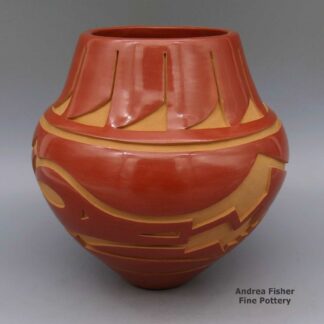

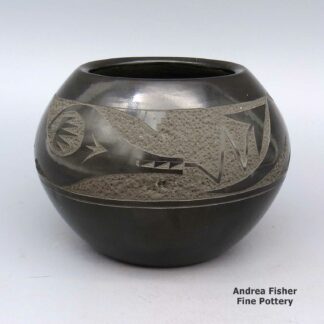

| Dimensions | 3.75 × 5 × 8 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, normal wear |

| Signature | Celes Evelyn Sta Clara Pueblo |

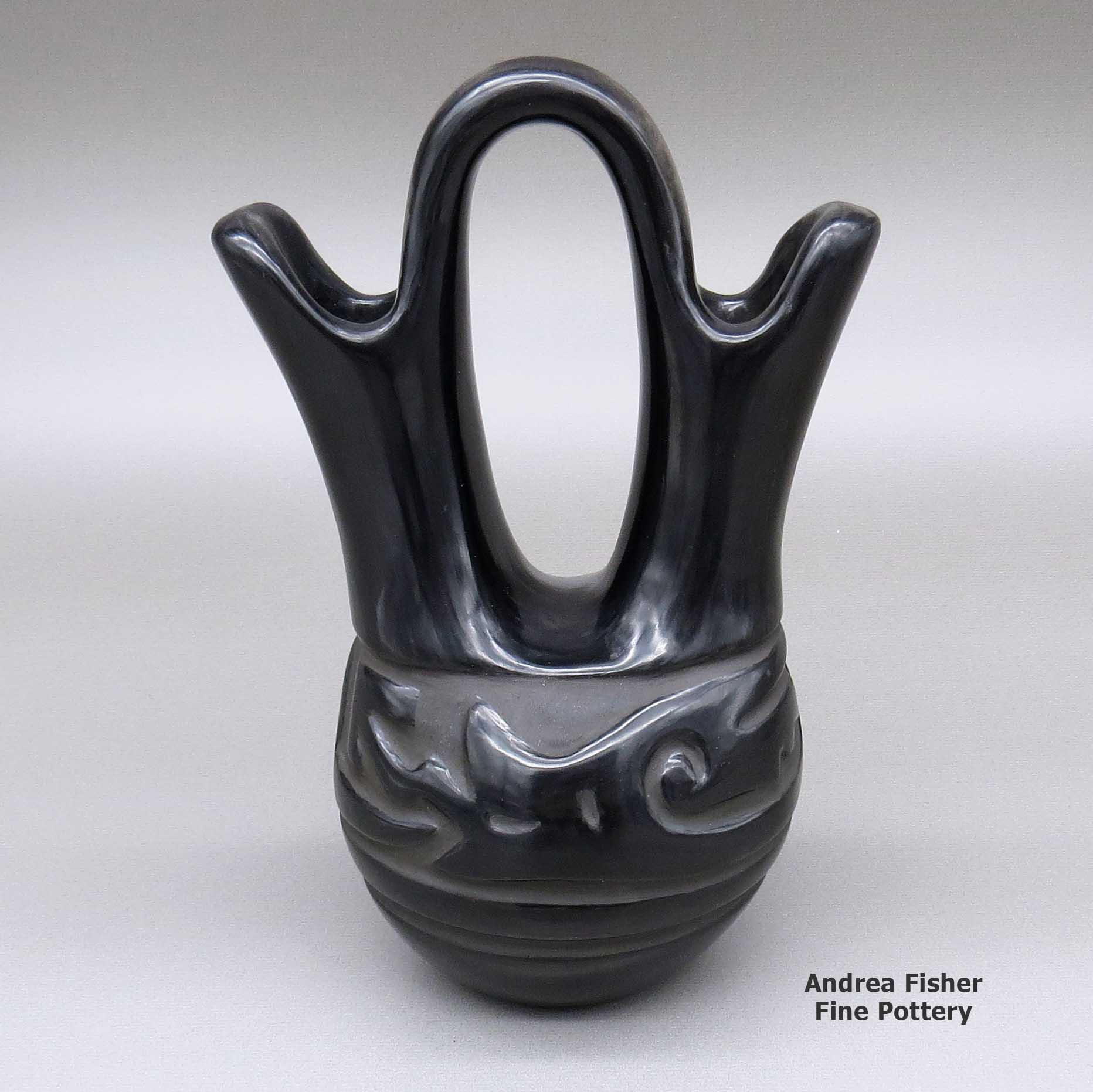

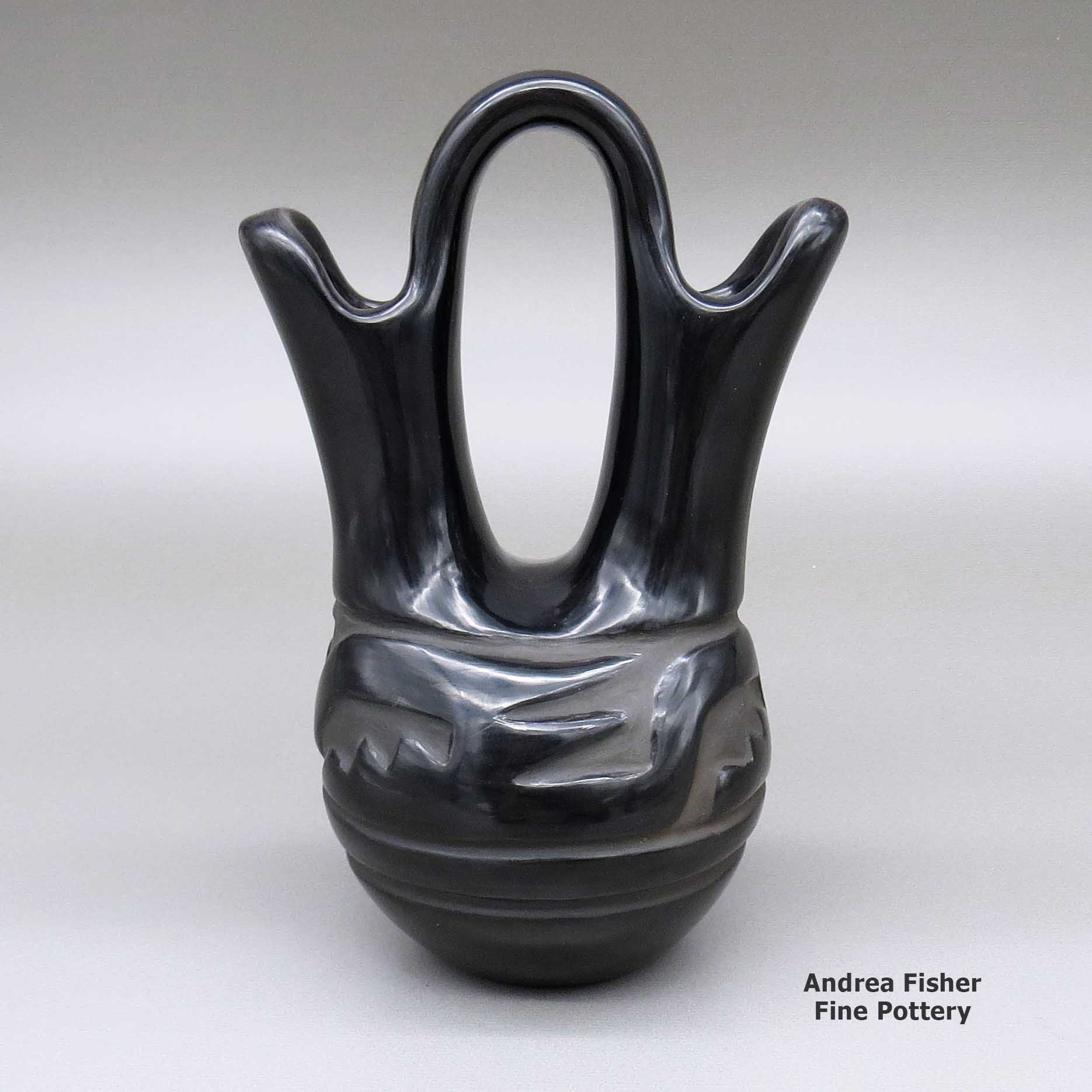

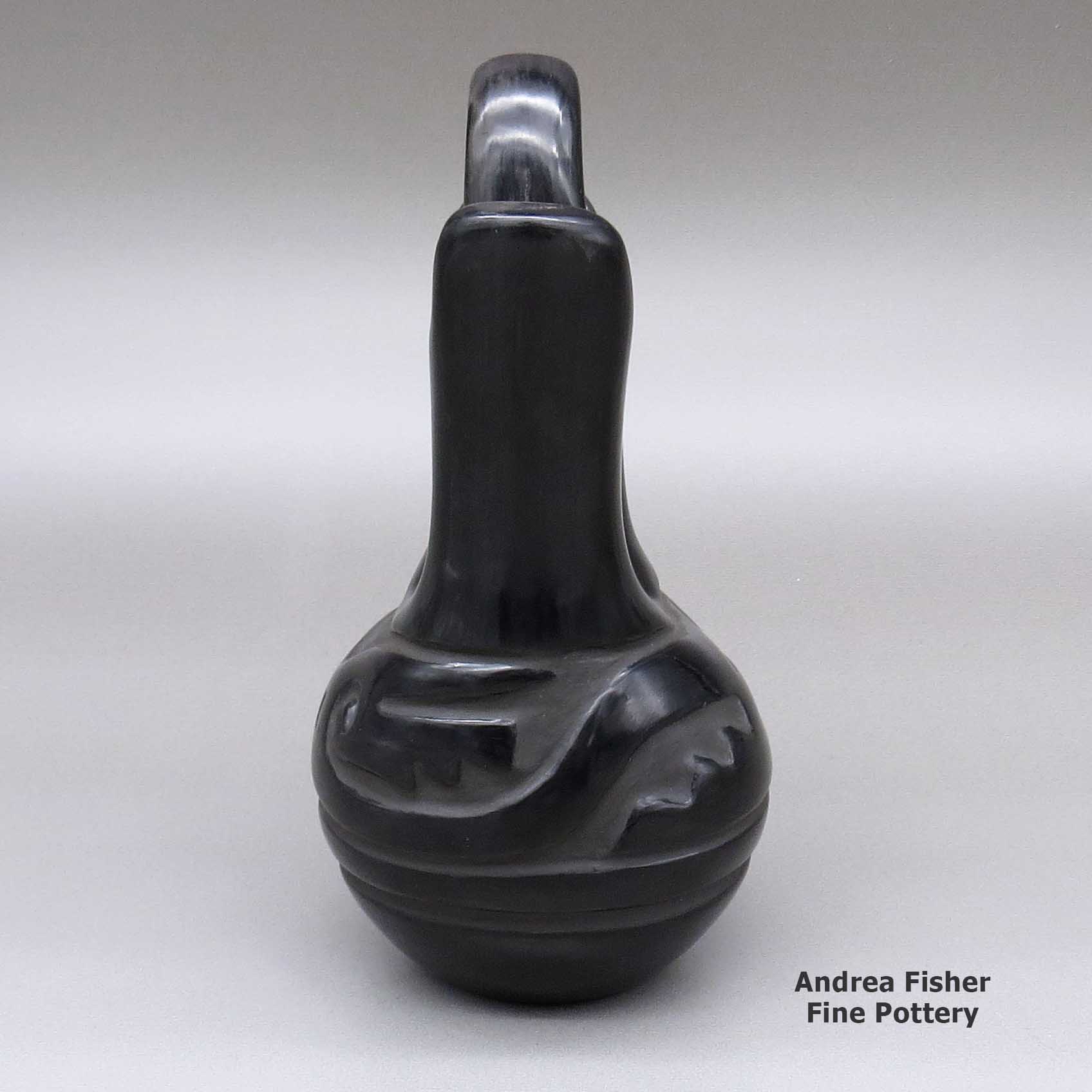

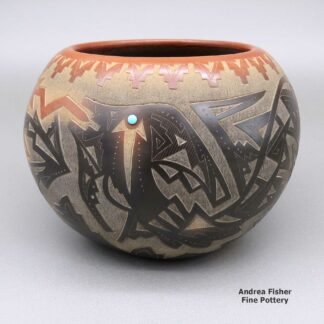

Celes Aguilar, mvsc3b096, Wedding vase carved with an avanyu design

$525.00

A black wedding vase carved around the body with an avanyu design

In stock

Brand

Aguilar, Celes and Evelyn

Celes collaborated with her mother Legoria for many years. They signed their works "Legoria + Celes". After Legoria died, she collaborated with her daughter Evelyn for many more years. They signed their works "Celes/Evelyn".

Celes and Evelyn often made blackware bowls, wedding vases, plates and jars. Their favorite designs to carve seem to have been the avanyu (the mythic Tewa water serpent) and associated geometrics.

Some Awards earned by Celes and Evelyn

- 2001 Santa Fe Indian Market. Class. II - Pottery, Div. C - Traditional pottery, carved or incised, Cat. 1002 - Bowls, Second Place, Evelyn Aguilar with Celes Tafoya

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market. Classification II - Pottery, Div. C - Traditional, Category 1006 - Wedding vases: Third Place, Evelyn Aguilar with Celes Tafoya - Division B - Traditional pottery, Category 905, bowl: Third Place, Evelyn Aguilar with Celes Tafoya

- 1993 Santa Fe Indian Market. Category 1104 - Bowls: First Place, Evelyn Aguilar alone - Category 1105-Wedding Vases: Second Place, Evelyn Aguilar alone

- 1992 Santa Fe Indian Market. Category 1105-Wedding Vases: First Place, Evelyn Aguilar alone

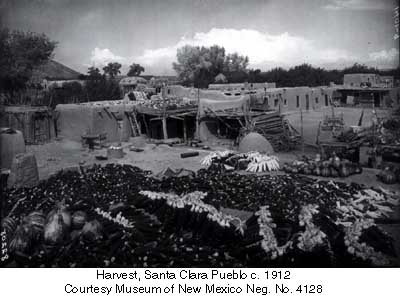

A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

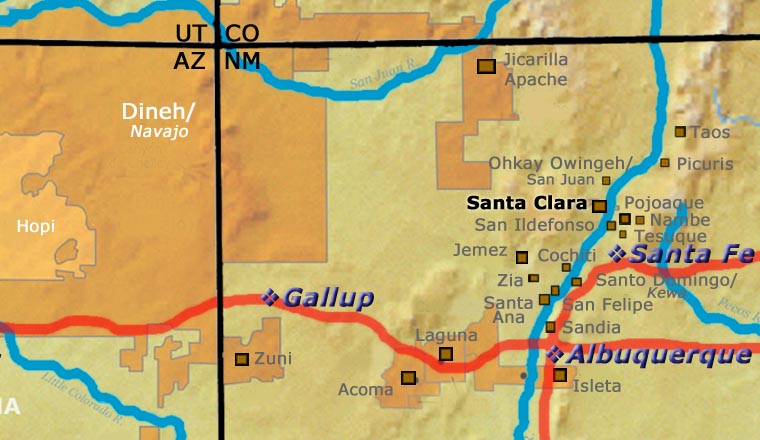

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

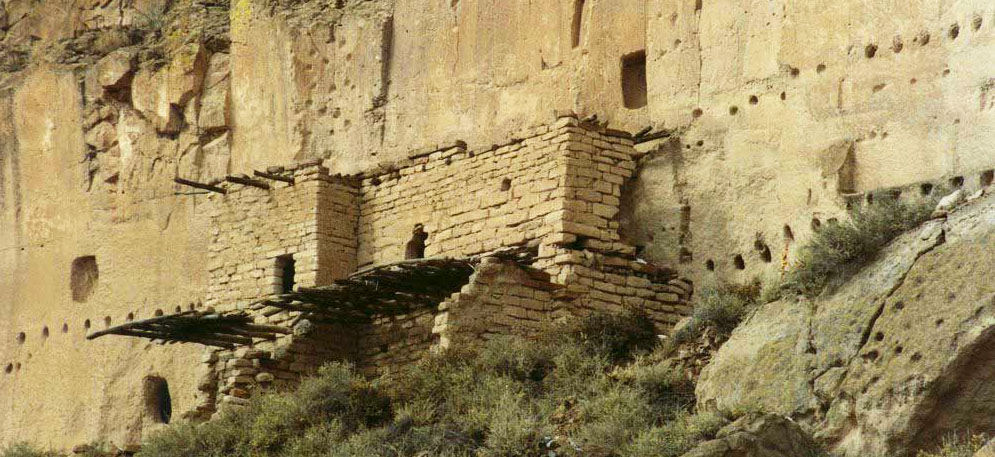

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

The Wedding Vase

- as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Native American wedding ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl’s parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy’s family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy’s home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy’s relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride’s home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom’s relatives and the bride’s parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom’s oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride’s oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom’s necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride’s is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride’s side, and the men from the groom’s.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride’s family feeds all the groom’s relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.

About the Avanyu

The avanyu is a mythical water creature likened to the feathered and plumed serpents of Mesoamerica. The design is primarily part of the design palette of Tewa potters from the Tewa Basin, and even there it varies by pueblo and artist. Wherever the artist is, the avanyu design generally represents the spirit of water rushing through a village after a downpour. The avanyu is also seen as the Keeper of Springs and Guardian of Water. The image is a prayer for rain with the realization of what a downpour can do when it falls on the hard soil of the arid and semi-arid Southwestern deserts.

Artists from San Ildefonso Pueblo generally use an avanyu design with a three-plumed head while Santa Clara Pueblo potters generally use an avanyu with three feathers hanging off the head. The avanyu always has a forked tongue, signifying the lightning bolts that herald its arrival. Some have simplified the design to one feather or plume while others have stylized the design and almost made it cubic or Oriental in design and layout.

Hopi-Tewa potters generally use a somewhat similar Hopi version of a flying, feathered serpent named kwataka. The Zuni version is Kolowisi, although it has been determined that the power of Kolowisi is too much for anyone who is not of Zuni descent so depictions of it have gotten almost as rare as depictions of kwataka.

Marianita Velarde Family Tree - Santa Clara Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Marianita Chavarria Velarde & Herman Velarde

- Jane Baca (1919-2011)

- Kathy Tafoya

- Pamela Starr Tafoya (1951-)

- Velma Tafoya

- Legoria (Velarde) Tafoya (1911-1984) & Pasqual Tafoya

- Celes Velarde Tafoya & Jose Miguel Tafoya

- Evelyn Tafoya Aguilar & Lorenzo Aguilar

- Joyce Tafoya Browning

- Crystal Tafoya

- Emily C. Tafoya

- Gladys A. Tafoya

- Michael A. Tafoya

- Emilio Tafoya

- Sue Tafoya

- Celes Velarde Tafoya & Jose Miguel Tafoya

- Pablita Velarde (painter, pottery painter)

- Helen Hardin (1943-1984)