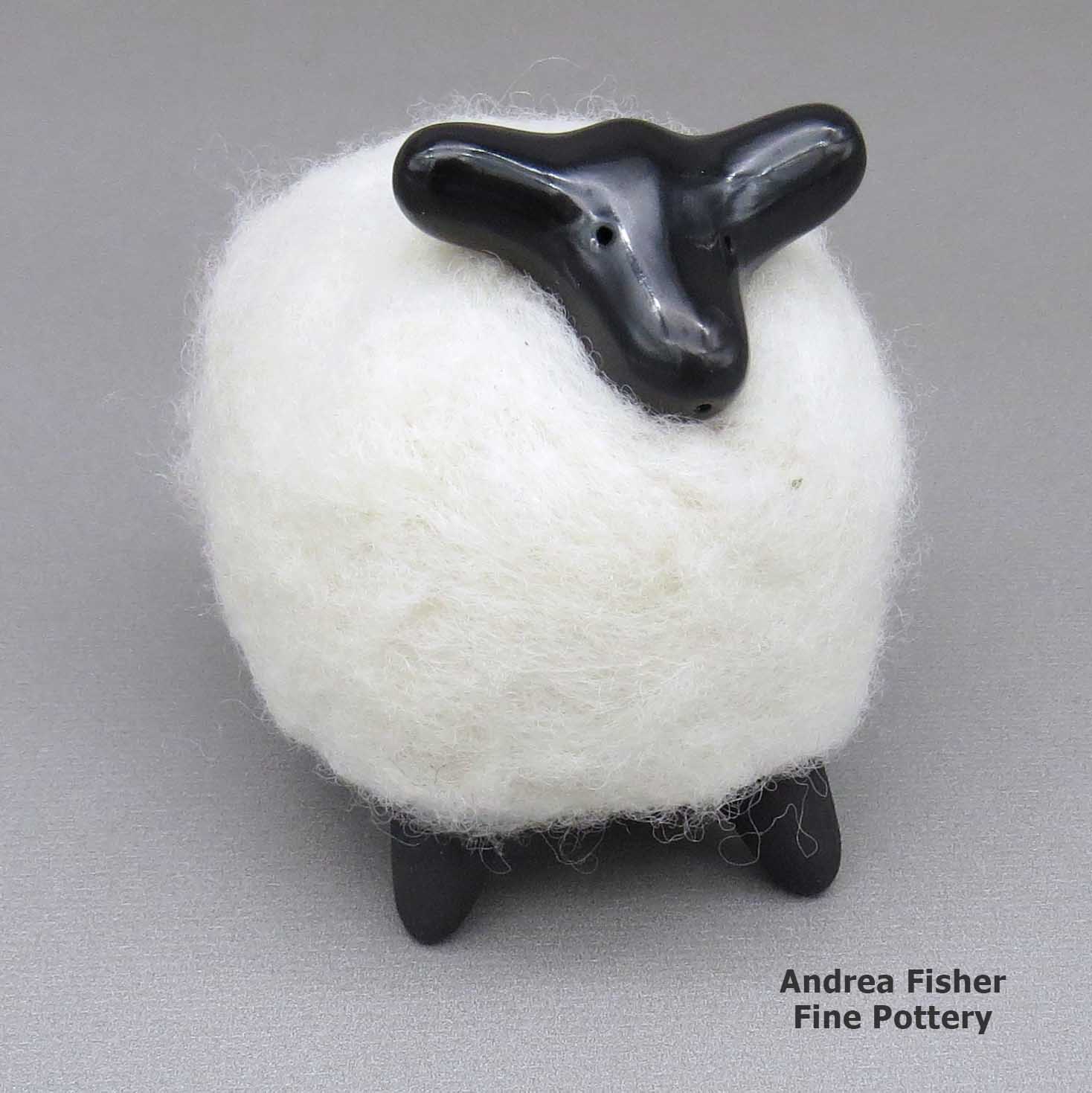

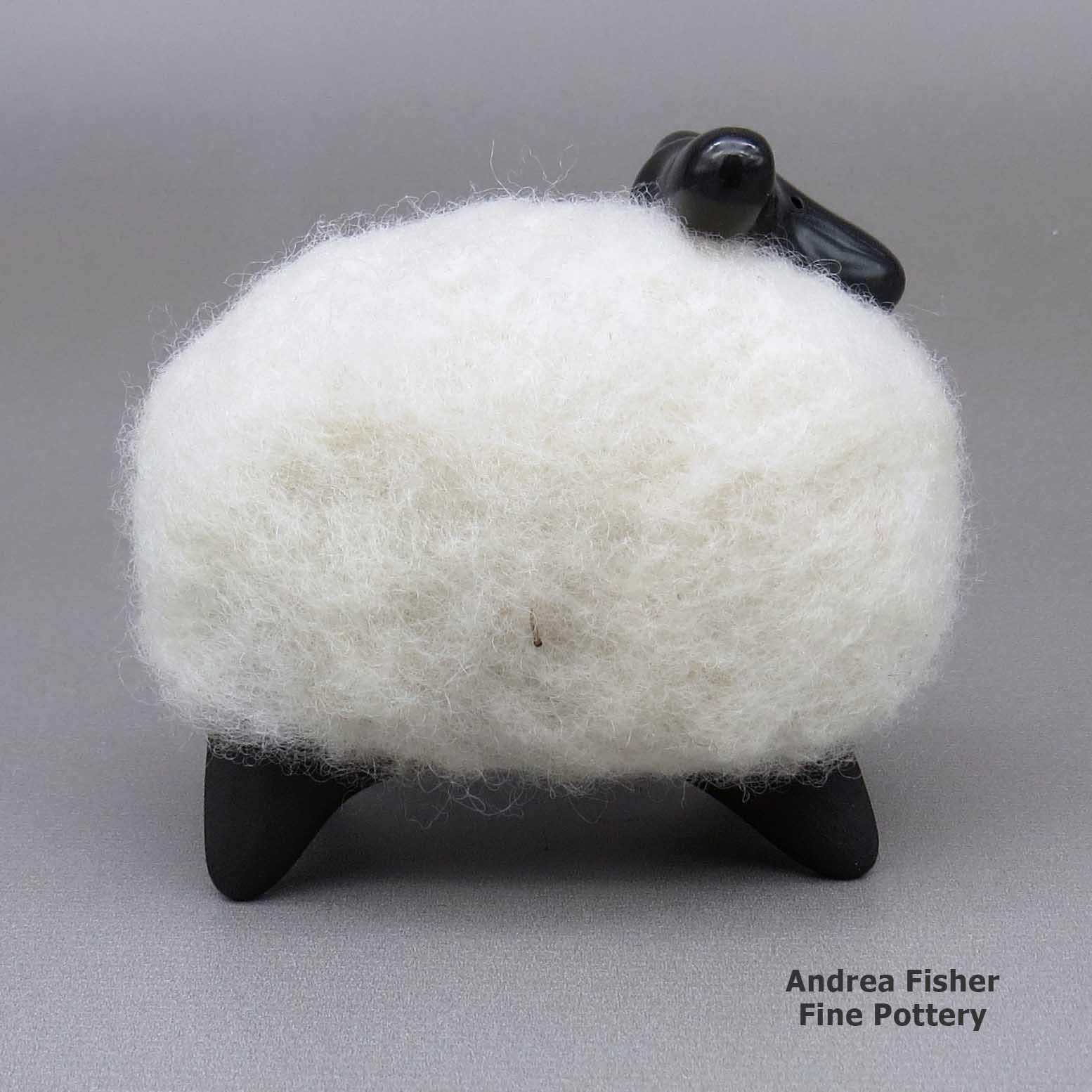

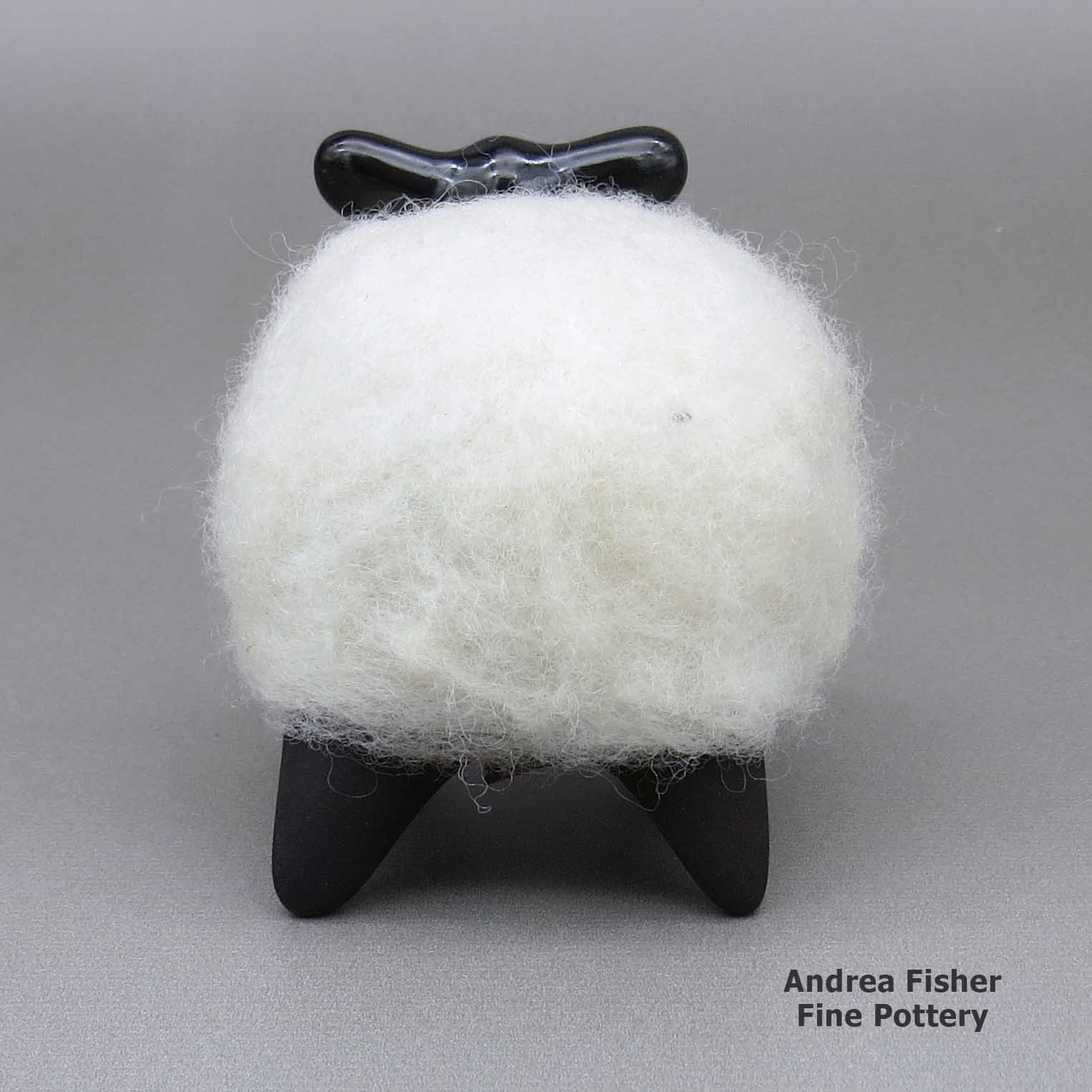

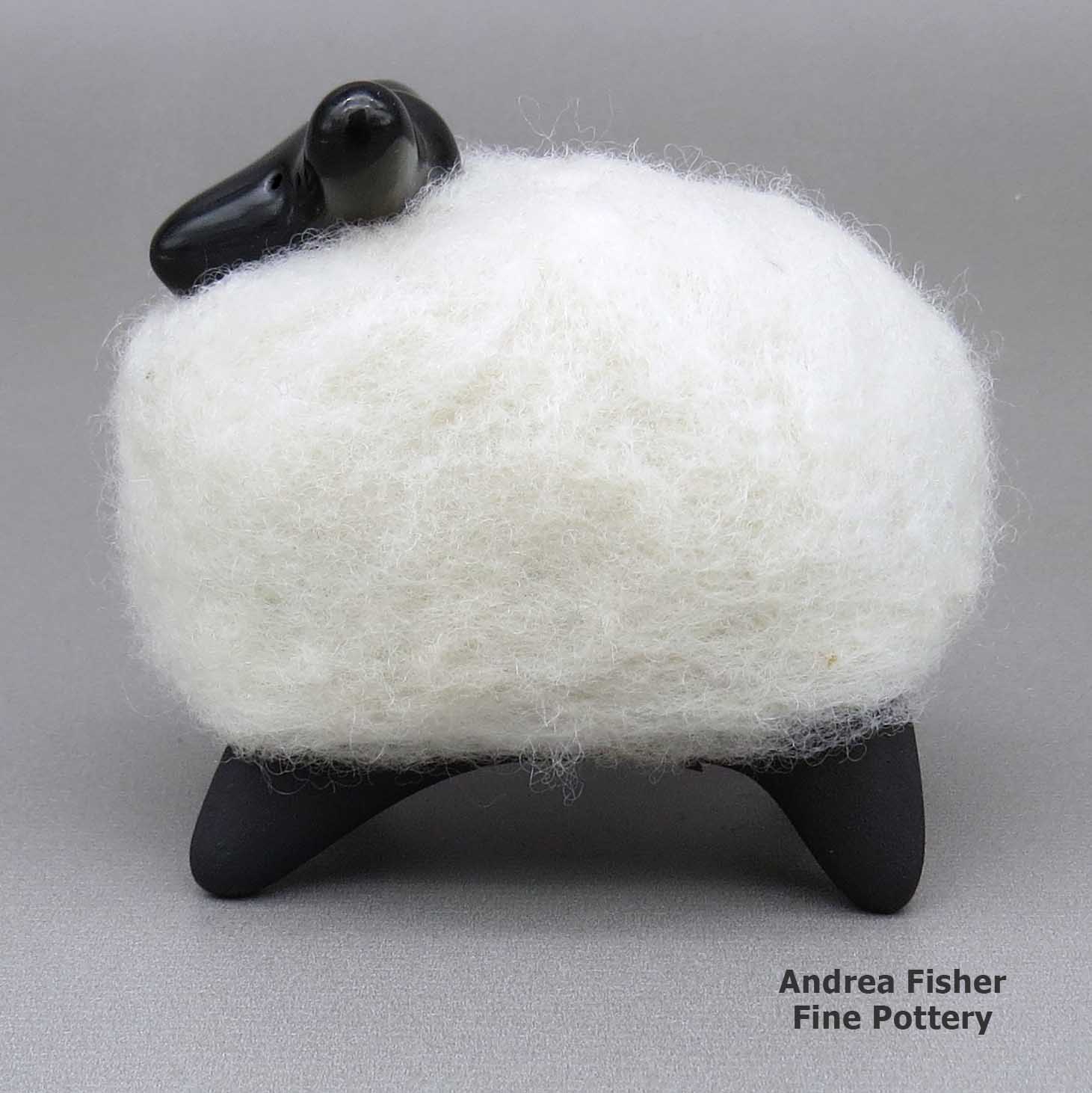

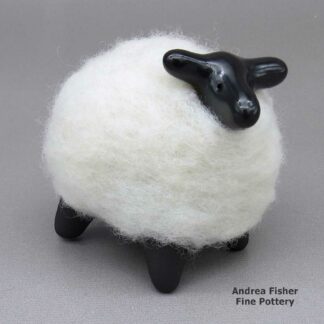

| Dimensions | 2.75 × 2.25 × 3 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2023 |

| Signature | Joe G and Eunice Naranjo SCP |

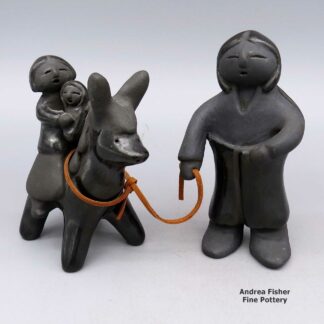

Joe and Eunice Naranjo, zzsc3a067m5, Black sheep figure with white wool body

$150.00

A polished black sheep figure with a white wool body

In stock

Brand

Naranjo, Joe and Eunice

After they were married, Eunice moved to Joe's home at Santa Clara Pueblo. She had learned to weave as she grew up but said she didn't have the patience needed for it. So Joe taught her how to make pottery. Together they started participating in the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show in the mid-1990s.

Joe generally makes the pieces, Eunice sands them, Joe carves them, polishes them and fires them. On some pieces Joe's cousin, Kevin Naranjo, adds some sgraffito designs.

Eunice makes pottery of her own, too. She generally makes black animal figures: cows and sheep, and decorates them with bits of wool and cowhide.

Some Awards earned by Joe and Eunice

- 2023 Santa Fe Indian market, Classification II-D, Category 806 - With added elements (like beads, feathers, stones, etc), any form, Second Place

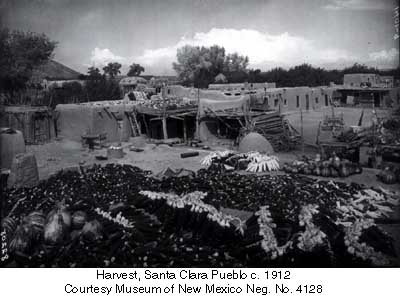

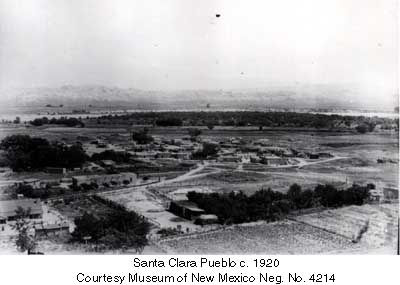

A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

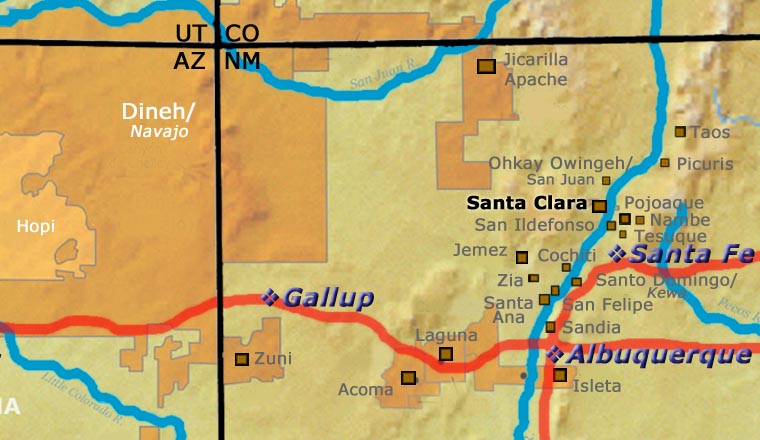

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

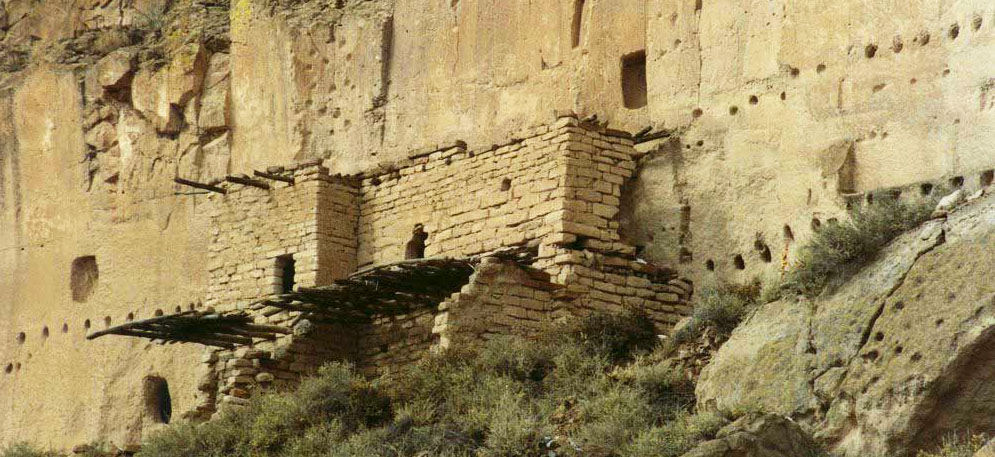

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Figures and Figurines

Generally, "Figure" denotes a real or mythic creature, like an owl or human or katsina or Corn Maiden. Whether form or decoration, all Puebloan pottery figures are meant to invoke particular spiritual essences. That's why "effigy" is used almost as often as "figure" to denote these pieces.

Among most Puebloans, the figure of an owl, for example, signifies all the physical and spiritual aspects attributed to the owl. It's a form of prayer to the spirit of "Owl" and the appropriately decorated physical form is meant to make that spirit manifest. However, to the Zuni people an owl is a good omen and to the Tewa people, an owl is a bad omen. Some potters at Santa Clara have made owls anyway, they just shaped and decorated them to reflect that "badness."

That explanation may make more sense in the case of the Corn Maiden as she is a mythic entity whose existence revolves around the most ubiquitous food staple in the Puebloan world: corn (maize). All representations of the Corn Maiden are meant to invoke her benevolence and abundance for their people. Because of her mythical/spiritual nature, different pueblos have slightly different physical forms for her but they all incorporate the basic form of a female human face on an ear of corn.

The potters of Tesuque turned out thousands of muna figures (also known as rain gods)for several decades, until they virutally burned out their pottery tradition. These muna had very specific shapes but were decorated with everything from micaceous slips to incised lines to polychrome geometric designs to poster paints. They were also made purely for domestic American consumption, sometimes delivered by the barrel to be used as prizes and giveaways.

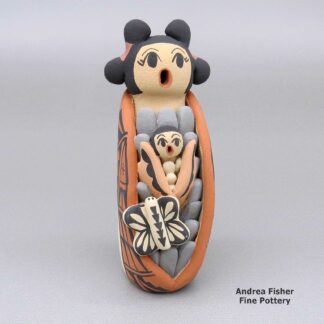

The Storyteller is another figure based on Puebloan tradition: a tribal elder singing the stories of the tribe's oral history to the children. The original was based on the traditional cultural story: a grandfather singing his part of the story in his native language so the children learn both the language and their identity against the backdrop of that history. Shortly, the storyteller form was duplicated in several other pueblos, each pueblo's potters adapting the form to their local situation. In some places, the grandmother became the primary sex of their storytellers. At Jemez, that responsibility was shared between grandmothers and grandfathers. Then some potters in search of new niches in the marketplace branched into making "spirit figure" storytellers, like eagles, ravens, hummingbirds, cats and dogs. Some Zuni potters have made storyteller owls.

Similar to the Storyteller is the Story Time: a set of separate children displayed around a larger central singing figure.

The Nativity set (also known as nacimiento) is a set of figures based on the intersection of Puebloan mythologies and stories they heard from Christian missionaries. Those potters who make them also tend to favor dress, shapes and designs that reflect their own heritage(s). The first few nativities made at Tesuque Pueblo were decorated with Spanish colonial costumes but that soon changed and every nativity made since has a distinct blend of Native American and Christian, with no other reference to colonialism. The "Singing Angel" (a single standing figure with outstretched wings and hands clasped together in prayer) and "Flight to Egypt" (usually depicting Mary with a baby Jesus on the back of a donkey and a standing Joseph nearby holding the rein) are similar mixes of tribal and Christian figures. The miniature nativities made by Santa Clara/Dineh artist Linda Askan clearly show Dineh religious influence in the headresses worn by Joseph, the angel and the three wise men. At the same time, the Dineh Folk Art nativities made by Jonathan Chee are based on the realities of daily Dineh life: the three wise men wear wide-brim hats and blue jeans, and bring gifts of salt and 50-pound bags of flour.

Pueblo and Dineh artists also make a full zoo of domesticated, farm and wild animal figures: horses, donkeys, cows, chickens, pigs, sheep, turkeys, giraffes, elephants, dogs, cats, mermaids, women-dressed-up-and-taking-selfies and cowboys among them.

Folk Art: Themes from Village Life

In most pottery-making families, children are encouraged to play with clay, making forms, scratching and painting designs, even putting their pieces in the fire. All kinds of shapes, forms, figures and creatures emerge from the flames. In some villages, those same children grow up to become figure-makers who portray aspects of the village life around them. Ubiquitous figures include chickens, coyotes, turtles, horses, bears, turkeys and fish.

In some pueblos, human likenesses on pottery are banned. In others, almost anything goes. In some, that dividing line is between indigenous religion and Christianity, while in others, those are somewhat merged.

The storyteller figure is a special figure from "village life." The way the ancient oral histories were passed down through the generations were through grandparents singing them to their grandchildren in the ancient tongues. It's hard to image a Hopi potter making storytellers but there are some Hopi potters who carve, etch and paint human (usually wearing katsina masks) on their pieces. Some of those designs are set against village backgrounds. There have been a couple Hopi potters who made figurines of katsinas (in that world, when one puts on the clothing and dons the mask, one becomes the katsina).

Only Christian Dineh potters picture forms other than yeibichai (or their costumed representatives) on their pieces. Elizabeth Manygoats has a whole series of Lifestyle pots inspired by scenes from the day-to-day life around her. She also makes human and animal figures. A favorite has been her figures of women dressed up and taking selfies... Her husband, Jonathan Chee, also makes Navajo Folk Art figures, except he incorporates a lot of motor vehicles in his work, too.

Among the Rio Grande pueblos, the potters of Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Jemez, Zia and Cochiti picture human forms in some of their designs. Generally, those humans are pictured participating in one or another ceremony on the pueblo and are dressed in the appropriate garments (and makeup) for the ceremony, except at Cochiti.

Cochiti has a long history of making figurative pottery and while that was paused during the long occupation by the Spanish, it has only expanded since the railroad first reached the pueblo. The storyteller figure was first innovated at Cochiti and potters there have since add multiple variations to that basic theme. They have also made deer, antelope, bear, horse and other storyteller figures, along with Corn Maidens, Singing Angels, mermaids, opera singers, koshares and two-headed circus ringmasters.

Similarly to Cochiti, Jemez potters make lots of various-creatured storytellers but they also paint, carve and etch images of various pueblo dancers in full costumes with masks. Some Jemez potters have become famous for their koshare figures.

Since the popularity of sgraffito designs exploded, there has been an equally great expansion in appropriately dressed eagle, deer, antelope, bear and other clan dancer designs.

Amelia Tafoya Family Tree - Santa Clara Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Amelia Tafoya & Avristo Naranjo

- Isabel Naranjo (1922-) & Jose Eugene Naranjo

- Elaine Naranjo Filbert (1944-) & James Filbert

- Colleen F. Filbert

- Imogene Hale

- JoeAnn D. Naranjo (1952-)

- Arlo White

- Clarissa White

- Lenna White

- Joseph G. Naranjo & Eunice Maize Naranjo (Dineh)

- Maria (1942-) and Andy Padilla

- Elaine Naranjo Filbert (1944-) & James Filbert

- Maria I. Naranjo (1919-)

- Martha Mirabal (1946-)

- James Mirabal

- Tammie Mirabal

- Martha Mirabal (1946-)