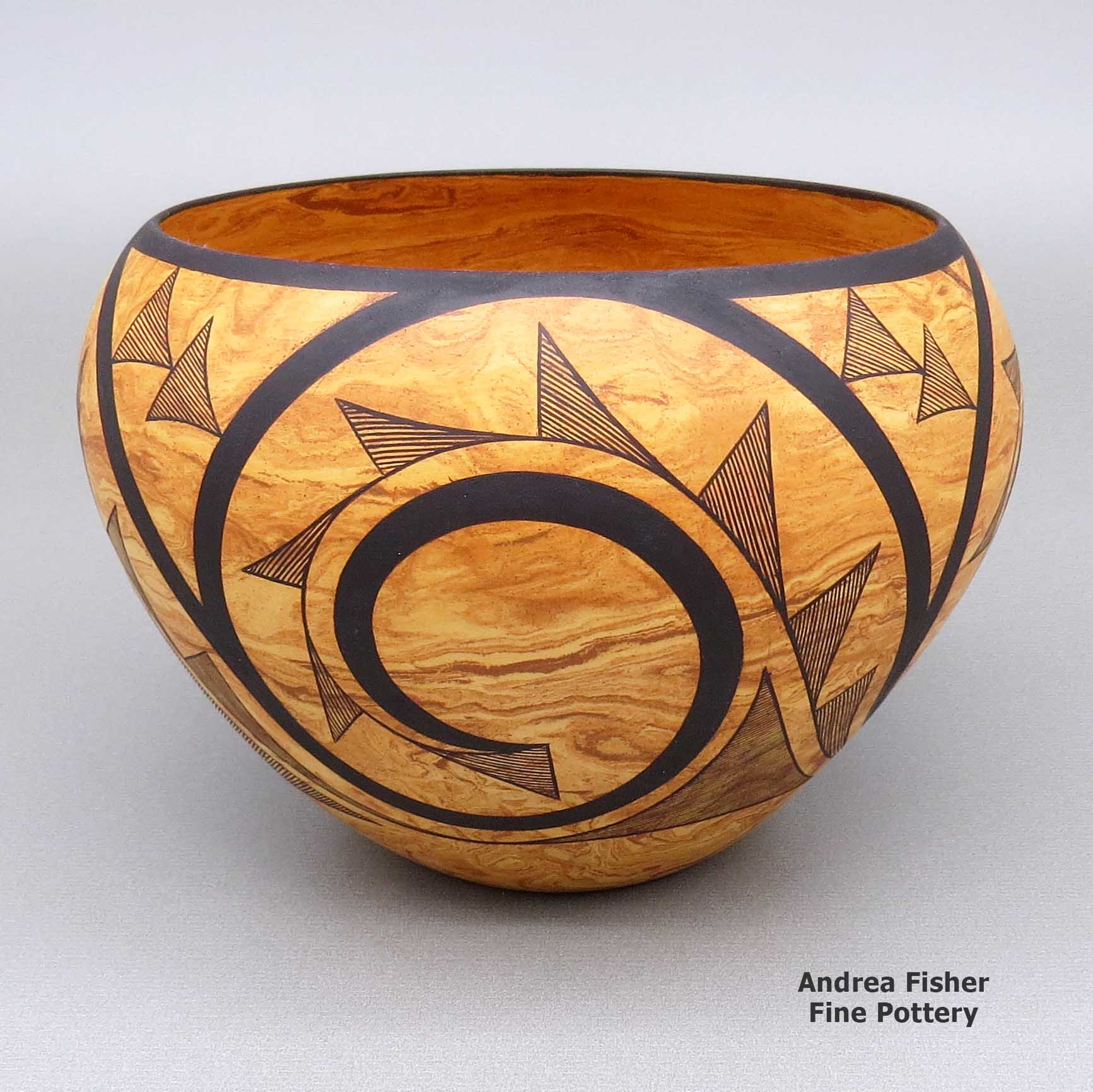

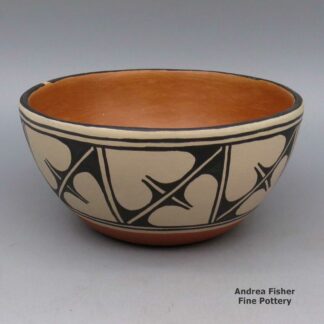

| Dimensions | 5.25 × 5.25 × 4 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | C. Analla Jr. Paguate, N. Mex. Pueblo of Laguna |

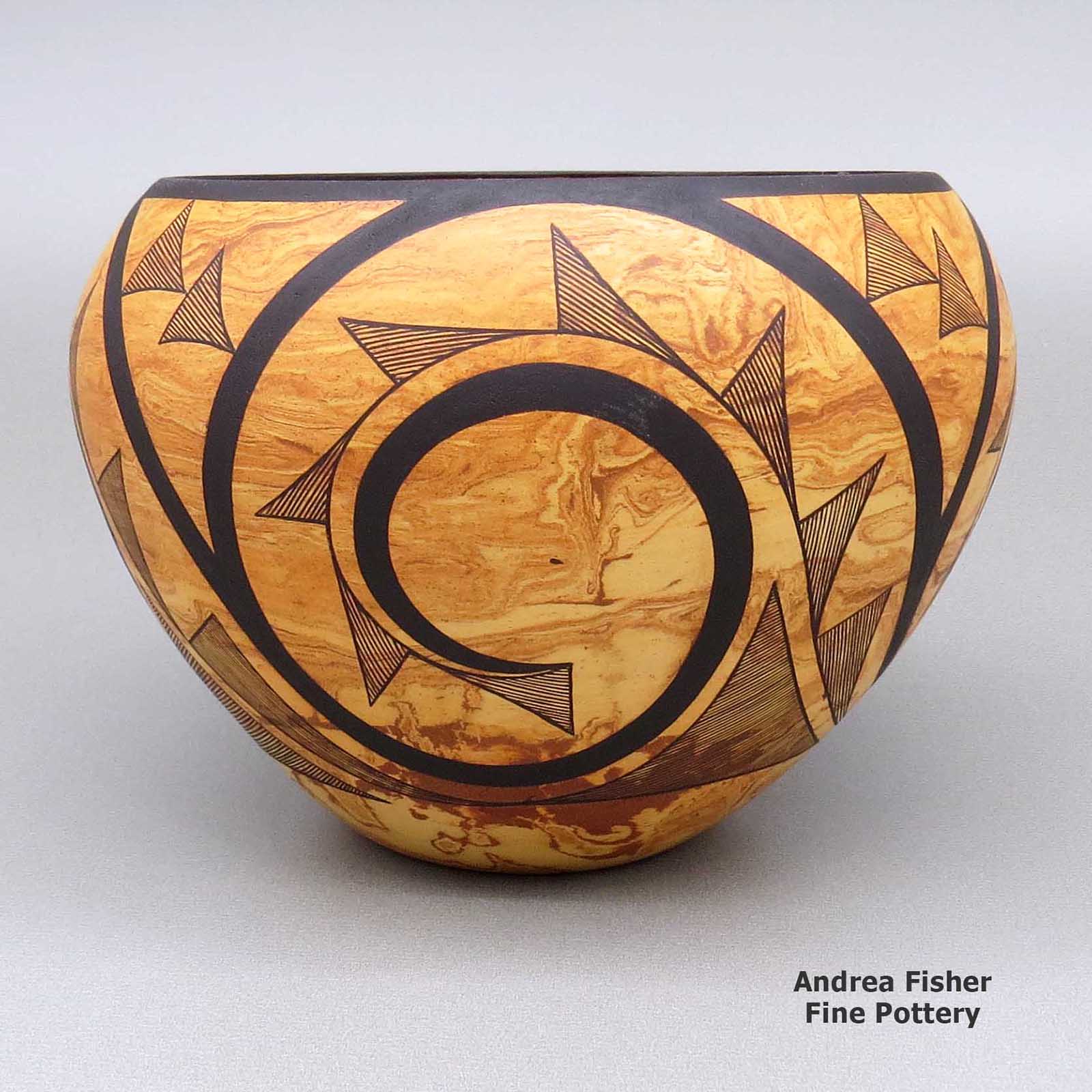

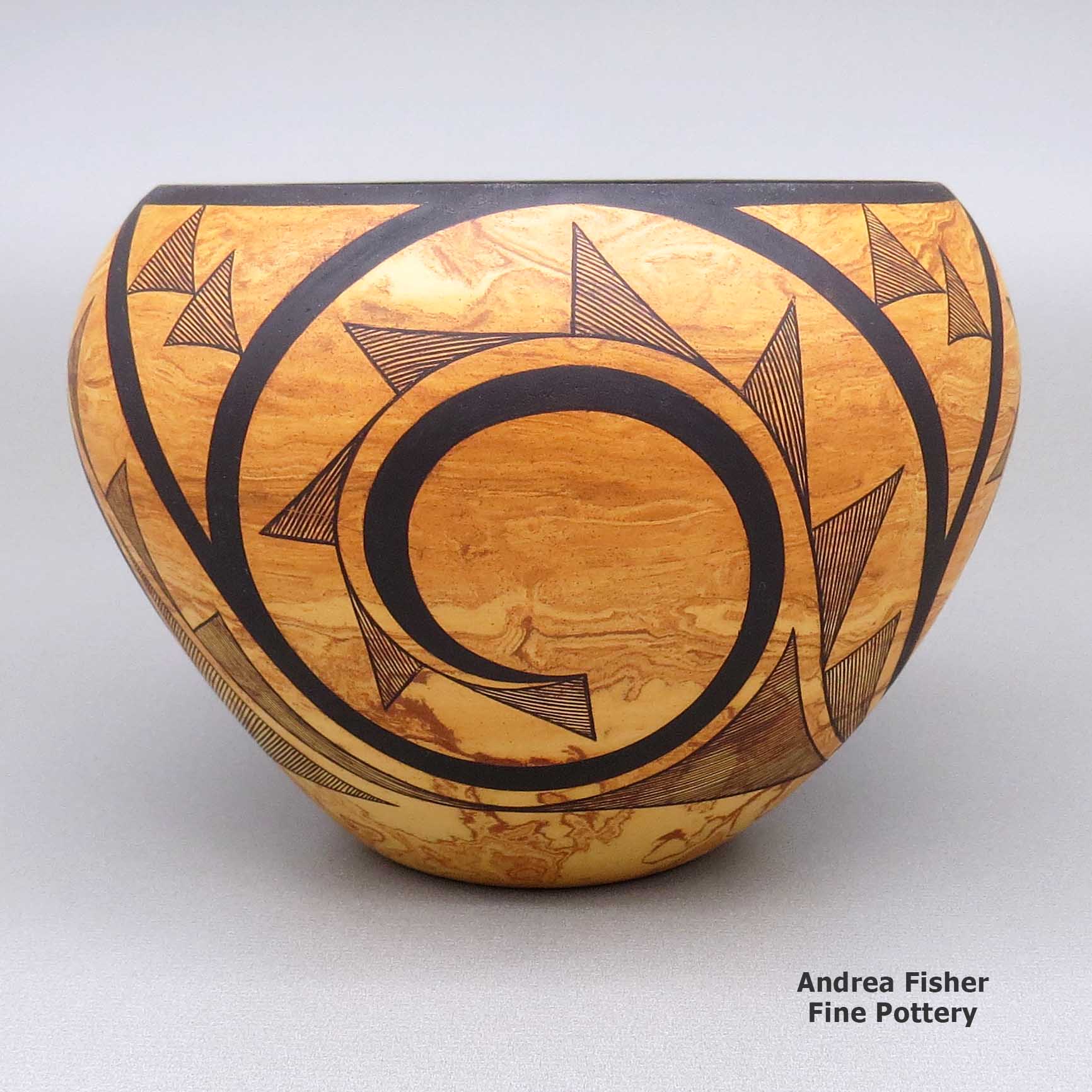

Calvin Analla Jr, zzla3c210, Marbleized clay bowl with a geometric design

$950.00

A marbleized clay bowl decorated in black with a geometric design

In stock

- Product Info

- About the Artist

- Home Village

- Design Source

- About the Shape

- About the Design

- Family Tree

Brand

Analla, Calvin Jr

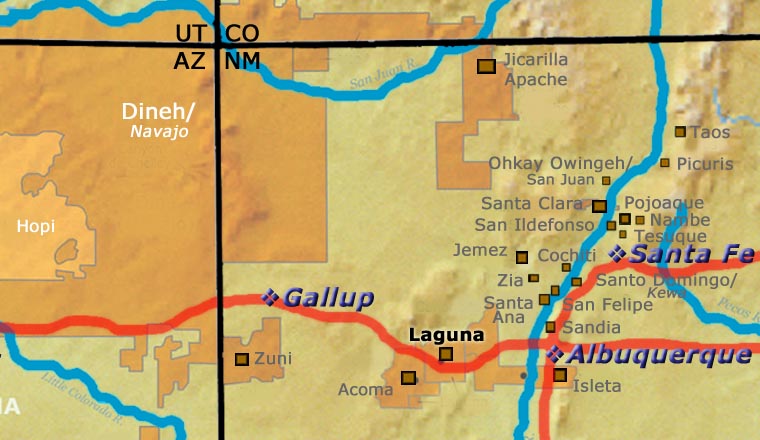

Born in 1958, Calvin Analla Jr. is a traditional Laguna Pueblo potter. He comes from the village of Paguate, about eight miles north of Old Laguna. His father, Calvin Analla Sr., is from Laguna. His mother, Velma Analla, is Dineh.

Born in 1958, Calvin Analla Jr. is a traditional Laguna Pueblo potter. He comes from the village of Paguate, about eight miles north of Old Laguna. His father, Calvin Analla Sr., is from Laguna. His mother, Velma Analla, is Dineh.Calvin began creating his signature style of potting in 1990 while watching and working with his paternal grandmother, Evelyn Cheromiah, and his aunt, Lee Ann Cheromiah.

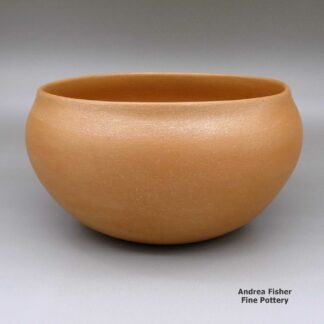

Most of Calvin's clay is harvested from local Laguna sources (some of his clay is from Hopi source) and his pots are molded and shaped using the traditional coil method. Polishing is achieved by rubbing smooth river stones against the damp pottery. What appears to be black paint is processed from cooking wild spinach and mixing the mineral hematite into the residue. The process is completed by firing the pots in red cedar and sheep manure in an in-ground fire pit.

In addition to Evelyn and Lee Ann Cheromiah, Calvin is related to two other famous potters: his sister, Yvonne Analla Lucas, and her husband, Hopi potter Steve Lucas. One day in his workshop Calvin was a bit short of clay and he asked Steve if he could spare a handful.

Calvin's mixing of Hopi clay and his Laguna clay led to what is now Calvin's signature look. His pottery is also distinguished by very thin walls, scalloped rims and fine painted lines with details of sky elements and other ancient Laguna designs.

Calvin has been making his pots for more than 20 years. He's participated in shows at the Heard Museum Guild Indian Art Fair and Market in Phoenix, the Santa Fe Indian Market, the Autry National Center in Los Angeles, The Eiteljorg Musum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis, and the Gallup InterTribal Indian Ceremonial along the way. He's earned a collection of Judge's Choice, First and Second Place ribbons over the years.

Calvin sees his journey as contributing to a new expression for historic Laguna designs through his experiments with techniques and pottery processes.

Calvin says his favorite shapes to make are canteens and jars. He also prefers working with marbleized clay and decorating his creations with ancient Laguna designs.

A Short History of Laguna Pueblo

After the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, many pueblo people were fearful of Spanish reprisals. Spanish militias returned in 1681, 1682, 1685 and again in 1689. That first return brought them as far north as Isleta and that pueblo was attacked, looted and burned. The second return saw troops marching up to Santa Ana and San Felipe, attacking, looting and burning both. In those years, when the Puebloans became aware of approaching Spanish forces they mostly scattered into the mountains and the Spanish found empty villages, easy to loot and easy to burn.

When Don Diego de Vargas marched north in 1692, he was intent on reconquering Nuevo Mexico and re-establishing a long-term Spanish presence there. As the conquistadors who accompanied him were on a "do-or-die" mission, the reconquest took on a tenor quite different from the previous missions...

At first de Vargas followed a path of reconciliation with the pueblos but that was soon replaced with an iron fist that brought on a second revolt in 1696. The pueblos didn't fare so well the second time around and a large number of Pueblo warriors were executed while their wives and children were forced into slavery. When word of de Vargas' actions got back to the King of Spain, he ordered de Vargas banned from the New World. However, most of the damage was already done.

Many modern historians say Laguna Pueblo was established between 1697 and 1699 by refugees seeking to avoid fighting with the Spanish. Many of those refugees had left the first pueblos approached by the Spanish in 1692. First they scattered to more remote places like Acoma, Zuni and Hopi, or to more Spanish-friendly Isleta. However, the pressure of those refugees strained the resources of the other pueblos and quickly forced the refugees to consider starting a new existence in a newly-formed pueblo. The area of Laguna had been settled several hundred years previously by some ancestors of today's tribe. Other ancestors arrived during the periods of great drought that brought the Ancestral Puebloans (Anasazi) down from the Four Corners area to the areas where we now find the Rio Grande Pueblos. Some of the land under Laguna control has also been found to contain archaeological resources dating as far back as 3,000 BCE.

The prehistoric village of Pottery Mound is located just east of today's Laguna Pueblo boundary on Isleta land. Some archaeologists have said that Pottery Mound has more different shapes and forms of pottery and more designs on it than any other pottery center in the Rio Grande area. Pottery Mound was abandoned before the Spanish first arrived but archaeologists have followed the tracks left by Pottery Mound styles, shapes and designs to settlements in the Hopi mesas and the Four Corners area.

Life was relatively quiet at Laguna until the 1860s. That's when the US Government started looking for a southern route to run a railroad across America to the Pacific Coast. The first route chosen ran right across Laguna Pueblo, not far from the village itself. The Marmon brothers, Presbyterian missionaries who were also land surveyors, were sent to Laguna to proselytize and to work as surveyors. Both brothers married prominent women in the pueblo and come 1872, one of them was elected President of Laguna Pueblo. He immediately acted to destroy the remaining kivas on pueblo land. That forced a schism in the tribe and many of the fundamentalists (as in: traditional Lagunas) relocated downstream and built a pueblo with kivas at Mesita.

After more interference from the Christian government at Old Laguna, many of the Mesita folks packed up and headed for Sandia Pueblo. But they chose to travel via Isleta Pueblo and ended up stuck there: Isleta offered them refuge only if they guaranteed their clan ritual masks (and other accoutrements) would remain at Isleta forever. A few years later there were problems at Isleta and some of the Lagunas returned to Mesita while most of the others moved northeast on Isleta land and built a couple of smaller pueblos nearer to the mountains.

Over time, several villages were established in the area around Old Laguna and when the Lagunas were granted their own reservation, they were given about 500,000 acres of land. That made Laguna one of the largest of all pueblos in terms of land. However, today only about half the enrolled members of the tribe live at Laguna as many have been drawn to nearby Albuquerque in search of work.

In the 1950s uranium was discovered on Laguna land and after forcing negotiations with the tribal council, a huge open-pit mine was developed near Paguaté. That provided good-paying jobs for a few years but it also contaminated their water and land with radioactive pollutants. Cleanup happens at a snail's pace but is supposedly ongoing.

Today Laguna operates a number of commercial and industrial enterprises, including the Route 66 Casino and Resort along Interstate 40 on the west bank of the Rio Puerco.

For more info:

Laguna Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Laguna official website

Discovering the Two-Spirit Artistry in the History of the Pueblo Pottery Revival, by Will Roscoe, © Feb. 2017

About Western Keresan Designs

Those of the Western Keres tradition have a plethora of traditional designs. A reason for that is they have occupied a region on the boundary between the Mogollon cultures to the south and the Ancestral Puebloan cultures to the north. And some of them have been living and working in the same place for a thousand years or more. They have also been making and breaking pottery the whole time. The area of Laguna has been more or less populated for a similar amount of time and, when populated, the Lagunas have moved around more than the Acomas.

Because Acoma and Laguna are located in that boundary area between Chaco Canyon influence to the north and Mogollon-Mimbres Valley influence to the south, designs and techniques have been coming and going across the landscape for many years. Over time, broken potsherds covered with multiple designs have fallen to the ground almost everywhere, just waiting to be picked up by someone, have their designs copied and revived, and their most basic constituents ground and mixed with fresh clay and to be reborn as pots again.

In the 1950s, that started happening a lot, potsherds being picked up and their designs revived, that is. Many of those designs have since been traced back to artisans in the Mimbres Valley working before 1150 CE. They had a unique perspective on the birds, animals, insects and people of their world, and used that perspective to draw and paint unique patterns. Many of those patterns are still being recreated on pottery across the Pueblo world, but especially at Acoma and Laguna. Central to the design palette are stories from the adventures of the Twin Warriors. While some Flower World iconography is also present in the Acoma design palette, there is extremely little from the kachina cults of the Hopi and Zuni.

One of the more recent "traditional" Acoma designs is the parrot holding a twig with berries in its claws. Often there is a rainbow above or below the parrot. Parrots are not natural in New Mexico, they had to have been imported. Before about 1450 CE, there was a trade in parrots and macaws through Paquimé to regions in the north. The remains of macaws have been pretty common but the remains of green parrots have only been recovered from three pueblos: Cicuyé, Paquimé and Grasshopper Pueblo in Arizona. The ancient-most Acoma parrot design has a Mimbres/Mogollon heritage while the parrot most painted today looks more like it came from an Amish trader's box. And it likely did.

With the arrival of Spanish colonists in New Mexico, pueblo potters changed their pottery to meet the demands of a new market. Their shapes and designs changed with that. Everything changed again with the arrival of Amish traders with their enameled cookware in the 1850s. The "new" Acoma parrot was pictured on the boxes those pots came in. The parrot came into being around 1880 and has been in use so long now it is considered "traditional."

Pottery was always in production at Acoma but from about 1600 to about 1950, it was heavily influenced by colonial shapes and designs. Eventually, the potters were reduced to producing items for the tourist trade to make ends meet, and that didn't go over so well either. Their own interest in making pottery fell off. Lucy Lewis, Jessie Garcia and Marie Z. Chino started decorating their pieces with their new interpretations of ancient Mimbres, Tularosa and Cibola designs in the 1920s and interest, both outside and inside the pueblo, grew again from there.

Laguna was impacted more heavily by the newcomers. Two Methodist missionaries married women in the pueblo and one of them shortly had himself elected President of the Pueblo. One of the first things he did was order the destruction of all the kivas on Laguna Pueblo land. That caused a schism and many Lagunas relocated to Isleta for a number of years (some of them are still there).

The Southern branch of the Transcontinental Railroad ran across Laguna Pueblo, and offered jobs to many of the men. That essentially ended the making of pottery by most tribal members. Then uranium was discovered under pueblo lands and more men went to work mining for that. Only a couple families passed the traditional knowledge down, until it eventually reached Evelyn Cheromiah. Nancy Winslow, an Anglo woman from Albuquerque, helped Evelyn obtain a grant to teach pottery making on the pueblo and a small revival started from there. Laguna potters, too, work their designs from designs they find on potsherds they find lying on the ground around the old pueblos. Their designs are very much like those of Acoma, usually just with more white space and bolder lines.

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.

Evelyn Cheromiah Family & Teaching Tree - Laguna Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this group and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

Evelyn worked with Nancy Winslow, an Anglo woman from Albuquerque, to set up what became the 1973 Laguna Arts and Crafts Project. At that time, only Evelyn and a couple potters in the village of Mesita were still making Laguna pottery. Those women were teaching their daughters, too, but it was clearly a dying art. Evelyn and Nancy secured enough funding for Evelyn to teach two 4-month sessions of pottery making classes. Both groups were filled to overflowing.

- Evelyn Cheromiah (1928-2013)

- Lee Ann Cheromiah (1954-)

- Brooke Cheromiah

- Mary Cheromiah Victorino (c. 1950's-)

- Wendy Cheromiah Kowemy

- Wendell Kowemy (1972-)

- Josephita Cheromiah

- Elton Cheromiah

- Calvin Analla Jr. (1958-)

- Elsie Chereposy

- Mabel Poncho (c. 1920s-)

- Bertha Riley (niece) & Stuart Riley Sr. (Dineh)

- Marie Kasero