Kokopelli

Hohokam, Ancestral Puebloan, Mimbres, Dineh, Hopi, Zuni

The Flute Player's Names:

Kokopelli, Kokopele, Kokopeltiyo, Kokopilau - Hopi

Kokopelli-mana, Kokopelmana (Kokopelli's wife) - Hopi, from Hohokam

Neopkwai'i - at Sichomovi

Ololowishkaya - Zuni

Kokopelli is from the Hopi kokopilau, meaning "the humpbacked flute player," a mythical Hopi symbol of fertility, replenishment, music, dance and mischief. He's easily distinguished by his dancing pose, his hunchback and his flute. Of all the rock art found throughout the desert, canyons, mountains and plains of the Southwestern states, Kokopelli is the only anthropomorphic petroglyph that has a name, an identity and a gender (he even has a named wife, although she is much less known).

The flute player symbol dates back more than 3,000 years to when the first petroglyphs were being carved on a rock face. His image can be found all over the southwestern states, wherever ancient people gathered to "carve their initials" in the rock: Kokopelli was kind of like the "Kilroy was here" of the ancients. He was known from the deserts of California east to the forested land of the Winnebagos (who thought he was so fertile he could "have his way" with any women bathing in the river downstream of him), and from the Fremont people of central and eastern Utah south to the Mayan cities of southern Mexico and Guatemala.

There is also a train of thought that the name Kokopelli may derive from the Hopi "Koko" (for a god) and Zuni "pelli" (for the desert robber fly). The fly also has a humped back and is known for stealing the larvae of other flies. The fly also has a prominent proboscis. Some of the earliest petroglyphs of Kokopelli look more like the fly than a human.

In southern Utah, Kokopelli is remembered as a little man who traveled among the villages with a bag of corn on his back, teaching villagers to plant and care for it as he traveled. Some stories say he stopped and traded corn, beads and seashells for pieces of turquoise. In some Puebloan stories he carried seeds, babies and blankets to give to any maidens he seduced along the way. The Dineh said his hump was made of clouds filled with seeds and rainbows, and when he appeared he brought abundant rain and food for the people. The Zuni thought of him as a "Rain Priest" who could make it rain at will. According to the San Ildefonso people, he's a wandering minstrel, trading new songs for old ones. Anyone who stops to listen to his flute is rewarded with good luck and prosperity. In Old Oraibi, the people believed he carried deer skin shirts and mocassins which he traded for some time with a young woman or for babies that he'd leave with other young women. At Sichomovi, Kokopelli and his wife are painted black, a reminder of Esteban the Moor. (Esteban was a large Moorish slave who had been left at Zuni by Coronado when Coronado left Zuni and headed south to Mexico. Esteban's aggressive interest in Zuni maidens got him killed shortly thereafter, but the memory lingers on among Zuni clans who settled in the First Mesa area in the early 1600s.)

For some people, the Flute Player was a magician, to others he was a storyteller, healer, teacher, trader, trickster or god of the harvest and human fertility. Barren wives sought him out while unwed maidens ran from him in terror. Almost everywhere the Kokopelli symbol was known, he was a welcome figure as an appearance by the Flute Player was a sign of coming good rains, a good harvest and abundant times. He embodied everything wonderful and spiritual about music. He and his flute spread good will, gifts and cheer to everyone he visited. It is said that when his flute began to play, the snow melted, the sun came out, birds began to sing, the grass turned green and all the animals gathered around to listen. His music soothed the Earth and made it ready to receive his seed. The magic of that sound is also said to enhance creativity and to help good dreams come true.

Archaeologists think the Kokopelli story (and symbology) emerged in Central America and made its way north as the families, clans and long-distance traders migrated. The earliest place they have found the symbol on ceramics is among Hohokam pieces more than a thousand years old. That Hohokam symbol has become the modern prototype for Kokopelli. There's another very clear Kokopelli figure on a piece of pottery found at Mesa Verde National Park and dated at about 1,000 years old. The earliest depictions of Kokopelli show him with an over-size phallus, symbolizing the fertile seeds of human reproduction. However, his image seems to have been "cleaned up" over the years, especially after the Spanish arrived. Many modern depictions show Kokopelli wearing a kilt...

The size and shape of Kokopelli's hump varies with the tribe/clan who produced the image. His arms are usually bent with elbows pointing downward. The line of his forward leg is often related to the curve of his hump. The line of his rear leg is often associated with the curve of the front line of his body. The flute is actually a nose flute, and sometimes it has a bulbous end like a clarinet. The crest on his head usually has an even number of elements. The festive crest usually represents the dual antennae of the grasshopper, another symbol Kokopelli is often associated with. If Kokopelli is depicted in the "Spirit World," those elements on his crest are feathers. In some depictions, his crest represents rays of light.

It is his whimsical nature, carefree spirit and charitable deeds that have kept him alive over the centuries. His charisma is such that he has been constantly reinvented by artists, craftsmen and storytellers for the last several thousand years. There are still lots of people around who believe in his magical powers and pray faithfully for a return visit from him.

Showing all 4 results

-

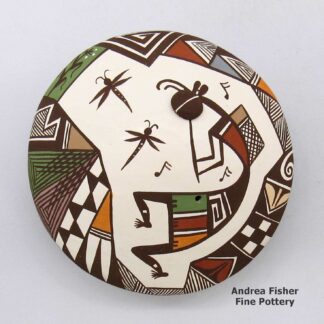

Carolyn Concho, zzac2m084m8, Polychrome seed pot with applique and geometric design

$225.00 Add to cart -

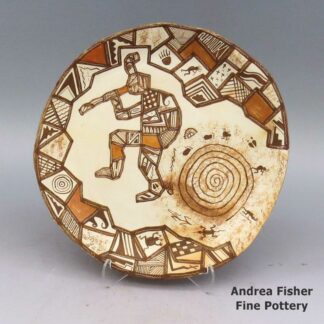

Lawrence Namoki, poho2f197: Carved, sgraffito and painted plate

$1,150.00 Add to cart -

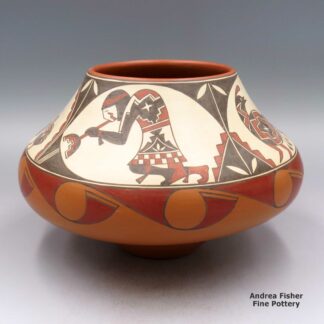

Lois Gutierrez, ahsc2e146, Polychrome jar with a 4-panel design

$2,200.00 Add to cart -

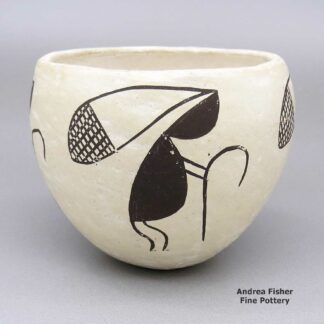

Unknown Acoma Potter, zzac2m553a, Black-on-white bowl with a Mimbres kokopelli design

$175.00 Add to cart

Showing all 4 results