| Dimensions | 2.5 × 3 × 4.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, rubbing on bottom |

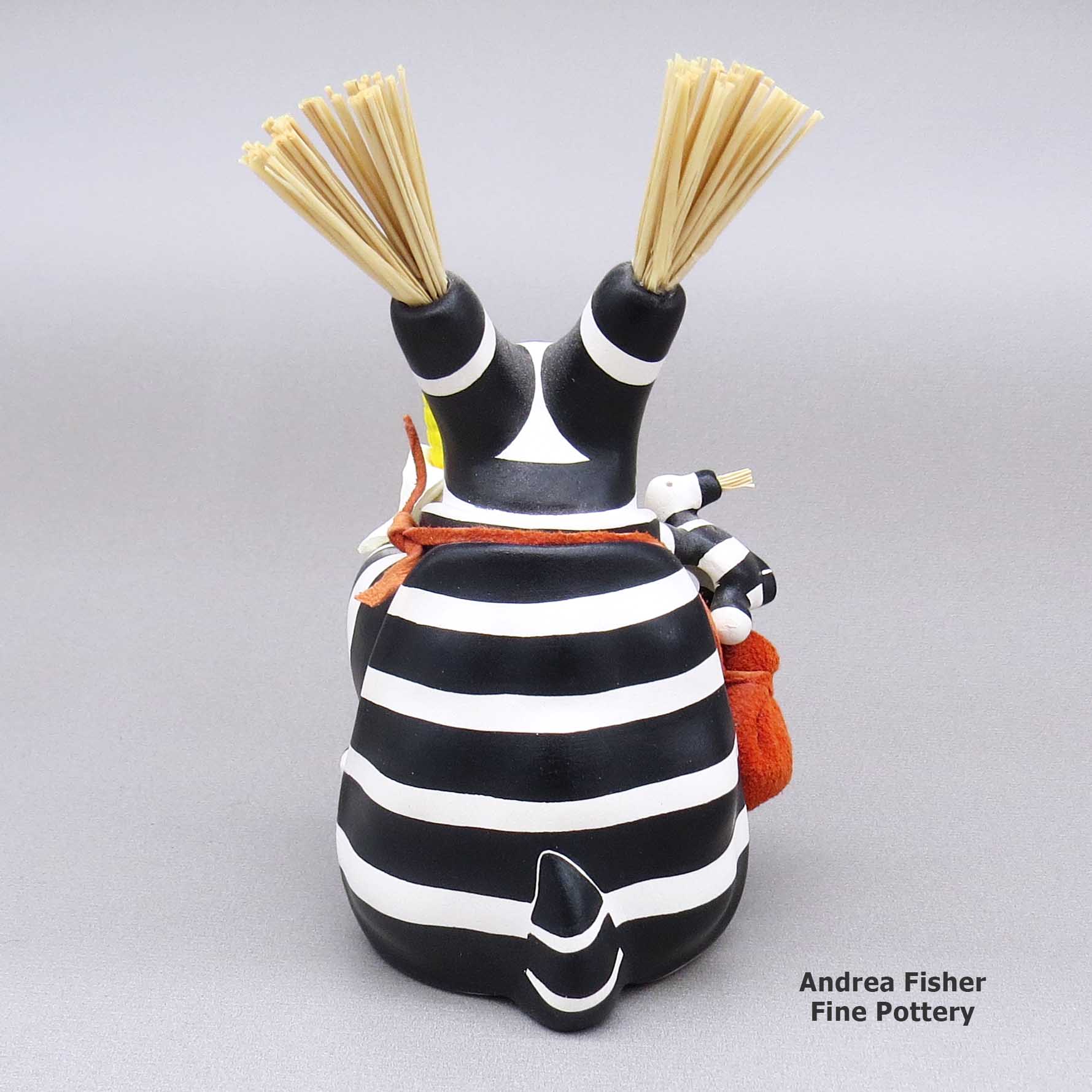

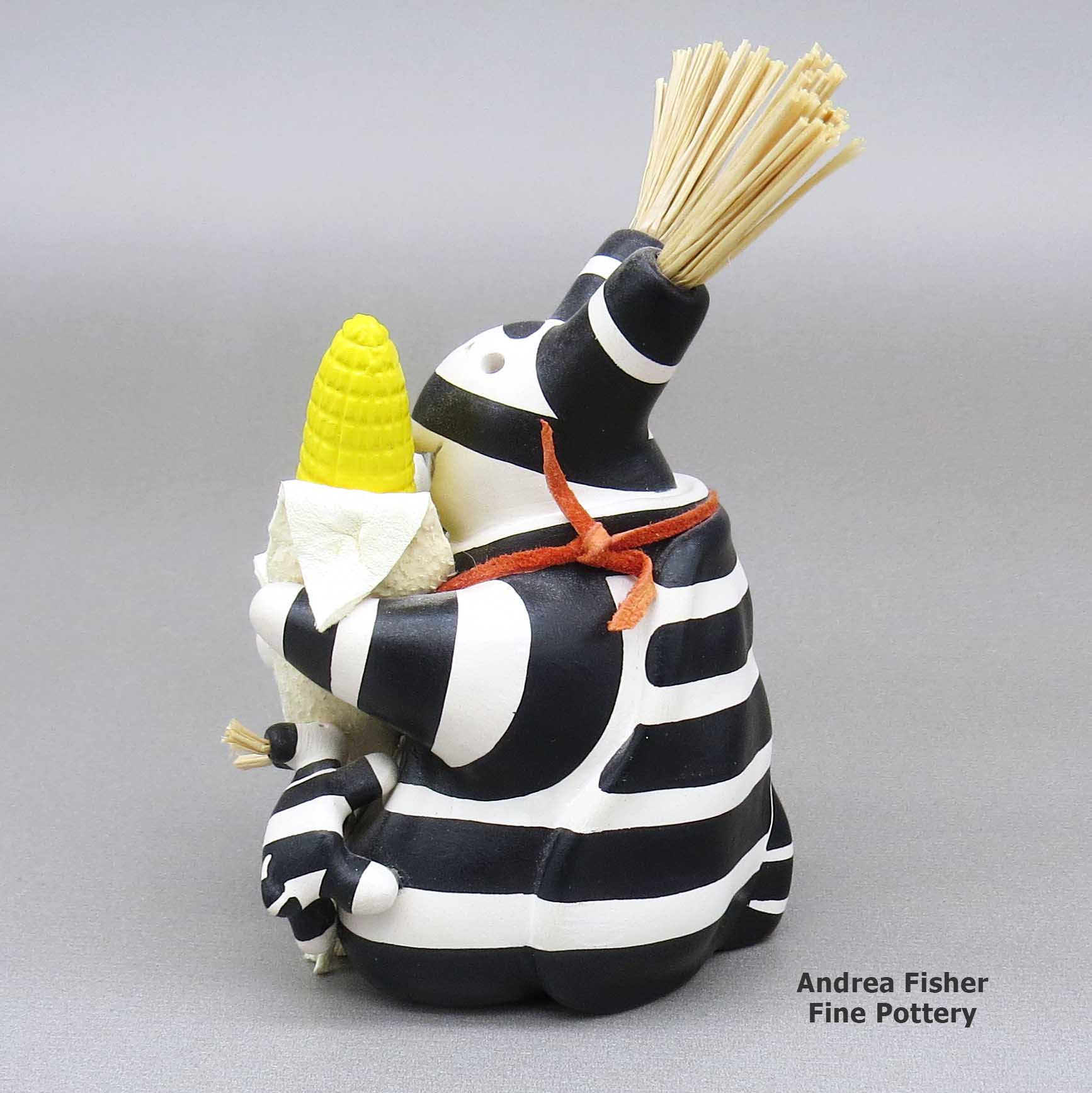

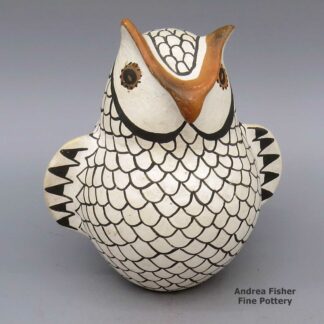

Randall Chitto, jhmm3b161, Turtle koshare storyteller

$195.00

A polychrome turtle koshare storyteller with two hatchlings, an ear-of-corn with a leather husk and a leather pouch

In stock

Brand

Chitto, Randall

First he learned the basics from Hopi potter Otellie Loloma. Then he studied with Fred Pardington. He also continued studying painting and graduated in 1983 with both a Two- and Three-Dimensional Degree in Studio Art. Shortly after that he earned a Fellowship from the Southwest Association for Indian Arts and then a Dubin Fellowship that covered his expenses and allowed him to study at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe for three months.

Randall still paints but he also works in bronze and clay. His works are held in numerous museum collections, including the Denver Art Museum, the Heard Museum in Phoenix and the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, DC, among others.

Randall has served on boards for several non-profit organizations in Santa Fe and, along with his wife Jackie, co-founded the Santa Fe Indian Center. He has also served as vice-chair of the Southwestern Association for Indian Arts.

Some Awards Earned by Randall

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification V - Sculpture, Division A - Representational Sculpture (Realistic/Stylized), Category 1907 - Clay: First Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification V - Sculpture, Division A - Representational Sculpture (Realistic/Stylized), Category 1907 - Clay: Second Place

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market, Classification II Pottery, Division D - Traditional, native clay, hand built, figurative: First Place. Awarded for artwork: "Moving Camp"

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Mary Ann Igna. Awarded for artwork: "Moving Camp"

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Robert K. Liu, PhD. Awarded for artwork: "Moving Camp"

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J -Non-traditional ceramics, all materials, all techniques, with or without decorative elements, any form, any design, Category 1607 - Sets and scenes: Second Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J -Non-traditional ceramics, all materials, all techniques, with or without decorative elements, any form, any design, Category 1608 - Storytellers: First Place

- 2000 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division F - Traditional, Category 1408 - Figures (sets of 2 or more pieces): Third Place

- 1998 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1509 - Single figures (animal and other): First Place

- 1996 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1514 - Storytellers: Second Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1607 - Sets and scenes (nativities and kiva scenes, etc.): Third Place

- 1995 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any forms using non-traditional materials or techniques, Category 1608 - Storytellers (non-traditional): First Place

- 1995 Heard Museum Guild Indian Arts Fair & Market, Classification VII - Pottery, Division C - Effigies and Representations: Best of Division. Awarded for artwork: "Emergence Story"

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any form, Category 1606 - Single figures: Second Place

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any form, Category 1608 - Storytellers: Second Place

- 1991 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division J - Non-traditional, any form, Category 1611 - Miscellaneous: First Place

- 1990 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division K - Pottery miniature, Category 1508 - Figures, one piece: First Place

- 1986 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division H - Non-traditional pottery, Category 1306 - Single figures: First Place

- 1983 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification - Jewelry, Division G - Nontraditional new forms: First Place

About Figures and Figurines

Generally, "Figure" denotes a real or mythic creature, like an owl or human or katsina or Corn Maiden. Whether form or decoration, all Puebloan pottery figures are meant to invoke particular spiritual essences. That's why "effigy" is used almost as often as "figure" to denote these pieces.

Among most Puebloans, the figure of an owl, for example, signifies all the physical and spiritual aspects attributed to the owl. It's a form of prayer to the spirit of "Owl" and the appropriately decorated physical form is meant to make that spirit manifest. However, to the Zuni people an owl is a good omen and to the Tewa people, an owl is a bad omen. Some potters at Santa Clara have made owls anyway, they just shaped and decorated them to reflect that "badness."

That explanation may make more sense in the case of the Corn Maiden as she is a mythic entity whose existence revolves around the most ubiquitous food staple in the Puebloan world: corn (maize). All representations of the Corn Maiden are meant to invoke her benevolence and abundance for their people. Because of her mythical/spiritual nature, different pueblos have slightly different physical forms for her but they all incorporate the basic form of a female human face on an ear of corn.

The potters of Tesuque turned out thousands of muna figures (also known as rain gods)for several decades, until they virutally burned out their pottery tradition. These muna had very specific shapes but were decorated with everything from micaceous slips to incised lines to polychrome geometric designs to poster paints. They were also made purely for domestic American consumption, sometimes delivered by the barrel to be used as prizes and giveaways.

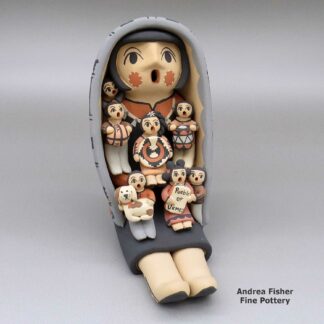

The Storyteller is another figure based on Puebloan tradition: a tribal elder singing the stories of the tribe's oral history to the children. The original was based on the traditional cultural story: a grandfather singing his part of the story in his native language so the children learn both the language and their identity against the backdrop of that history. Shortly, the storyteller form was duplicated in several other pueblos, each pueblo's potters adapting the form to their local situation. In some places, the grandmother became the primary sex of their storytellers. At Jemez, that responsibility was shared between grandmothers and grandfathers. Then some potters in search of new niches in the marketplace branched into making "spirit figure" storytellers, like eagles, ravens, hummingbirds, cats and dogs. Some Zuni potters have made storyteller owls.

Similar to the Storyteller is the Story Time: a set of separate children displayed around a larger central singing figure.

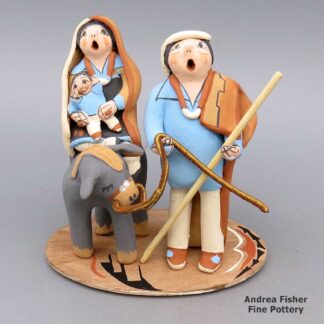

The Nativity set (also known as nacimiento) is a set of figures based on the intersection of Puebloan mythologies and stories they heard from Christian missionaries. Those potters who make them also tend to favor dress, shapes and designs that reflect their own heritage(s). The first few nativities made at Tesuque Pueblo were decorated with Spanish colonial costumes but that soon changed and every nativity made since has a distinct blend of Native American and Christian, with no other reference to colonialism. The "Singing Angel" (a single standing figure with outstretched wings and hands clasped together in prayer) and "Flight to Egypt" (usually depicting Mary with a baby Jesus on the back of a donkey and a standing Joseph nearby holding the rein) are similar mixes of tribal and Christian figures. The miniature nativities made by Santa Clara/Dineh artist Linda Askan clearly show Dineh religious influence in the headresses worn by Joseph, the angel and the three wise men. At the same time, the Dineh Folk Art nativities made by Jonathan Chee are based on the realities of daily Dineh life: the three wise men wear wide-brim hats and blue jeans, and bring gifts of salt and 50-pound bags of flour.

Pueblo and Dineh artists also make a full zoo of domesticated, farm and wild animal figures: horses, donkeys, cows, chickens, pigs, sheep, turkeys, giraffes, elephants, dogs, cats, mermaids, women-dressed-up-and-taking-selfies and cowboys among them.

About the Storyteller

Historically, clay figures have been present in the Pueblo pottery tradition for more than a thousand years. However, figures and effigies were denounced as "works of the devil" by the Spanish missionaries in New Mexico between 1540 and 1820. Before and after that time the art of making figurative sculpture flourished, especially at Cochiti Pueblo. At Cochiti, the forms of animals, birds, caricatures of outsiders and, more recently, images of mothers and grandfathers telling stories and singing to children have multiplied.

The "storyteller" is an important role in the tribes as parents are often too busy working and raising kids to pass on their tribal histories. The Native American people did not develop a written language to record anything for posterity. Some tribes still refuse to create one. The closest thing they had to a written language was recorded on pottery and textiles, in the form of painted designs that decorate that pottery and textiles.

The storyteller's role was to preserve and retell and pass down the oral history of his people in their native language. In most tribes that role was fulfilled by elder men.

The first recorded storyteller figure was created in 1964 by Cochiti Pueblo potter Helen Cordero in memory of her grandfather, Santiago Quintana. She gathered her clay from a secret sacred place on the lands of her pueblo. Then she hand-coiled, hand painted and fired that first storyteller figure the traditional way: in the ground. Helen never used any molds or kilns to make her pottery.

Helen's creation immediately struck a chord throughout all the pueblos as the storyteller is a figure central to all their societies. Most tribes also have the figure of the Singing Maiden in their pantheon and in many cases, the mix of Singing Maiden and Storyteller has blurred some lines in the pottery world.

Today, as many as three hundred potters in thirteen pueblos have created storytellers. Their storytellers are not only men and women but also Santa’s, mudheads, koshares, bears, owls, eagles and other animals, sometimes encumbered with children numbering more than one hundred! Each potter has also customized their storyteller figures to more closely reflect the styles and dress of their own tribes, often even of their own clans.