Santo Domingo

A Short History of Santo Domingo Pueblo

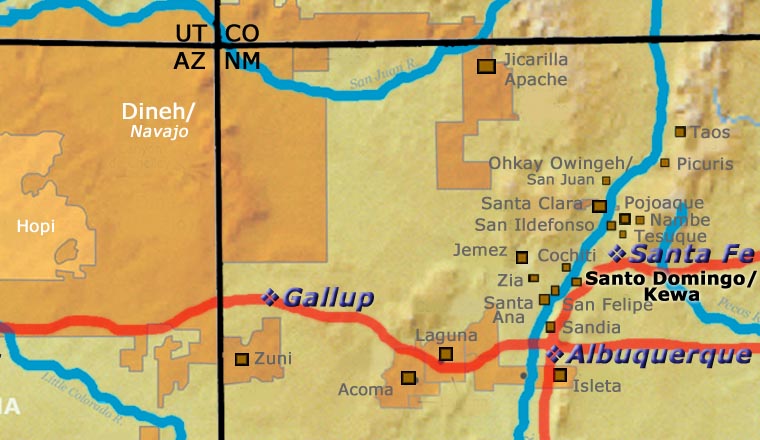

Santo Domingo Pueblo is located on the east bank of the Rio Grande about half-way between Santa Fe and Albuquerque. Historically, the people of Santo Domingo were among the most active of Pueblo traders. The pueblo also has a reputation of being ultra traditional, probably due, at least in part, to the longevity of the pueblo's pottery styles. Some of today's popular designs have changed very little since the 1700's.

In pre-Columbian times, traders from Santo Domingo were trading turquoise (from mines in the Cerrillos Hills) and hand-made heishe beads as far away as central Mexico. Many artisans in the pueblo still work in the old ways and produce wonderful silver and turquoise jewelry and heishe decorations.

Like the people of nearby San Felipe and Cochiti, the people of Santo Domingo speak Keres and trace their ancestry back to villages established in the Pajarito Plateau area in the 1400s. Like the other Rio Grande pueblos, Santo Domingo rose up against the Spanish oppressors in 1680, following Alonzo Catiti as he led the Keres-speaking pueblos and worked with Popé (of San Juan Pueblo) to stop the Spanish atrocities. However, when Spanish Governor Antonio Otermin returned to the area in 1681, he found Santo Domingo deserted and ordered it burned. The pueblo residents had fled to a nearby mountain stronghold and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to Nuevo Mexico in 1692, he attacked that mountain fortress and burned it, too. Catiti died in that battle and Keres opposition to the Spanish crumbled with his death. The survivors of that battle fled, some to Acoma, some to fledgling Laguna, some to the Hopi mesas. Over time most of them returned to Santo Domingo.

In the late 1690s, Santo Domingo accepted an influx of refugees from the Galisteo Basin area as they fled drought and the near-constant attacks of Apache, Comanche, Ute and Navajo raiders in that area.

Today's main Santo Domingo village was founded about 1886.

In 1598 Santo Domingo was the site of the first gathering of 38 pueblo governors by Don Juan de Oñaté. He attempted to force them to swear allegiance to the crown of Spain. Today, the All Indian Pueblo Council (consisting of the nineteen remaining pueblo's governors and an executive staff) gathers at Santo Domingo for their first meeting every year, to continue what is now the oldest annual political gathering in America. During the time of the Spanish occupation, Santo Domingo served as the headquarters of the Franciscan missionaries in New Mexico and religious trials were held there during the Spanish Inquisition.

Today, the people of Santo Domingo number around 4,500 with about two-thirds of them living on the reservation.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About the Pottery of Santo Domingo Pueblo

There was a time when potters in villages in the Galisteo Basin were using lead ores from the Cerrillos Hills to make glazed pottery. Samples of that pottery have been found all over the Southwest. Production of it stopped, though, when the Spanish took control of the Cerrillos lead mines around 1696.

With that end to their one valuable item for trade, many of those people in the Galisteo Basin moved illegally (according to the Spanish) downhill to Santo Domingo and merged into that pueblo. However, all Puebloan pottery production took a severe hit in those years. The potters scrambled to develop shapes and forms to sell to incoming colonists but with the added demands of the Spanish authorities and the church, the quality of the pottery fell way off.

Pottery production at Santo Domingo didn't pick up again until the mid-1800s, after the Americans arrived. It was in the 1880s that the Santa Fe Railroad snaked its way south along the Rio Grande and across Santo Domingo land. The pottery traditions of the pueblo almost died out after that and many Santo Domingos went to work laying tracks. Even today many Santo Domingo men work as wildland firefighters for the US Forest Service in fire season and ply their artistic talents during the rest of the year. Then in the 1930s the original Route 66 Mother Road ran across Santo Domingo, until that route was realigned further south in 1937. That realignment took most of the tourist traffic away.

The Santo Domingo pottery tradition almost died out again in the 1940s and 1950s. Some of today's potters still tell stories of going out with their grandmothers and aunts to sell pottery on the side of the highway. Times were hard and the return was often not worth the effort. Pottery production dwindled away to just what was needed for ceremonial purposes.

Then Robert Tenorio almost single-handedly resurrected pottery making at Santo Domingo. Santo Domingo clay is thick enough to be carved but is almost always painted instead. The design vocabulary is limited essentially to birds, fish, plants and bold geometrics. Robert brought a new touch to traditional Santo Domingo styles and earned acclaim almost immediately. Then he taught his brothers and sisters and anyone else who would sit still long enough. As he and his students got older and stopped producing, along came younger potters who are, in turn, teaching younger students. His influence can be found among many of today's Santo Domingo potters, even if they say he stimulated them to learn on their own.

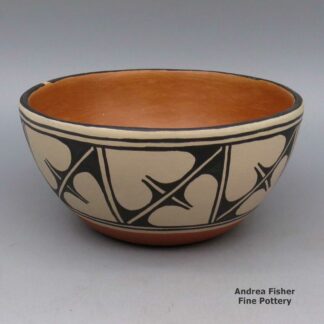

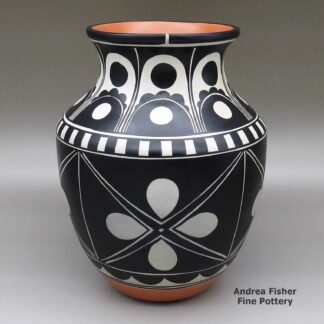

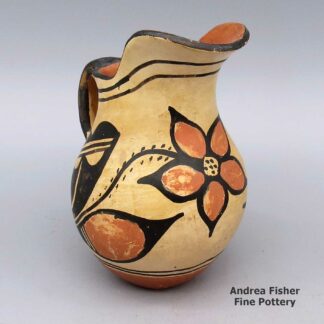

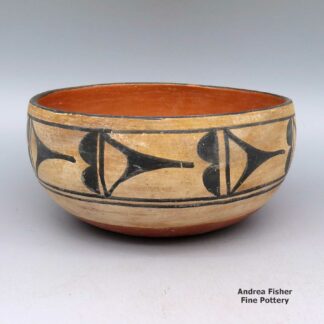

While today's Santo Domingo pottery is known for designs often described as simple geometrics, an outstanding feature of those designs is their boldness: the lines are thick and well-defined.

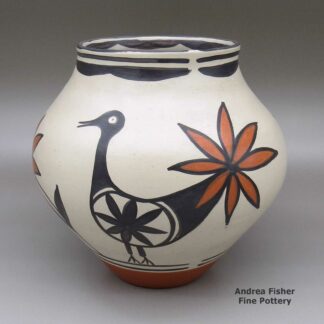

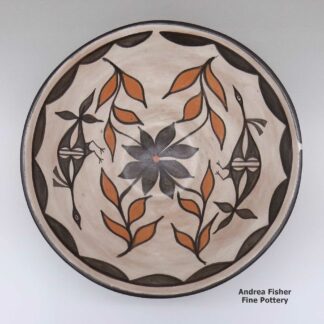

Religious leaders forbid the representation of human figures as well as other sacred designs on pottery made for commercial purposes. Birds, fish and flowers are common Santo Domingo design motifs. Depictions of mammals are rarely seen. Another typical Santo Domingo style is to paint in the negative, meaning cover the pot in panels of big swatches of black and red so that only a few lines of the cream slip show through.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.

Showing 1–12 of 15 results

-

Alvina Garcia, btsd2l257: Polychrome bowl with geometric design

$250.00 Add to cart -

Ambrose Atencio, aasd2f201, Jar with bird, flower and geometric design

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

Ambrose Atencio, mgsd3c010, Bowl with a traditional Santo Domingo design

$795.00 Add to cart -

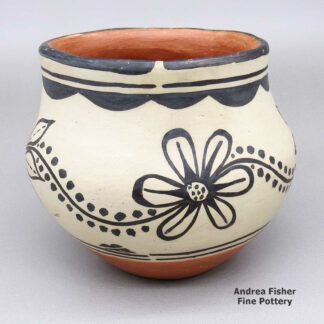

Crucita Melchor, dksd3c251, Bowl with flower and geometric design

$325.00 Add to cart -

Thomas Tenorio, zzsd2l252: Polychrome jar with geometric design

$3,400.00 Add to cart -

Thomas Tenorio, zzsd3b230, Large polychrome jar with a geometric design

$2,950.00 Add to cart -

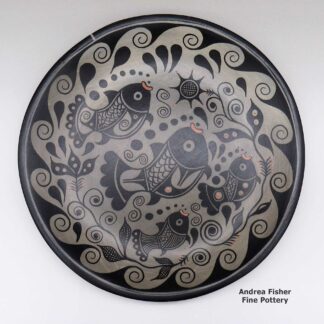

Thomas Tenorio, zzsd3b231, Plate with geometric design

$850.00 Add to cart -

Thomas Tenorio, zzsd3c060, Polychrome cylinder with a geometric design

$2,750.00 Add to cart -

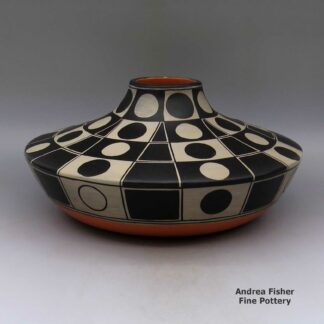

Thomas Tenorio, zzsd3c062m2, Polychrome bowl with a geometric design

$1,550.00 Add to cart -

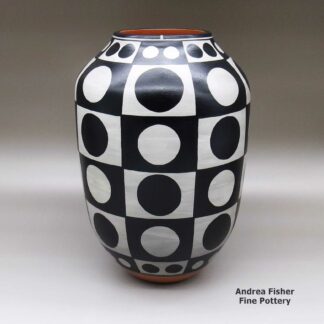

Thomas Tenorio, zzsd3c161, Polychrome jar with a geometric design

$2,400.00 Add to cart -

Unknown Santo Domingo Artist, nusd2m064, Polychrome pitcher with flower and geometric design

$150.00 Add to cart -

Unknown Santo Domingo Artist, rssd2k205, Polychrome bowl with a geometric design

$295.00 Add to cart

Showing 1–12 of 15 results