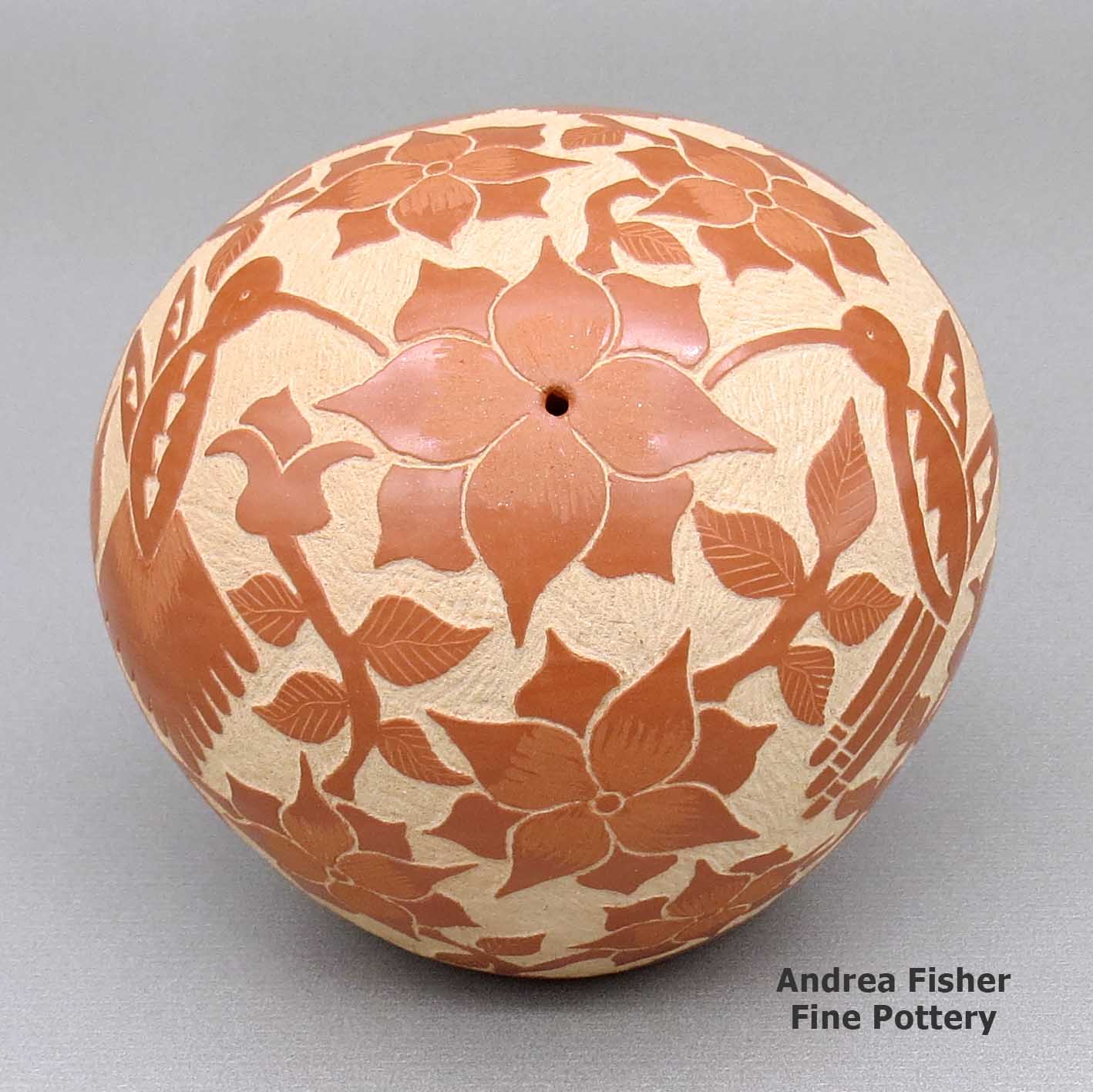

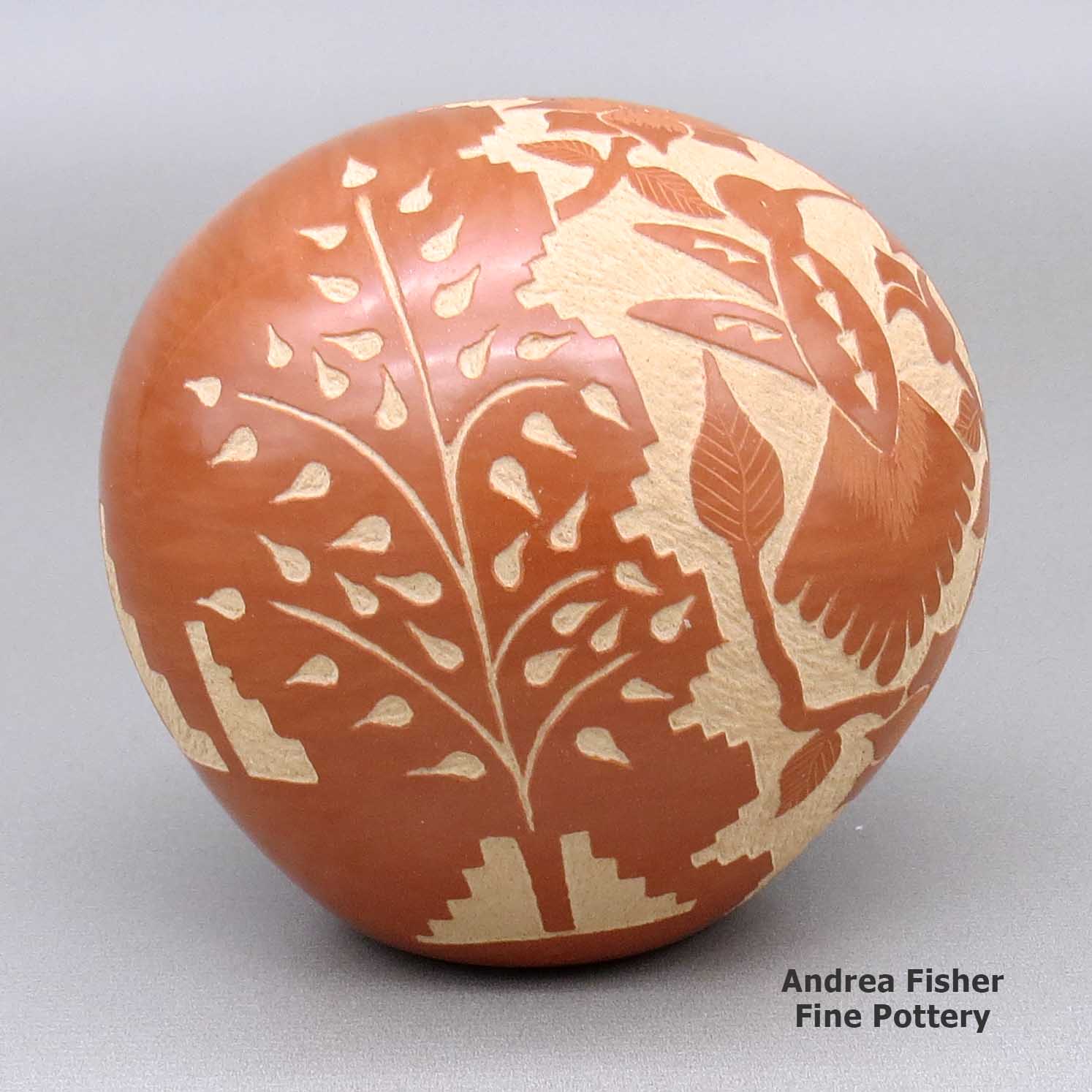

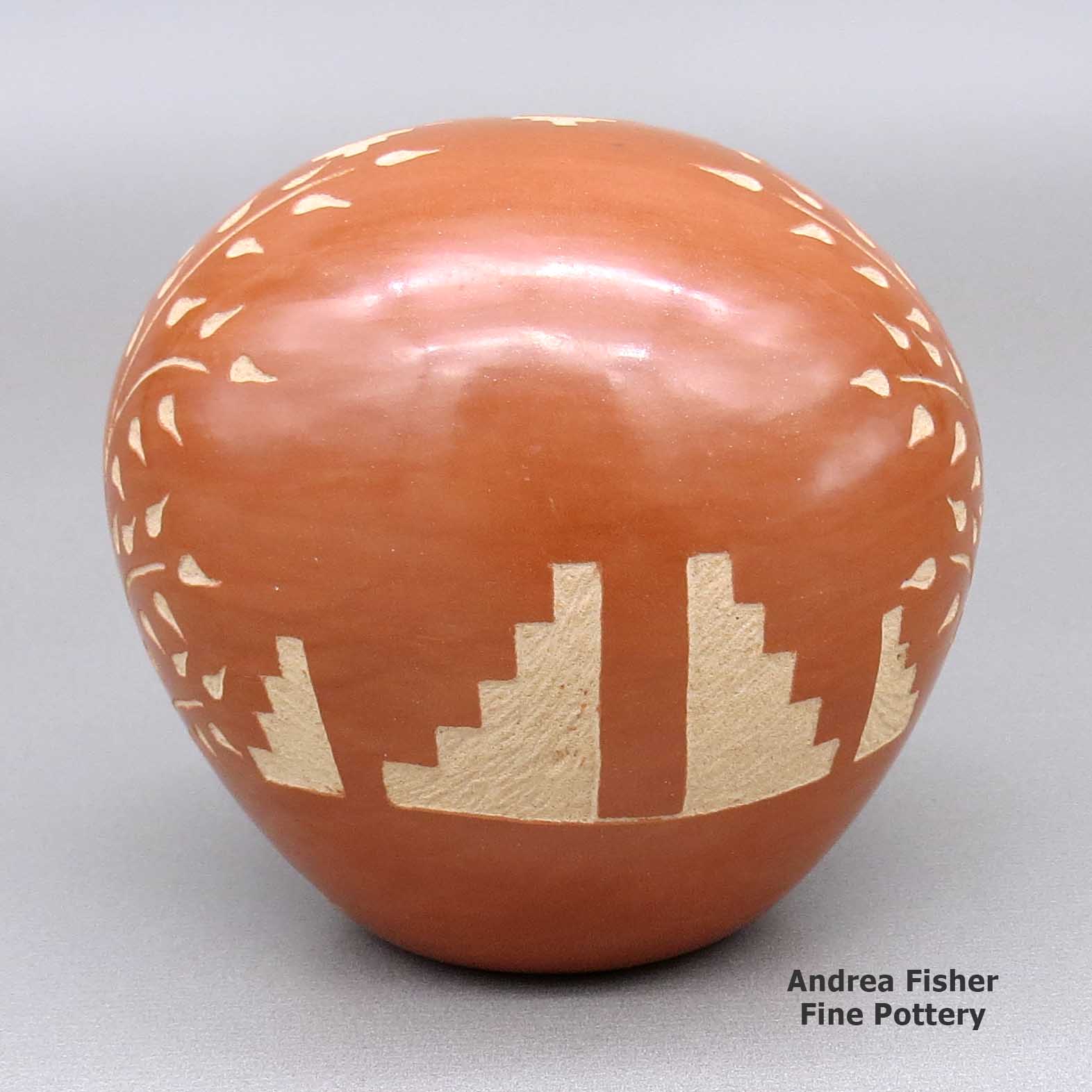

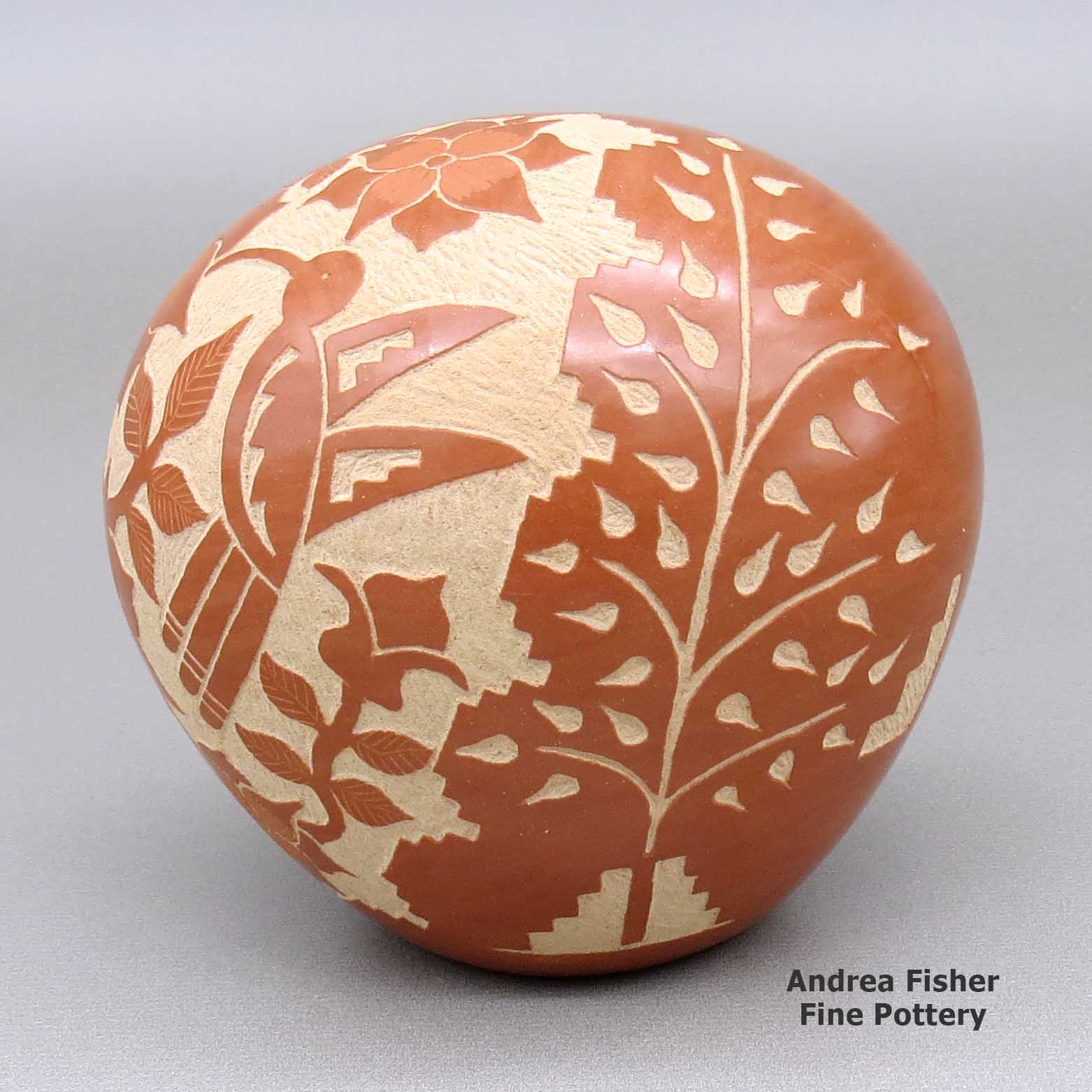

| Dimensions | 3.5 × 3.5 × 3.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | Alvina Yepa Jemez Pueblo, NM |

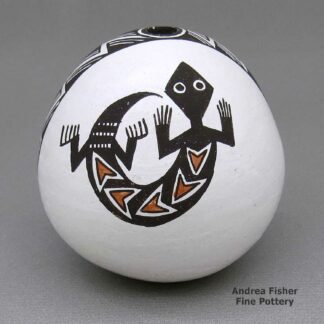

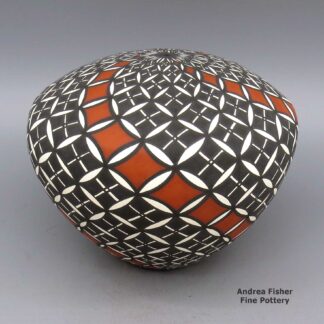

Alvina Yepa, zzje3c310, Seed pot with sgraffito design

$325.00

A red seed pot decorated with a sgraffito hummingbird, flower, plant, kiva step and geometric design

In stock

- Product Info

- About the Artist

- Home Village

- Design Source

- About the Shape

- About the Design

- Family Tree

Brand

Yepa, Alvina

Alvina Yepa ia a potter from Jemez Pueblo. She was born into the Sun Clan in August 1954. Her paternal grandparents were Cristino and Juanita Fragua Yepa, her maternal grandparents Frank and Louisa Fragua Toledo. Her parents were Nick and Felipita Yepa.

Alvina grew up making pottery, watching and working with her mother. She started painting and polishing pottery for her mother when she was eight years old. The only time in her life since when she wasn't making pottery (as much) was when she lived in Richfield, UT, working as a bank teller. She said she enjoyed working at the bank and was thankful for the experience but after six years, she got homesick for family and culture.

Alvina entered her first piece at the Santa Fe Indian Market in 1986. In 1987 she earned a First Place ribbon and a Best of Division ribbon. That was the beginning of a long string of ribbons earned at Santa Fe. Alvina has also participated in the Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market, the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show, the Prescott Indian Art Market, the University of San Diego American Indian Celebration, the Atlanta Spirit of America Show and others. In 2008 she had a special exhibit As Mother Earth Spins, She Speaks: Pueblo Pottery by Alvina Yepa at the Booth Western Art Museum.

In 1997 Alvina was invited to participate in the 14th Annual Phoenix Indian Center Bolo Tie Dinner and Awards Banquet as a "Collector's Choice Artist." Some of her work is also in the object collection of the Heard Museum.

Alvina is known for making intricately etched, larger-scale jars that often incorporate a melon-style swirl. She works mostly with Jemez red clay and carves contemporary designs into it.

Some of the Awards Alvina has earned

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-E, Contemporary using traditional materials and techniques, Best of Division

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II-E, Category 906 - Sgraffito and carved, any form, First and Second Place

- 2022 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Class. Awarded for artwork: "Hummingbird Water Jar"

- 2022 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Carved, incised, sgraffito, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Hummingbird Water Jar"

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffitto, Any Form: Second Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D, Contemporary Pottery, Any Form or Design, Using Native Materials with or without Added Decorative Elements, Traditional Firing Techniques, Category 801 - Sgraffitto, Any Form: Honorable Mention

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional Burnished Black or Red Ware, Incised, Painted or Carved, Category 702 - Carved or incised, black or red, over 8": Second Place

- 2003 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification VIII - Pottery, Division A - Traditional/Native clay/hand-built (painted): Honorable Mention

- 1996 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification VII - Pottery, Division A - Traditional construction and firing methods: Best of Division. Awarded for artwork: Red Melon Bowl

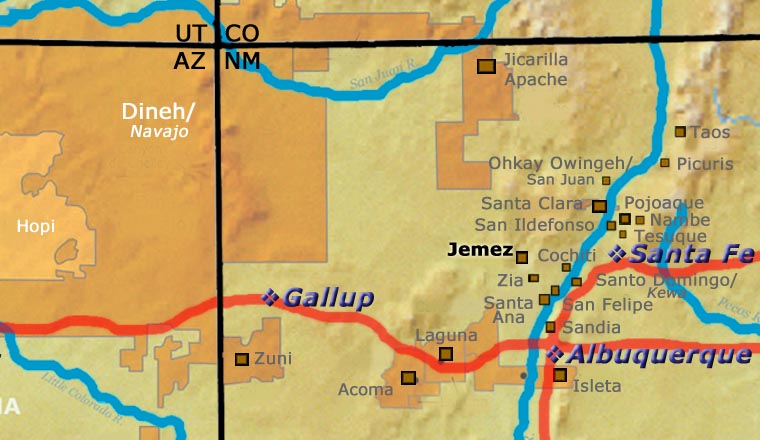

A Short History of Jemez Pueblo

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward, across the Upper San Juan River into the Gallina Highlands, then over the hill to the Canyon de San Diego area in the southern Jemez mountains. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa. The large migrations out of the Four Corners area began around 1250 and the area was almost entirely depopulated by 1300. The Towa-speakers who went southeast were pretty much settled by about 1350.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that pot sherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed by other Hopis around 1625). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, agriculture was hard. The Jemez had always been travelers and traders. Their people had traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico for generations. In those days they also made a lot of pottery and trading pottery with Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos for food was a brisk business.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and helped evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains.

It was around that time that the Hopi themselves destroyed Awatovi, the largest pueblo in the Hopi area (many of the people of Awatovi also spoke Towa). A Spanish missionary with a few soldiers had appeared at Awatovi in 1696 and forced the rebuilding of the mission. He also started getting people into the church. The leader of Awatovi went to the other Hopi pueblos and told their leaders that his people had strayed too far: they must be destroyed to cleanse the Earth of their sins. In the winter of 1700-1701, men from Walpi, Oraibi and a couple other pueblos invaded Awatovi while the men were in their kivas. The invaders pulled the ladders out of the kivas, poured baskets of hot red chile peppers and burning pine pitch down, then killed almost everyone. When the frenzy was over they burned the pueblo down and salted the earth around it so it would never be reoccupied.

On their return to the Jemez Mountains around 1700, the Jemez people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities. Even today, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Dineh territory at Jeddito.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Pecos Pueblo (more properly known as Cicuyé) are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé were the easternmost speakers of the Towa language in the Southwest. After the Pueblo Revolt, the Pecos area fell on increasingly hard times (constant Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, increasing drought). The pueblo was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents relocated to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Pecos tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Pecos families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Jemez Pueblo Pottery

Some of the Towa-speaking people had been making a type of plainware pottery (simple, undecorated, utilitarian) when they were still in the Four Corners area, while others had developed a distinctive style of black geometric designs on white pottery. In migrating to the Jemez Mountains, they brought their knowledge and techniques with them but had to adapt to the different materials available to work with. Over time, the Jemez got better in their agricultural practices and began trading agricultural goods to the people of Zia Pueblo in return for pottery. The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for them and by the mid-1700s, the Jemez were producing almost no pottery of their own. After the Americans took over, whatever pottery was discovered in official excavations of abandoned Jemez pueblos was removed to the basement of a museum somewhere else. The Jemez were relieved of virtually all their patrimony this way.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Cicuyé (Pecos) Pueblo are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé, with a couple smaller outlying pueblos in the Galisteo Basin, were the only other speakers of the Towa language in New Mexico. When that area fell on increasingly hard times (Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, drought), Cicuyé was abandoned. That happened in 1838 when the last 17 residents moved to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Cicuyé families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

When general American interest in Puebloan pottery started to take off in the 1960s, the people of Jemez sought to recover that lost heritage. Today, the practice of traditional pottery-making is very much alive and well among the Jemez.

The focus of Jemez pottery today has turned to the making of storytellers, an art form that now accounts for more than half of their pottery production. Storytellers are usually grandparent figures with the figures of children attached to their bodies. The grandparents are pictured orally passing tribal songs and histories to their descendants. While this visual representation was first created at Cochiti Pueblo (a site in close geographical proximity to Jemez Pueblo) in the early 1960s by Helen Cordero, it speaks to the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren of every culture.

The pottery vessels made at Jemez Pueblo today are no longer black-on-white. Instead, the potters have adopted many colors, styles and techniques from other pueblos to the point where Jemez potters no longer have one distinct style of their own beyond that which stems naturally from the materials they themselves acquire from their surroundings: it doesn’t matter what the shape or design is, the clay says uniquely "Jemez".

About the Seed Pot

It was a matter of survival to the ancient Native American people that seeds be stored properly until the next planting season. Small, hollow pots were made to ensure that the precious seeds would be kept safe from moisture, light, bugs, reptiles and rodents.

After seeds were put into the pot, the small hole in the pot was plugged. The following spring the plug was removed and the seeds were shaken from the pot directly onto the planting area.

Today, seed pots are no longer necessary due to readily available seeds from commercial suppliers. However, seed pots continue to be made as beautiful, decorative works of art.

The sizes and shapes of seed pots have evolved and vary greatly, depending on the vision of Clay Mother as developed through the artist. The decorations vary, too, from undecorated white, buff or red seed pots to multi-colored painted, carved, applique and sgraffito designs, sometimes with inlaid gemstones, micaceous clay and silver or clay lids.

Because of the multitude of shapes and sizes, the name "seed pot" is generally reserved for pieces with tiny openings.

About Wildlife and Nature Designs

What we're calling "wildlife and nature designs" are usually quite contemporary designs carved, painted and/or etched by hand on a hand-made piece of pottery. In the same genre are bird, butterfly, dragonfly, moth, bat and fish designs. Some have seaweed and vines, some have trunks and branches, some have leaves and/or flowers and/or berries, some don't. Some are composed of optical illusions while others are very clear to the eye. While the designs and layouts tend to be quite contemporary, sometimes they incorporate elements of ancient settings.

Felipita Yepa Family Tree - Jemez Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Felipita Toledo Yepa (b. 1922) and Nicolas Yepa (b. 1915)

- Alvina Yepa (1954-)

- Jose and Ida (Toya) Yepa

- Emma Yepa (1968-) and Albert Arizmendt Sr

- Albert Arizmendt Jr.

- Breanna Arizmendt

- Diana Yepa

- Emma Yepa (1968-) and Albert Arizmendt Sr

- Cristino Yepa

- Lawrence (1948-) and Lupita (Toya)(c. 1953-) Yepa

- Elston Yepa and Dina Yepa (Santo Domingo)

- Wallace Yepa

- Priscilla Yepa

- Salvador Yepa (1940-) and Doreen Carpenter

- Marcella Yepa (1964-)

- Benjamin Yepa

- Donovan Yepa

- Shaunna Yepa

- Marcella Yepa (1964-)

- Salvador Yepa (1940-) and Florence Yepa (Loretto)(1949-)

- Miriam Brenda (Panana) Loretto (1967-)

- Robin Loretto

- Matthew Panana

- Ryan Panana

- Victor Loretto

- Adrianna Loretto (1978-)

- Emmet Trevor Yepa

- Miriam Brenda (Panana) Loretto (1967-)