Micaceous Pottery

About Micaceous Pottery

Micaceous clay pots are the only truly functional Pueblo pottery still being made. Some special micaceous pots can be used directly on the stove or in the oven for cooking. Some are also excellent for food storage. Some people say the best beans and chili they ever tasted were cooked in a micaceous bean pot. Whether you use them for cooking or storage or as additions to your collection of fine art, micaceous clay pots are a beautiful result of centuries of Pueblo pottery making.

Between Taos and Picuris Pueblos is US Hill. Somewhere on US Hill is a mica mine that has been in use for centuries. Excavations of ancient ruins and historic homesteads across the Southwest have found utensils and cooking pots that were made of this clay hundreds of years ago.

Not long ago, though, the making of micaceous pottery was a dying art. There were a couple potters at Taos and at Picuris still making utilitarian pieces but that was it. Then Lonnie Vigil felt the call, returned to Nambe Pueblo from Washington DC and learned to make the pottery he became famous for. His success brought others into the micaceous art marketplace.

Micaceous pots have a beautiful shimmer that comes from the high mica content in the clay. Mica is a composite mineral of aluminum and/or magnesium and various silicates. The Pueblos were using large sheets of translucent mica to make windows prior to the Spaniards arriving. It was the Spanish who brought a technique for making glass. There are eight mica mining areas in northern New Mexico with 54 mines spread among them. Most micaceous clay used in the making of modern Pueblo pottery comes from several different mines near Taos Pueblo.

Potters Robert Vigil and Clarence Cruz have told us there are two basic kinds of micaceous clay that most potters use. The first kind is extremely micaceous, often with mica in thick sheets. While the clay and the mica it contains can be broken down to make pottery, that same clay has to be used to form the entire final product. It can be coiled and scraped but that final product will always be thicker and heavier but perhaps smoother on the surface. This is the preferred micaceous clay for making utilitarian pottery and utensils. It is essentially waterproof and will conduct heat evenly.

The second kind is the preferred micaceous clay for most non-functional fine art pieces. It has less of a mica content with smaller embedded pieces of mica. It is more easily broken down by the potters and more easily made into a slip to cover a base made of other clay. Even as a slip, the mica serves to bond and strengthen everything it touches. The finished product can be thinner but often has a more bumpy surface than a polished piece. As a slip, it can also be used to paint over other colors of clay for added effect. However, these micaceous pots may be a bit more water resistant than other Pueblo pottery but they are not utilitarian and will not survive utilitarian use.

While all micaceous clay from the area around Taos and Picuris turns golden when fired in the open air, that same clay can be turned black by firing in an oxygen reduction atmosphere. Black fire clouds are also a common element on golden micaceous pottery but they are more a result of smoke touching the piece in random bursts of air.

Mica is a relatively common component of clay, it's just not as visible in most. Potters at Hopi, Zuni and Acoma have produced mica-flecked pottery in other colors using finely powdered mica flakes. Some potters at San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Jemez and Ohkay Owingeh use micaceous slips to add sparkle to their pieces. Hubert Candelario of San Felipe said he gets his micaceous clay somewhere along the La Bajada escarpment near Santo Domingo. The color of the clay indicates that Mark Wayne Garcia of Santo Domingo gets his micaceous clay in the same place.

Potters from the Jicarilla Apache Nation collect their micaceous clay closer to home, in the Tusas Mountains. The makeup of that clay is different and it fires to a less golden/orange color than does Taos or La Bajada clay. Some clay from the Picuris area fires less golden/orange, too. Christine McHorse, a Dineh potter who married into Taos Pueblo, used various micaceous clays on her pieces depending on what the clay asked of her in the flow of her creating. Juanita Martinez, a figure-maker from Jemez Pueblo married into and moved to Taos Pueblo. There, she began decorating her figures with bands and lines of micaceous slips.

There is nothing in the makeup of a micaceous pot that would hinder a good sgraffito artist or light carver from doing her or his thing. Some potters are also adept at adding sculpted appliqués to their pieces and slipping them with micaceous clay. There are some who have learned to successfully paint directly on a micaceous surface. The sparkly surface in concert with the beauty of a simple, well-executed shape is a real testament to the artistry of a micaceous potter.

Archaeologists and historians have long pointed at Taos and Picuris Pueblos as the birthplaces of micaceous pottery but at the 1994 Micaceous Pottery Symposium at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, Jicarilla Apache potter Felix Ortiz advanced the possibility that the people of Taos and Picuris learned how to make micaceous pottery from the Jicarilla Apache people. After all, it is Jicarilla Apache pottery made of micaceous clay from the southern Sangre de Cristo Mountains area that has been found as far away as Dismal River Culture settlements in Colorado and Nebraska and proto-Kiowa settlements in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

Showing 1–12 of 25 results

-

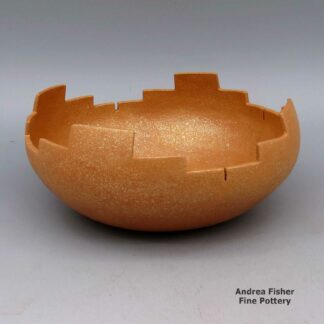

Angie Yazzie, zzta2l250: Gold micaceous prayer bowl

$1,900.00 Add to cart -

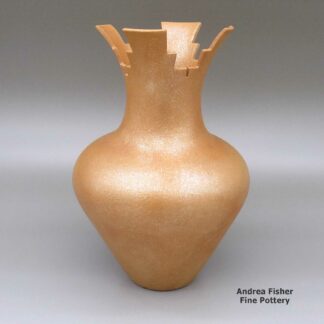

Angie Yazzie, zzta2m230m1, Micaceous gold jar with geometric cut opening

$2,500.00 Add to cart -

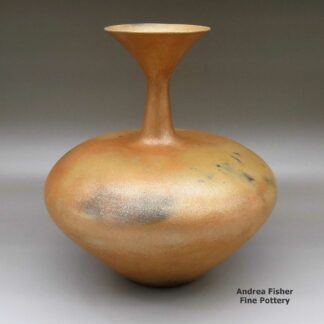

Angie Yazzie, zzta3b100, Micaceous gold jar with fire clouds

$4,900.00 Add to cart -

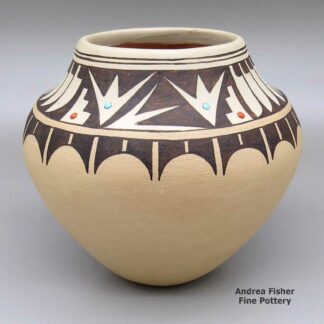

Barbara Gonzales, cjsi2c281, Micaceous jar with geometric design and inlaid turquoise and stone

$1,900.00 Add to cart -

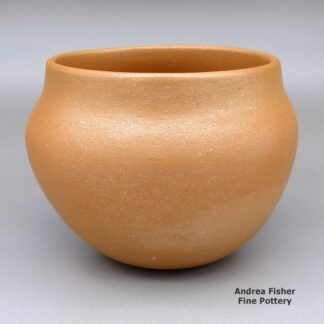

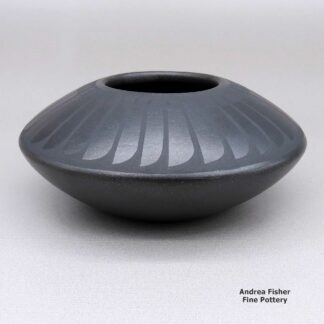

Clarence Cruz, zzsj2m150, Micaceous gold bowl

$225.00 Add to cart -

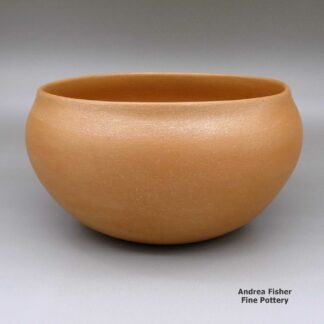

Clarence Cruz, zzsj2m152m2, Micaceous gold bowl

$395.00 Add to cart -

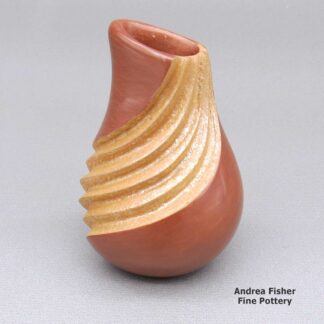

Dominique Toya, zzje3a190, Red jar with micaceous melon detail

$825.00 Add to cart -

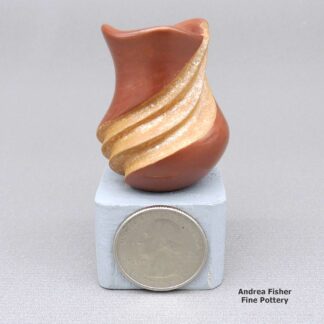

Dominique Toya, zzje3a191, Red jar with micaceous melon detail

$425.00 Add to cart -

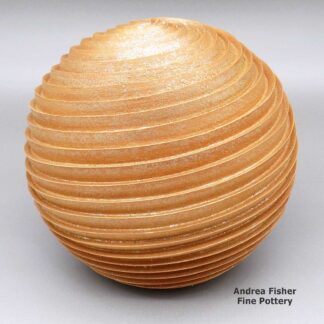

Dominique Toya, zzje3b565, Micaceous seed pot with a sharp spiral design

$3,200.00 Add to cart -

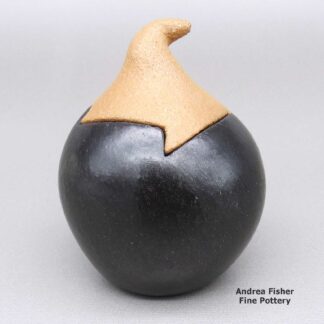

Glenn Gomez, zzta3b190, Black gourd-shaped lidded jar with golden micaceous lid

$395.00 Add to cart -

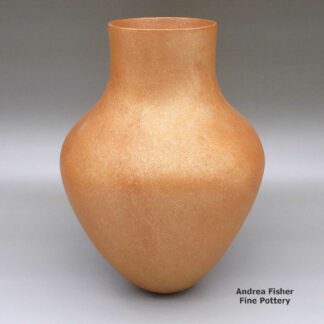

Hubert Candelario, thsf3b023, Golden micaceous jar

$1,995.00 Add to cart -

Johnny Cruz, zzsi3d140, Micaceous bowl with a geometric design

$225.00 Add to cart

Showing 1–12 of 25 results