Zuni

A Short History of Zuni Pueblo

"K'ynánas'tipe stretched his legs to the four great seas, then gradually he settled down and called out, 'where my heart and navel rest, beneath them mark the spot and build your town there for that shall be the midmost place of Mother Earth.' As he squatted over the middle of the plain and the valley Zuni, he drew in his legs and his feet marked the trails leading outward like the radiating web of a spider. The fathers of the people built on this spot and rested their fetishes there." - Frank H. Cushing, Outlines of Zuni Creation Myths, pp. 428-9

Archaeologists have dated some sites on the Zuni Reservation back to the Paleo-Indian Period, more than 4,500 years ago. During the Archaic Period (2,500 BCE to 0 CE), the forebears of the Zuni were hunter-gatherers and just beginning to develop agriculture. The Basketmaker Period (0 CE to 700 CE) saw agriculture become more developed and the Zunis make their first pottery. The Pueblo I Period (700 CE to 1100 CE) saw an expansion of the population and larger settlements were built in the Zuni River area along with the development of the first painted Zuni pottery.

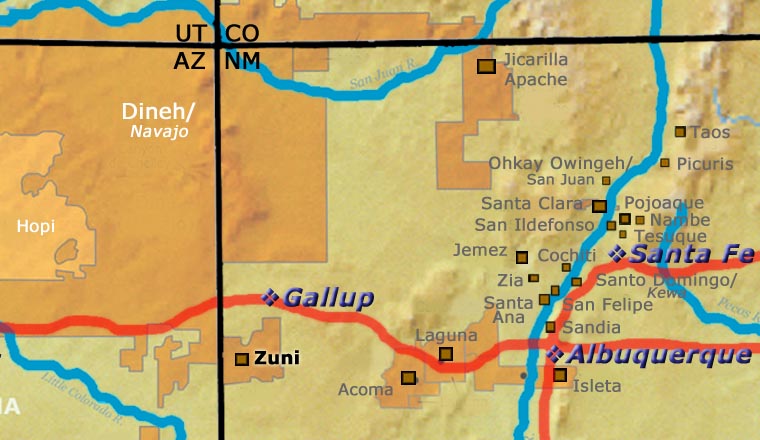

The Pueblo III Period (from 1100 to 1300 CE) saw further population growth in the Zuni River area and a shift from small houses to larger, plaza-oriented villages. The Pueblo IV Period (1300 to 1500 CE) was the time of significant bad weather, great drought and the beginning of the flood of Athabascans and Utes. Many tribal groups were forced out of the Four Corners area and relocated to locations near the Rio Grande, Rio Puerco, Zuni River and Little Colorado River. The main Zuni Pueblo was founded during this time but there were several other large villages in the area, too.

In 1540 Francisco Vasquez de Coronado arrived at the gates of Hawikuh, at the time one of the larger of seven Zuni pueblos. He first approached the pueblo at the end of a four-day religious festival. The Zuni chief had spilled a line of corn meal across the ground before the entrance to the pueblo, meant to signify to the Spanish that they shouldn't cross the line and enter the village yet. Coronado interpreted that line of corn meal as an act of war and immediately ordered his soldiers to attack.

Coronado was almost killed in the fighting (Zuni warriors had dropped a large rock on him, knocking him off his ladder and almost crushing him) but his soldiers did finally win the battle. As Coronado and his men brought horses and sheep with them, they were probably the first such livestock the Zunis had ever seen. The gold the Spaniards were looking for: it turned out to be Sikyátki Polychrome bowls and jars, yellow clay gifts from the Hopi people to the Zuni people.

The Zuni chief did give Coronado a refugee from the Plains tribes, someone who'd somehow made his way as a lone traveler to Hawikuh. That refugee was supposed to be a guide for Coronado and his men but he was instructed by the Zuni chief to take Coronado into the Plains and get him lost there. When Coronado finally realized that, more than a year later, he ordered the guide executed, then turned his men around and headed back to Zuni and Mexico.

When he passed by Zuni in 1542, Coronado left three Mexican Indians behind with the tribe. They most likely informed the tribal leaders of the extent of the Spanish domain in Mexico and the power they exercised there.

Except for a couple passing exploratory expeditions, the Zuni pueblos were left alone until the 1620s. Then came the friars who oversaw the construction of a mission church at Hawikuh in 1629. At first the Zuni people were friendly with the priests but with the forced labor requirements and forced religious conversions, the priests wore that welcome out quickly. Relations had changed drastically for the worse by the time of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Zuni warriors killed the priests and burned the missions but they preserved the relics and icons the priests had brought from Spain.

The tribe built a village near their fortress atop Dowa Yalanne and prepared to defend their people and way of life against the Spanish army. When Don Diego de Vargas arrived with troops in 1692, he attacked the fortress twice and failed. Then he negotiated with the Zuni war chief and was allowed to ascend to the top of Dowa Yalanne. He was given a tour of the property and he found many relics from the destroyed missions there. With that knowledge, he arranged a peace between the Spanish and the tribe. Between 1693 and 1700 the tribe consolidated all their small villages into what is now the Pueblo of Zuni.

Photo courtesy of Ken Lund, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License 2.0 Generic

About the Pottery of Zuni Pueblo

The Zuni people have a long pottery tradition, going back more than a thousand years. Because they've lived in their locations along the Zuni River for so long, cross-pollination with other tribes has occurred often. The Zunis have deep connections with the Hopi, the Acomas, the Lagunas and others. Techniques and designs from the Rio Salado area, the Little Colorado area and the Mimbres and Jornada Mogollon areas have become part of the Zuni tradition. But when the Americans arrived, they brought cheap, enameled cookware and metal utensils with them. Zuni pottery production quickly went off a cliff.

In the 1880s and 1890s, the Zuni area was plundered by "ethnologists" and "archaeologists" claiming to be preserving the Zuni heritage. As in most pueblos that suffered a similar influx of "ethnologists" and "archaeologists," so much material was removed that their cultures were almost stripped bare and they were left with almost nothing of historic import. The primary potter at Zuni in this time was We'wha, a two-spirit man. It is said that We'wha taught Arroh'ah'och from Laguna Pueblo his methods of creating a pot, painting it and then firing it. Arroh'ah'och went back to Laguna and made a historic series of jars before he died. We'wha had already passed by then and the quality and quantity of Zuni traditional pottery hit rock bottom.

The railroads arrived in New Mexico in the 1880s and right behind them came the first Anglo traders. Over the next 50 years Zuni pottery turned more and more to what the traders wanted. With the push into mass production, the quality fell off. The end result was the value of Zuni pottery fell way off and the potters tired of what they were doing. Pottery making dropped off in the 1940s until only ceremonial vessels were being made. Things got a bit better when potters from other pueblos began opening up the general market for Southwestern products and art but Zuni is well off the beaten path, in more ways than one.

By the 1940s the Zuni pottery tradition was just barely hanging on. Pottery for ceremonial use was being made but not much else. Catalina Zunie started teaching ceramics courses at Zuni High School in the late 1950s. She passed the torch to Daisy Hooee in 1960 and Daisy taught at the high school until 1972. When Daisy retired Jennie Laate took over teaching the class. After Jennie came Noreen Simplicio, then Gabriel Paloma.

Many of today's Zuni potters learned their craft at school. That method of learning has also helped them bridge the gap between traditional and contemporary. It also means that many of today's Zuni potters have never ground-fired their pottery as they learned to use a kiln at the high school.

Other of today's Zuni potters grew up in families where someone was making pottery the old way, with no kiln involved. The Nahohai and Bica families are in this group. Their skills were passed down more organically: mother and grandmother to daughters.

Josephine Nahohai said she learned from her mother and her aunt, Myra Eriacho. She once asked Daisy Hooee how to make ground hematite adhere better to the clay. Daisy told her to add sugar to the mix. That didn't work. She finally found the answer she needed from Ethel Youvella, a friend of hers from the years spent at the Albuquerque Indian School. In 1986, Josephine and several members of her family went to Washington, DC to participate in a Smithsonian craft fair. While they were there, they also went into the museums around the city and copied designs from virtually every ancient Zuni piece they found (most were hidden in the basements).

Zuni clay is rather sandy and doesn't polish to a high sheen. Their base clay is reddish and many potters cover that with several coats of white slip to give them a different canvas to paint on. Many of their designs have ancient roots and are unique to Zuni. Other designs with ancient roots are common to other pueblos. The Zunis also have ancient stories that are very similar to stories told in the Rio Grande Valley and on the the Hopi mesas. In some of their stories, the events and roles are reversed.

Zuni is also in a location where influences from different prehistoric cultures overlapped. Those influences are easily seen in the pottery history. Zuni has also played host to cohorts from other tribes in times of drought, disease and societal unrest. That has contributed to the general cross-pollination of ideas and designs and the dissemination of new techniques throughout the Pueblo world.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.

Showing 1–12 of 34 results

-

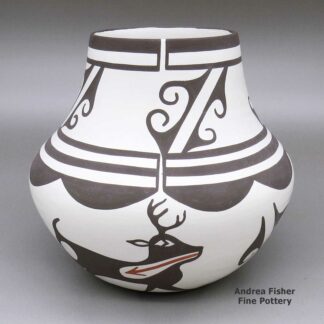

Agnes Peynetsa, ppzu3c030, Jar with deer-with-heart-line and geometric design

$625.00 Add to cart -

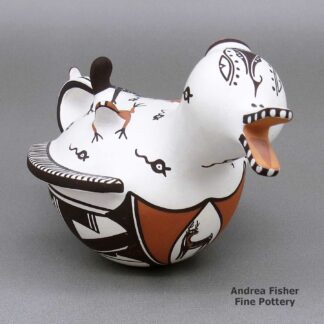

Agnes Peynetsa, zzzu3b515, Duck pot with a deer with heart line design

$395.00 Add to cart -

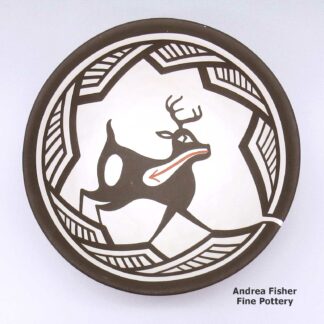

Alan Lasiloo, zzzu3b516, Bowl with deer-with-heart-line design

$350.00 Add to cart -

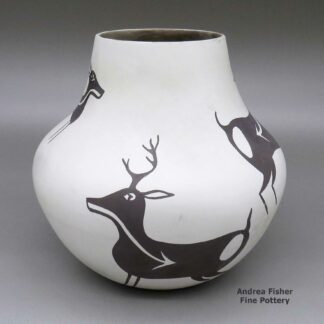

Alan Lasiloo, zzzu3b517, Jar with a deer-with-heart-line design

$795.00 Add to cart -

Alan Lasiloo, zzzu3b518, Jar with deer-with-heart-line design

$650.00 Add to cart -

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu2m052, Polychrome jar with bird, fine line, and geometric design

$1,800.00 Add to cart -

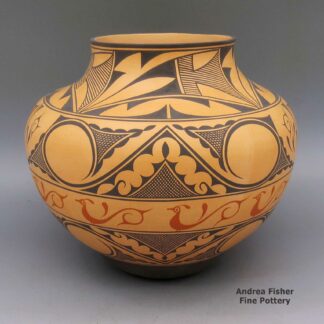

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu2m140, Polychrome jar with medallion, bird and geometric design

$2,600.00 Add to cart -

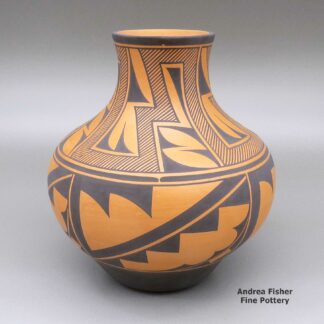

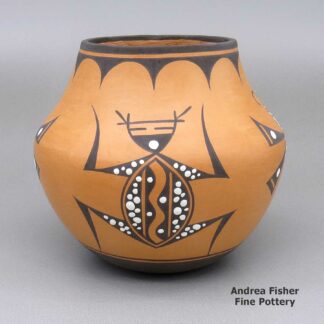

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3a301, Red and black jar with a geometric design

$850.00 Add to cart -

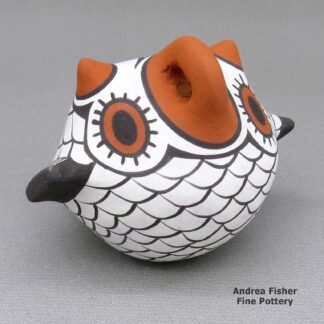

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3b072m1, Small polychrome owl figure

$165.00 Add to cart -

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3b072m2, Small polychrome owl figure

$165.00 Add to cart -

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3b073, Polychrome jar with a frog, dragonfly, and geometric design

$275.00 Add to cart -

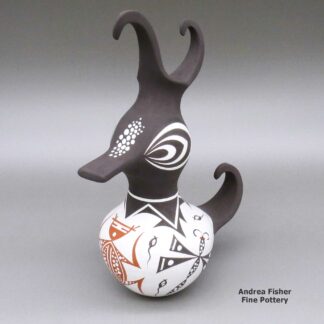

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3c030m1, Duck jar with geometric design

$850.00 Add to cart

Showing 1–12 of 34 results