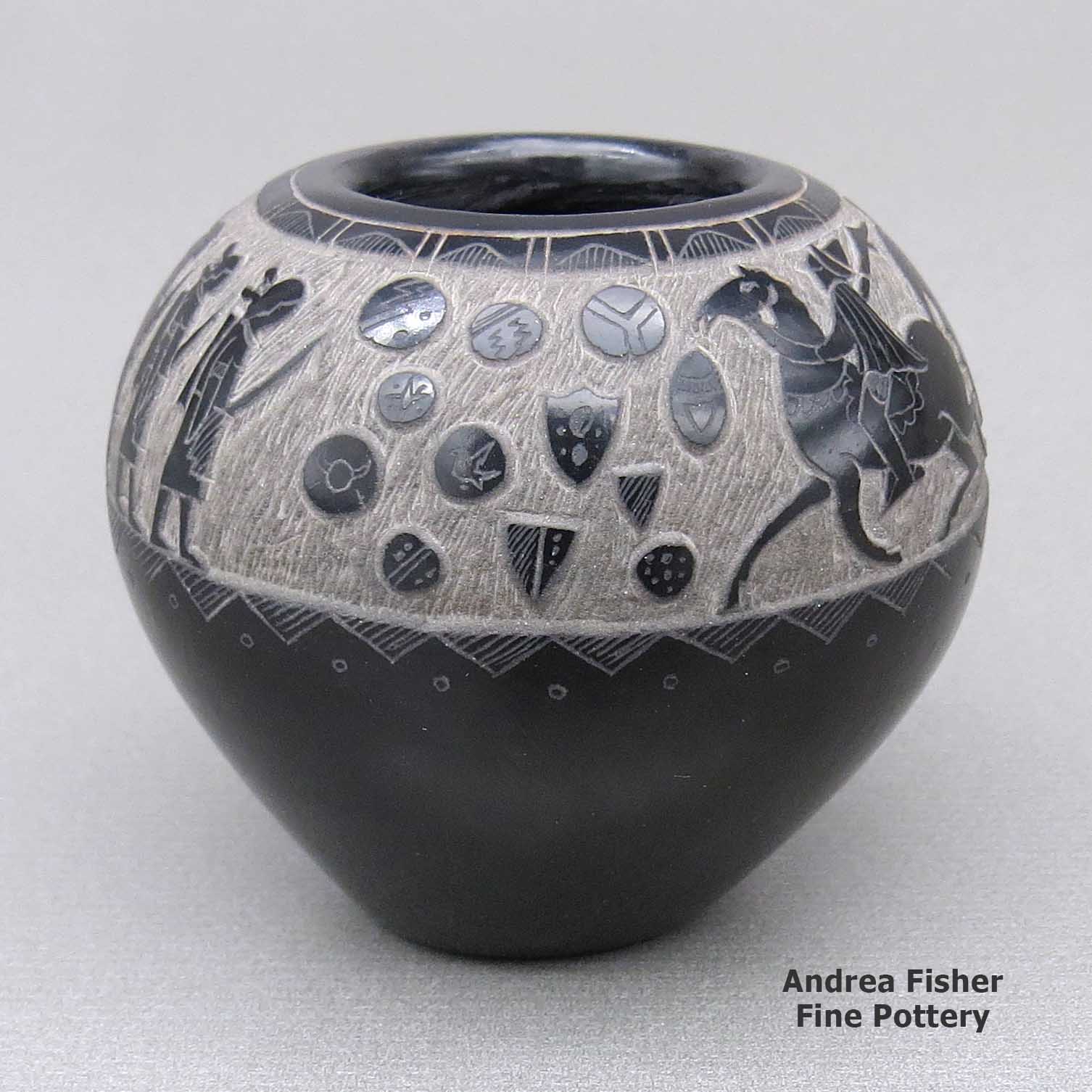

| Dimensions | 2 × 2 × 2 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Goldenrod |

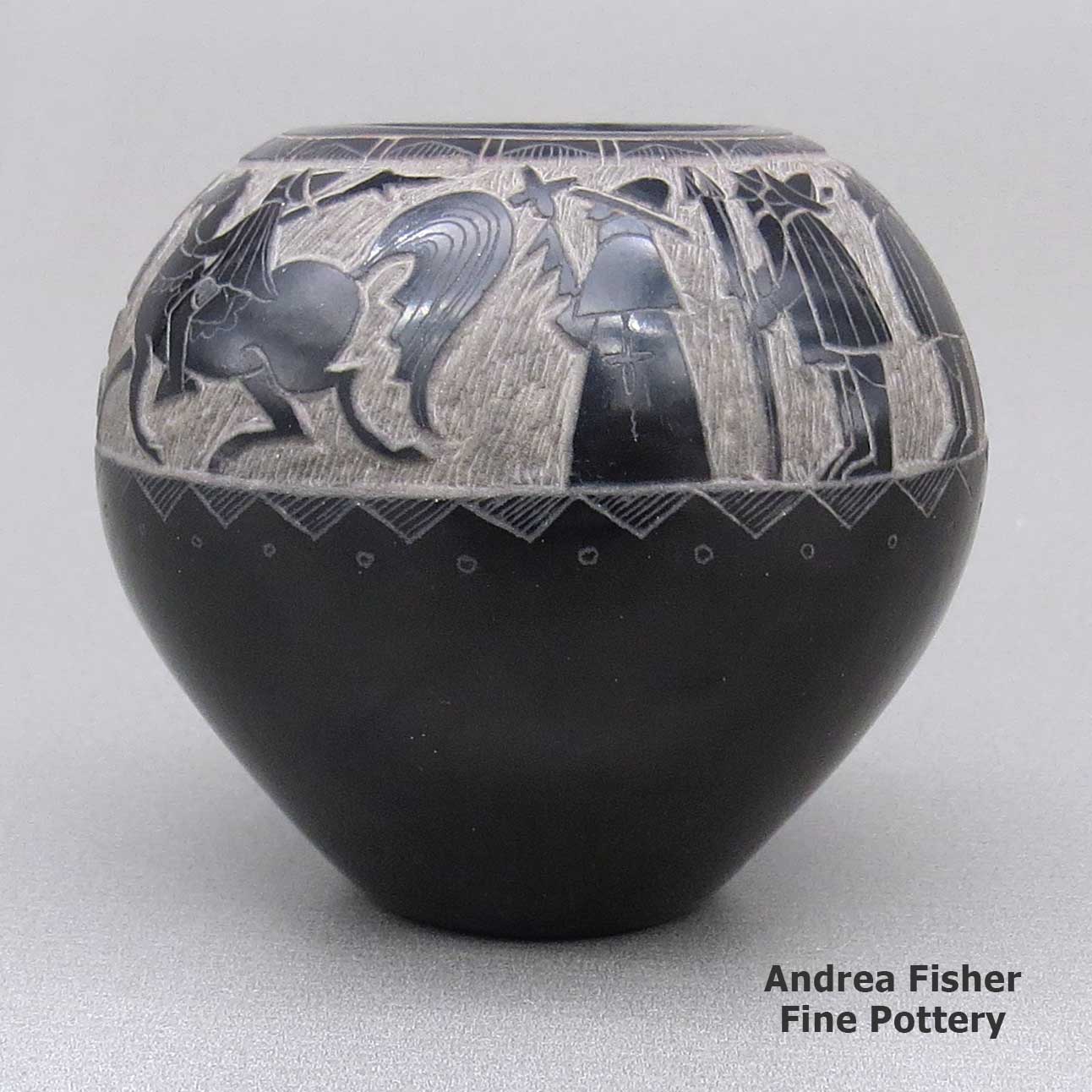

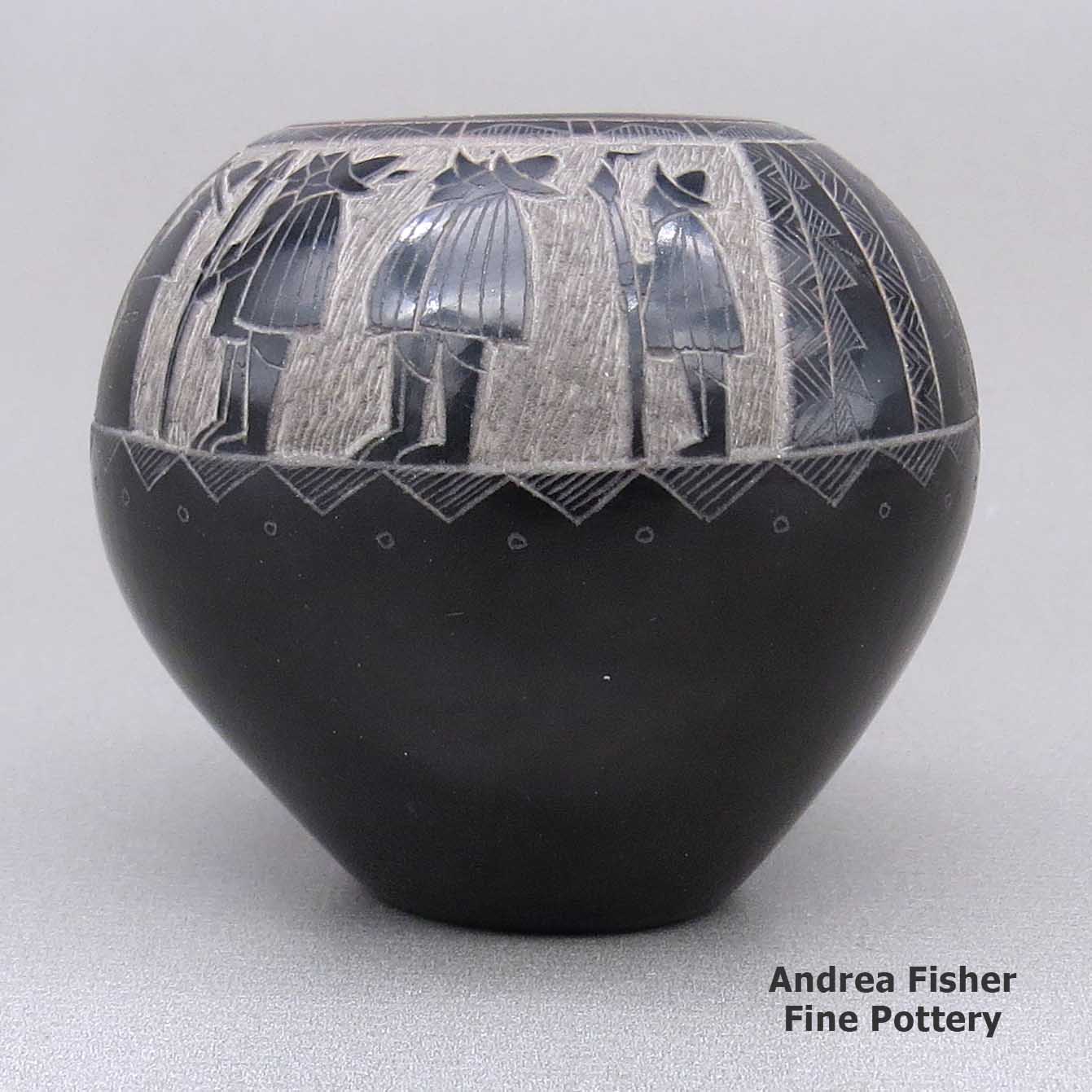

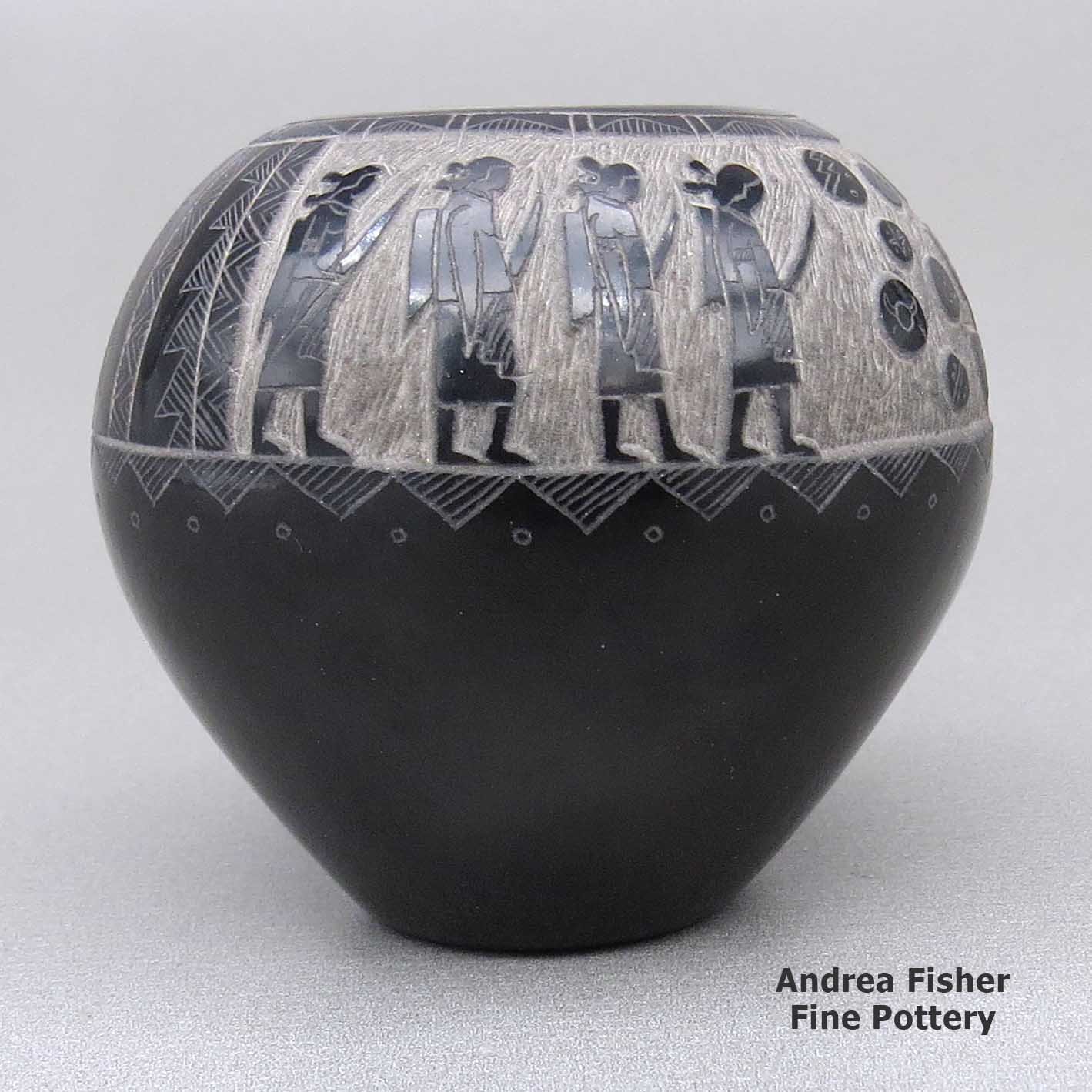

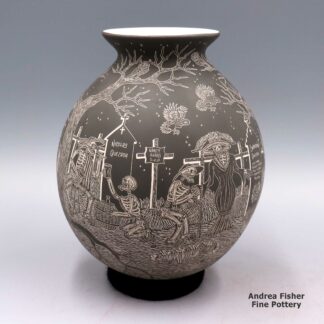

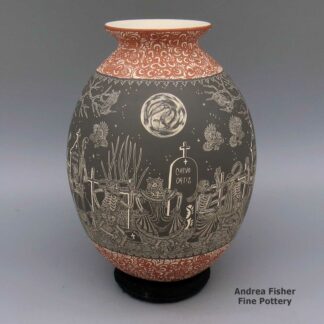

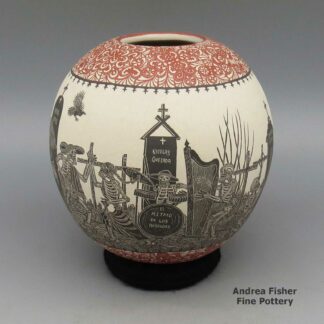

Goldenrod, nmsc3a051, Small black jar with sgraffito design

$525.00

A miniature black bowl decorated with a sgraffito Spanish conquistador and missionary, a Pueblo warrior, and a geometric design

In stock

Brand

Goldenrod

In 1942 World War II was on and Pojoaque Pueblo had been reestablished less than 10 years before. Living conditions were pretty rough and there was little infrastructure in place. When the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1933 asked for information on where to find the Pojoaque people, many of them came out of Santa Clara. Those families had left Pojoaque during a smallpox epidemic when the Cacique (the pueblo's religious leader) died and the last Pueblo Governor left the area for work in Colorado, around 1908.

At Santa Clara, Petra's children grew up surrounded by a vibrant artist community and they learned to make pottery from some of the greats. Eventually, Thelma chose to move back to Pojoaque Pueblo after marrying Joe Talachy while Goldenrod and the others stayed at Santa Clara.

Today, Goldenrod freehand etches (sgraffito style) her hand-coiled seed pots with designs that often feature buffalo, corn maidens, rain clouds, deer, bear paws and birds. She earned First Place and Best of Division ribbons at Santa Fe Indian Market three years after she began making pottery.

Goldenrod's work has been featured in exhibitions all across the country. She was a participant at Santa Fe Indian Market for more than 20 years, earning more ribbons almost every year. The Smithsonian's permanent collection features some of her work. The Heard Museum says that Goldenrod has been an exhibitor at their annual Indian Arts Fair and Market every year since 2010.

Some Exhibits that Featured Goldenrod's Work

- Gifts from the Community. Heard Museum West. Surprise, Arizona. April 12 - October 12, 2008

- Choices and Change: American Indian Artists in the Southwest. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, Arizona. June 20, 2007 - April 2012

- Images, Artists, Styles: Recent Acquisitions from the Heard Museum Collection. Heard Museum North. Scottsdale, Arizona. July 2001 - January 2002

Some Awards Goldenrod has Earned

- 2020 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: Second Place. Awarded for artwork: "Wolves"

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Pottery miniatures not to exceed three (3) inches at its greatest dimension: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Black Bears"

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, hand built, figurative: Second Place

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G Miniatures not to exceed 3": First Place

- 2011 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division G - Miniatures: Second Place. Shared with Preston Duwyenie 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division K - Pottery miniatures, 3" or less in height or diameter, Category 1706 - Sgraffito: Third Place

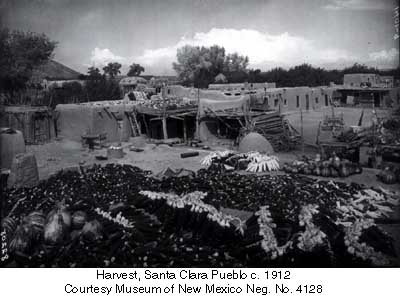

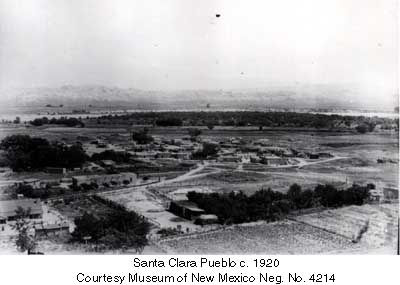

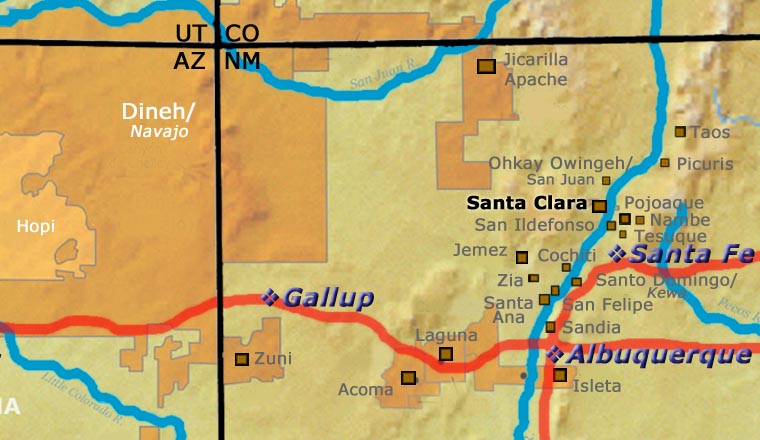

A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

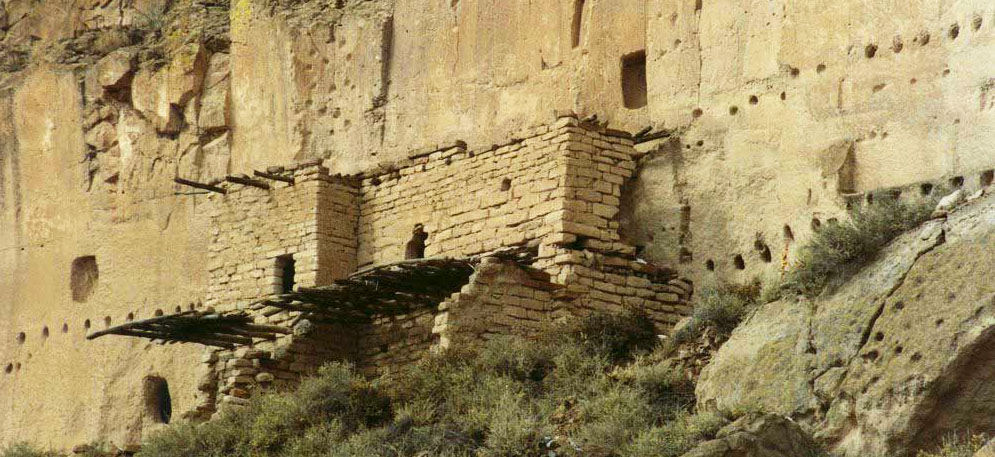

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Sgraffito Designs

"Sgraffito" is from the Italian, meaning "to scratch." It's a technique wherein designs are scratched into the surface of a piece of pottery, generally with the use of a needle, dental tool or other sharp object. Also usually, the surface of the piece has been slipped with one color of clay and scratching through it reveals the design in a different color of clay. Some potters will slip a piece with layers of various colors of clay and the depth of their etching gives a color depth to their designs. Some will fire their pieces first, using the firing process to produce different effects in the clay. When they etch them after, the different depths they etch to also lend a color depth to their designs.

The sgraffito technique has been widely used in Europe for centuries but only came to the pueblos in the late 1960s. Even then, it's only really been developed at Jemez, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso and Ohkay Owingeh. At Santa Clara, Joseph Lonewolf and his father, Camilio Tafoya, and sister, Grace Medicine Flower, have been credited as being among the first to develop sgraffito. Corn Moquino was there, too, in those early days. At San Ildefonso, Juan Tafoya and Barbara Gonzales were among the first. At Ohkay Owingeh, Alvin Curran and Tom Tapia were among the first. Juanita Fragua was among the earliest at Jemez.

In Mata Ortiz, virtually anything goes and sgraffito has been widely used since the early 1970s. Again, some potters scratch their designs before firing, some after. Some scratch to add textured designs to an otherwise same-colored surface. Some carve and scratch and then fire. Some carve, paint and fire, then scratch... The tools they use vary from dental picks and exacto knives to nails, file handles and sharpened bicycle spokes.

Pasqualita Tani Gutierrez Family Tree - Santa Clara Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

Pasqualita Tani Gutierrez was the younger sister of Sarafina Tafoya. Their mother died shortly after Pasqualita was born and she grew up in Sarafina's home, alongside nieces Christina Naranjo, Margaret Tafoya and Dolorita Padilla, and nephew Camilio Tafoya.

- Pasqualita Tani Gutierrez Tafoya (1883-) & Severiano Tafoya

- Petra Montoya (Pojoaque, 1907-1992) & Juan Isidro Gutierrez (Santa Clara, 1901-1977)

- Gloria Goldenrod Garcia & John Garcia

- Desiderio Star Gutierrez & Genevieve Tafoya

- Debra Duwyenie & Preston Duwyenie (Hopi)

- Judy & Andrew Harvier

- Lois Gutierrez (1948-) & Derek de la Cruz

- Juan de la Cruz

- Thelma (1946-) & Joe Talachy (1940-)(San Juan/Ohkay Owingeh)

- Maria Minnie Vigil (1931-)

- Virginia Gutierrez (daughter-in-law of Petra, Nambe/Pojoaque)

- Gloria Goldenrod Garcia & John Garcia

- Tomacita Gutierrez Tafoya (1896-1977) & Cruz Tafoya (1889-1938)

- Cresencia Tafoya (1918-1999)

- Annie Baca (1941-)

- Pauline Martinez (1950-) & George Martinez (San Ildefonso) (1943-)

- Harriet Tafoya (1949-) & Elmer Red Starr (Sioux) (1937-)

- Ivan Red Starr (1969-1991)

- Norman Red Star (nephew) (1955-)

- Cresencia Tafoya (1918-1999)

- Maria Barbarita Naranjo & Jose Dolores Naranjo

- Mary Scarborough

- Veronica Naranjo

- Celestina Naranjo & Salvador Naranjo