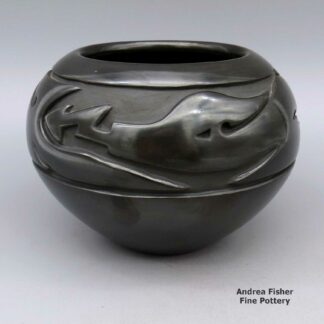

| Dimensions | 4.75 × 4.75 × 5.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has adhesive residue on bottom |

| Date Born | 1989 |

| Signature | Juan Tafoya San Ildefonso Pueblo, with hallmark |

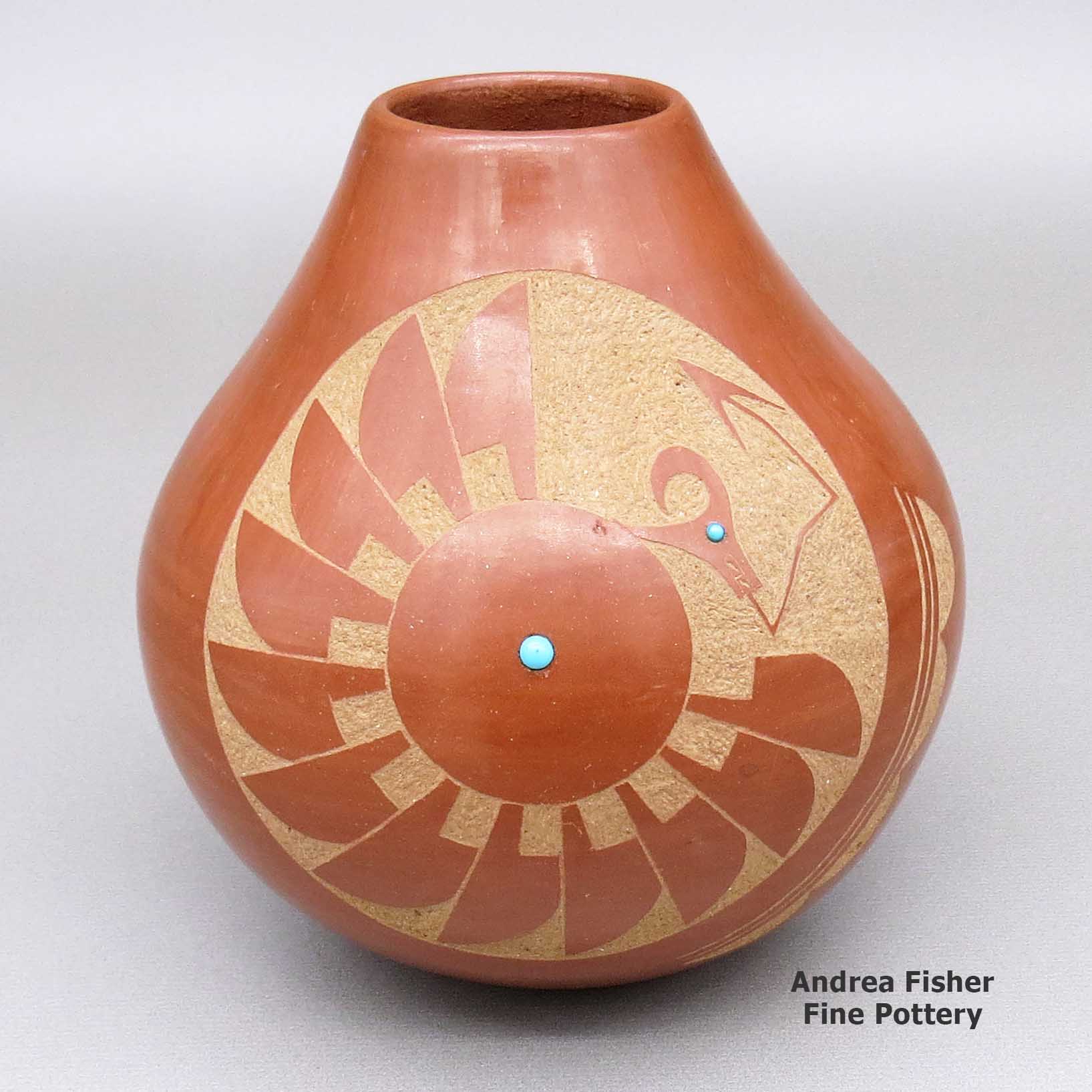

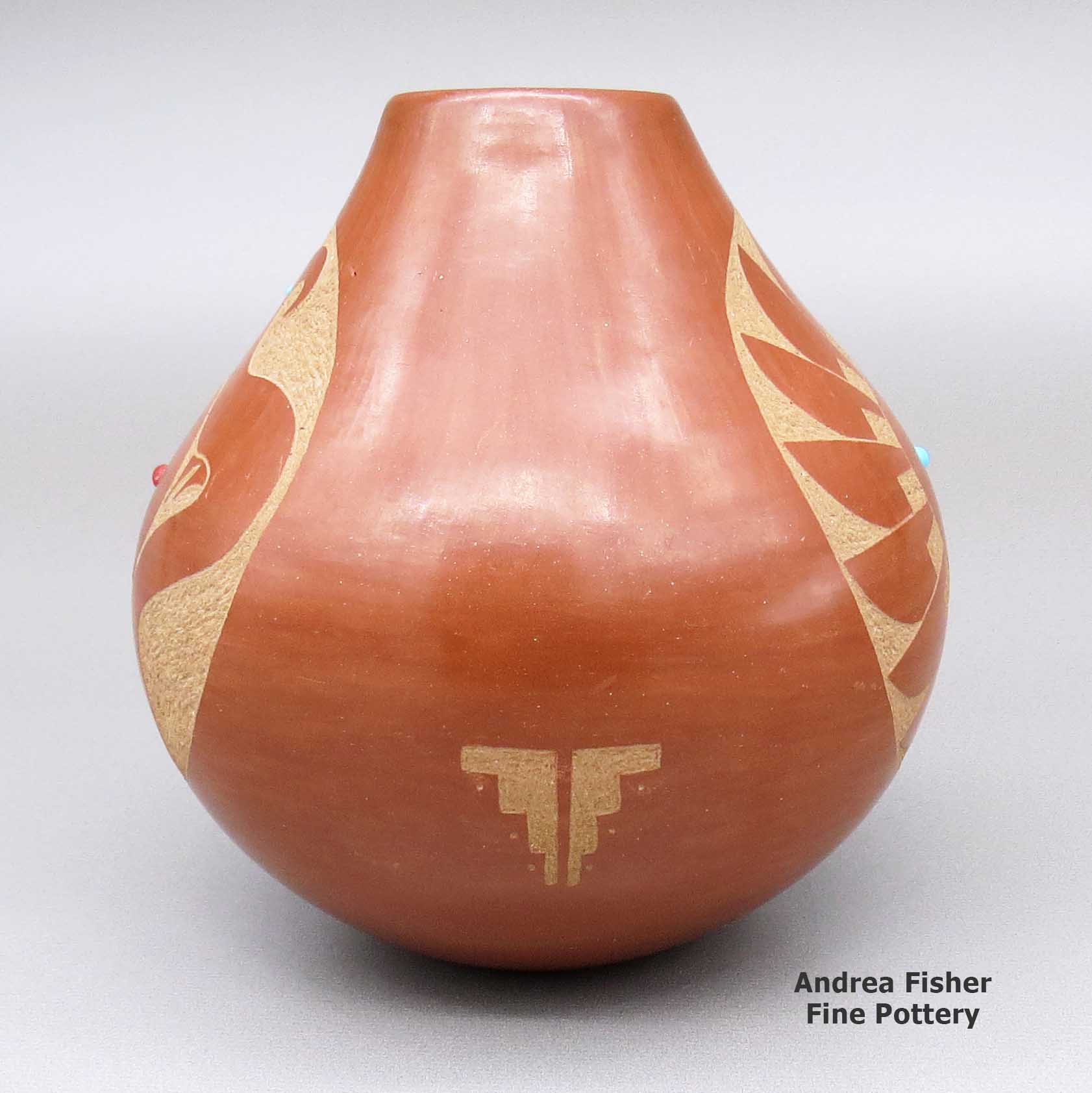

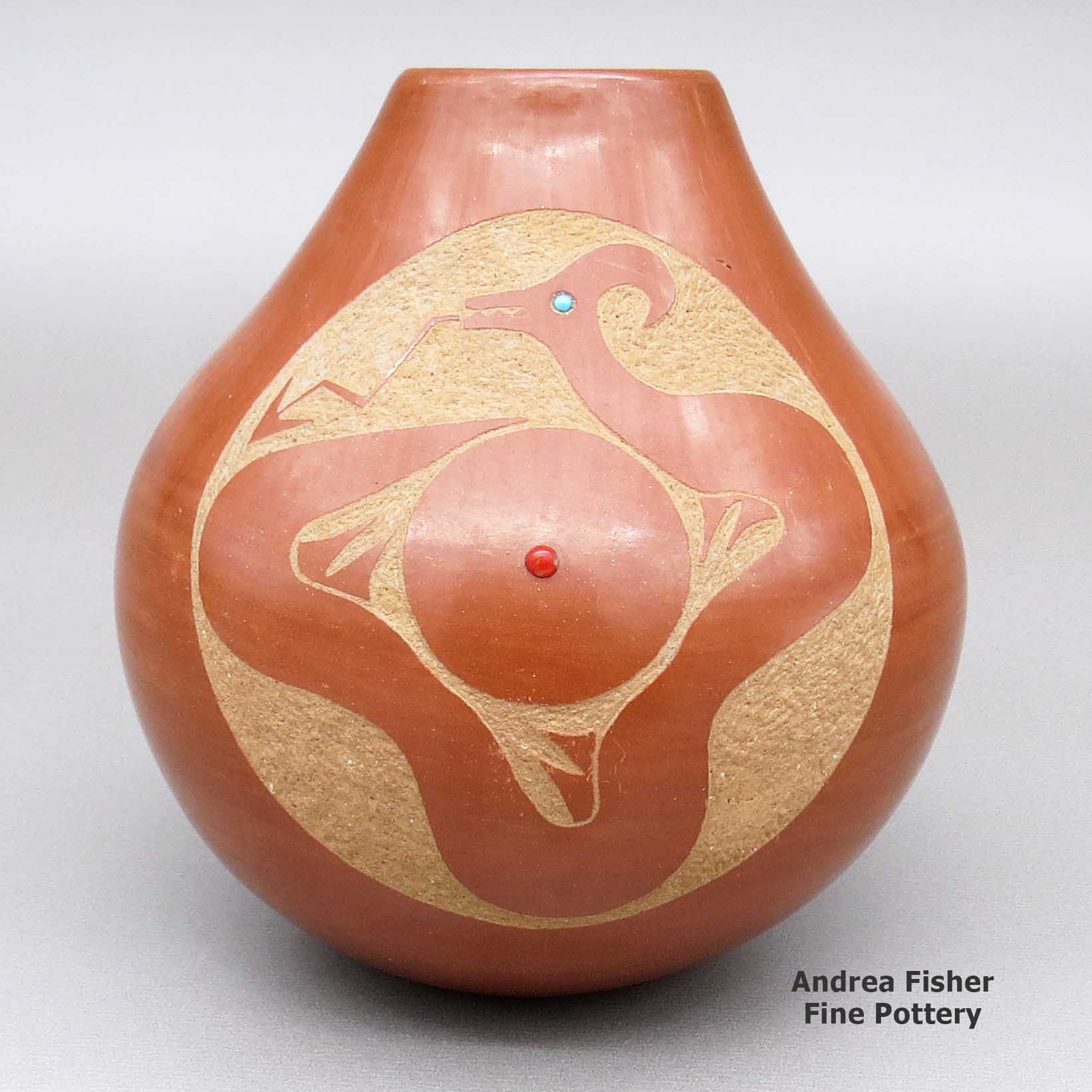

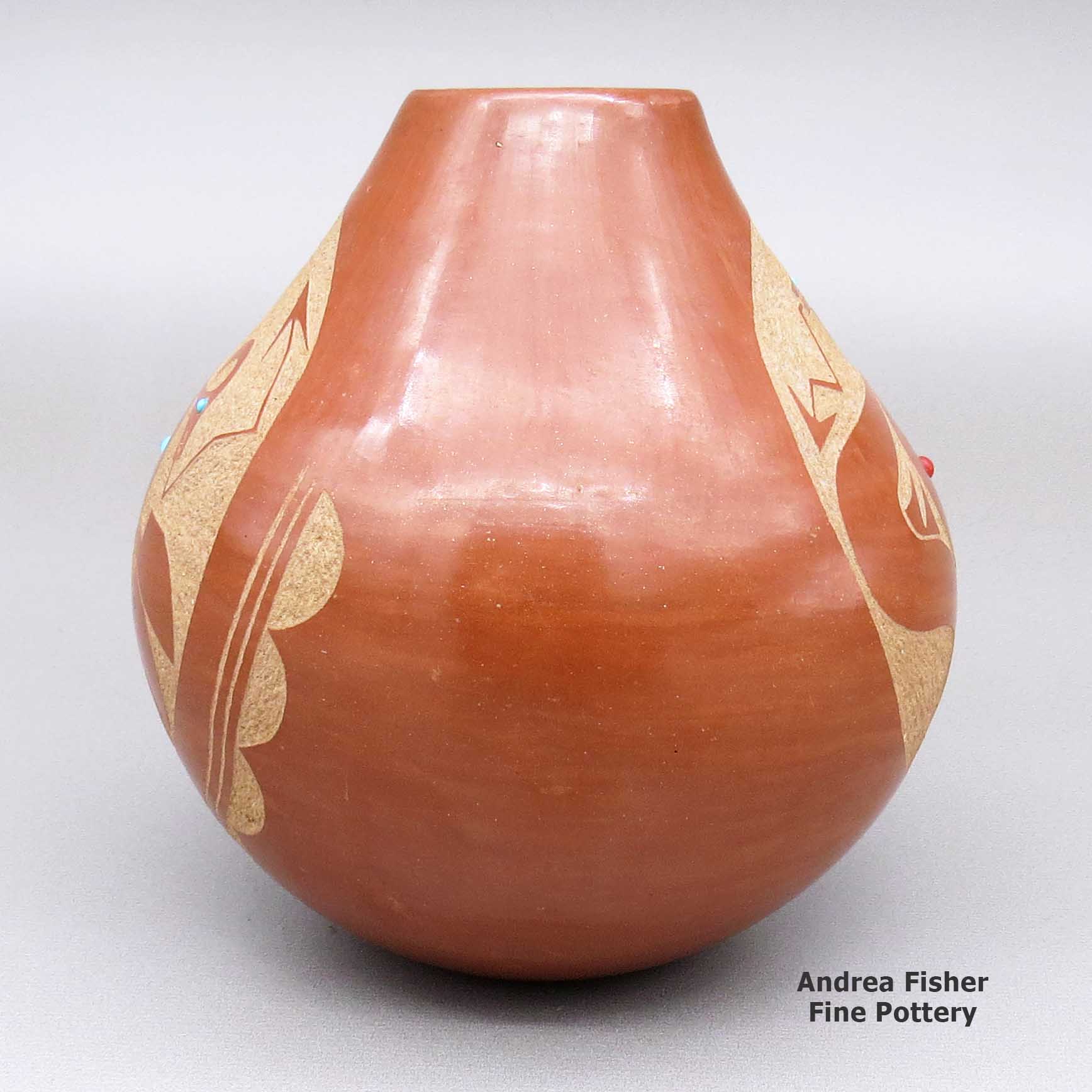

Juan Tafoya, cjsi3c230, Red jar with sgraffito design and inlays

$650.00

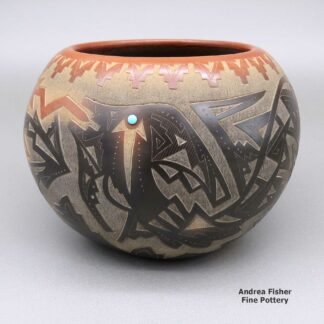

A red jar with a sgraffito avanyu, feather ring, and geometric design, plus inlaid turquoise and stone details

In stock

Brand

Tafoya, Juan

Juan Tafoya (1949-2006) was a potter from San Ildefonso Pueblo. His mother was Donicia Tafoya, among his siblings were Annette Romero and Elizabeth Lovato.

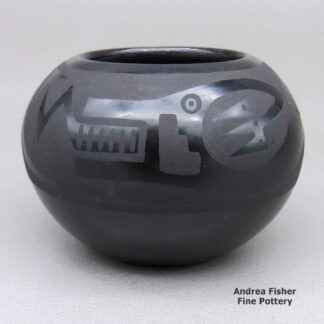

Juan liked to make blackware jars and bowls. Sometimes he'd add sgraffito designs, sometimes he'd add inlaid strands of turquoise beads. Sometimes he made miniatures. Juan was one of the first to experiment with making two-tone pottery. His style was very similar to that of Popovi Da, Tony Da and Dora Tse Pe.

Juan was a participant in the Santa Fe Indian Market for about 30 years, beginning in 1972. He earned a few First and Second Place ribbons for miniatures and incised black jars. He also participated in events like the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show, the New Mexico State Fair, the New Mexico Arts & Crafts Show and at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institute.

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

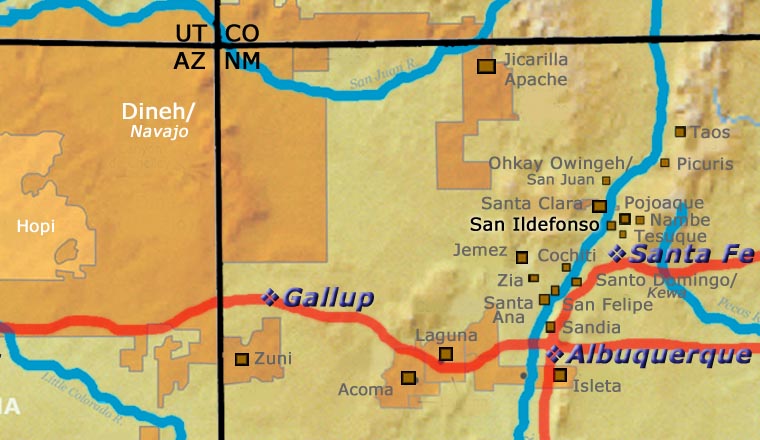

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

Tewa Design Sources

The Northern Tewa people are mostly from the villages of Ohkay Owingeh, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Nambé and Tesuque. The Hopi-Tewa of Arizona are descendants of the Southern Tewa. The Tewa share a common heritage from back in the 1200s CE, when their ancestors lived in the canyons and valleys west of Mesa Verde. When the Great Drought hit (around 1276 CE), they were already on the move because of other recent bad weather events. The kachina cult was developing around the same time and however it worked out, never took hold among the Tewa. The Tewas did incorporate the Medicine and Sacred Clown societies into their religious activities. Archaeologists have traced their tracks east from the Four Corners to the South San Juan Mountains, where they turned south and first built homes in New Mexico around Ojo Caliente. From there, they spread further south into the valley of the Rio Chama and then spread out there for a hundred years.

As more and more Dineh and Apaches came into the area in the 1400s, the Tewa moved downstream along the Chama. Some of them moved up onto the Pajarito Plateau while others sorted out into small villages on the east side of the Rio Grande. Shortly some of them came to the southern edge of the Santa Fe River Basin and found the Galisteo Creek Basin on the other side populated by Eastern Keres people. It was the same when they came to the mouth of the Santa Fe River at the Rio Grande: further south along the river was populated by other Eastern Keres people. And just upstream across the Rio Grande was the outlet of Frijoles Canyon, home of many Eastern Keres people in the 1400s and 1500s.

There were indigenous Tanoan people already living throughout the Rio Grande area and the two groups merged reasonably well. Somewhere in this time period, sodalities came into being: the Summer People and the Winter People. Some archaeologists believe the incoming Tewa became the Summer People and the Tanoans became the Winter People, based on the fact the incoming Tewas brought new seeds, new agricultural and ceramic technology, new dances and new religion. When the Spanish first arrived in the area around 1540 CE, the Tewa Basin was well occupied by the merged Tewa/Tano people. Those Tanoans who preferred not to merge built separate pueblos for themselves in more marginal areas in the Santa Fe and Galisteo River basins. Depopulation began after the Spanish left and didn't take their various diseases with them. It was after Don Diego de Vargas arrived in 1598 that the survivors were separated into their separate villages and restricted to those.

The Northern Tewa

The Northern Tewa design pallette contains a number of motifs common to many puebloan societies: hummingbirds, turtles, tadpoles, quails, owls, deer, hands, hoof prints, bird tracks and more. It's easy to see how many evolved from designs from the Flower World Complex of central Mexico. The Santa Clara and Nambé avanyu is a winding serpent with usually, one or three feathers on the top of its head. The San Ildefonso avanyu usually has a three- or five-pronged plume on its head. The avanyu itself is evolved from images of Quetzalcoatl. While the avanyu is the protective spirit of water and springs it also represents what happens when there's a heavy rain in the desert: flash floods that can wipe out whole villages.

Most San Ildefonso potters paint their decorations, only a few work with sgraffito decorations and a few work with inlaid stones and heishi beads. At Santa Clara, potters carve, scratch and paint their pieces, then sometimes reheat them with a blowtorch and mount stones on them... almost anything goes. The design palette is traditional to trend-setting contemporary, although the subject matter is usually the avanyu, or hummingbirds, turtles, quails, fish, deer, bear paws and bear claws, etc.

Because they had easy access to micaceous clay, the people of Nambé and Ohkay Owingeh built a brisk business in making micaceous pots and cookware, similarly to the people of Taos and Picuris at the time. More recently, Lonnie Vigil and Robert Vigil have produced micaceous pottery at Nambé while Clarence Cruz has been producing micaceous cookware and utensils at Ohkay Owingeh.

The people of Ohkay Owingeh decided to start over after essentially losing their pottery tradition in the 1800s. They never stopped making utilitarian pottery but even that declined in the late 1800s. In the 1920s, when it was decided they would work to revive a purely Ohkay Owingeh tradition, they settled on the designs found on some prehistoric pottery that had been found while digging in an old Tewa pueblo on Ohkay Owingeh land. The pottery was dated to the few decades before the Spanish arrived, hence: pre-contact and innocent of European influence. Their definition of Potsuwi'i pottery is very specific as to the colors and textures of the clay used and the designs carved, scratched or painted on them. Many of the design patterns are reflective of rock art from a thousand years ago.

The Southern Tewa

The Santa Fe Basin is where the Southern Tewa settled. They seem to have followed the idea that "further south is a better life," and they kept going south until they came up against other relatively entrenched people (migrants spreading out from Santo Domingo into the Galisteo Creek Basin). The Santa Fe Basin showed signs of having been occupied by the Tanoan people off-and-on over the centuries. It was a marginal landscape for farming but it was up against the Cerrillos Hills where they found turquoise, silver and lead ore. The turquoise trade was very profitable for some but the lead ore made possible different design techniques to use on fired pottery. The potters of the village did well producing lead-glazed pottery (not sealed, glazed only where the lead paint was applied and then ran in the heat of the fire).

In 1692, when the Spanish arrived in full force to reconquer northern New Mexico, most of the Tewa people in Tewa Basin gathered atop Black Mesa, a volcanic plug that sits between Santa Clara and San Ildefonso Pueblos. They stayed up there for months, almost impervious to Spanish attack. Eventually, though, they made a deal with the Spanish and returned to their various pueblos.

Shortly after that, the Spanish issued an order limiting access to the lead mines at the Cerrillos Hills to Spanish citizens only and, with that, the Southern Tewa lost their last possibility for remaining in a parched landscape. Because of the boundaries imposed by the Spanish, they all ran north in the night to the area of Chimayo. That didn't work out quickly, so they moved to the area of Santa Clara, again during the night. That didn't work out either as they were challenged by a Spanish priest and they killed him. From there they moved quickly to the area of Zuni, then up to First Mesa where they made a deal with the people of Walpi and were shortly living in their own village near the base of First Mesa. Over the centuries they came to be known as the Hopi-Tewa. In that same time period many of the religious aspects of Hopi society have made their way into Hopi-Tewa society. The Hopi-Tewa design pallette consists mostly of designs revived from potsherds found around the ancient pueblos of Awatovi, Sikyátki, Payupki and Kawaika'a, all of which are in the vicinity of the Hopi mesas.

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About the Avanyu

The avanyu is a mythical water creature likened to the feathered and plumed serpents of Mesoamerica. The design is primarily part of the design palette of Tewa potters from the Tewa Basin, and even there it varies by pueblo and artist. Wherever the artist is, the avanyu design generally represents the spirit of water rushing through a village after a downpour. The avanyu is also seen as the Keeper of Springs and Guardian of Water. The image is a prayer for rain with the realization of what a downpour can do when it falls on the hard soil of the arid and semi-arid Southwestern deserts.

Artists from San Ildefonso Pueblo generally use an avanyu design with a three-plumed head while Santa Clara Pueblo potters generally use an avanyu with three feathers hanging off the head. The avanyu always has a forked tongue, signifying the lightning bolts that herald its arrival. Some have simplified the design to one feather or plume while others have stylized the design and almost made it cubic or Oriental in design and layout.

Hopi-Tewa potters generally use a somewhat similar Hopi version of a flying, feathered serpent named kwataka. The Zuni version is Kolowisi, although it has been determined that the power of Kolowisi is too much for anyone who is not of Zuni descent so depictions of it have gotten almost as rare as depictions of kwataka.