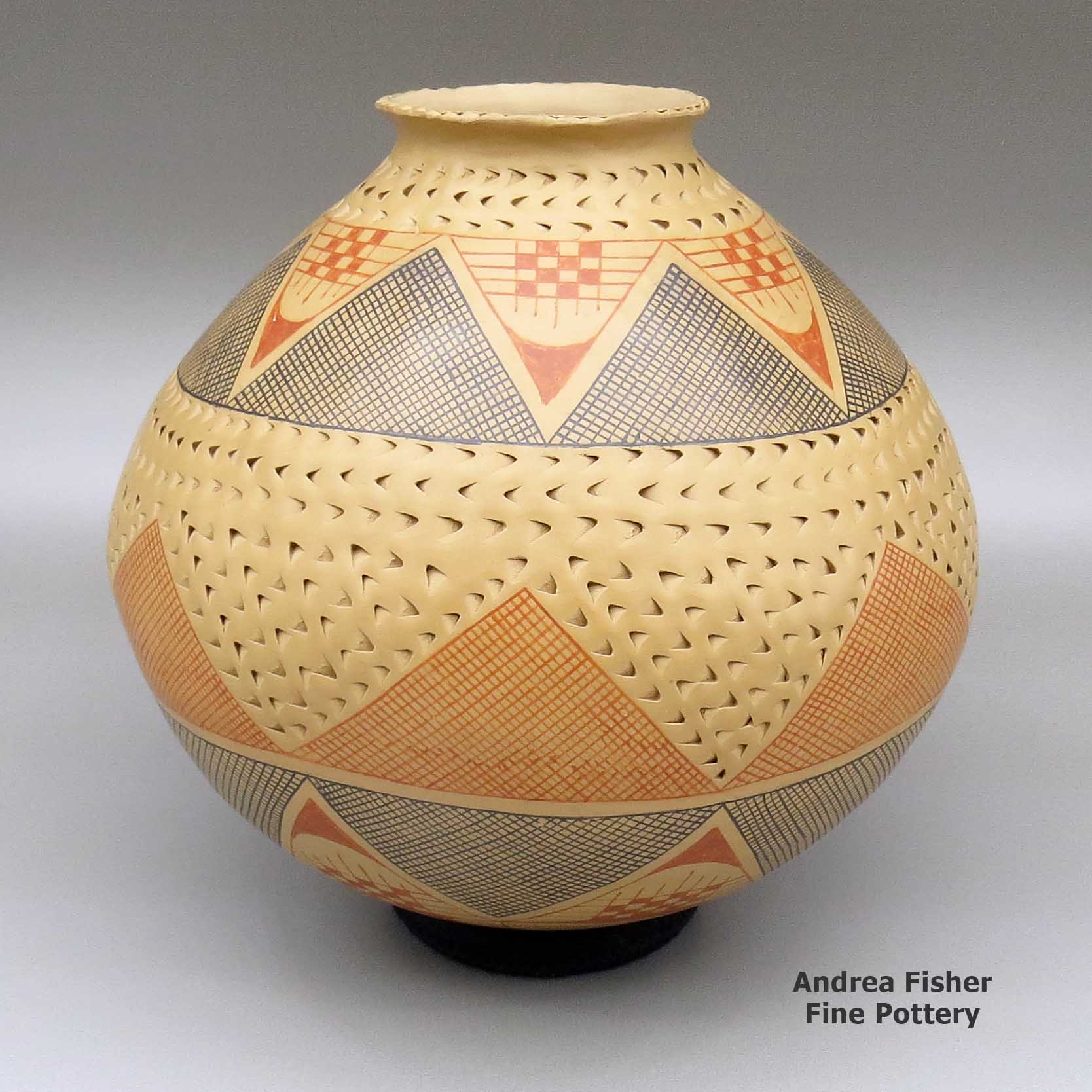

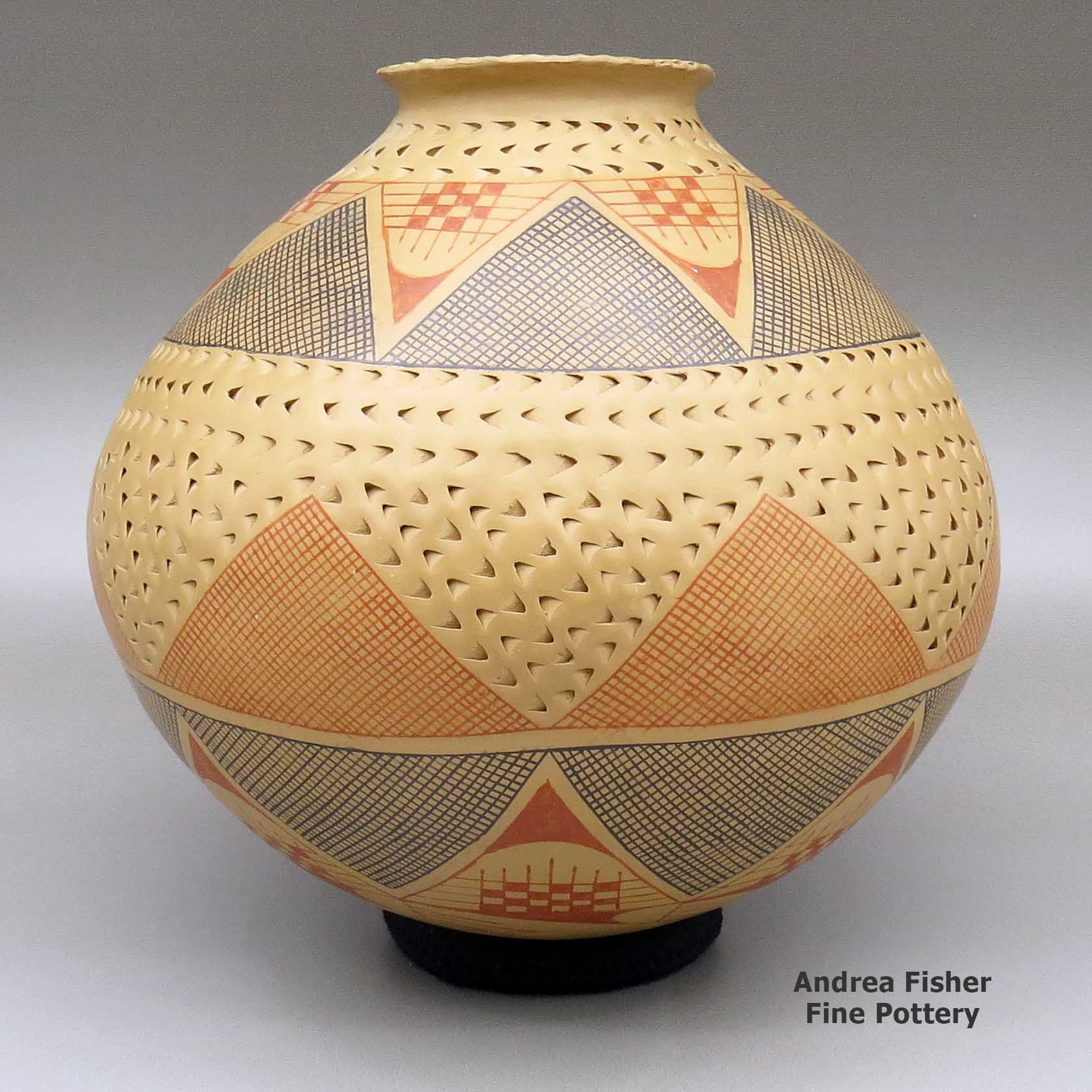

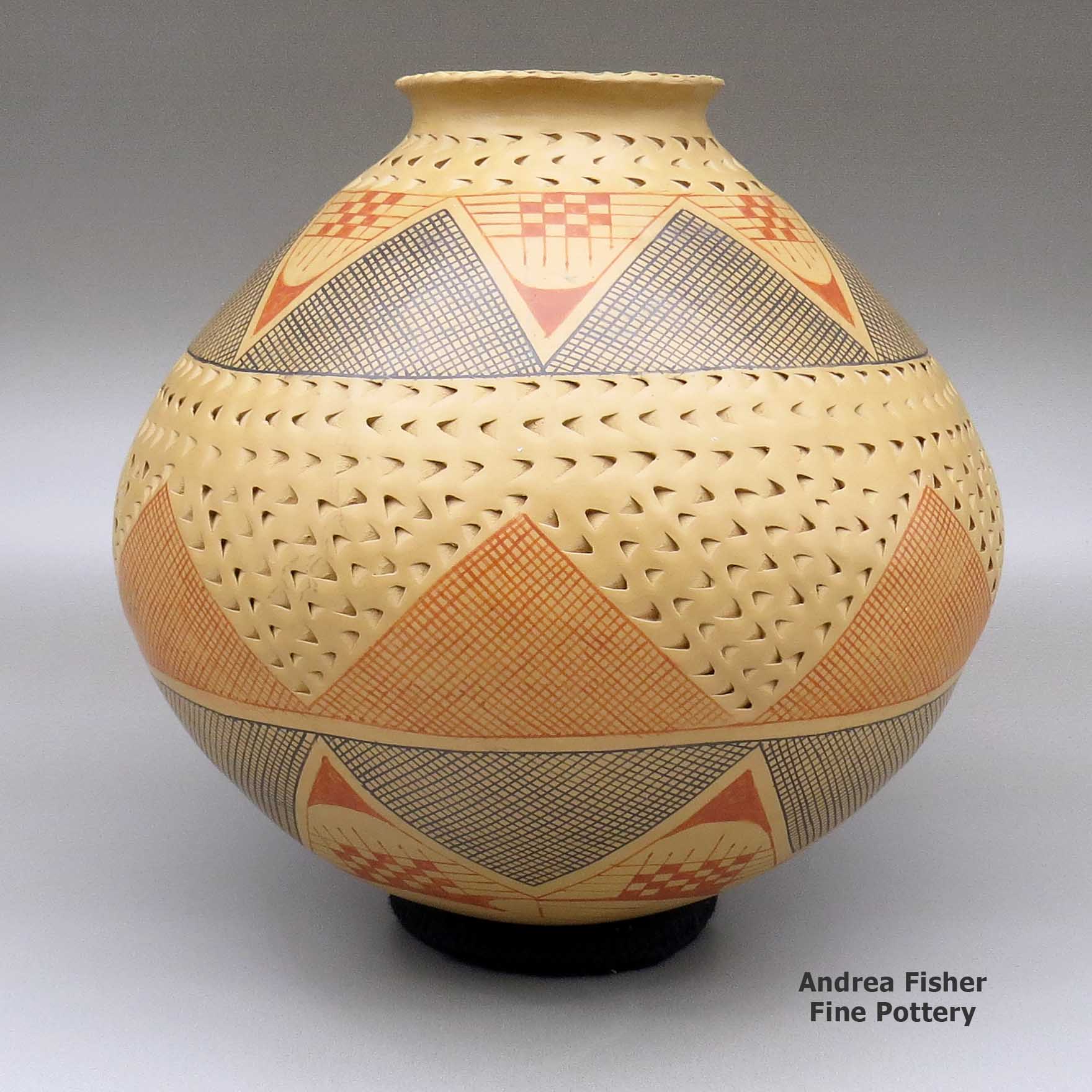

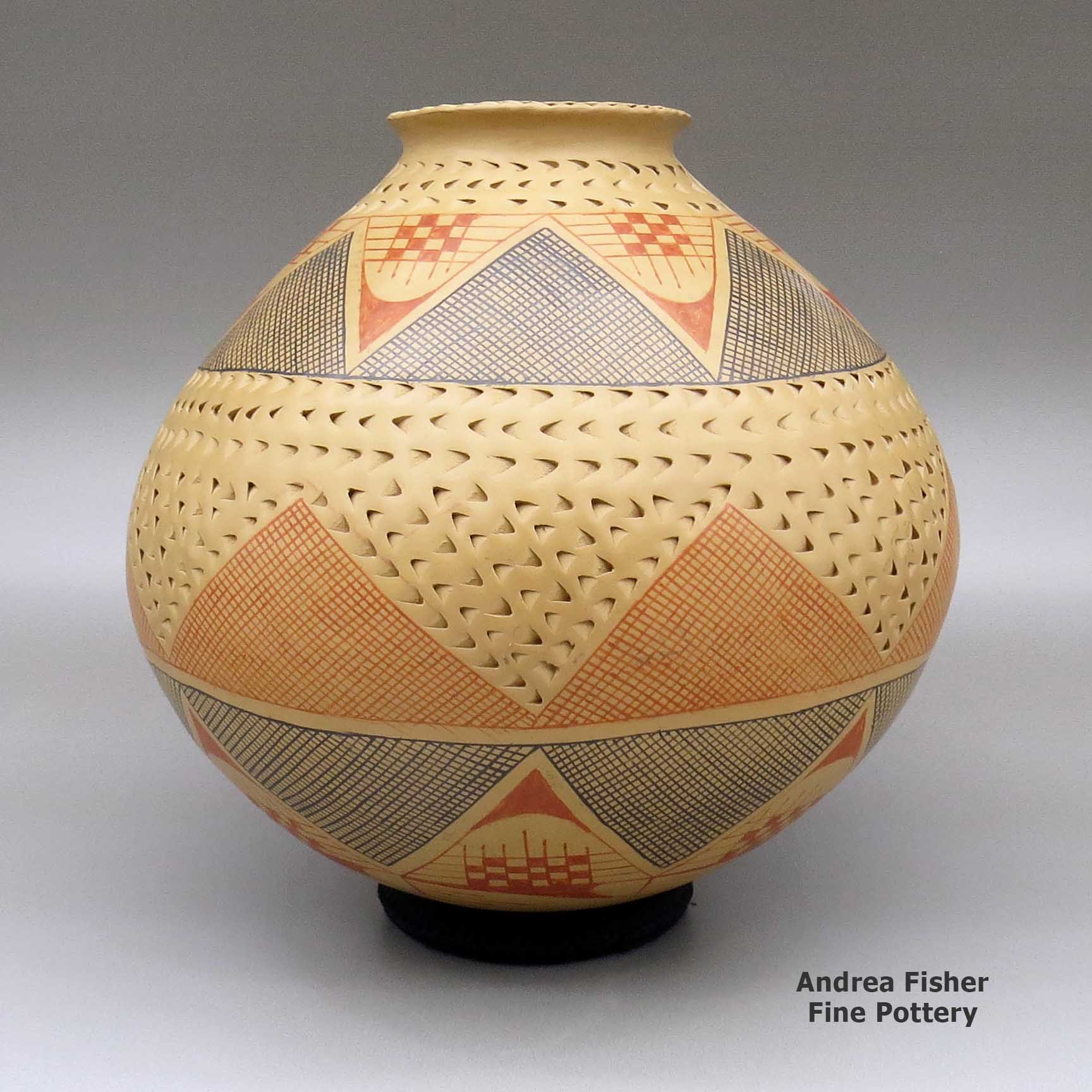

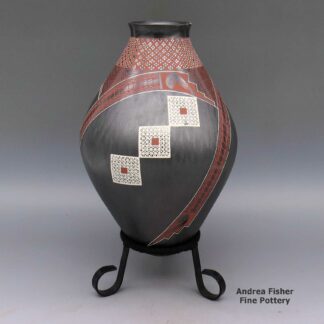

| Dimensions | 10.75 × 10.75 × 10.75 in |

|---|---|

| Measurement | Measurement includes stand |

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has some marks near bottom and on side |

| Signature | Consolacion Quezada |

Consolacion Quezada, thcg3b010, Polychrome jar with a geometric design

$750.00

A polychrome jar with a flared opening and decorated with a corrugated-and-painted cuadrillos and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Quezada, Consolacion

Consolacion usually made large jars and painted them with red and black designs. She taught all her children to make pottery but Mauro, the youngest, has been the most successful as a potter.

Consolacion passed away in Mata Ortiz in 2016.

About Mata Ortiz and Casas Grandes

Mata Ortiz is a small settlement inside the bounds of the Casas Grandes municipality, very near the site of Paquimé. The fortunes of the town have gone up and down over the years with a real economic slump happening after the local railroad repair yard was relocated to Nuevo Casas Grandes in the early 1960s. It was a village with a past and little future.

A problem around the ancient sites has been the looting of ancient pottery. From the 1950s on, someone could dig up an old pot, clean it up a bit and sell it to an American dealer (and those were everywhere) for more money than they'd make in a month with a regular job. And there's always been a shortage of regular jobs.

Many of the earliest potters in Mata Ortiz began learning to make pots when it started getting harder to find true ancient pots. So their first experiments turned out crude pottery but with a little work, their pots could be "antiqued" enough to pass muster as being ancient. Over a few years each modern potter got better and better until finally, their work could hardly be distinguished from the truly ancient. Then the Mexican Antiquities Act was passed and terror struck: because the old and the new could not be differentiated, potters were having all their property seized and their families put out of their homes because of "antiqued" pottery they made just yesterday. Things had to change almost overnight and several potters destroyed large amounts of their own inventory because it looked "antique." Then they went about rebooting the process and the product in Mata Ortiz.

For more info:

Mata Ortiz pottery at Wikipedia

Mata Ortiz at Wikipedia

Casas Grandes at Wikipedia

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Corrugation

Most corrugated pottery is made by coiling a pot but instead of using a piece of gourd (or something with a similar hard, sharp edge) to smooth the coils on the outside, like most other pots, a finger or tool is used to make regular indentations in the coils. Sometimes the coils are smoothed and a tool used to add corrugation to the smooth surface after. Corrugation often covers an entire piece but is also sometimes used in bands to decorate pots in a manner other than painting, carving or etching.

The corrugated pottery pattern was revived by Jessie Garcia after she came across corrugated potsherds lying on the ground near her home at Acoma. They were left over from the work of unknown potters hundreds of years ago.

A corrugated cooking jar offers more surface area to a fire: it heats up faster and the heat distribution is more even. As a design pattern she felt she could make uniquely her own, Jessie spent years perfecting it. Then she taught her daughter, Stella Shutiva, how to make it and Stella perfected it further. Stella even traveled to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC in 1973 to demonstrate how she made her corrugated wares. Then Stella taught her daughter, Jackie Shutiva, how to do it. Today, Jackie is the premier producer of corrugated pottery at Acoma, and she, too, has developed her own styles and forms.

Juan Quezada Family and Teaching Tree - Mata Ortiz

Disclaimer: This "family and teaching tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this grouping and arrange them in a generational order/order of influence. Complicating this for Mata Ortiz is that everyone essentially teaches everyone else (including the neighbors), so it's hard to get a real lineage of family/teaching. The general information available is scant. This diagram is subject to change as we get better info.

- Juan Quezada Sr. (1940-2022) & Guillermina Olivas Reyes (1945-)

- Nicolas Quezada (1947-2011) & Maria Gloria Orozco

- Elida Quezada & Ramon Lopez

- Jose Quezada (1972-) & Marcela Herrera

- Leonel Quezada Talamontes (1977-2014)

- Reynaldo Quezada & Monserat Treviso

- Lucia Quezada

- Lupita Quezada & Hector Quintana

- Maria de los Angeles Quezada

- Maria Guadalupe Quezada

- Mariano Quezada Treviso & Rocio de Quezada

- Maria Acosta

- Fernando Andrew

- Octavio Andrew (1970-)

- Jose Cota

- Gloria Lopez

- Rosa Lopez

Rosa and Gloria's students:

- Roberto & Angela Banuelos

- Adriana Banuelos

- Diana Laura Banuelos

- Mauricio Banuelos

- Olga Quezada & Humberto Ledezma

- Roberto & Angela Banuelos

- Lydia Quezada & Rito Talavera

- Moroni Quezada (1993-)

- Pabla Quezada

- Consolacion Quezada & Guadalupe Corona Sr.

- Dora Quezada

- Guadalupe Lupe Corona Jr.

- Hilario Quezada Sr. & Matilde Olivas de Quezada

- Mauro Quezada (1968-) & Martha Martinez de Quezada

- Avelina Corona & Angel Amaya

- Mauro Corona

- Luis Baca & Carmen Fierro

- Avelina Corona & Angel Amaya

- Oscar Corona Quezada

- Octavio Gonzalez Camacho (Quezada)

- Oscar Gonzales Quezada Jr.

- Guadalupe Lupita Cota

- Reynalda Quezada & Simon Lopez

- Samuel Lopez Quezada (1972-) & Estella S. de Lopez

- Olivia Lopez Quezada & Hector Ortega

- Yolanda Lopez Quezada

- Rosa Quezada

- Noelia Hernandez Quezada (1975-)

- Paty Quezada

- Jesus Quezada

- Imelda Quezada

- Jaime Quezada

- Jose Luis Quezada Camacho

- Mary Quezada

- Genoveva Quezada & Damian Escarcega

- Damian Quezada & Elvira Antillon

- Anjelica Escarcega

- Ana Trillo

- Yesenia Escarcega

- Ivona Quezada

- Miguel Quezada

- Damian Quezada & Elvira Antillon

- Alvaro Quezada

- Arturo Quezada

- Efren Quezada

- Juan Quezada Jr. & Lourdes Luli Quintana de Quezada

- Laura Quezada

- Maria Elena Nena Quezada de Lujan

- Alondra Lujan Quezada

- Mireya Quezada

- Noe Quezada & Betty Quintana de Quezada

- Guillermina Quezada Quintana

- Ivan Quezada Quintana

- Lupita Quezada Quintana

- Taurina Baca (1961-)

- Gerardo Cota

- Guadalupe Gallegos

- Ivonne Olivas

- Manuel Manolo Rodriguez Guillen (1972-)