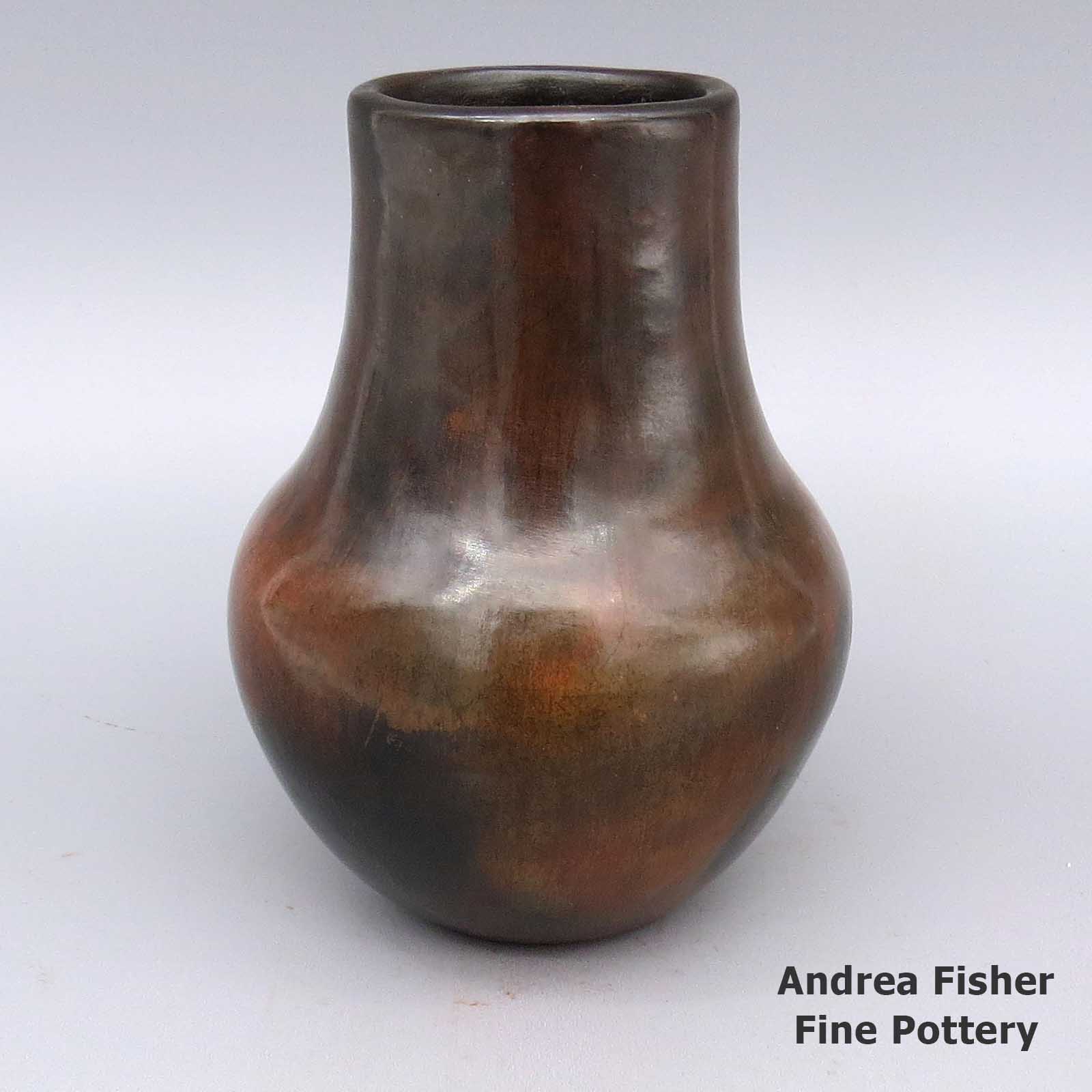

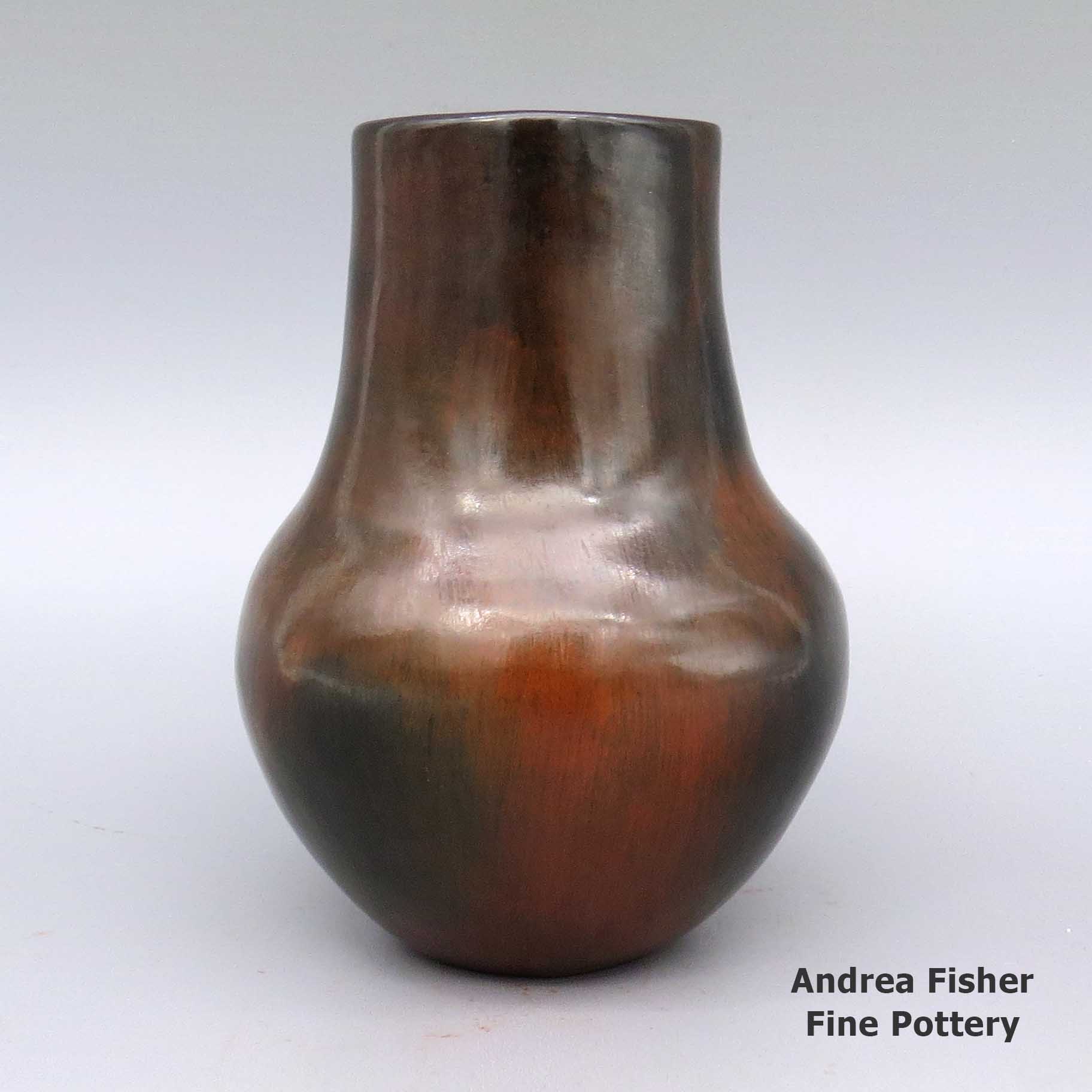

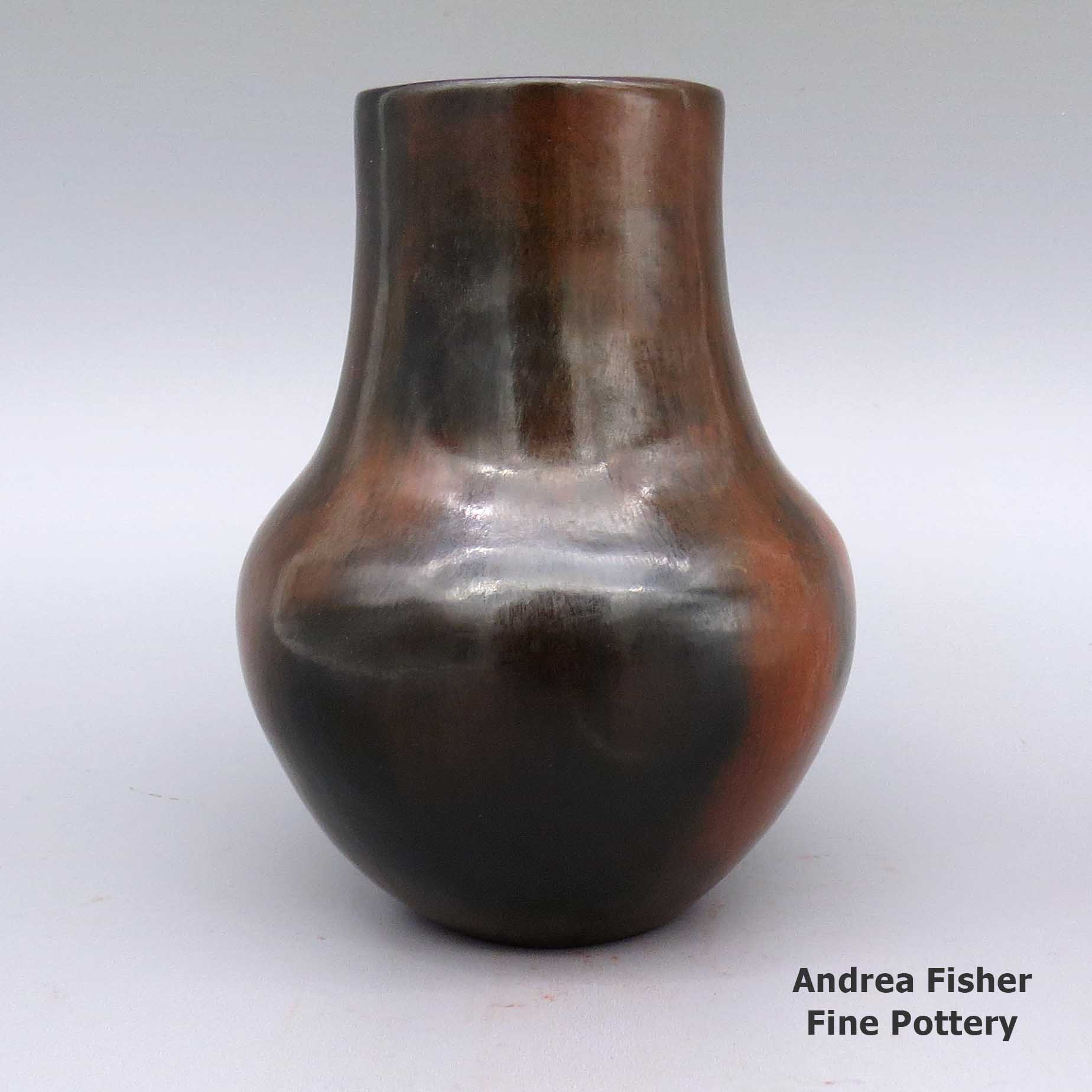

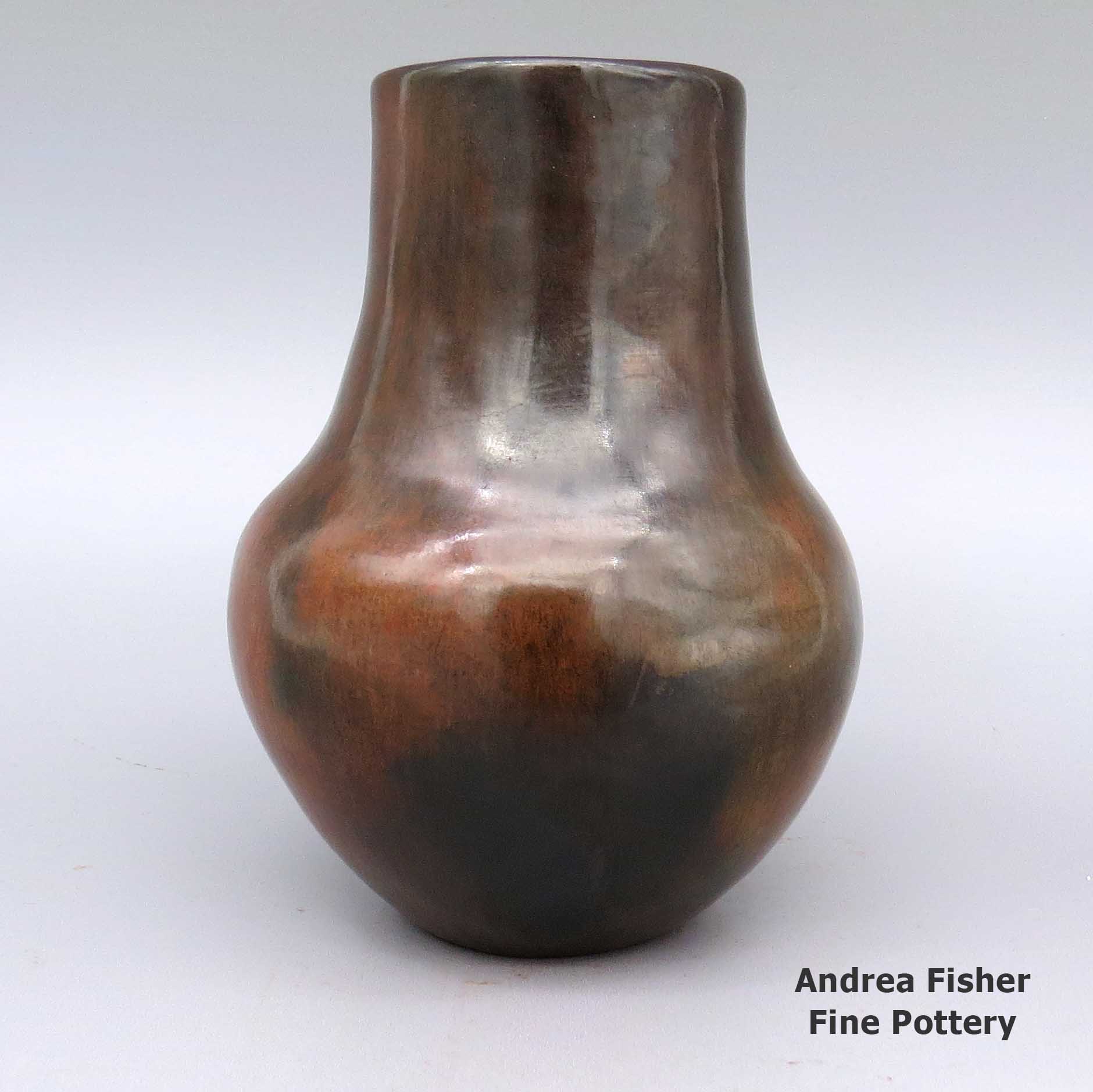

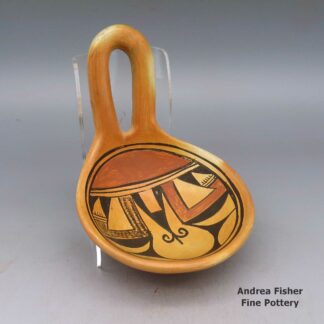

| Dimensions | 3.75 × 3.75 × 5.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2022 |

| Signature | Alice Cling |

Alice Cling, zznv2g017, Red-brown jar with fire clouds

$250.00

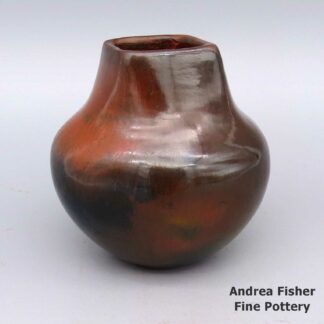

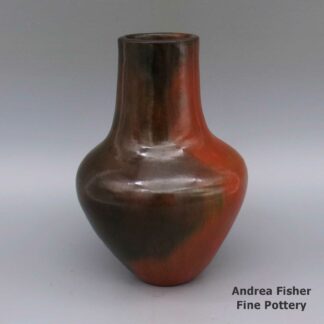

A highly burnished red-brown jar decorated only with fire clouds

In stock

- Product Info

- About the Artist

- Home Village

- Design Source

- About the Shape

- About the Design

- Family Tree

Brand

Cling, Alice

Alice started dabbling with clay as a young girl and became a recognized Dineh potter only in the late 1980s. She graduated from Intermountain Indian School (in Brigham City, UT, and no longer in existence) and returned to the Shonto area. She became a Teacher's Aide at the Shonto Boarding School in 1969, the same year she first took some of her pots to Bill Beaver at the Sacred Mountain Trading Pots near Flagstaff.

He accepted her pots but none of them sold. One day in 1976 she said she saw them still sitting on the shelf and "I said to myself, 'Alice, they are ugly.'" So she took them home again and shaped and polished them differently to make them beautiful. She's had no problem selling her work since.

Alice digs her clay from a special place near Black Mesa. She applies an iron-bearing red slip (used by the Hualapai Indians to decorate their faces) to her finished dry clay forms and polishes the surfaces with either a river stone or a Popsicle stick.

When firing, the ash that falls onto the pots from the juniper wood-fueled pit fire combines with the clay to produce the red-orange-purple-brown-black blushes (also known as fire clouds) on her pottery. After firing, she usually applies a light coating of warm piñon pine pitch and burnishes each pot to a distinctive low sheen.

Alice's personal contribution to the renaissance of Navajo pottery is the magnificent coloration she achieves on her softly burnished forms. Except for fire clouds and the occasional raised rope or biyo' around the shoulder or the opening, her pots are undecorated.

One of Alice's pieces was exhibited in the Vice-Presidential Mansion in Washington, DC, in 1978 and her career took off from there. Her elegant, gracefully austere pots are included with the avant-garde potters in Pottery by American Indian Women, the Legacy of Generations exhibition and book by Susan Peterson, 1997, at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C.

Some Exhibits that featured Alice's work

- Our Stories: American Indian Art and Culture in Arizona. Heard Museum West. Surprise, AZ. June 2006 - October 2009

- The Navajo Folk Art Festival. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. February 2002

- Fabric, Wood and Clay: Diverse World of Navajo Art. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, AZ. January 2002 - July 2002

- Indian Market: New Directions in Southwestern Native American Pottery. Peabody Essex Museum. Salem, MA. November 2001 - March 2002

- The Art of the People. Gallup Cultural Center. Gallup, NM. August 2001

- The Legacy of Generations: Pottery by American Indian Women. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. February 14, 1998 - May 17, 1998

- The Legacy of Generations: Pottery by American Indian Women. The Museum of Women in the Arts. Washington, DC. October 9, 1997 - January 11,1998

- Contemporary Art of the Navajo Nation. Cedar Rapids Museum of Art. Cedar Rapids, IA. 1994

- The Navajo Show and Sale. Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona. Tempe, AZ. December 1988

- Anii Ánáádaalyaa̕ ígíí (Recent Ones That Are Made): Continuity & Innovation in Recent Navajo Art. Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian. Santa Fe, New Mexico. July 10, 1988 - October 30, 1988

- In the Spirit of Tradition: The Heard Museum Craft Arts Invitational. Heard Museum. Phoenix, AZ. March 1986 - May 1986

- Alice Cling. Navajo Tribal Museum. Window Rock, Arizona. May 13-30, 1985

Some Awards Alice earned

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery: Best of Division

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style all forms: First Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style alternate forms: First Place

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style alternate forms: Third Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style, jars (with or without handles or lids): Second Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style, jars (with or without handles or lids): Third Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 802 - Navajo style, other forms: Third Place

- 1994 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped and unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: Second Place

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Unslipped pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: First Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped and unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: First Place

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any forms: Best of Division

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any forms, Category 1611 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style: Second Place

- 1989 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, Category 701 - Navajo pottery: First Place

- 1989 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional, Category 701 - Navajo pottery: Second Place

- 1988 Navajo Nation Fair Arts and Crafts Competition, Classification III - Pottery, patch-coated, Navajo: Best in Class and First Place

- 1988 Navajo Nation Fair Arts and Crafts Competition, Classification III - Pottery, patch-coated, Navajo: First Place

- 1987 Gallup InterTribal Ceremonial, Classification IV - Pottery, undecorated, any object: First Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unslipped and unpainted: First Place

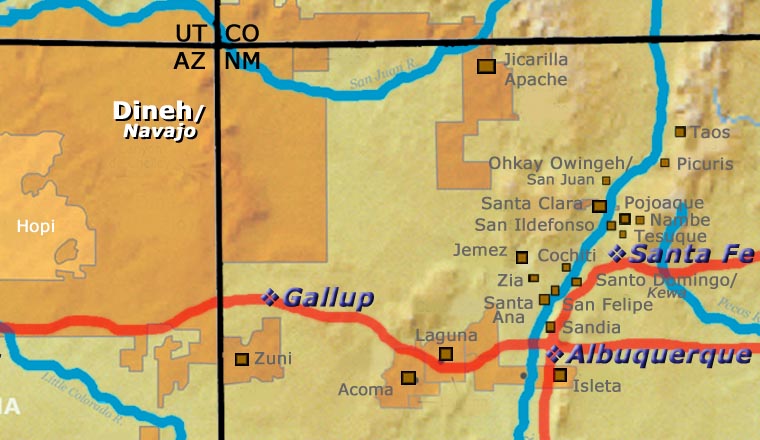

About the Dineh

Historical and archaeological evidence points to the Dineh entering the Southwest around 1400 AD. Their oral history still contains stories of that migration as the journey began in eastern Alaska and northwestern Canada centuries after their ancestors made the journey across the Bering Land Bridge from central Asia about 10,000 years ago. They were primarily hunter-gatherers until they came into contact with the Pueblo peoples and learned the basics of survival in this drier climate. Dineh oral history points to a long relationship between the Dineh and the Ancestral Puebloans as they learned from and traded with each other.

When the Spanish first arrived, the Dineh occupied much of the area between the San Francisco Peaks (in Arizona), Hesperus Mountain and Blanca Peak (in Colorado) and Mount Taylor (in New Mexico). Spanish records indicate they traded bison meat, hides and stone to the Puebloans in exchange for maize and woven cotton goods. It was the Spanish who brought sheep to the New World and the Dineh took to sheep-herding quickly with sheep becoming a form of currency and sign of wealth.

When the Americans arrived in 1846, things began to change. The first fifteen years were marked by broken treaties and increasing raids and animosities on both sides. Finally, Brigadier General James H. Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to round up the Dineh and transport them to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico for internment. Carson succeeded only by engaging in a scorched earth campaign in which his troops swept through Dineh country killing anyone carrying a weapon and destroying any crops, livestock and dwellings they found. Facing starvation and death, the last band of Dineh surrendered at Canyon de Chelly.

Carson's campaign then led straight into "the Long Walk" to Bosque Redondo, a 300-mile trek during which at least 10% of the people died along the way. At Bosque Redondo they discovered the government had not allocated an adequate supply of water, livestock, provisions or firewood to support the 4,000-5,000 Dineh interned there. The Army also did little to protect the Dineh from raids by other tribes or by Anglo citizens. The failure was such that the Federal government and the Dineh negotiated a treaty that allowed the people to return to a reservation that was only a shadow of their former territory little more than a couple years after they had left. However, succeeding years have seen additions to the reservation until today it is the largest Native American Reservation in the 48 contiguous states.

Large deposits of uranium were discovered on the Dineh Nation after World War II but the mining that followed ignored basic environmental protection for the workers, waterways and land. The Dineh have made claims of high rates of cancer and lung disease from the environmental contamination but the Federal government has yet to offer comprehensive compensation.

The location of the Dineh Nation

For more info:

Navajo Nation at Wikipedia

Diné people at Wikipedia

Navajo Nation Government official website

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Dineh Pottery

As a nomadic people, pottery didn't make much sense to the Dineh as they made the journey south from the northwestern corner of North America. When they came up against the Ancestral Puebloans they settled into a more sedentary lifestyle. The puebloans taught them much about how to survive in this climate on this landscape. That included the making of pottery for utilitarian purposes. That suited the Dineh religious authorities and as more and more Anglo settlers came into the area, they developed a business selling utilitarian wares to them. That essentially ended when the United States came into ownership of the land and American traders arrived with their relatively inexpensive and long-lasting enameled and cast iron cookware. Then pottery production scaled back to just ceremonial pieces being made.

Rose Williams learned how to make pottery from her aunt, Grace Barlow. Rose learned how to make basic brown pottery in utilitarian shapes. She only allowed herself the occasional rope biyo' for decoration, relying more on how she stacked her wood in the firing to make the fire clouds she wanted. Rose liked to make large brown jars which were often used to make drums. Living to be 99 years old and making pottery almost until she passed, Rose taught many people how to make pottery.

Grace Barlow also taught her granddaughter, Betty Manygoats. Betty in turn, taught all her children how to make pottery. Only Elizabeth has made a living at it.

Other modern potters on the reservation have usually learned how to make pottery the traditional way in the classrooms at the Institute for American Indian Arts.

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Fire Clouds

Fire clouds are a product of the firing process. They are generally random darkenings of a piece where it was touched by a wayward plume of smoke and the clay absorbed some of the carbon in it. Conversely, in an oxygen-reduction atmosphere (which is how Tewa potters turn their otherwise red pieces black), surfaces randomly exposed to open air don't turn as black while surfaces protected from exposure to the oxygen-reduction atmosphere turn red. In some pueblos, the appearance of fire clouds is a testament to the lack of experience of the potter. In others it's a testament to the greater experience of the potter.

Dineh potters often stack their firewood in ways to generate fire clouds on their brown clay as that may be the only decoration on the piece.

Fire clouds on Hopi pottery are usually seen as a darker blush on an otherwise yellow piece. That is a result of their yellower clay and their use of cedar bark and sheep manure for firing. Franklin Tenorio of Santo Domingo also often used cedar bark to fire his pieces but he liked to make his surfaces look smudged and smoky by partially blocking the air flows around his fires. In contrast, his cousin Thomas Tenorio prefers to fire his pieces inside a metal container that denies any entrance to fire-cloud generating smoke or atmosphere.

Potters who work with micaceous pottery also work with fire clouds. When firing in a free-oxygen atmosphere, fire clouds may be the only decoration on a piece. When firing in an oxygen-reduction atmosphere to produce a black piece, "fire clouds" are any lighter areas left on the surface after the firing is complete.

Grace Barlow Family and Teaching Tree - Dineh

Disclaimer: This "family and teaching tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this group and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

The only connections we've found between Grace Barlow and other Dineh potters are through her niece, Rose Williams, and her granddaughter, Betty Manygoats. It seems they all lived in a remote area near Coal Mine Mesa and they made pottery like in the old days: all the potters gathered together, worked together, and learned from each other. They made ceremonial and utilitarian pottery like in the old days: pottery-as-art is a new thing to the Dineh. Then many of the people were uprooted from the Coal Mine Mesa area and forced to move to Tuba City while the Hopi and Dineh lawyers fought it out in federal court. That took a couple decades but eventually the Dineh prevailed and they were allowed to return and live on their land again.

- Rose Williams (1915-2015), learned from her aunt, Grace Barlow

- Alice Cling (1946-)

- Susie Crank & Lorenzo Spencer

- Sue Ann Williams (1956- )

- Lorraine Williams-Yazzie (1955-)(former daughter-in-law)

- Stuart Roy (son-in-law)

- Raven Roy

- Stuart Roy (son-in-law)

- Silas Claw (1913-2002) & Bertha Claw (1926-)

- Faye Tso (1933-2004)

- Lorena Bartlett

- Louise Rose Goodman (student of Lorena) (1937-2015)

- Betty (Barlow) Manygoats (learned to make pottery from her paternal grandmother, Grace Barlow and from her cousin, Lorena Bartlett)

- Elizabeth Manygoats

- Evelyn Manygoats

- Evelyn Manygoats & Jonathan Chee

- Louise Manygoats

- Rita Manygoats