About Hopi Pottery

About the Pottery of the Hopi People

Pottery was being made in the area of the Hopi mesas before migrants from the central Mexico area first arrived in the 600s CE. Those migrants, though, they brought a much better ceramic technology with them. They also brought a whole new design vocabulary, architectural advancements, more defined rituals and better seeds with other agricultural advancements. They spread out across the Southwest between the Virgin River and the Rio Grande, from the Chihuahua and Sonora deserts north to the Great Salt Lake, and they multiplied. The weather of this new countryside was very fickle, though, and they had to learn how to store food and keep it good for years. The best tool for that was pottery. Then they learned to decorate their pottery with their prayers for the seed within, and for the survival of their people.

For hundreds of years those designs were repetitive geometrics, in black-on-white or gray-white bisques, most matte but more and more polished as time went on. Then, from the south again, figures in black-on-white were introduced. Then came figures and designs in red-and-black-on-white. Then came figures and designs in various combinations of red, black and white on various backgrounds. Each step in the development of decorative and color schemes is reflective of experiential religious developments within one clan or another, one pueblo or another. While a lot of what flowered into Sikyátki style and design was developed in bits and pieces along the rim of Antelope Mesa, it took the experience of Sikyátki to put it all together. Just as the design palette of Sikyátki reached its peak, the village's chief determined they had strayed too far from the traditionally conservative Hopi path and they needed to be put to death for it. He arranged with the elders of Walpi and other villages to have the deed done and sometime in 1625 it was completed: everyone was killed except for a few ritual specialists saved for their spiritual value.

The styles and designs of Sikyátki lived on on some Awatovi pottery for a few years but the entire design palette changed after the Spanish arrived in 1629. San Bernardo Polychrome came into production almost immediately with the reduction in labor force as so many of the Awatovis were forced to build a mission first, then serve it thereafter. The design palette changed, too, when all the kachina designs were forced out by the Franciscan priests. Almost everything changed again with the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. There was a general return to themes prevalent before the Spanish arrived across the entire Southwest, except by then most potters were firing their pots using sheep, cow or horse manure. Around the Hopi mesas, a merging of designs and supernaturals with the layouts from the San Bernardo and Sikyatki pahses happened. Some archaeologists have termed the pottery that was produced for 100 years after the Pueblo Revolt as "Payupki phase." It faded out around 1780, about the same time the last of the Tiwas and Keresans returned to the Rio Grande Valley from the village of Payupki on Second Mesa. After that came the phases of Polacca Polychrome, including the white-slipped years after the times of drought and disease in the 1800s that were spent at Zuni.

By the mid-1800s, Hopi pottery tradition had been almost completely abandoned, its utilitarian purposes taken over by cheap enamelware brought in by Anglo traders. Hopi pottery production sputtered along until the 1880s when one woman, Nampeyo of Hano, almost single-handedly revived it. Nampeyo lived in Hano on First Mesa and was inspired by pot sherds found among the nearby ruins of the ancient village of Sikyátki. Like all the other potters around First Mesa at the time, Nampeyo was producing jars, bowls and canteens, often with one surface slipped white and decorated with designs in black-and/or-red. At the urging of Anglo traders' Alexander Stephen and Thomas Varker Keam, she began experimenting with polishing the surface of pieces coiled entirely of Jeddito yellow clay and then painting her designs directly on that. Today credit is given to Nampeyo for fully reviving the Sikyátki style. She was so good that Jesse Walter Fewkes, the first archaeologist to formally excavate Sikyátki, was concerned that her creations would shortly become confused with those made hundreds of years previously.

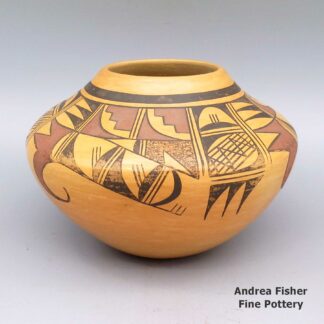

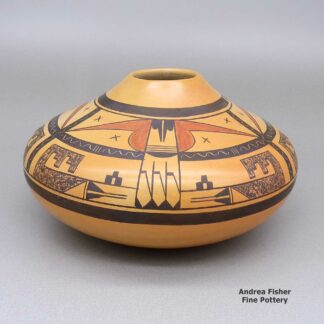

Sikyátki pottery shapes are very distinctive: flattened jars with wide shoulders; low, open serving bowls decorated inside; seed jars with small openings and flat tops; painting methods of splattering and stippling and very distinctive designs. The Sikyátki style seems to have evolved as various Zuni-, Keres- and Towa-speaking potters came together with Water Clan potters from the Hohokam areas of southern Arizona and northern Mexico, and they began working with clays found in the nearby Jeddito valley area. Over the years, other clans came to the area and made their own contributions to what we now refer to as "Sikyátki Polychrome." According to Jesse Walter Fewkes, that merging of styles, techniques and designs created some of the finest ceramics ever produced in prehistoric North America.

Today's Hopi Pottery

Most Hopi pottery is unmistakable in its shapes, colors and designs. The Hopis are blessed with multiple excellent clay sources, each offering a different deep color after polishing and firing. Most Hopi pottery uses a buff, red, white or yellow clay body. Some kachina carvers make pottery and sometimes carve and etch their surfaces. Most Hopi potters, though, form their pieces and paint their decorations using colors derived from boiled-down plants, watered-down clay and from crushed minerals.

Much of the symbology painted on Hopi pottery is themed with "bird elements:" eagle and parrot tails, feathers, beaks and wings, and with katsinam and permutations of migration patterns. Many Hopi, Hopi-Tewa and Tewa potters are members of the Corn Clan and their annual religious cycle revolves around the seasons of corn. The vast majority of today's Hopi pottery shapes and the designs painted on them are obvious descendants of the work of potters who existed 200-and-more years ago.

The above paragraph applies mostly to potters from the vicinity of First Mesa. The few potters from Second and Third Mesas seem to derive their design palettes from farther back in time, to the geometric designs, patterns and figures of the rock art prevalent before the advent of the katsinam, and the emergence of the Medicine, Sacred Clown and Warrior societies 800 years ago.

Showing all 2 results

-

Dawn Navasie, esho2g068, Jar with geometric design

$450.00 Add to cart -

Gloria Mahle, roho3d143, Jar with geometric design

$750.00 Add to cart

Showing all 2 results