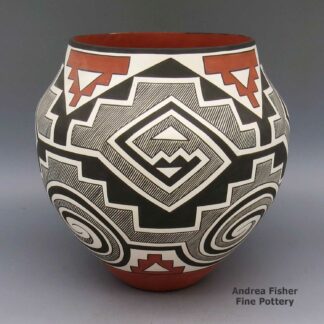

| Dimensions | 19 × 19 × 19 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has flaking of paint and rubbing on bottom |

| Date Born | 1988 |

| Signature | to the glory of God! Richard Zane Smith Wyandotte descendant |

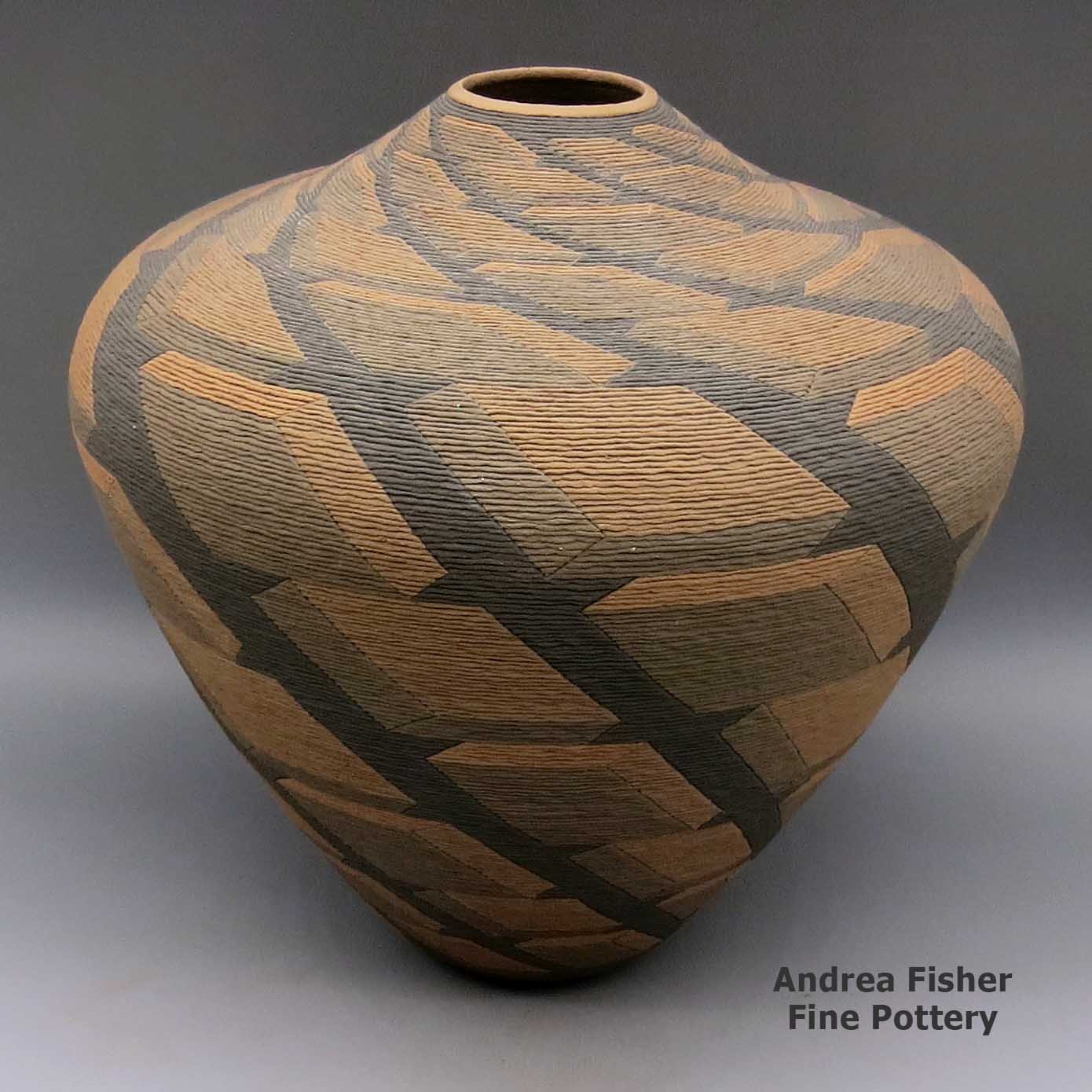

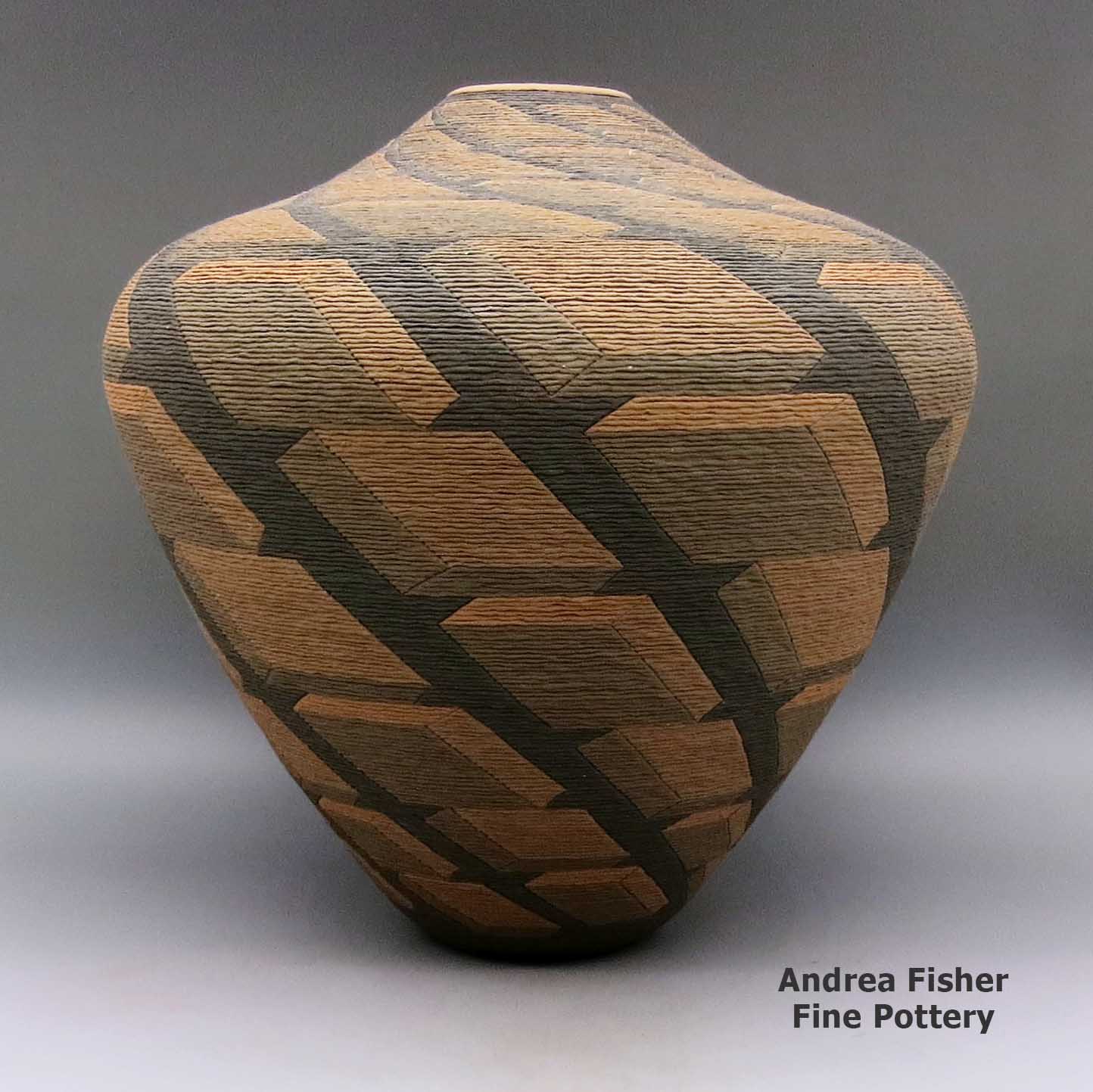

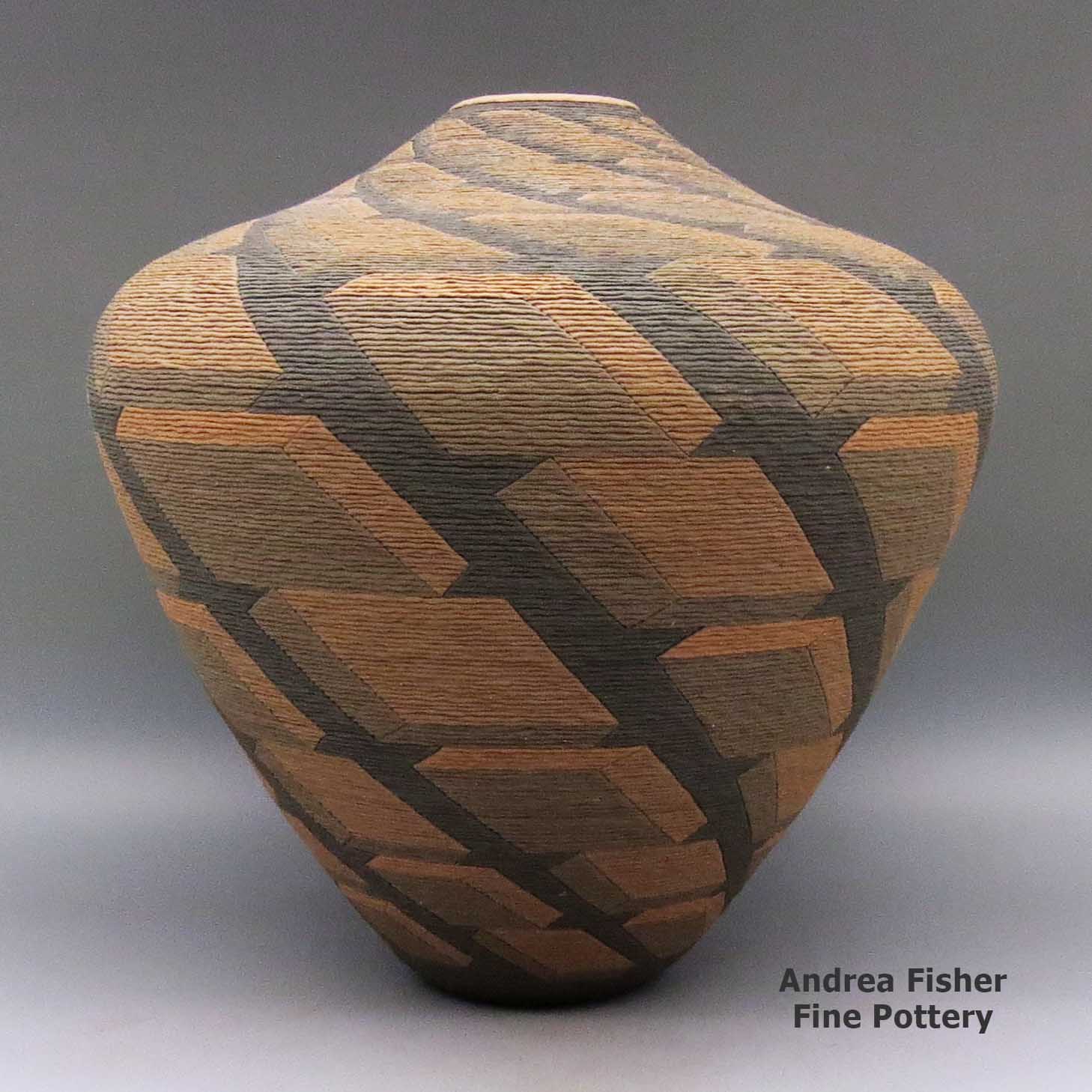

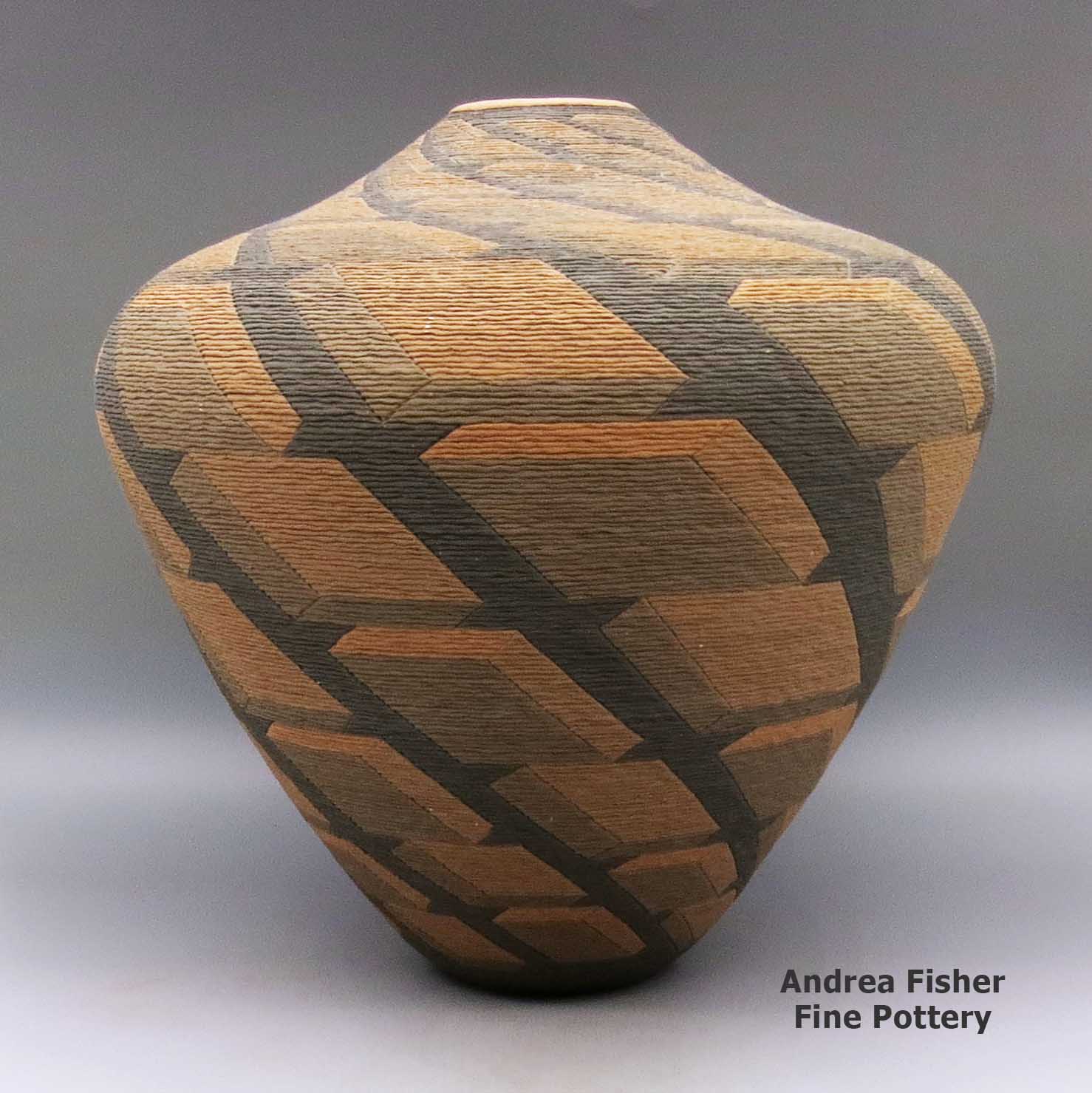

Richard Zane Smith, zzmm2l160, Jar with sgraffito geometric design

$15,000.00

A large jar with an unsmoothed coil exterior and a sgraffito-and-painted three-dimensional geometric design

In stock

Brand

Smith, Richard Zane

Sǫhahiyo (he has a good road)

Sǫhahiyo (he has a good road)

- Born August 18, 1955 - raised in the St. Louis, Missouri area

- 1973 University City High School, University City, MO.

- 1975 Meramec Community College, Associate of Art Degree, St. Louis, MO

- 1976 Kansas City Art Institute; studied ceramics, Kansas City, MO

SELECTED PUBLICATIONS

- "Spoken Through Clay" - The Eric S. Dobkin Collection, 2017, book, pp. 300-307

- "American Art Collector" - magazine, issue 118, August 2015 article pp. 162-163

- "The Olson- Brandelle North American Indian Art Collection" - Augustana College, 2010, pp. 254-257

- "Maori Art Market 2009" - published book/catalog by "Toi Maori Aotearoa" pp. 144-45

- "Design" by Steven Aimone, Lark Publishers, 2004, pp.20. "In Touch with the Past" - Southwest Art Magazine, Aug. 2003, pp. 154-158.

- "Changing Hands, Art without Reservation, 1" - American Craft Museum, 2002, Forwards by McFadden & Taubman, Merrell Publishers, pp.11,19, 26, 58, 149, 158, 180, 201.

- "Contemporary Ceramics" - by Susan Peterson, Published by Watson Guptill, 2002

- "Hand Built Ceramics" - by Kathy Triplett, Published by Lark Books, 1997, pp. 29, 46, & 50.

- "The Craft and Art of Clay" - by Susan Peterson, Published by Overlook Press, 1996, pp. 180.

- "The Pottery of Richard Zane Smith" - Ceramics Monthly, Sept. 1992, pp. 58-61.

- "Modeling" (Arts and Crafts series) - Wayland Publisher, England.

- "Fired Up! Making Pottery in Ancient Times" - Runestone Press, 1993, pp. 23 & 35, by Rivka Goren.

- "Art of Clay" - edited by Lee M. Cohen, Clear Light Publishers, Santa Fe, NM, 1993, pp.113-119.

- "Beyond Tradition, Contemporary American Indian Art and Its Evolution" by Jerry and Lois Jacka, Northland Publishing So. 1988, pp. 99 & 194

- "The New Individualists" - Jerry & Lois Jacka, Arizona Highways, May 1986, pp. 30 & 46.

- "The Eloquent Object" - Thomas & Marcia Manhart, eds. Tulsa Philbrook Museum of Art, 1987, pp. 35 & 64.

Ongoing SELECTED EXHIBITS and MUSEUM COLLECTIONS

- 2018 - Commissioned art work for display in the Shawnee Tribe Cultural Center

- 2018 - August show and demo at Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery Gallery

- 2017 - August Show and Demonstration at Andrea Fisher Fine Pottery

- 2017 - Heard Museum exhibit, "Beauty Speaks for Us" showing till April

- 2017 - Autry Museum of the American West, Los Angeles Ca . a piece for their permanent Collection

- 2016 - commissioned work for the cultural resource museum - Eastern Shawnee Nation of Oklahoma

- 2015 - commissioned piece for the Muscarelle Museum of Art at the College of William and Mary, Virginia

- Through 2016 - continual shows - Blue Rain Gallery, Santa Fe, NM.

- 2014 - Kokiri Putahi 2014 7th gathering of International Indigenous Visual Artists, New Zealand - Te Runanga A Iwi O Ngapuhi art exhibition in the Toi Ngapuhi Exhibition

- 2009 - Invited guest artist - Maori Art Market 2009 Porirua, New Zealand

- 2009 - National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, for their permanent collection

- 2007 - Heard Museum exhibit, Phoenix AZ

- 2007-08 - New York, NY and Chicago IL , S.O.F.A. Shows , Blue Rain Gallery

- 2006 - Palm Springs California, Blue Rain Gallery of Santa Fe, traveling group exhibit

- 2003 - "NDN ART" Booksigning and Exhibit. College of Santa Fe, Santa Fe, NM

- 2003 - American Craft Museum, NY, NY., Permanent Collection

- 2002 - "Changing Hands: Art without Reservations" American Craft Museum, NYC, NY

- 2001 - Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ Solo Exhibit

- 2000 - San Francisco, CA , Blue Rain Gallery of Santa Fe, traveling group exhibit

- 1998-99 - "Head & Heart & Hands", touring exhibition presented by the Kentucky Art and Craft Gallery, Louisville, KY

- 1997 - "Celebrating American Craft", exhibition Kunstindustrie Museum, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 1995 - Wyandot County Historical Museum, Bonner Springs, KS

- 1994 - Philbrook Museum, Tulsa, OK. Permanent Collection.

- 1991 - Gallery 10, "New Works", solo exhibition, Scottsdale, AZ

- 1991 - Kavesh Gallery, "The West in Image and Object", Ketchum, ID

- 1991 - San Diego Museum of Man, "All is More Beautiful", group exhibit and lecture.

- 1987-89 - "The Eloquent Object", traveling exhibition of the Philbrook Musuem of Art, Philbrook Art Center, Tulsa, OK

- 1989 - Denver Art Museum, Denver, Co., Permanent Collection

LECTURES AND DEMONSTRATIONS

- 2017 - Wendat pottery workshop and lecture at the University of Toronto, Mississauga, Ontario

- 2016 - Guest speaker at the opening of Indigenous Beauty, Masterworks of American Indian Art from the Diker Collection, Toledo Museum of Art, Toledo OH

- 2014 - slide presentation Philbrook Museum, Tulsa, OK

- 2014 - Kokiri Putahi, 2014, 7th gathering of International Indigenous Visual Artists, New Zealand - Te Runanga A Iwi O Ngapuhi, art exhibition in the Toi Ngapuhi Exhibition

- 2012 - Presentation given "Circling Back, Recovery of Wendat-Wyandot(te) Lifeways", (Congrès d'études wendat et Wyandot)Wendat and Wyandot Studies Conference Wendake, PQ, 13-16th June 2012

- 2009 - Lecture / powerpoint presentation at "Toihoukura" Art School in Gisborne, New Zealand - also at "Te Wananga o Aotearoa" Whirikoka Campus, also in Gisbourne, New Zealand

- 2006 - participated in Panel discussion of three Native American artists: Jody Folwell, Roxanne Swentzell and himself at the Denver Art Museum

- 2003 - Pottery Demonstration, slide/lecture. Workshop. Philbrook Museum, Tulsa, OK

- 2001 - Pottery Demonstration, slide/lecture. The Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ

- 2000 - Kanehsatake High School, Mohawk Reserve, Quebec, Canada. Demonstration and slide presentation.

- 1998 - San Juan Campus, Blanding, UT, Lecture, slide presentation, and demonstration.

- 1998 - L'Abri Conference on Creation and Culture, Rochester, MN. slide presentation, and demonstration.

- 1994, 1996, 1997 - Meramec Community College, St. Louis, MO, slide lecture and demonstration.

- 1991 - Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, KS. Lecture and demonstration.

- 1991 - University of Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada. Lecture and week demonstration.

- 1991 - National Council of Education for the Ceramic Arts, Arizona State Univ. Tempe, AZ. Demonstration.

- 1990 - Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, "Historic & Modern Pueblo Ceramics: Tradition and Change", sponsored by Recursos de Santa Fe, NM

TEACHING (art related)

- 2018 - One month program at Spiva Center for the Arts, Joplin, MO, for 3rd graders

- 2018 - Intense two week pottery instruction of Wendat/Iroquoian pottery techniques with Jennifer Stevens

- 2017 - Pottery lessons off and on through the year with Carrie Lind and others

- 2016 - At my studio, Shawnee ancestral pottery workshops with the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- 2015 - At my studio, Revitalization pottery workshop with the Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- 2012 - At my studio, Seneca/Cayuga , Iroquoian pottery techniques

- 2010 - At my studio , traditional Wendat/Iroquoian pottery workshop, 8 weeks

- 2006 - Instructor for a non-federally-recognized Cherokee group, 8 week traditional pottery workshop - Also an Eastern Shawnee, traditional pottery workshop

- 2001, 2003, 2007 - Wendake Reserve CDFM, Community College, Lorette, PQ, Canada, week-long workshops

- 2003-04 - Pottery Workshop for tribal members, Wyandotte, OK

- 2001 - Instructor, Rehoboth High School, Gallup, NM. week-long Summer Pottery Workshop

- 1998 - Instructor, "From the Earth" One week workshop, San Juan Campus, Blanding, UT

- 1982 - Instructor, "Anasazi Pottery Traditions", Northland Pioneer College, satellite program, one semester, Ganado, AZ

- 1978-79 - Art Instructor, Sun Valley Navajo Mission School, Holbrook, AZ

HONORS

- 2010 - First Peoples Fund: 2010 Community Spirit Awards (for clay, storytelling and Wyandot songs for children)

- 2007 - Honored at Wyandotte Nation Pow-wow (for Wyandot language revitalization effort and teaching language to children in The Wyandotte Public School district - 7 years total)

- 1983 - Heard Museum Guild: Native American Art Show - Best of Pottery

- Since 1985 -- I haven't entered any art competitions

VOLUNTEER

Teaching (Wyandot language and cultural arts)- 2018: Story telling for the pre-school at the Learning Center in Grove, OK

- 2005-2016: Storyteller for public schools in Grove and Wyandotte, OK

- 2013-2017: Wandat Language Facebook site to teach and share Wandat Language material

- 2005-2012: Teaching Wandat language/culture in the Wyandotte Public Schools, Wyandotte OK

- 2009-2012: Teaching Wandat language to preschoolers, Turtle Tots preschool, Wyandotte OK

- 2012-2013: Teaching adult Wyandot language class on Thursday evenings

- Presently: Holding occasional traditional bowmaking sessions (ex. Our Wandat Green Corn 2014)

In Richard's own words

"I am thankful to my family and for the support and encouragement, and my parents who gave me an insatiable appetite to seek the truth. To All my First Nations brothers and sisters, and all the children who urge me on by their love of singing in Wyandot and their love of storytelling… "I'm most grateful to my wife Carol, my constant companion for 37 years, her steadfastness, her friendship, her patient love and thoughtfulness. "Above all I'm thankful to our Creator who is more mysterious and greater than anything I could have ever imagined. "I am a Wyandot. We never divided ourselves in pieces or parts. I know my family history and am proud to be an active tradition keeper as we seek to revive our ceremonies, our dances, our songs and our language."A Short History of the Wyandot People

Before the arrival of Columbus, the ancestors of today's Wyandot(te) lived mostly in the countryside stretching north from the north shore of Lake Ontario to the north and east shores of Georgian Bay (on Lake Huron to the north). Members of the tribe were scattered as far south as the Kanawha River in central West Virginia but as Europeans flooded in from the east in the 1600s and 1700s, they were pushed out, forced to move north and rejoin the rest of their tribe.

In their Ontario homelands, there were basically five nations making up the Huron Confederacy. Most of today's survivors we now know as Wyandot but originally the tribe was known as Huron, based on their occupation of lands to the north, east and south of Lake Huron.

Around 1600 the tribe was comprised of two primary groups: the Huron Confederacy (of the 5 nations) and their neighbors to the south and southwest, the Tionontate (also known as the Tobacco people, after their principal commodity crop). Like the Huron, the Tionontate were longhouse dwellers and spoke a very similar dialect. The Anishinabe, to the north and east, were also longhouse dwellers and spoke a similar dialect.

When news of the French arrival in North America reached the Huron, some of them decided to go and meet the newcomers. Samuel de Champlain was exploring the upper reaches of the St. Lawrence River at that time. The two groups came together in 1609 and a political and trade alliance was forged. Within 20 years of that fateful meeting with Champlain, the tribe was reduced from about 30,000 members to maybe 12,000 due to diseases brought by the French that the indigenous people had no immunity to. At the same time, the Dutch and English presence was having similar impacts among the tribes south of the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes. That effect mushroomed after the British took over the Dutch colonies in the mid-Atlantic area.

The drop in population was so catastrophic to the Huron that whole villages, families and clans disappeared and agricultural lands were abandoned. Jesuit missionaries were spreading everywhere and they further fractured the tribe into "redeemed" and "unredeemed" heathens. As the Europeans encouraged the fur trade in the New World and beavers were pushed almost to the brink of extinction, conflict among the tribes increased significantly. As the most advanced trading nation in the area of French claim, the French invested more in their alliance with the Huron while the English allied themselves with the Hurons' mortal enemies: the Seneca and the Haudensaunee (Hutinǫhšǫdih) Iroquois to the west and south.

A difference between the Dutch/English and French invasions: the Dutch and English would trade firearms with anyone for beaver pelts while the French required conversion to Christianity before allowing any trade in firearms. When push came to shove (as it did with the French & Indian War), France's allies were outgunned and outnumbered by Britain's allies. In the aftermath of that conflict, France's New World allies were made to suffer further.

The Huron enjoyed good trade and amicable relations with their Anishinabe neighbors (the Anishinabe even shared longhouses with the Huron and some families straddled tribal lines). Neither tribe wanted any disruption of that. However, the disparity in access to firearms and the growing scarcity of beaver led the Haudensaunee Iroquois to attack two Huron villages in present-day Simcoe County, Ontario, killing about 300 people on March 16, 1649. By May 1, 1649, the Huron had burned 15 more of their own villages to prevent their stores from being taken and used by their enemies. Many of those people fled into surrounding areas where they were taken in as refugees by other tribes. About 10,000 Huron fled to Christian Island in Georgian Bay but most of those starved to death over the following winter. Many of the survivors of that winter made their way downstream along the St. Lawrence and settled at Wendake, near Quebec City, where their descendants remain to this day (these are today's Wendat people, a Canadian-government recognized First Nation).

As the massive Iroquois and Seneca war party made its way around in Huron territory in 1649, they attacked other Huron and Tobacco people villages. That resulted in the Bear Clan of the Huron merging with the Tionontate as refugees from both flowed across Lake Huron and Lake Michigan to the area of Green Bay. A couple seasons later most of those moved north and settled in the area of Michilimackinac. Others scattered to the west and south, passing into southeastern Michigan and across Ohio into the Ohio River Valley in the early 1700s. At that point the Huron and Tionontate in the west were essentially one tribe: Wandat. At the time, Wandat meant "people of the village" or "people of the island," but as the 1800s rolled on that definition was reduced to "villager" and the word itself morphed to Wyandot. That's when the name Wyandot came into general usage.

When the American Revolution came along, the Wyandot allied themselves with the British against the Americans and in one of the last engagements of the Revolutionary War (the Battle of Blue Licks, fought 10 months after the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown), they surrounded and defeated the Kentucky militia led by Daniel Boone. During the Northwest Indian War (1785-1795) they fought alongside the British and were signatories to the Treaty of Grenville in 1795 (other signatories to that treaty: Meriwether Lewis and William Clark of the 1804-1806 Lewis & Clark Expedition and William Henry Harrison, later the 9th President of the United States). However, in 1807, along with the Potawatomi, Odawa and Ojibwe peoples, they were led into signing the Treaty of Detroit. Instead of protecting those tribes from continuing encroachment on their lands by Euro-American immigrants and settlers, that treaty ceded most of their holdings in southern Michigan and northwestern Ohio to the government of the United States for a minimal cash payment and annuity. They were allowed to keep small pockets of land in the area but this treaty was the beginning of the forced migrations of the US government policy of Indian removal.

In the 1840s most of the surviving Wyandot people were displaced to Kansas Territory, where they used what remained of the proceeds of their sale of southeastern Michigan and large pieces of Ohio to purchase about 23,000 acres of land from the Delaware (Lenape) in what is now Wyandotte County, Kansas. That purchase happened because the Lenape were grateful for the hospitality they had received from the Wyandot in Ohio when they (the Lenape) were also forced to move west under pressure from incoming Anglo-American colonists. A couple other small pieces of fertile land were granted to the tribe in the early 1840s, along with 32 "floating sections" of land west of the Mississippi River. In 1850 they sold some of their land back to the federal government for almost $127,000 and invested most of those proceeds in government bonds.

In 1853, William Walker was elected the provisional governor of Nebraska Territory (which included Kansas) during an election at the Wyandot Council House in Kansas City. As a leader of the Wyandot people he was also elected by white traders and other outside interests in an effort to preempt federal organization of the territory. Congress refused to recognize Walker's election but the political activity did force Congress to pass the Kansas-Nebraska Act and separate the two into separate territories. That was also necessary in the run-up to the Civil War in order to balance free and pro-slavery votes in Congress. It didn't work out well. That was also a time when the tribe itself divided along pro-slavery and abolitionist lines. There were also major problems with extreme poverty among the tribe's members and with sleazy Anglo-European traders and land-grabbers stealing the land out from under the people. That's how the tribe got broken further into the scattered groups we see today.

By 1855 the official population of the tribe was less than 700 individuals. That year they sold the rest of the 32 "floating sections" (located in Kansas, Nebraska and "unspecified" locations) for $25,600. Surveys were not required and titles became complete at the time of site location (not at all like real estate transfers these days). In the 1940s the federal government began to address a long-standing Wyandot land claim based on their having been forced to sell their Ohio lands for less than fair market value in order to comply with the Indian Removal Act. In 1985 the Bureau of Indian Affairs finally settled the claims by paying $1,600 to each of the approximately 3,600 people in Kansas and Oklahoma who could prove they were descendants of Wyandot originally affected by the Indian Removal Act.

In the United States there is one federally recognized tribe: the Wyandotte Nation, headquartered in Wyandotte, Oklahoma. In Canada there is one Wyandot First Nation: the Huron-Wendat Nation headquartered in Quebec City, Quebec. The Wyandot Nation of Anderton, headquartered in Trenton, Michigan, and the Wyandot Nation of Kansas, headquartered in Kansas City, Kansas, are both unrecognized tribes, even though both are composed of Wyandot descendants.

We are only aware of two Wyandot potters: Richard Zane Smith and his nephew, Jamie Zane Smith.

Images are available under the Creative Commons ShareAlike License

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.