about 22,877 acres of land on the north side of Albuquerque, bounded on the east by the Sandia Mountain foothills and on the north and west by the Rio Grande bosque (a forested area where the tribe gets their firewood and wild game).

Like the other New Mexico pueblos, the Sandias participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Spanish were evicted from the area but returned in 1681. The Sandias fled to the Hopi mesas and Governor Otermin ordered his troops to burn the abandoned pueblo. The Sandias returned shortly after and began to rebuild. The Spanish returned again in 1692 under Don Diego de Vargas and retook Nuevo Mexico. The Sandias ran from de Vargas and took refuge among the Hopi again. While they were gone, de Vargas had their main village burned again.

In the land of the Hopi, the Sandias and a few Isletans with them were given space on a northern finger of Second Mesa to build a new pueblo. They built Payupki, a small pueblo they occupied for about 60 years. The potters of Payupki were prolific and some of the designs they left behind were picked up and re-used by Nampeyo of Hano 200 years later. Then in 1740 a small contingent of Franciscan padres arrived and began trying to talk the Sandias into returning to New Mexico. They were promised a lot but very little was delivered on their return to the Albuquerque area. And their pottery has not again achieved the excellence of the work they left behind at Payupki.

By 1742, 441 Sandias had returned to the area of their old pueblo but they weren't allowed to rebuild until they got a Franciscan father to intercede for them in 1747. Then they were forced to build in a location where they were wide open to Comanche and Apache raids and they had little means of protection.

In 1762 Governor Tomas Capuchin ordered the pueblo be rebuilt properly as a better buffer between the Spanish settlement at Albuquerque and those raiders coming from the north. The Governor also thought offering housing to the Hopis who accompanied the Sandias might be helpful in furthering the cause of the Spanish among the Hopis in Arizona but it didn't work out that way. The Hopis at Sandia were segregated from the Sandias and housed in the outer sections of the pueblo where they bore the brunt of the worst raids. Finally Governor Juan Bautista de Anza led a force north that wiped out the entire Comanche command structure at the Battle of Cuerno Verde in 1776. That finally forced the Comanches to sue for peace. That peace held until the Americans arrived in the 1840s.

Over the years Sandia's population declined from 441 in 1742 to 350 in 1748 to 74 in 1900. After the Spanish Flu pandemic passed in 1918 the tribe's population finally began to grow again but it may never reach the population of the years before the Spanish first arrived.

Today, Sandia Pueblo owns and operates several businesses, including Sandia Resort and Casino, Sandia Lakes Recreation Area, Bobcat Ranch and the Bien Mur Indian Market. However, the younger generations are less and less interested in learning Tiwa and aren't much interested in continuing with many other tribal traditions. John Montoya, the only well-known modern Sandia potter passed away on New Year's Eve at the end of 2004 and no one has, of yet, taken his place.

Photo courtesy of Amber Flores Jordan

The Pottery of Sandia Pueblo

Once upon a time potters from Sandia Pueblo were known for the quality and beauty of their pottery. At the time, though, they were hiding out on Second Mesa in northeastern Arizona after the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. The Hopis had given them land on the north end of Second Mesa and the Sandias built a village named Payupki.

The downfall began around 1740 CE. That's when the Franciscan fathers convinced the Sandias to return to their former homes near Sandia from Payupki. Big promises were made but none were ever kept. The trials and tribulations the Spanish authorities visited on them when they returned to the Albuquerque essentially ended all possibility of a pottery tradition. There may not be a single Sandia potter working today.

Many of the decorations the Sandias painted on their pottery at Payupki are still in use by potters from other pueblos. One of the more famous of those potters was Nampeyo of Hano. It has been conjectured that some of those designs were picked up by the Sandias in their journey from the Rio Grande Valley to Tusayan, passing through Acoma, Laguna, Zuni and Jornada Mogollon territory on the way.

In those days, people traveled from watering hole to watering hole and might stop somewhere for a few days or a few months before moving on. Especially pregnant women and their families, and ritual specialists. That's how cultural cross-pollination happened. That's how new clans became established in different pueblos. That's how innovations in technology and design traveled cross-country. At Payupki a whole cascade of those came together.

The village of Sikyatki was destroyed around 1625. First Mesa was being disturbed regularly until after Awatovi was destroyed in 1701. The whole Hopi area was afraid of a coming Spanish intervention that never really materialized, until the Americans arrived around 1850.

When the Sandias arrived in the Hopi region in the early 1680s and explained their situation to the Hopis, they were given land on Second Mesa. Those Spanish who did make the trek to Hopiland after 1700 were generally Franciscan fathers. The only place in all of Hopiland where their message gained a foothold was Payupki. That message then led them into disaster for the next couple decades.

Today, there may be one or two potters doing a bit of work at Sandia but there's no one producing commercially. The last was John Montoya, but he passed on in 2005.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.