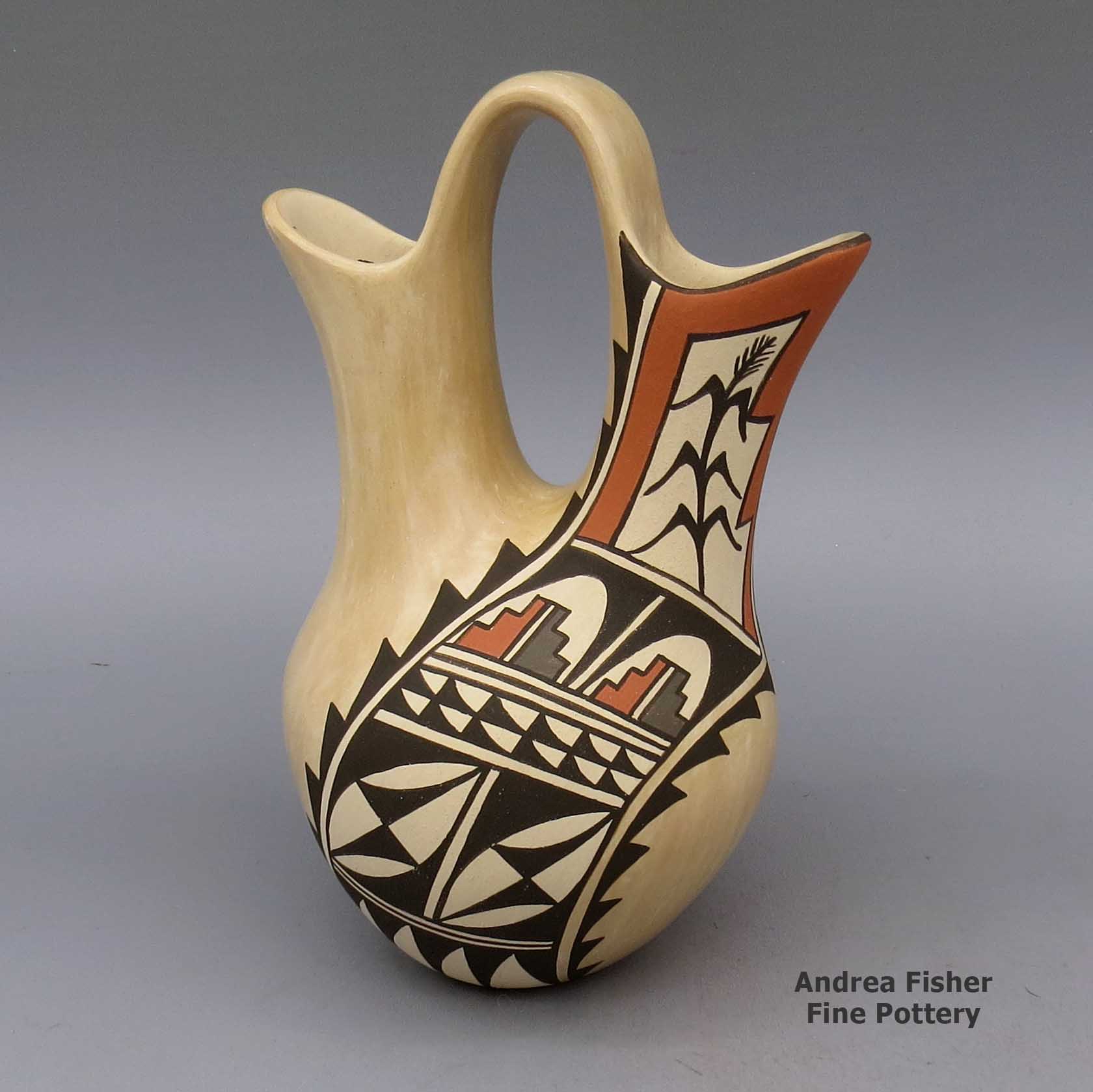

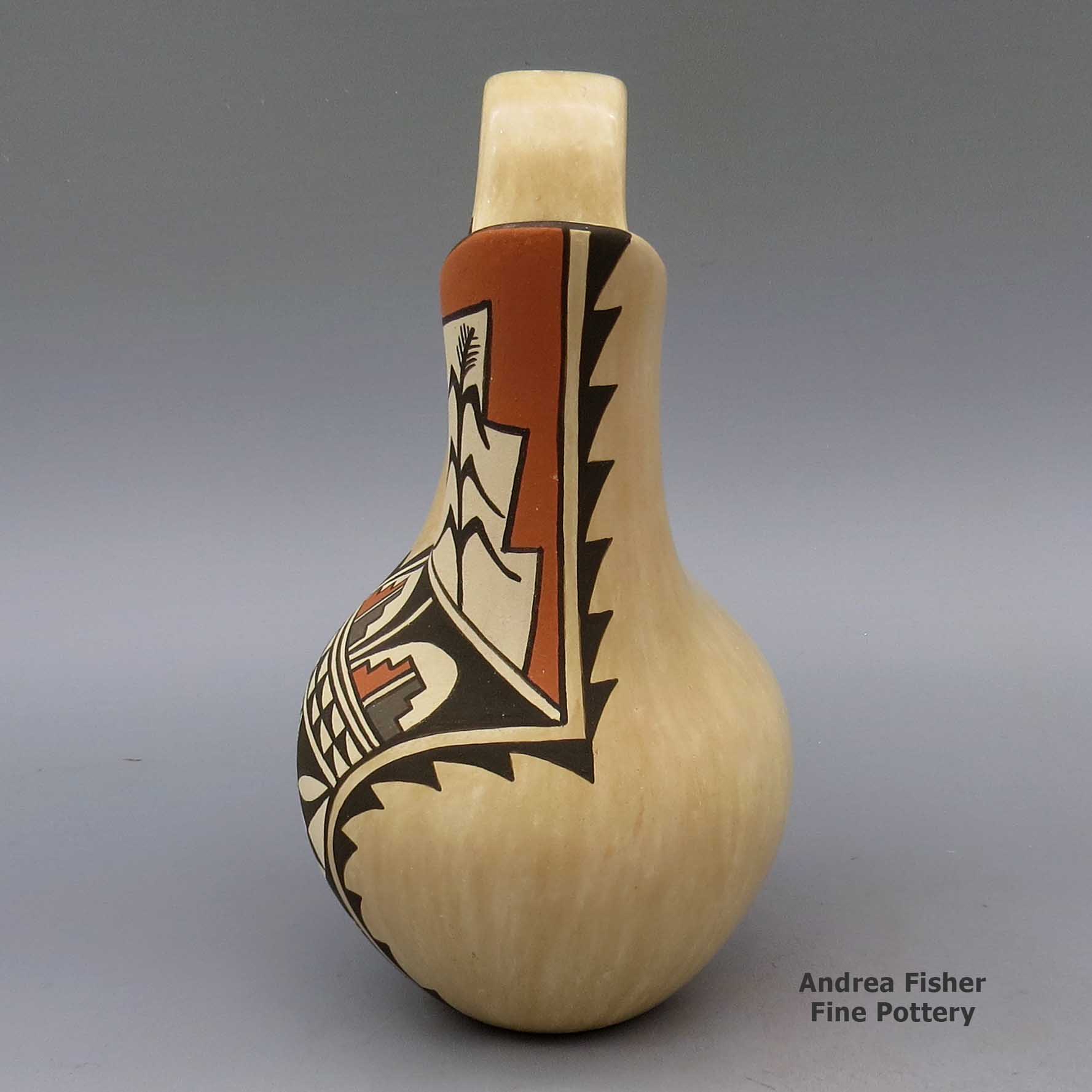

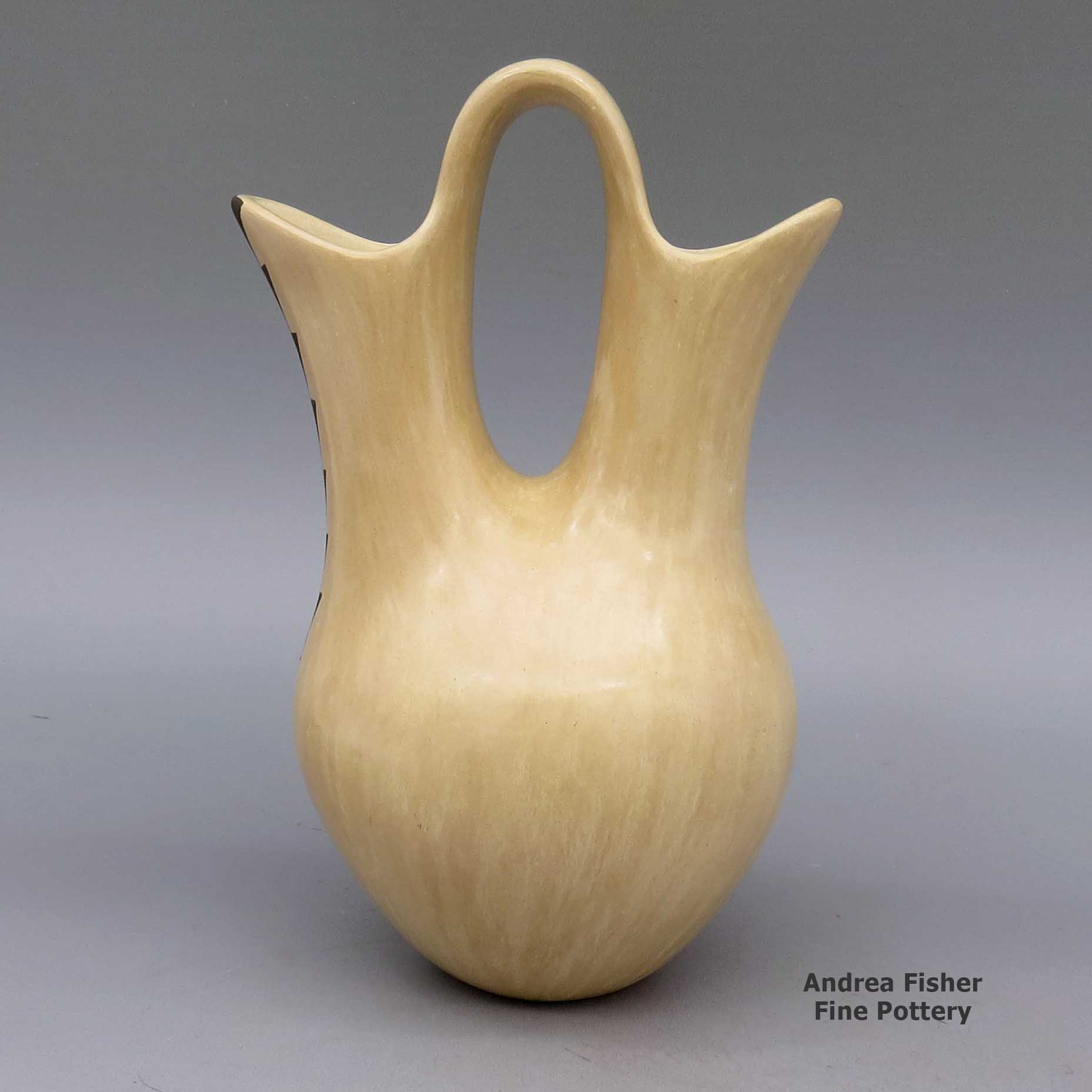

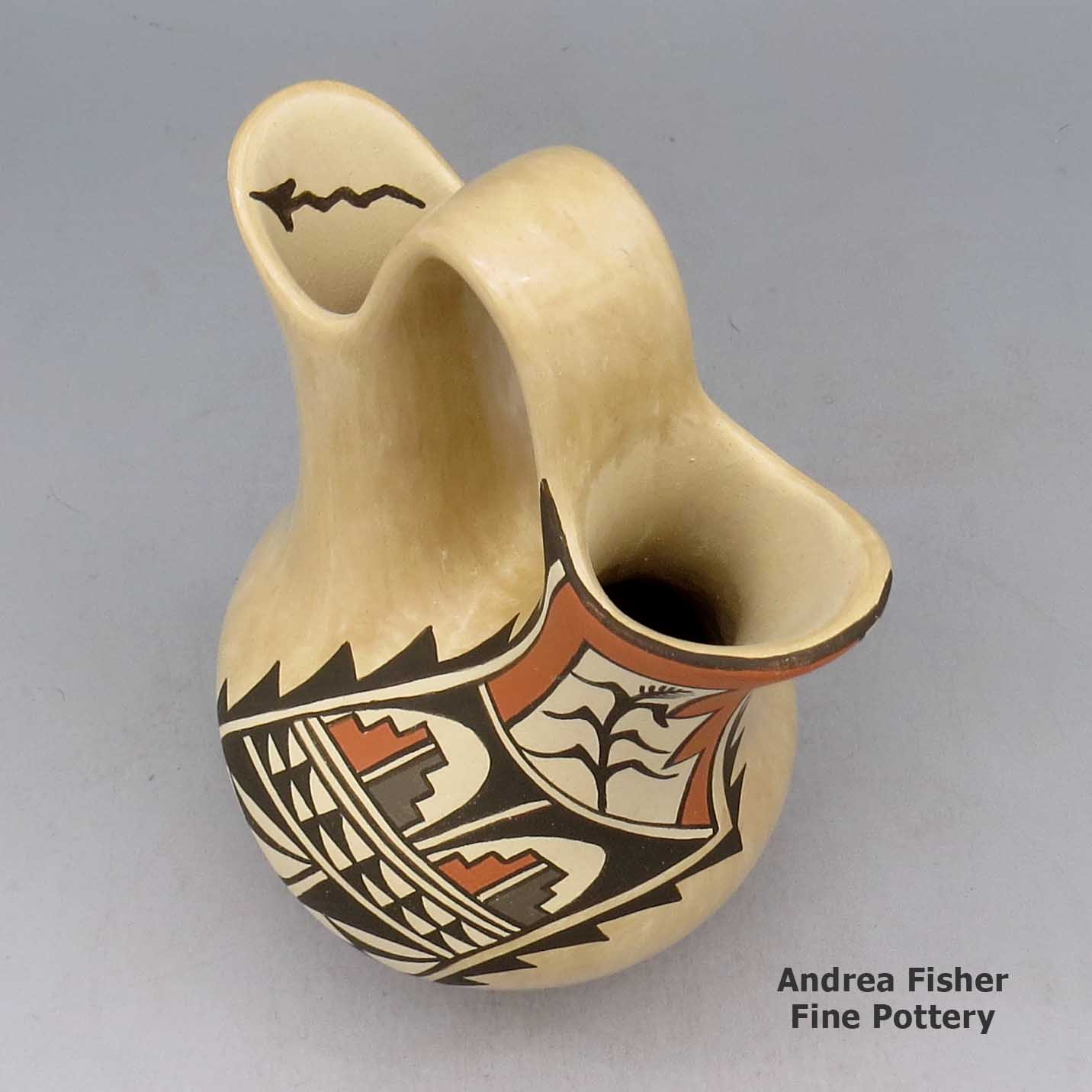

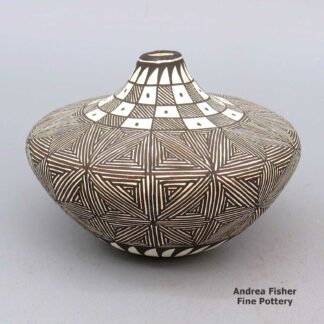

| Dimensions | 3.75 × 4.5 × 7.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | JCF Juanita Fragua Jemez Pue N.M |

Juanita Fragua, lkje2l324, Polychrome wedding vase with geometric design

$395.00

A polychrome wedding vase decorated with a corn plant and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Fragua, Juanita

Juanita Fragua was born into Jemez Pueblo in March 1935. Her mother was Rita Casiquito Magdalena, a woman from Zia Pueblo. Rita was an experienced Zia potter and, after making adjustments for Jemez clay, taught others at Jemez Pueblo how to make pottery. Later in life Juanita recognized Benina Shije, a sister Corn clan member from Zia, as also being important in the revival of pottery making at Jemez. The pottery tradition at Jemez Pueblo had been virtually extinct for 200 years.

Juanita studied some of the ancient Jemez pottery in the museums of Santa Fe and Albuquerque. She felt their lines were very simple, so she developed more complex designs of her own. She said they were inspired by elements of her Corn clan heritage but she also said, "It's all up here in my head."

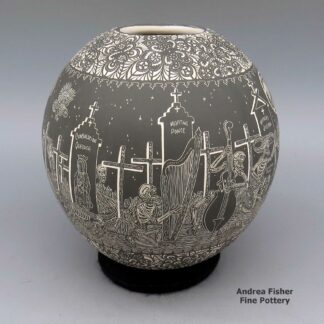

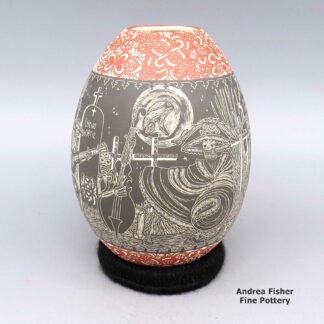

Juanita makes traditional polished tanware and redware, jars, bowls, cornmeal bowls, vases and wedding vases. Some she decorates with sgraffito work, some she lightly carves, most she paints with traditional designs. Juanita also does embroidery.

Juanita didn't limit herself to traditional Jemez practices either. She studied with Kiowa painter Al Momaday for a while, learning to draw and how to mix paints. Embroiderer Lorencita Bird shared designs and design techniques with her.

Juanita was part of the 1950s wave of pottery revivals passing through the pueblos. She felt free to try everything from sgraffito to carving to micaceous clay. The primary determinant of Jemez style is basically the colors of the base clay, the slips and the paints.

Juanita was a consummate artist and passed her knowledge and perspectives on to her children and many others. Her son, Clifford Fragua, is an internationally known sculptor. Her daughters, Glendora (Daubs) Fragua and Betty Jean Fragua, became award-earning potters.

In 2020, Juanita and Glendora collaborated on a piece they submitted to the Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market in Phoenix. It earned the First Place ribbon for Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Any design or form with native materials, kiln-fired pottery. Awarded for the collaborative artwork: "Generations." Juanita's ribbons have dates on them stretching back to the 1980 Santa Fe Indian Market.

Sadly, Juanita passed on just before Christmas, 2023.

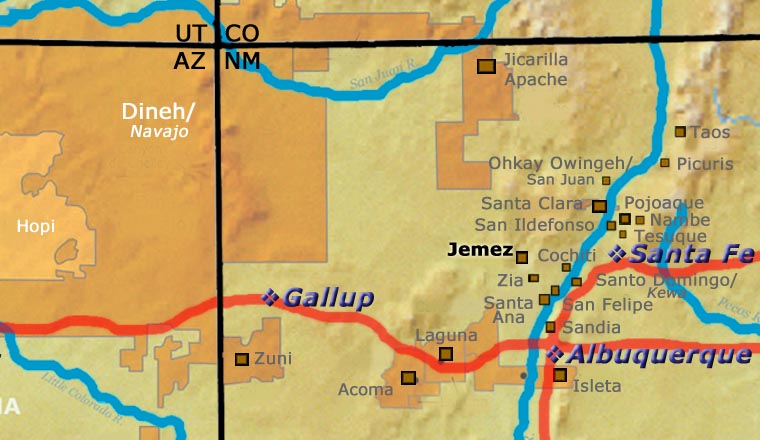

A Short History of Jemez Pueblo

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward, across the Upper San Juan River into the Gallina Highlands, then over the hill to the Canyon de San Diego area in the southern Jemez mountains. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa. The large migrations out of the Four Corners area began around 1250 and the area was almost entirely depopulated by 1300. The Towa-speakers who went southeast were pretty much settled by about 1350.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that pot sherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed by other Hopis around 1625). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, agriculture was hard. The Jemez had always been travelers and traders. Their people had traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico for generations. In those days they also made a lot of pottery and trading pottery with Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos for food was a brisk business.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and helped evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains.

It was around that time that the Hopi themselves destroyed Awatovi, the largest pueblo in the Hopi area (many of the people of Awatovi also spoke Towa). A Spanish missionary with a few soldiers had appeared at Awatovi in 1696 and forced the rebuilding of the mission. He also started getting people into the church. The leader of Awatovi went to the other Hopi pueblos and told their leaders that his people had strayed too far: they must be destroyed to cleanse the Earth of their sins. In the winter of 1700-1701, men from Walpi, Oraibi and a couple other pueblos invaded Awatovi while the men were in their kivas. The invaders pulled the ladders out of the kivas, poured baskets of hot red chile peppers and burning pine pitch down, then killed almost everyone. When the frenzy was over they burned the pueblo down and salted the earth around it so it would never be reoccupied.

On their return to the Jemez Mountains around 1700, the Jemez people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities. Even today, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Dineh territory at Jeddito.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Pecos Pueblo (more properly known as Cicuyé) are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé were the easternmost speakers of the Towa language in the Southwest. After the Pueblo Revolt, the Pecos area fell on increasingly hard times (constant Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, increasing drought). The pueblo was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents relocated to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Pecos tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Pecos families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

The Wedding Vase

- as told by Teresita Naranjo of Santa Clara Pueblo

The Wedding Vase has been used for a long, long time in Native American wedding ceremonies.

After a period of courtship, when a boy and girl decide to get married, they cannot do so until certain customs have been observed. The boy must first call all his relatives together to tell them that he desires to be married to a certain girl. If the relatives agree, two or three of the oldest men are chosen to call on the parents of the girl. They pray according to Indian custom and the oldest man will tell the parents of the girl what their purpose is in visiting. The girl’s parents never give a definite answer at this time, but just say that they will let the boy’s family know their decision later.

About a week later, the girl calls a meeting of her relatives. The family then decides what answer should be given. If the answer is “no” that is the end of it. If the answer is “yes” then the oldest men in her family are delegated to go to the boy’s home, and to give the answer, and to tell the boy on what day he can come to receive his bride-to-be. The boy must also notify all of his relatives on what day the girl will receive him, so that they will be able to have gifts for the girl.

Now the boy must find a Godmother and Godfather. The Godmother immediately starts making the wedding vase so that it will be finished by the time the girl is to be received. The Godmother also takes some of the stones which have been designated as holy and dips them into water, to make it holy water. It is with this holy water that the vase is filled on the day of the reception.

The reception day finally comes and the Godmother and Godfather lead the procession of the boy’s relatives to the home of the girl. The groom is the last in line and must stand at the door of the bride’s home until the gifts his relatives have brought have been opened and received by the bride.

The bride and groom now kneel in the middle of the room with the groom’s relatives and the bride’s parents praying all around them. The bride then gives her squash blossom necklace to the groom’s oldest male relative, while the groom gives his necklace to the bride’s oldest male relative. After each man has prayed, the groom’s necklace is placed on the bride, and the bride’s is likewise placed on the groom.

After the exchange of squash blossom necklaces and prayers, the Godmother places the wedding vase in front of the bride and groom. The bride drinks out of one side of the wedding vase and the groom drinks from the other. Then, the vase is passed to all in the room, with the women all drinking from the bride’s side, and the men from the groom’s.

After the ritual drinking of the holy water and the prayers, the bride’s family feeds all the groom’s relatives and a date is set for the church wedding. The wedding vase is now put aside until after the church wedding.

Once the church wedding ceremony has occurred, the wedding vase is filled with any drink the family may wish. Once again, all the family drinks in the traditional manner, with women drinking from one side, and men the other. Having served its ceremonial purpose, the wedding vase is given to the young newlyweds as a good luck piece.

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.

Rita Casiquito Family Tree - Jemez Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Rita Casiquito Magdalena (c.1900-)

- Juanita Fragua (1935-) and Manuel Fragua

- Betty Jean Fragua (1962-2022)

- Clifford Fragua

- Glendora Fragua (Daubs)(1958-)

- Jeronima Shendo