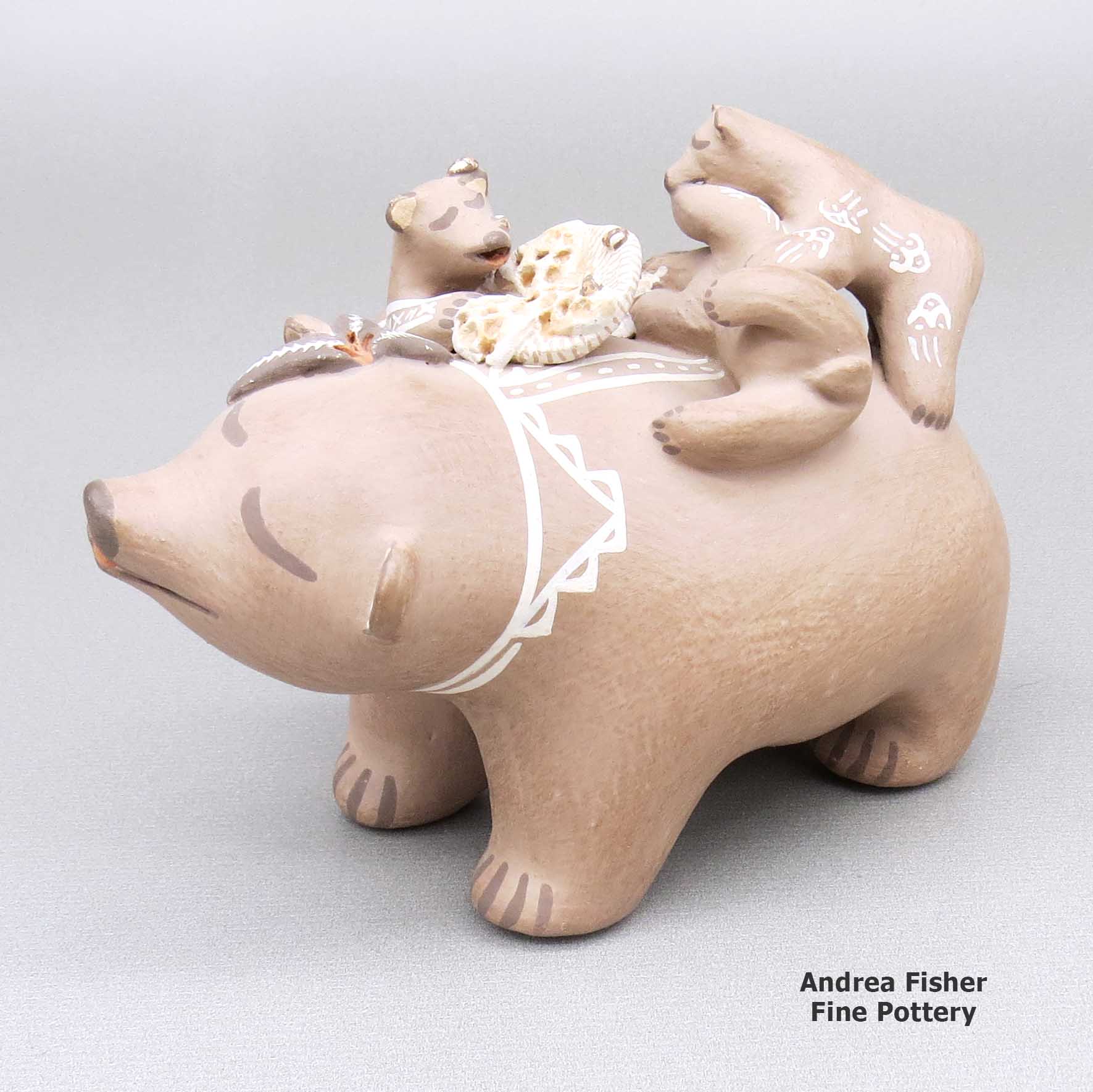

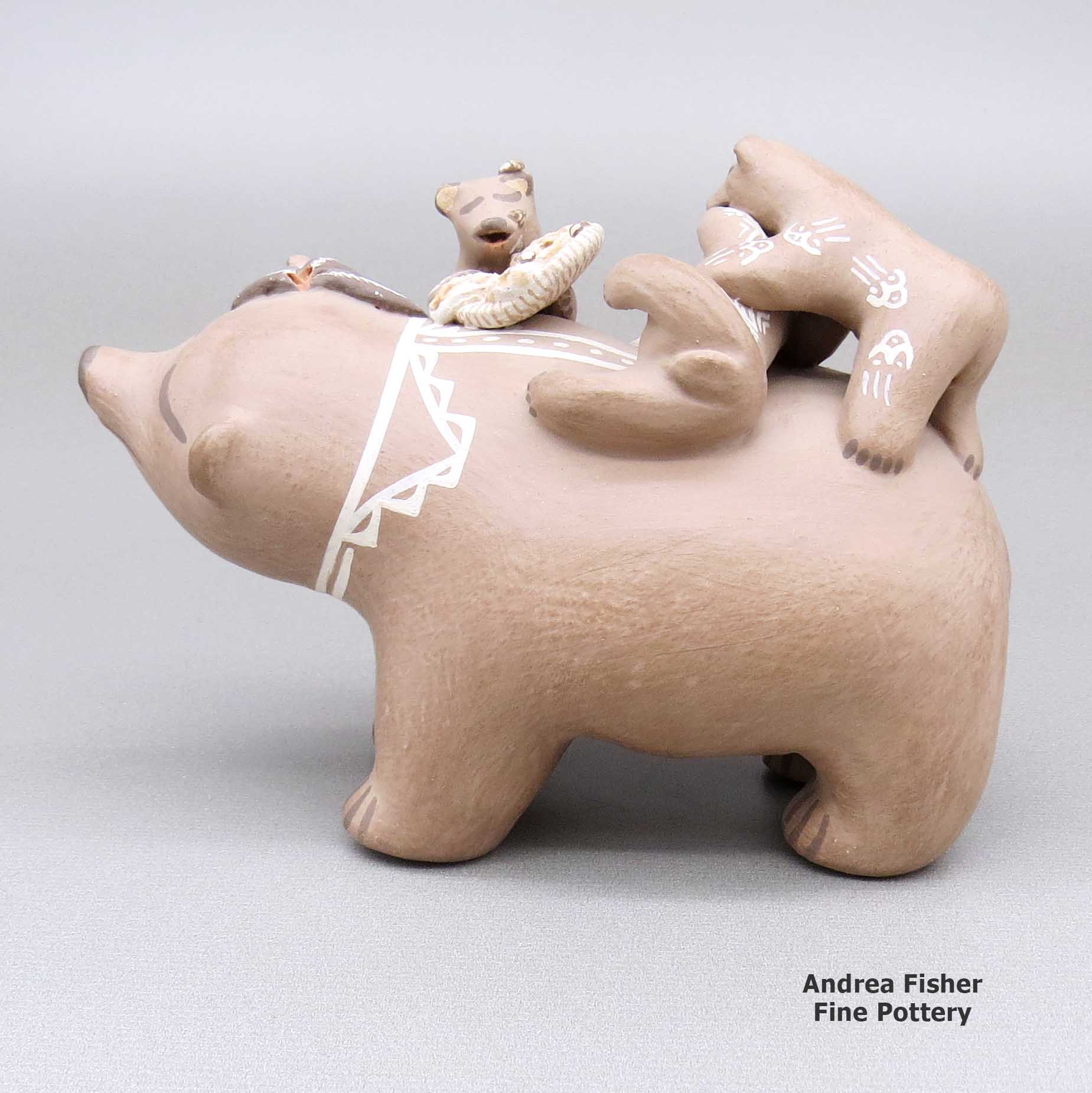

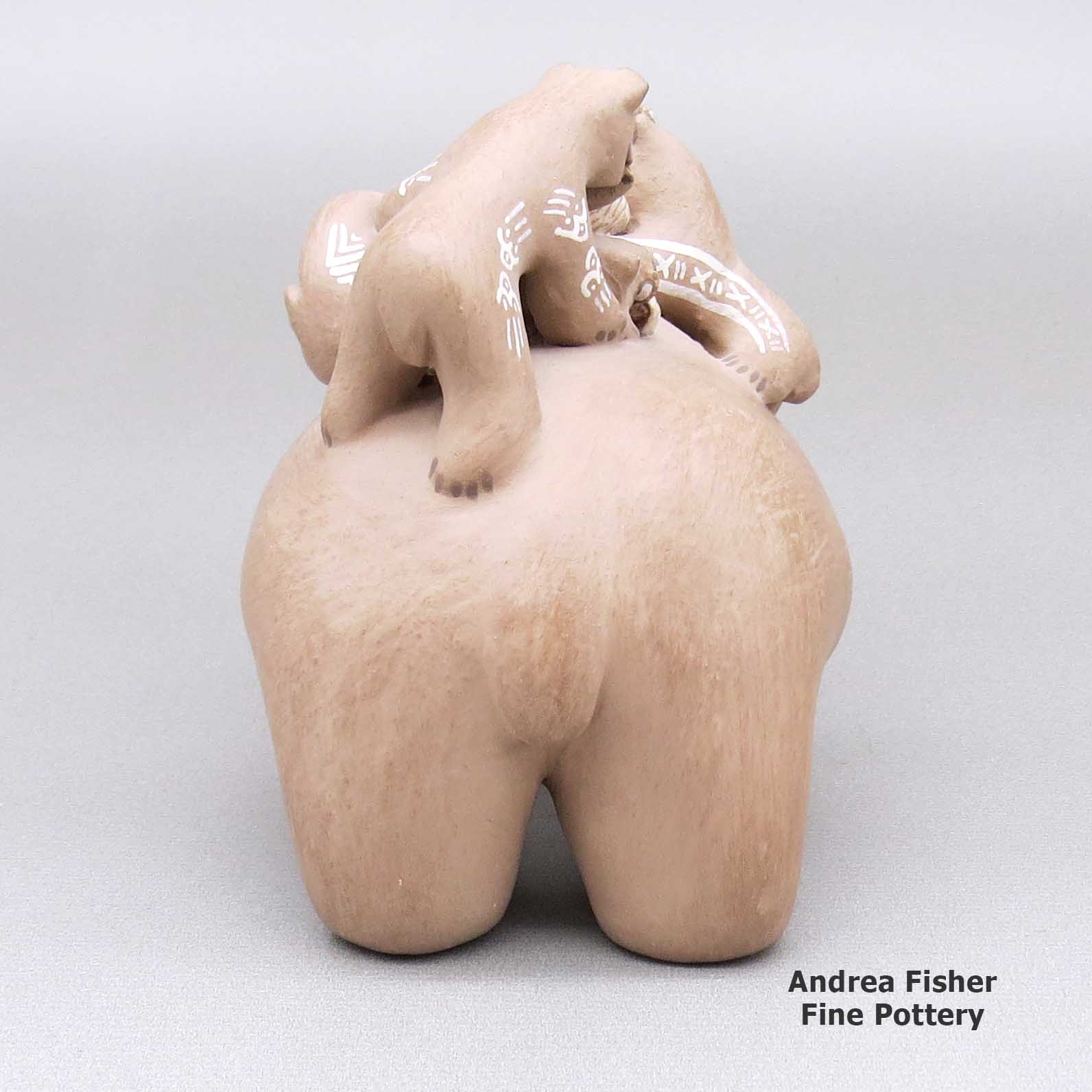

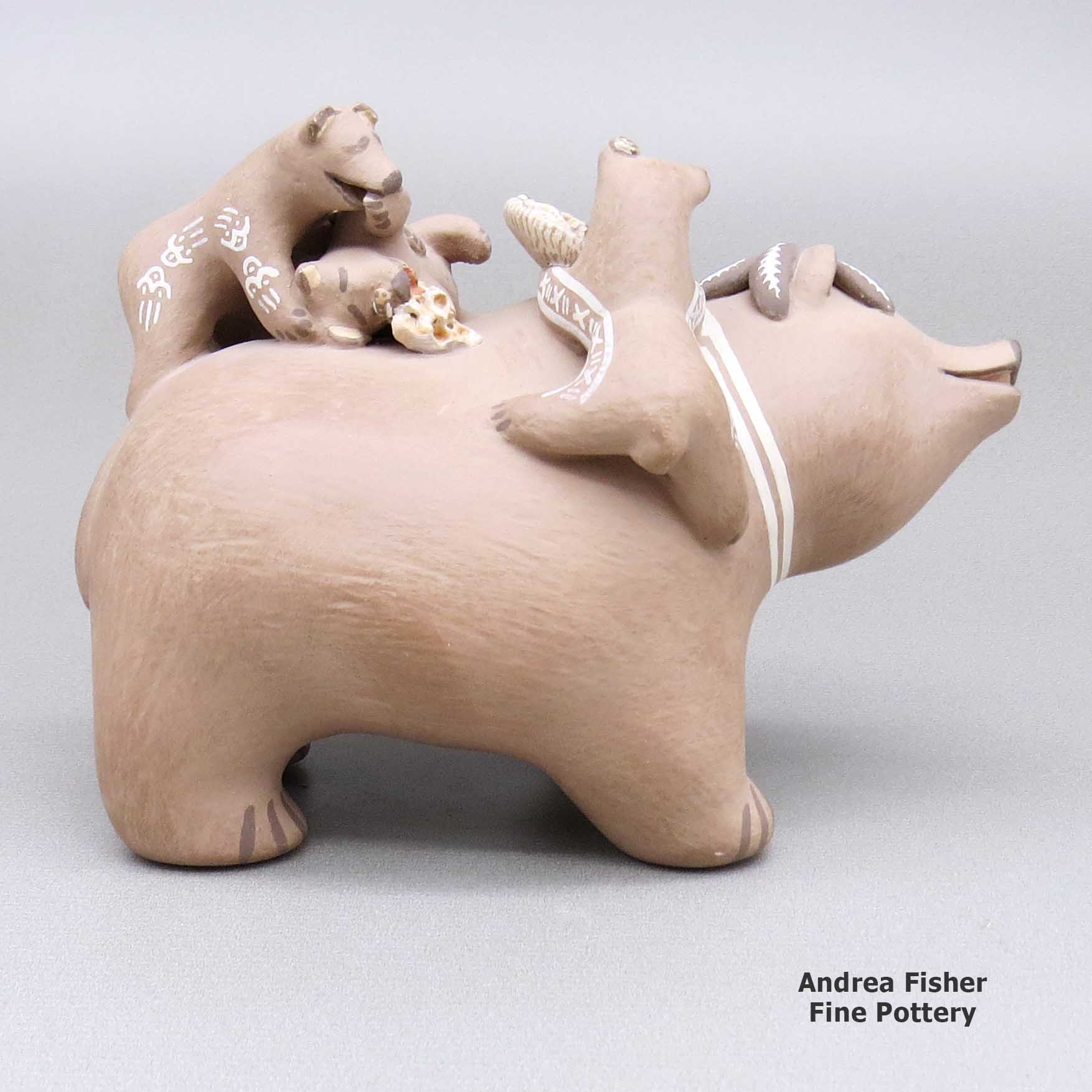

| Dimensions | 2.75 × 4.75 × 3.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Robin Teller Isleta Pueblo New Mexico |

Robin Teller, lcle3b103, Bear storyteller figure

$525.00

A polychrome bear figure with three cubs on its back and decorated with a honeycomb, plate, feather, honeybee and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Teller, Robin

Robin learned the traditional art through watching and working with her mother and by 1991, she was earning ribbons of her own from the Santa Fe Indian Market, Heard Museum and Guild (Phoenix, AZ) and the Eight Northern Pueblo Arts and Crafts Show at Ohkay Owingeh (San Juan Pueblo), near Espanola, NM.

Robin is most known for her Mother Nature storytellers and nativity sets but she also creates jars, bowls, and human and animal figures. Like her mother, Robin prefers to put "sleeping eyes" on her storytellers and nativities.

The mother of two and grandmother of five, Robin says she gets her inspiration from them, as well as from her spiritual journey through life's experiences and her reverence for all of our Creator's blessings.

She integrates those feelings and emotions into her pottery creations, always as part of an individual story or message. Robin's work is always recognizable due to the intricate detailing in her forms and designs. For her, pottery is a mini-canvas.

Robin told us there's a standard of excellence and quality to uphold in relation to the family tradition. That can be seen in the ways in which she expresses her innermost feelings about love, hope and beauty, for the world and for humanity.

Robin has passed her knowledge of the traditional art on to her daughter, Lesley Velardez, who has also blossomed into an award-earning potter.

A Short History of Isleta Pueblo

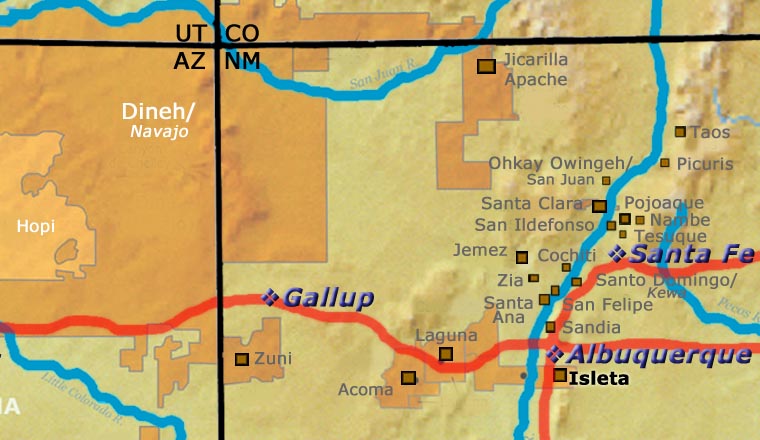

Isleta Pueblo was founded in the 1300s. Archaeologists have put forth various ideas as to where the people came from with some scholars saying they migrated north from Mogollon/Mimbres settlements to the south while others say they migrated southeastward from either Chaco Canyon in the 1100s and 1200s or from the Four Corners area in the 1200s and 1300s. There is every possibility they are an indigenous Tano population that was merged with Aztec migrants coming north from central Mexico and they were never part of the Chacoan world. Their Tiwa language is shared with nearby Sandia Pueblo and a very similar tongue is spoken to the north at Taos and Picuris Pueblos. The two dialects are sometimes referred to as Southern and Northern Tiwa. The Taos people also consider that some of their ancestors migrated north from Aztec lands long ago while others came from the north.

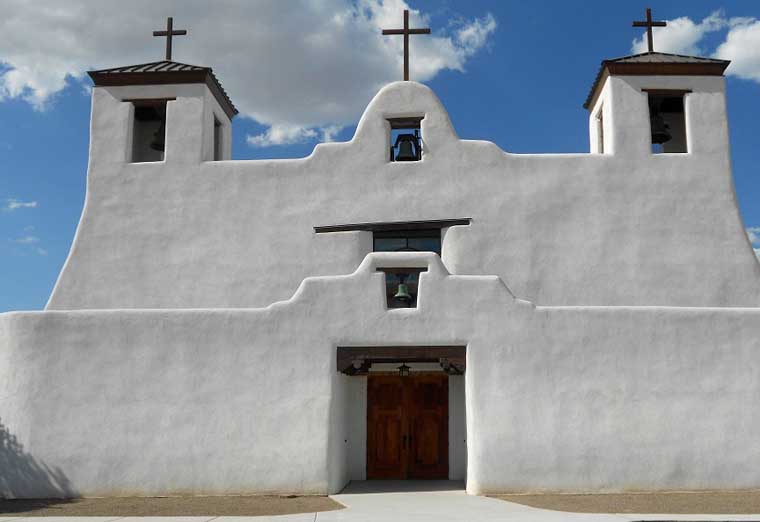

When the Spanish arrived in the area they named the pueblo "Isleta" (meaning: island). The residents were relatively accommodating to the Spanish priests when compared to the reception the same priests got in other areas of Nuevo Mexico (making Isleta something of an "island of safety" for the Spanish in an ocean of hostility). When the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 happened, Isleta either couldn't or wouldn't participate in the rebellion.

When the Spanish governor was evicted from Santa Fe he went to Albuquerque, then to Isleta and gathered his troops. With warriors from the northern pueblos harassing their every move, none of the Spaniards wanted to go back and fight so when they left Isleta and headed south, many Isletans went south to the El Paso area with them. Those who went south were allowed to establish their own pueblo at Ysleta del Sur, a place that at the time was beyond the boundaries of the village of El Paso.

Other Isletans fled to the Hopi settlements in Arizona and returned after the fighting was clearly over, many with Hopi spouses. When the Spanish returned in 1682 they found the Isleta mission church burned and the main structure was being used as a livestock pen. When Don Diego de Vargas came in 1692 with troops intent on reconquering New Mexico, they found the whole village of Isleta empty and burned.

The governor ordered the pueblo be rebuilt and resettled so residents were brought in from Taos and Picuris to the north and from Ysleta del Sur to the south. By 1720 a new, more grandiose mission had been built on the foundations of the first.

Over the next century some dissident members of the Laguna and Acoma Pueblo communities migrated to Isleta. While they were welcomed into the main Isleta pueblo at first, friction developed over the years until in the late 1800s, the small communities of Oraibi and Chicale were established. Most of the newcomers moved to one or the other but some returned to Acoma and Laguna.

For more info:

Pueblo of Isleta at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Isleta official website

About Figures and Figurines

Generally, "Figure" denotes a real or mythic creature, like an owl or human or katsina or Corn Maiden. Whether form or decoration, all Puebloan pottery figures are meant to invoke particular spiritual essences. That's why "effigy" is used almost as often as "figure" to denote these pieces.

Among most Puebloans, the figure of an owl, for example, signifies all the physical and spiritual aspects attributed to the owl. It's a form of prayer to the spirit of "Owl" and the appropriately decorated physical form is meant to make that spirit manifest. However, to the Zuni people an owl is a good omen and to the Tewa people, an owl is a bad omen. Some potters at Santa Clara have made owls anyway, they just shaped and decorated them to reflect that "badness."

That explanation may make more sense in the case of the Corn Maiden as she is a mythic entity whose existence revolves around the most ubiquitous food staple in the Puebloan world: corn (maize). All representations of the Corn Maiden are meant to invoke her benevolence and abundance for their people. Because of her mythical/spiritual nature, different pueblos have slightly different physical forms for her but they all incorporate the basic form of a female human face on an ear of corn.

The potters of Tesuque turned out thousands of muna figures (also known as rain gods)for several decades, until they virutally burned out their pottery tradition. These muna had very specific shapes but were decorated with everything from micaceous slips to incised lines to polychrome geometric designs to poster paints. They were also made purely for domestic American consumption, sometimes delivered by the barrel to be used as prizes and giveaways.

The Storyteller is another figure based on Puebloan tradition: a tribal elder singing the stories of the tribe's oral history to the children. The original was based on the traditional cultural story: a grandfather singing his part of the story in his native language so the children learn both the language and their identity against the backdrop of that history. Shortly, the storyteller form was duplicated in several other pueblos, each pueblo's potters adapting the form to their local situation. In some places, the grandmother became the primary sex of their storytellers. At Jemez, that responsibility was shared between grandmothers and grandfathers. Then some potters in search of new niches in the marketplace branched into making "spirit figure" storytellers, like eagles, ravens, hummingbirds, cats and dogs. Some Zuni potters have made storyteller owls.

Similar to the Storyteller is the Story Time: a set of separate children displayed around a larger central singing figure.

The Nativity set (also known as nacimiento) is a set of figures based on the intersection of Puebloan mythologies and stories they heard from Christian missionaries. Those potters who make them also tend to favor dress, shapes and designs that reflect their own heritage(s). The first few nativities made at Tesuque Pueblo were decorated with Spanish colonial costumes but that soon changed and every nativity made since has a distinct blend of Native American and Christian, with no other reference to colonialism. The "Singing Angel" (a single standing figure with outstretched wings and hands clasped together in prayer) and "Flight to Egypt" (usually depicting Mary with a baby Jesus on the back of a donkey and a standing Joseph nearby holding the rein) are similar mixes of tribal and Christian figures. The miniature nativities made by Santa Clara/Dineh artist Linda Askan clearly show Dineh religious influence in the headresses worn by Joseph, the angel and the three wise men. At the same time, the Dineh Folk Art nativities made by Jonathan Chee are based on the realities of daily Dineh life: the three wise men wear wide-brim hats and blue jeans, and bring gifts of salt and 50-pound bags of flour.

Pueblo and Dineh artists also make a full zoo of domesticated, farm and wild animal figures: horses, donkeys, cows, chickens, pigs, sheep, turkeys, giraffes, elephants, dogs, cats, mermaids, women-dressed-up-and-taking-selfies and cowboys among them.

About the Storyteller

Historically, clay figures have been present in the Pueblo pottery tradition for more than a thousand years. However, figures and effigies were denounced as "works of the devil" by the Spanish missionaries in New Mexico between 1540 and 1820. Before and after that time the art of making figurative sculpture flourished, especially at Cochiti Pueblo. At Cochiti, the forms of animals, birds, caricatures of outsiders and, more recently, images of mothers and grandfathers telling stories and singing to children have multiplied.

The "storyteller" is an important role in the tribes as parents are often too busy working and raising kids to pass on their tribal histories. The Native American people did not develop a written language to record anything for posterity. Some tribes still refuse to create one. The closest thing they had to a written language was recorded on pottery and textiles, in the form of painted designs that decorate that pottery and textiles.

The storyteller's role was to preserve and retell and pass down the oral history of his people in their native language. In most tribes that role was fulfilled by elder men.

The first recorded storyteller figure was created in 1964 by Cochiti Pueblo potter Helen Cordero in memory of her grandfather, Santiago Quintana. She gathered her clay from a secret sacred place on the lands of her pueblo. Then she hand-coiled, hand painted and fired that first storyteller figure the traditional way: in the ground. Helen never used any molds or kilns to make her pottery.

Helen's creation immediately struck a chord throughout all the pueblos as the storyteller is a figure central to all their societies. Most tribes also have the figure of the Singing Maiden in their pantheon and in many cases, the mix of Singing Maiden and Storyteller has blurred some lines in the pottery world.

Today, as many as three hundred potters in thirteen pueblos have created storytellers. Their storytellers are not only men and women but also Santa’s, mudheads, koshares, bears, owls, eagles and other animals, sometimes encumbered with children numbering more than one hundred! Each potter has also customized their storyteller figures to more closely reflect the styles and dress of their own tribes, often even of their own clans.

Teller Family Tree - Isleta Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Marcellina Jojola (c. 1860s-)

- Emily Lente Carpio (c. 1880s-)

- Felecita Jojola (c. 1900s-) & Rudy Jojola

- Stella Teller (1929-) and Louis Teller

- Chris Teller Lucero (1956-)

- Marie (Robin) Teller Velardez (1954-) and Ray Velardez

- Lesley Teller Velardez (1973-)

- Mona Blythe Teller (1960-)

- Christopher Teller

- Nicol Teller Blythe (1978-)

- Lynette Teller (1963-)

- Stella Teller (1929-) and Louis Teller

- Felecita Jojola (c. 1900s-) & Rudy Jojola