| Dimensions | 9.25 × 9.25 × 8.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | Avelia Anderson .J. Peynetsa Zuni, with copyright symbol |

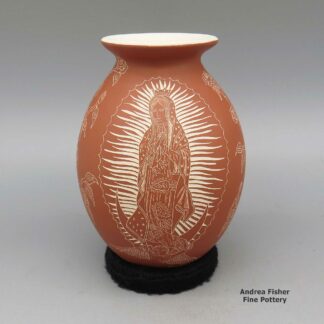

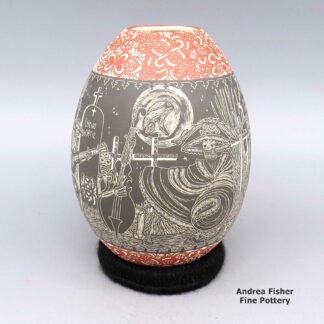

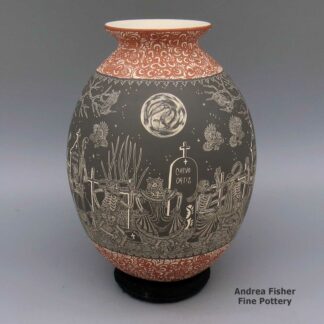

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa, zzzu3c031, Polychrome jar with a geometric design

$1,450.00

A polychrome jar decorated with a traditional Zuni rain bird, fine line, and geometric design

In stock

- Product Info

- About the Artist

- Home Village

- Design Source

- About the Shape

- About the Design

- Teaching Tree

Brand

Peynetsa, Anderson Jamie

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa is the son of Anderson and Avelia Peynetsa, nephew of aunts Agnes Peynetsa and Priscilla Peynetsa. He was born at Zuni Pueblo in 1997.

Anderson Jamie Peynetsa is the son of Anderson and Avelia Peynetsa, nephew of aunts Agnes Peynetsa and Priscilla Peynetsa. He was born at Zuni Pueblo in 1997.Jamie's been making pottery since he was 11 years old, learning from his brother, his father and at Zuni High School. He participated in his first show in 2008, the Santa Fe Indian Market, and earned a First Place ribbon in the Junior Pottery Division. In 2018 he earned a First Place ribbon at the Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair & Market for a large traditional Zuni jar with a traditional geometric design.

Jamie's favorite shapes are either contemporary (he sometimes makes duck pots) or traditional Hawikuh-Revival styles. His favorite designs are a mix of modern fine line and traditional Zuni designs.

He says he gets his inspiration from his father and his goal is to learn all he can from his dad and produce pots at least as good as his. For the last several years Jamie has been working more with his mother, Avelia. She makes some of the pots that he paints.

Avelia is the great-granddaughter of Catalia Zunie, the woman who recruited Daisy Hooee to teach traditional pottery-making classes at Zuni High School in the 1960s.

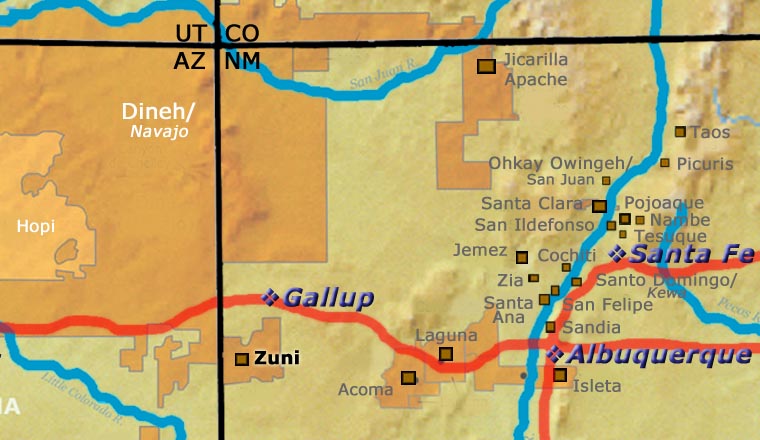

A Short History of Zuni Pueblo

"K'ynánas'tipe stretched his legs to the four great seas, then gradually he settled down and called out, 'where my heart and navel rest, beneath them mark the spot and build your town there for that shall be the midmost place of Mother Earth.' As he squatted over the middle of the plain and the valley Zuni, he drew in his legs and his feet marked the trails leading outward like the radiating web of a spider. The fathers of the people built on this spot and rested their fetishes there." - Frank H. Cushing, Outlines of Zuni Creation Myths, pp. 428-9

Archaeologists have dated some sites on the Zuni Reservation back to the Paleo-Indian Period, more than 4,500 years ago. During the Archaic Period (2,500 BCE to 0 CE), the forebears of the Zuni were hunter-gatherers and just beginning to develop agriculture. The Basketmaker Period (0 CE to 700 CE) saw agriculture become more developed and the Zunis make their first pottery. The Pueblo I Period (700 CE to 1100 CE) saw an expansion of the population and larger settlements were built in the Zuni River area along with the development of the first painted Zuni pottery.

The Pueblo III Period (from 1100 to 1300 CE) saw further population growth in the Zuni River area and a shift from small houses to larger, plaza-oriented villages. The Pueblo IV Period (1300 to 1500 CE) was the time of significant bad weather, great drought and the beginning of the flood of Athabascans and Utes. Many tribal groups were forced out of the Four Corners area and relocated to locations near the Rio Grande, Rio Puerco, Zuni River and Little Colorado River. The main Zuni Pueblo was founded during this time but there were several other large villages in the area, too.

In 1540 Francisco Vasquez de Coronado arrived at the gates of Hawikuh, at the time one of the larger of seven Zuni pueblos. He first approached the pueblo at the end of a four-day religious festival. The Zuni chief had spilled a line of corn meal across the ground before the entrance to the pueblo, meant to signify to the Spanish that they shouldn't cross the line and enter the village yet. Coronado interpreted that line of corn meal as an act of war and immediately ordered his soldiers to attack.

Coronado was almost killed in the fighting (Zuni warriors had dropped a large rock on him, knocking him off his ladder and almost crushing him) but his soldiers did finally win the battle. As Coronado and his men brought horses and sheep with them, they were probably the first such livestock the Zunis had ever seen. The gold the Spaniards were looking for: it turned out to be Sikyátki Polychrome bowls and jars, yellow clay gifts from the Hopi people to the Zuni people.

The Zuni chief did give Coronado a refugee from the Plains tribes, someone who'd somehow made his way as a lone traveler to Hawikuh. That refugee was supposed to be a guide for Coronado and his men but he was instructed by the Zuni chief to take Coronado into the Plains and get him lost there. When Coronado finally realized that, more than a year later, he ordered the guide executed, then turned his men around and headed back to Zuni and Mexico.

When he passed by Zuni in 1542, Coronado left three Mexican Indians behind with the tribe. They most likely informed the tribal leaders of the extent of the Spanish domain in Mexico and the power they exercised there.

Except for a couple passing exploratory expeditions, the Zuni pueblos were left alone until the 1620s. Then came the friars who oversaw the construction of a mission church at Hawikuh in 1629. At first the Zuni people were friendly with the priests but with the forced labor requirements and forced religious conversions, the priests wore that welcome out quickly. Relations had changed drastically for the worse by the time of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. Zuni warriors killed the priests and burned the missions but they preserved the relics and icons the priests had brought from Spain.

The tribe built a village near their fortress atop Dowa Yalanne and prepared to defend their people and way of life against the Spanish army. When Don Diego de Vargas arrived with troops in 1692, he attacked the fortress twice and failed. Then he negotiated with the Zuni war chief and was allowed to ascend to the top of Dowa Yalanne. He was given a tour of the property and he found many relics from the destroyed missions there. With that knowledge, he arranged a peace between the Spanish and the tribe. Between 1693 and 1700 the tribe consolidated all their small villages into what is now the Pueblo of Zuni.

Photo courtesy of Ken Lund, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License 2.0 Generic

Traditional Zuni Designs

Anthropologists say the Zuni people have been isolated for so long, there are no referrents to where their language came from. The images they paint on pottery, though, show some signs of cross-pollination with the Hopi, Acoma, Laguna and some of the Rio Grande pueblos.

Among those images are the heart-line, as in deer-with-heart-line. At some pueblos, that has become bear-with-heart-line and antelope-with-heart-line. Sometime around 1890, a Laguna potter made the journey to Zuni to learn from a potter there how to make better pottery. He stayed only a few months before returning to Laguna, via Acoma. He brought back better knowledge of mixing the clay, making the paints and painting the designs. Among those designs was the deer-with-heart-line.

At the time of first Spanish contact, there were seven Zuni pueblos spread out along the Zuni River. By about 1720, that was reduced to one. When the American archaeologists arrived, they set about excavating almost every abandoned village they could find. In the process, many pieces of ancient pottery came to light. That's where the names Matsaki Polychrome and Red-on-buff (matte paint on white and red slips, produced from about 1375 CE to about 1700 CE), Kwakina Polychrome (glaze paint on a white slip, produced from about 1325 to about 1400) and Heshotauthla Black-on-red and Polychrome (glaze decorations, produced from about 1275 to about 1400) came from. A primary difference between Kwakina and Heshotauthla designations is the color the inside of the bowl is slipped with. The decorations on both are painted with lead glaze colors and are taken from the same design library, which includes many designs common to the Mogollon Highlands in eastern Arizona (such as St. Johns Polychrome), although the designs tend to be not as well executed.

The advent of Matsaki Polychrome and Red-on-buff coincides with the entrance of an immigrant community from the north: the land of the Hopi. With them came the basic design library of what we now refer to as "Sikyatki Polychrome." Production of Kwakina- and Heshotauthla-style pottery dropped off quickly after the arrival of those who produced the Matsaki styles. It was around that time, too, that the Zuni villages around the Zuni Mountains were abandoned and the people pulled back to the pueblos along the lower Zuni River.

After Spanish contact and conquest, the Zunis were reduced to about one-tenth their population by Spanish diseases and labor practices. Before too long, they were gathered together in one village near the bank of the Zuni River. Their image catalog changed, too. When the American archaeologists and ethnologists came, they removed virtually every artifact of Zuni history they could dig up or find otherwise. Then they spirited it all away to storerooms on either coast, where most of it remains in boxes in dingy basement rooms today.

In 1986, Josephine Nahohai and several members of her family traveled to Washington DC and explored the basement storage shelves of the Smithsonian Institute, copying every ancient Zuni shape and design they found into their notebooks. When they returned to Zuni, their drawings became the basis for many of what are now referred to as traditional Zuni designs. Among those designs are symbols for mountains and forest, and images of frogs, tadpoles, dragonflies, serpents and rainbirds. Other Zuni potters have since visited other storerooms of ancient Zuni pottery and brought drawings of those shapes and designs back to the pueblo, too.

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

Traditional Zuni Designs

Anthropologists say the Zuni people have been isolated for so long, there are no referrents to where their language came from. The images they paint on pottery, though, show some signs of cross-pollination with the Hopi, Acoma, Laguna and some of the Rio Grande pueblos.

Among those images are the heart-line, as in deer-with-heart-line. At some pueblos, that has become bear-with-heart-line and antelope-with-heart-line. Sometime around 1890, a Laguna potter made the journey to Zuni to learn from a potter there how to make better pottery. He stayed only a few months before returning to Laguna, via Acoma. He brought back better knowledge of mixing the clay, making the paints and painting the designs. Among those designs was the deer-with-heart-line.

At the time of first Spanish contact, there were seven Zuni pueblos spread out along the Zuni River. By about 1720, that was reduced to one. When the American archaeologists arrived, they set about excavating almost every abandoned village they could find. In the process, many pieces of ancient pottery came to light. That's where the names Matsaki Polychrome and Red-on-buff (matte paint on white and red slips, produced from about 1375 CE to about 1700 CE), Kwakina Polychrome (glaze paint on a white slip, produced from about 1325 to about 1400) and Heshotauthla Black-on-red and Polychrome (glaze decorations, produced from about 1275 to about 1400) came from. A primary difference between Kwakina and Heshotauthla designations is the color the inside of the bowl is slipped with. The decorations on both are painted with lead glaze colors and are taken from the same design library, which includes many designs common to the Mogollon Highlands in eastern Arizona (such as St. Johns Polychrome), although the designs tend to be not as well executed.

The advent of Matsaki Polychrome and Red-on-buff coincides with the entrance of an immigrant community from the north: the land of the Hopi. With them came the basic design library of what we now refer to as "Sikyatki Polychrome." Production of Kwakina- and Heshotauthla-style pottery dropped off quickly after the arrival of those who produced the Matsaki styles. It was around that time, too, that the Zuni villages around the Zuni Mountains were abandoned and the people pulled back to the pueblos along the lower Zuni River.

After Spanish contact and conquest, the Zunis were reduced to about one-tenth their population by Spanish diseases and labor practices. Before too long, they were gathered together in one village near the bank of the Zuni River. Their image catalog changed, too. When the American archaeologists and ethnologists came, they removed virtually every artifact of Zuni history they could dig up or find otherwise. Then they spirited it all away to storerooms on either coast, where most of it remains in boxes in dingy basement rooms today.

In 1986, Josephine Nahohai and several members of her family traveled to Washington DC and explored the basement storage shelves of the Smithsonian Institute, copying every ancient Zuni shape and design they found into their notebooks. When they returned to Zuni, their drawings became the basis for many of what are now referred to as traditional Zuni designs. Among those designs are symbols for mountains and forest, and images of frogs, tadpoles, dragonflies, serpents and rainbirds. Other Zuni potters have since visited other storerooms of ancient Zuni pottery and brought drawings of those shapes and designs back to the pueblo, too.

Zuni Pueblo Teaching Tree

Disclaimer: This "teaching tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this group and arrange them in a generational order.

The pottery tradition at Zuni Pueblo almost died out until Daisy Hooee (granddaughter of Nampeyo of Hano, Hopi-Tewa) took on the job of teaching pottery at Zuni High School in 1960. She was recruited for the job by Catalina Zunie, a Zuni potter who had spent several years just trying to get pottery on the school curriculum. Daisy also spent a year working with Catalina to become a consummate Zuni potter herself before she started teaching.

There have been several teachers at Zuni High since then and for some students, learning from their parents (who were former Zuni High students) has helped to strengthen the tradition. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Daisy Hooee Nampeyo taught 1960-1974

- Jennie Laate taught 1974-1990

- Carlos Laate

- Agnes Peynetsa

- Anderson Peynetsa & Avelia Peynetsa

- Anderson Jamie Peynetsa

- Ashley Peynetsa

- Dominic Laweka

- Priscilla Peynetsa & Daryl Westika

- Daria Westika

- Gaylon Westika

- Caylon Westika

- Brian Tsethlikai and Yvonne Nashboo

- Eileen Yatsattie