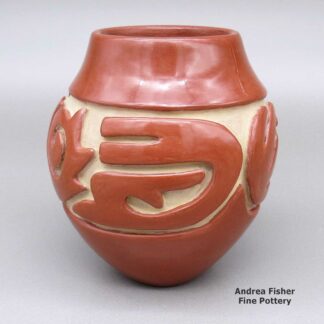

| Dimensions | 3.5 × 3.5 × 2.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Kevin Naranjo Santa Clara Pueblo |

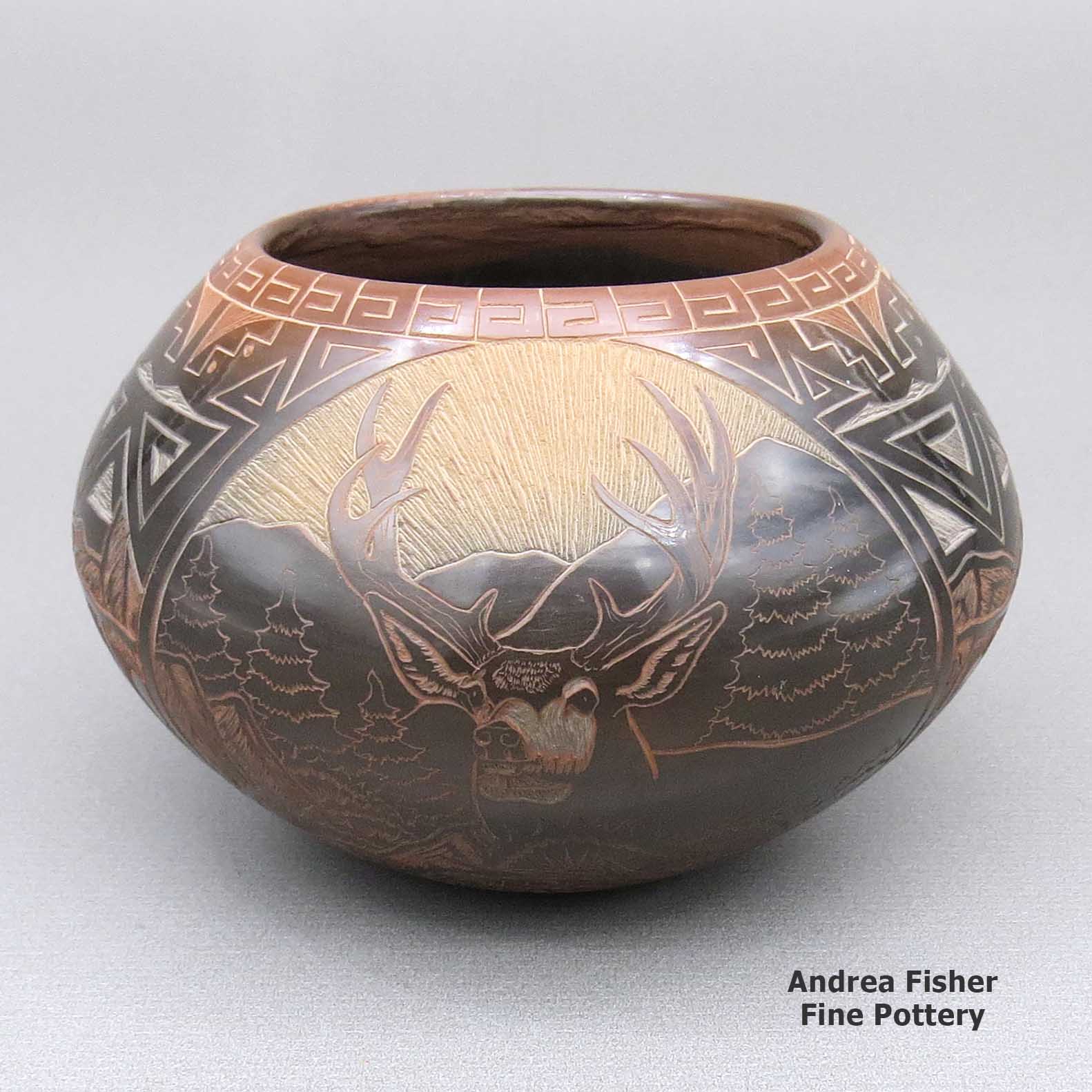

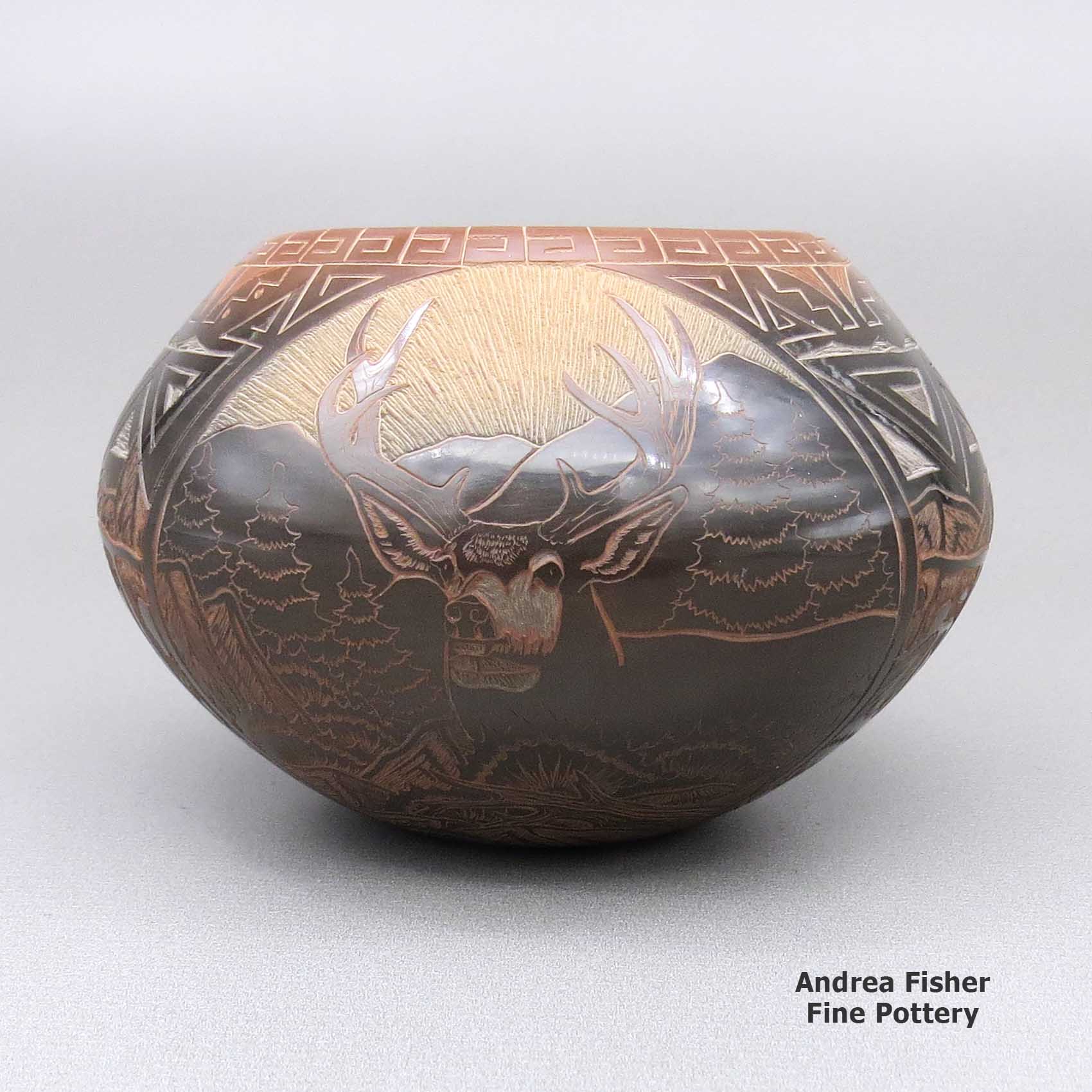

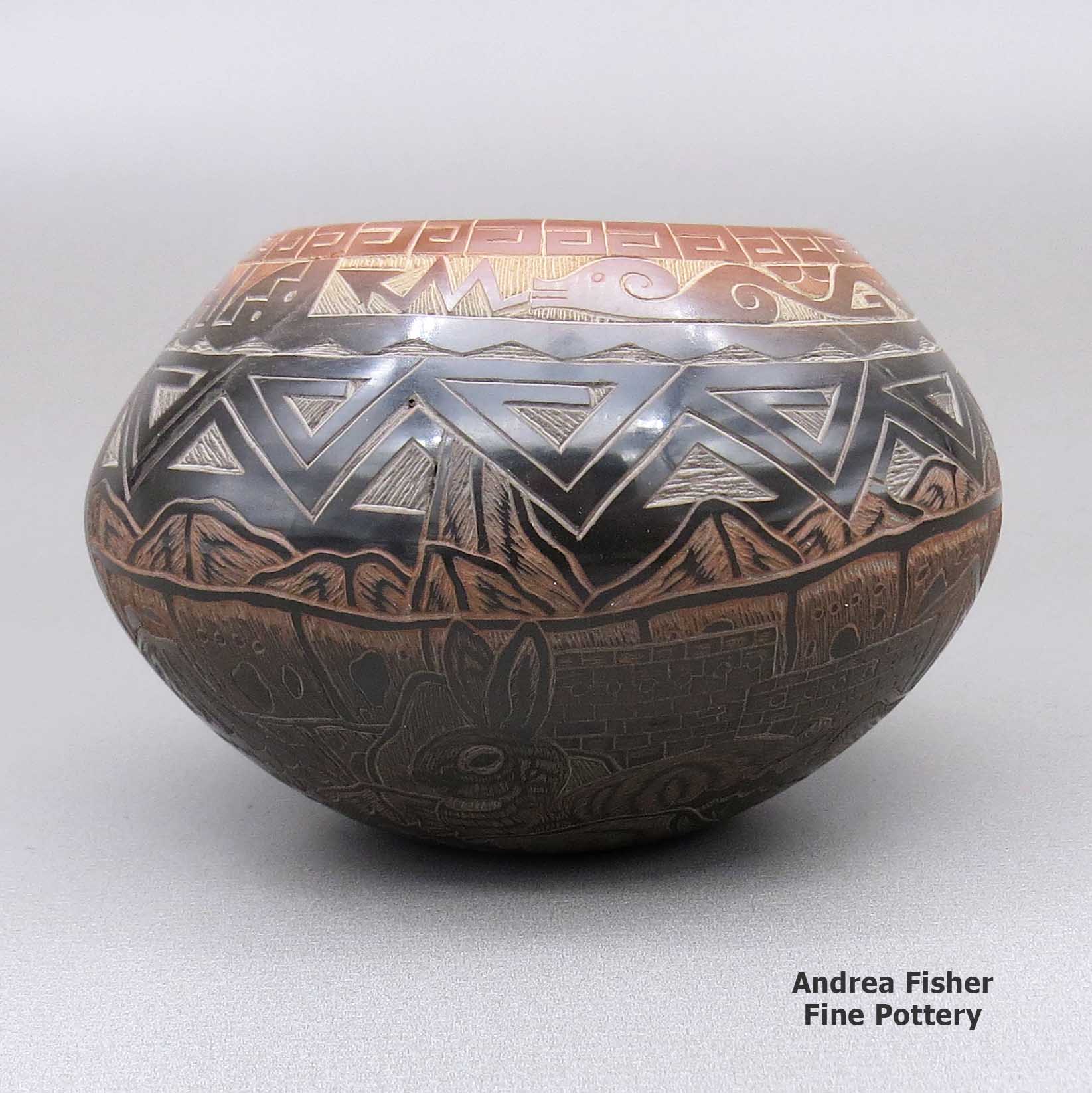

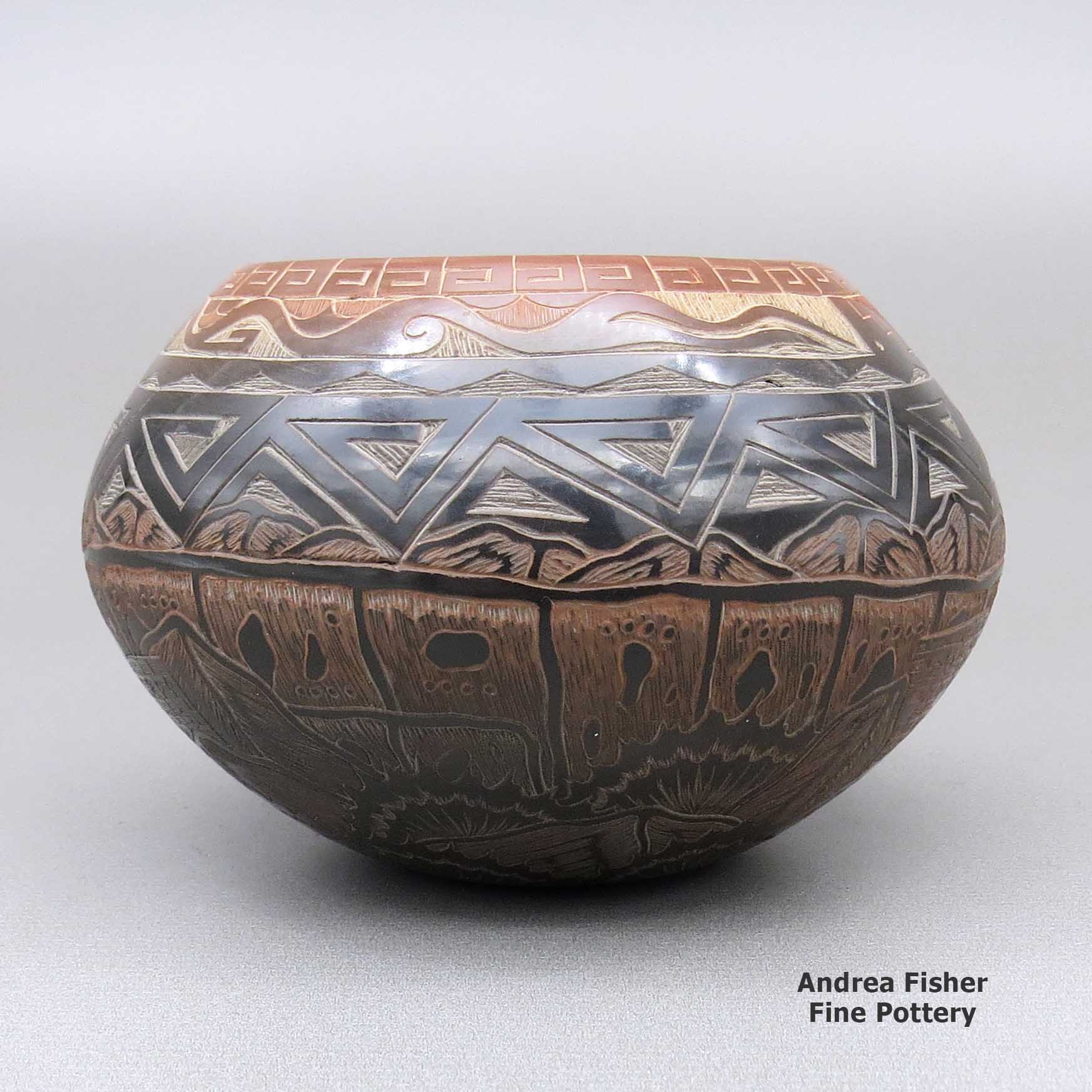

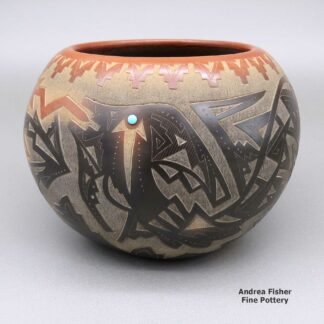

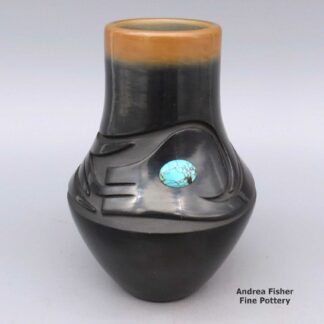

Kevin Naranjo, nmsc3a050, Black bowl with sgraffito geometric design

$1,150.00

A black bowl with a sienna rim and a sgraffito deer, avanyu, rabbit, pueblo and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Naranjo, Kevin

Born in 1972 at Santa Clara Pueblo, Kevin Naranjo was given a Tewa name meaning Turquoise Mountain. He says he was inspired to learn the ancient tradition of hand coiling pottery by the time he was four. That inspiration came from his family and his love of nature.

Born in 1972 at Santa Clara Pueblo, Kevin Naranjo was given a Tewa name meaning Turquoise Mountain. He says he was inspired to learn the ancient tradition of hand coiling pottery by the time he was four. That inspiration came from his family and his love of nature.Kevin was born into a family of famous potters, including Luther Gutierrez (his great-grandfather), Dolores Curran (a maternal aunt) and Geri Naranjo (his mother). Geri is renowned for her miniature sgraffito (fine line incised) pottery, the traditional methods of which she taught to both Kevin and his sister, Monica Naranjo.

Specializing in hand coiled black and sienna sgraffito pottery, Kevin gathers his clay from sacred grounds within Santa Clara Pueblo. He digs and prepares the clay, hand-coils and shapes his forms, then lets them dry for a few days. Then he stone polishes the surfaces and ground fires his pottery using an oxygen-reduction process to make the black canvas for his designs. After firing, he etches the pot to create wonderful scenes of wildlife that live in the area of his home at Santa Clara.

The first piece he made as a child was a dinosaur. He remembers it well: it sparked an interest in molding animal figurines. That first inspiration and practice evolved until now his pottery embodies beautiful symmetry, graceful lines and finely executed sgraffito designs like the avanyu (water serpent), kiva steps and the feather pattern. Additional figures such as bears, eagles, bighorn sheep, deer and elk are incorporated into backgrounds of pueblo ruins and mountain views.

For several years, Kevin collaborated with Tricia Pena from San Ildefonso Pueblo. Her grandfather, the late Encarnacion Pena, was a member of the original San Ildefonso School of Painters.

Kevin has consistently earned awards for his sgraffito and miniature pottery since starting to compete in 1994. He's most proud of the First Place and Best of Division ribbons he earned in the Miniature Sgraffito category at the 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market. He'd earned his first First Place ribbon at the 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market with a burnished black Miniature Sgraffito piece.

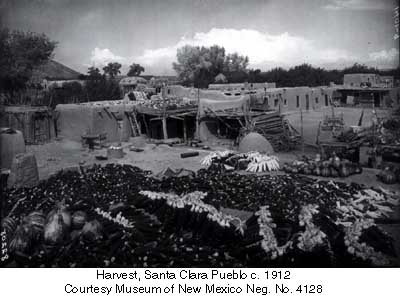

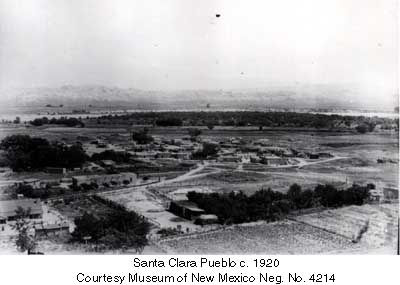

A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

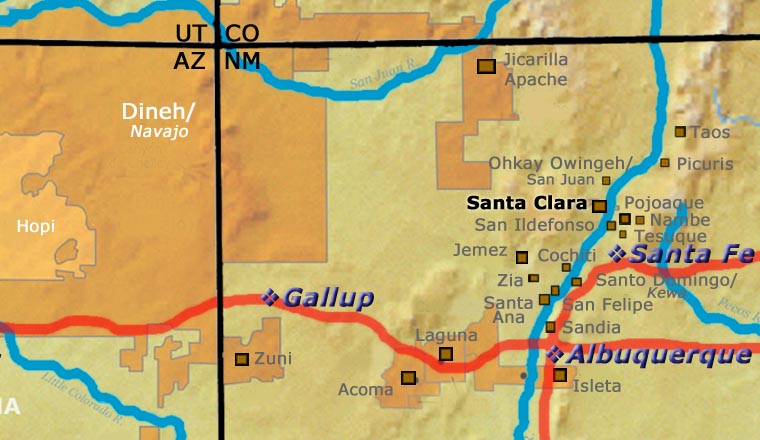

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

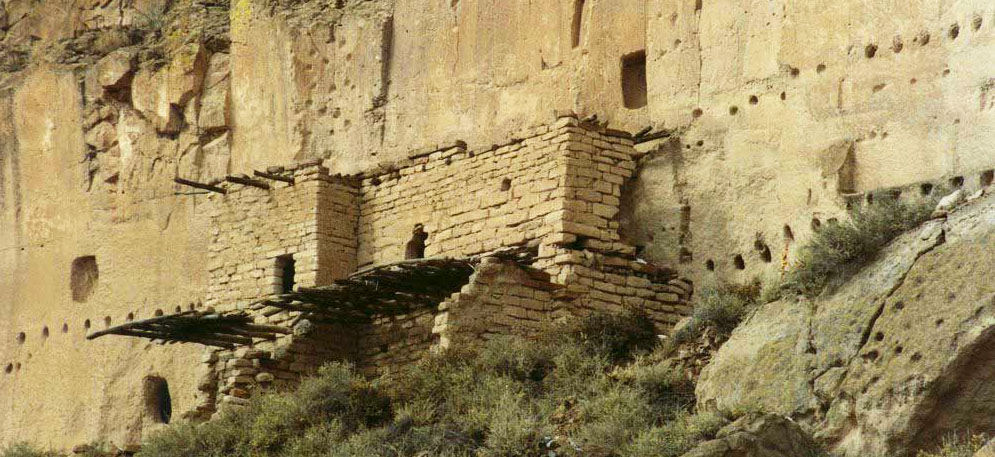

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About Sienna

Sienna is a color achieved on traditional pottery by some Northern Tewa potters through manipulations of their firing process. For centuries, the Northern Tewa have made their pots using a base clay to make the form and then put an iron-bearing slip on the surface. When they polish that slip, it gives them a good background for their designs and fires to produce deeper colors. In a normal oxidizing fire, that iron-bearing slip with turn red as the pot heats up and it will retain that red after the pot cools. To turn the same pot black in the firing, they pour powdered manure on the fire and create an oxygen-reduction atmosphere.

At any point after pouring on the powdered manure, a piece can be removed from the fire and that oxygen-reduction process will be halted partway through, leaving the piece colored somewhere between a deep red and a deep black: sienna.

Some potters fire their pieces to be black, do whatever design work they have in mind and then come back with a blowtorch to "enhance" them. At a high enough temperature, the clay will re-oxygenate and start to turn sienna. It won't turn as red again as it would have been without going through the oxygen reduction process. To get a glossy black pot and retain some of the glossy redness, potters will use things like aluminum foil to cover sections of their pieces and then fire them to be black. Places that are unexposed to the high-carbon atmosphere stay red.

Marie Suazo Family Tree - Santa Clara Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Marie Suazo

- Ursulita Naranjo and Alfred Naranjo

- Dolores Curran & Alvin Curran (San Juan) (1953-1999)

- Geri Naranjo

- Kevin Naranjo (1972-)

- Monica Naranjo (Romero)

- Alfred Ervin Naranjo & Jennifer Naranjo (Sisneros)

- Alfred Naranjo (1980-)

- Dolores Curran & Alvin Curran (San Juan) (1953-1999)