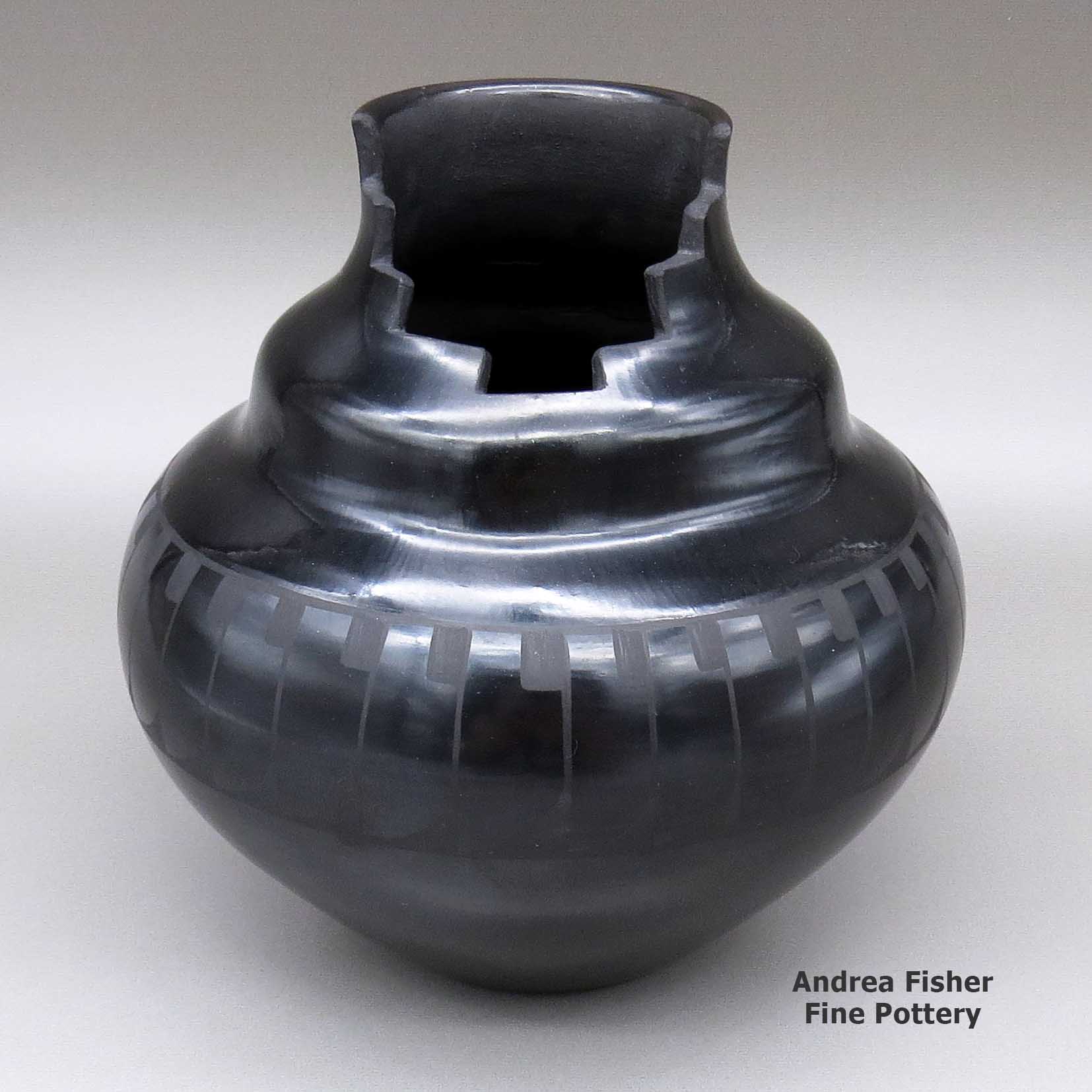

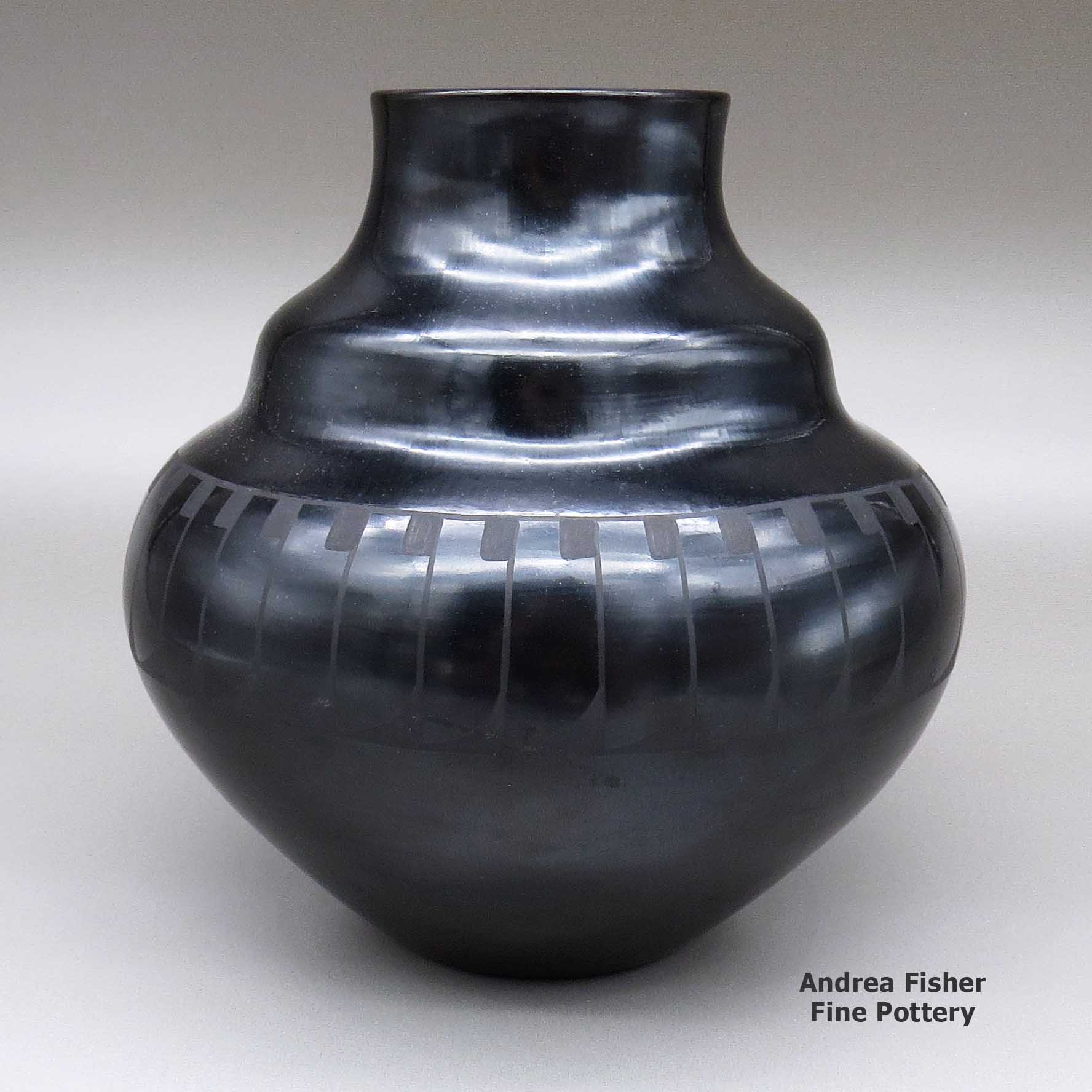

| Dimensions | 8.25 × 8.25 × 9.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, rubbing on bottom |

| Date Born | 1982 |

| Signature | Juan Tafoya San Ildefonso Pueblo |

Juan Tafoya, zzsi3b548, Black-on-black double shouldered jar

$1,500.00

A black-on-black double shouldered jar decorated with a kiva step cut opening and a painted ring-of-feathers geometric design

In stock

Brand

Tafoya, Juan

Juan Tafoya (1949-2006) was a potter from San Ildefonso Pueblo. His mother was Donicia Tafoya, among his siblings were Annette Romero and Elizabeth Lovato.

Juan liked to make blackware jars and bowls. Sometimes he'd add sgraffito designs, sometimes he'd add inlaid strands of turquoise beads. Sometimes he made miniatures. Juan was one of the first to experiment with making two-tone pottery. His style was very similar to that of Popovi Da, Tony Da and Dora Tse Pe.

Juan was a participant in the Santa Fe Indian Market for about 30 years, beginning in 1972. He earned a few First and Second Place ribbons for miniatures and incised black jars. He also participated in events like the Eight Northern Pueblos Arts & Crafts Show, the New Mexico State Fair, the New Mexico Arts & Crafts Show and at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian Institute.

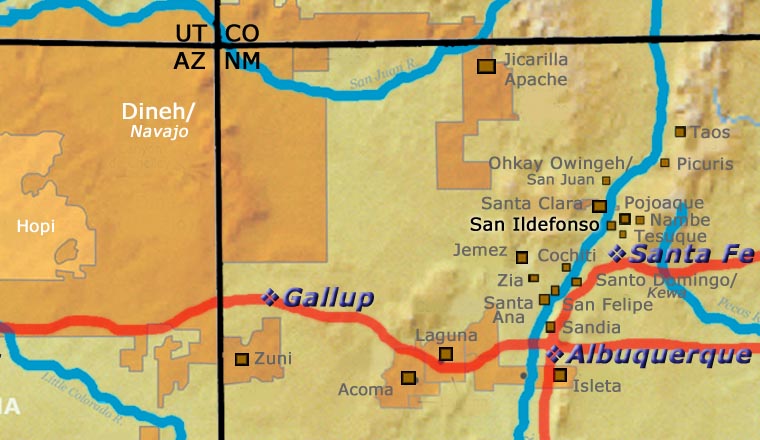

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

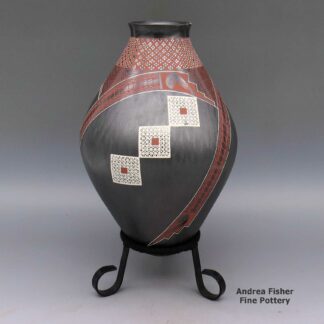

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.