San Felipe

A Short History of San Felipe Pueblo

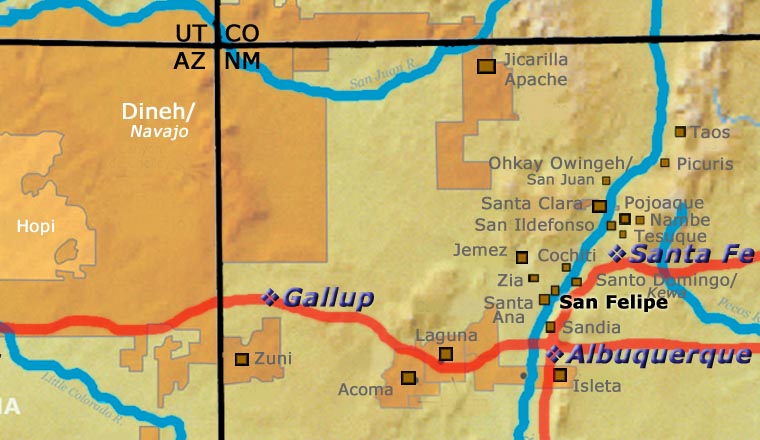

During the great migrations from the Four Corners area to what are now the Rio Grande Pueblos, the people of Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe were one. Before descending off the Pajarito Plateau to the Rio Grande, they settled in the area now known as Bandelier National Monument, taking advantage of a volcanic ash landscape that made it easy to construct dwellings. However, over time that area got too dry, too, and the people decided to move closer to the large river. Disagreements over where to settle split the people into what are now the Cochiti, Santo Domingo and San Felipe Pueblos.

When Francisco de Coronado arrived in 1540, there were two San Felipe villages, one on either side of the Rio Grande. The main villages were comprised of large two-and-three-story structures plus a couple hundred outlying dwellings. Coronado didn't stay long, there was no gold to be had. He and his men quickly moved on to Pecos Pueblo.

San Felipe was left alone until Don Juan de Oñaté came north in 1598. Then the troubles began. The Spanish built their first mission church next to the east village around 1600. It was built with conscript Indian labor and paid for by taxes extracted from the village. As more Spanish settlers moved into the area, that situation got worse.

The people of San Felipe participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 but killed no Spaniards or any priests. Governor Otermin returned with troops in 1681 and found San Felipe abandoned as the people had hidden themselves atop nearby Horn Mesa. The Spaniards looted and burned the pueblo before returning to Mexico. When Don Diego de Vargas came back in 1692, the people chose to surrender and be baptized rather than fight. To test the peace they first settled atop nearby Santa Ana Mesa. A few years later they descended into the Rio Grande Valley and founded today's pueblo.

The Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad built their main line along the Rio Grande, crossing Santo Domingo, San Felipe, Santa Ana, Sandia and Isleta land before reaching the Belen Cutoff area in the 1880s. Stations were built along the line next to each of those pueblos. That would have brought tourists to San Felipe but that was discouraged by the elders and there wasn't much to see anyway. Today's AmTrak and New Mexico RailRunner follow some of those same tracks.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

About the Pottery of San Felipe Pueblo

San Felipe has always had more arable land than most of the other pueblos and is still known for its agricultural products, although most people commute to work off-pueblo. The long-held isolationism of the San Felipe people has contributed to the loss of many traditional activities, including the making of pottery. The San Felipe pottery tradition was interrupted in the aftermath of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt and it never really got started again. Prior to the revolt the people of San Felipe, Santo Domingo and Cochiti were using lead ores mined in the nearby Cerrillos Hills to make a paint that fired to a thin glaze on their pots. After the Spanish returned to the area in the mid 1690s, they made the lead mines off-limits to the people, saving the lead to make bullets for themselves. There was some grayware made at San Felipe after that but most pottery in the pueblo came from Santo Domingo or from Zia.

San Felipe's potters never really recovered from that. Potters from other pueblos have married in over the years and have been able to carry on making ceremonial pottery but an actual, recognized, San Felipe pottery tradition has not survived.

In the 1920s the Mother Road, Route 66, was stitched together across the continent out of already existing roads. Until the realignment in 1937, Route 66 also ran along the Rio Grande from Santa Fe to Albuquerque before turning west over West Mesa and heading for Los Angeles. The stretch of road across the various pueblos was dirt and gravel for years before being paved. All the pueblos crossed by that road had stands by the roadside where many a pueblo potter would display her wares and wait for someone to stop and buy something. Not so much at San Felipe: almost no one was making pottery, never mind pottery-for-sale.

Most San Felipe potters active today either learned the art on their own or learned from artisans at other pueblos. On their return to San Felipe they discovered there is no living tradition of San Felipe designs. The revival of San Felipe pottery tradition is further complicated by the fact so few people remember where good clay might be found on pueblo lands. So they have been somewhat free to develop their own designs, as long as they don't cross any religious boundaries.

Our Info Sources

Southern Pueblo Pottery, 2000 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2002, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from old newspaper and magazine clippings, personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.

Showing all 3 results

-

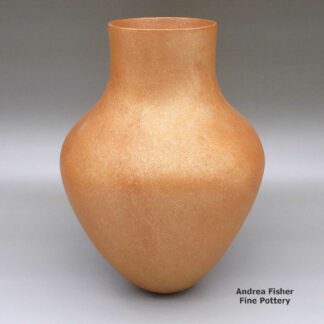

Hubert Candelario, thsf3b023, Golden micaceous jar

$1,995.00 Add to cart -

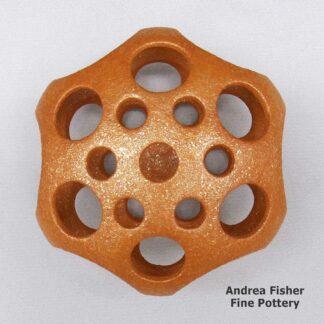

Hubert Candelario, zzsf3c240, Micaceous gold holey pot with cut-outs

$2,200.00 Add to cart -

Pauline Latoma, plsf2k122, Plate with sun face medallion and geometric design

$175.00 Add to cart

Showing all 3 results