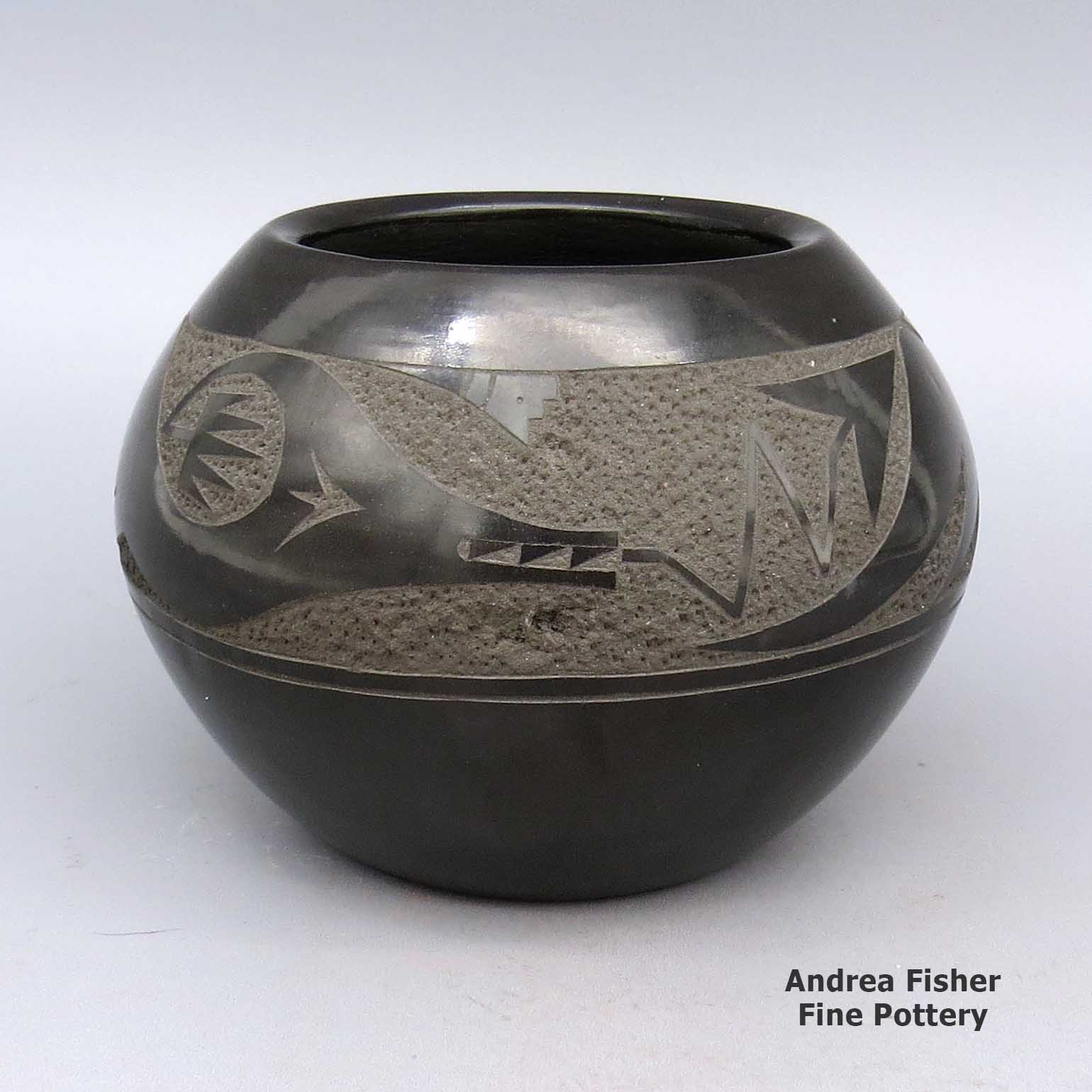

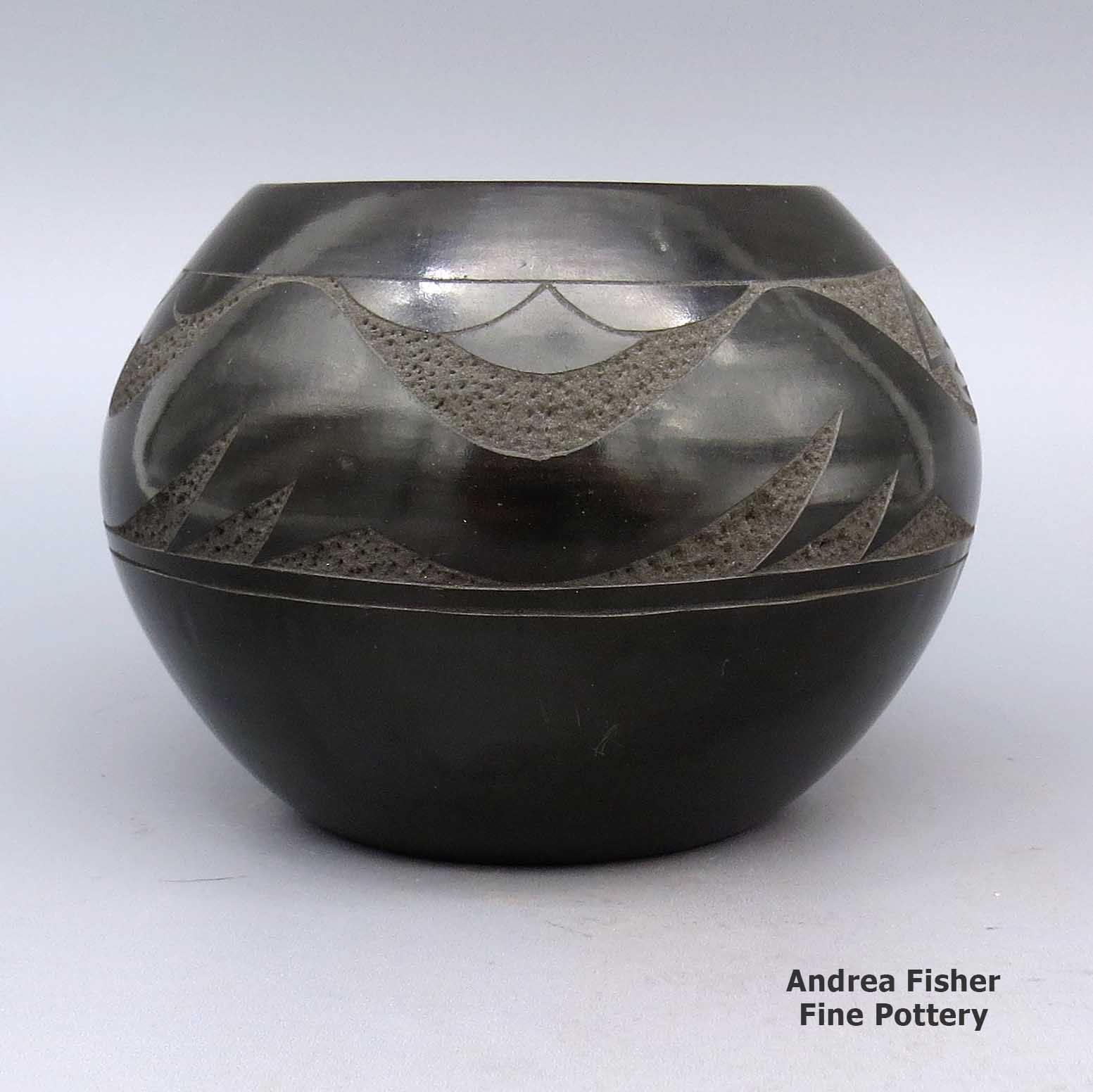

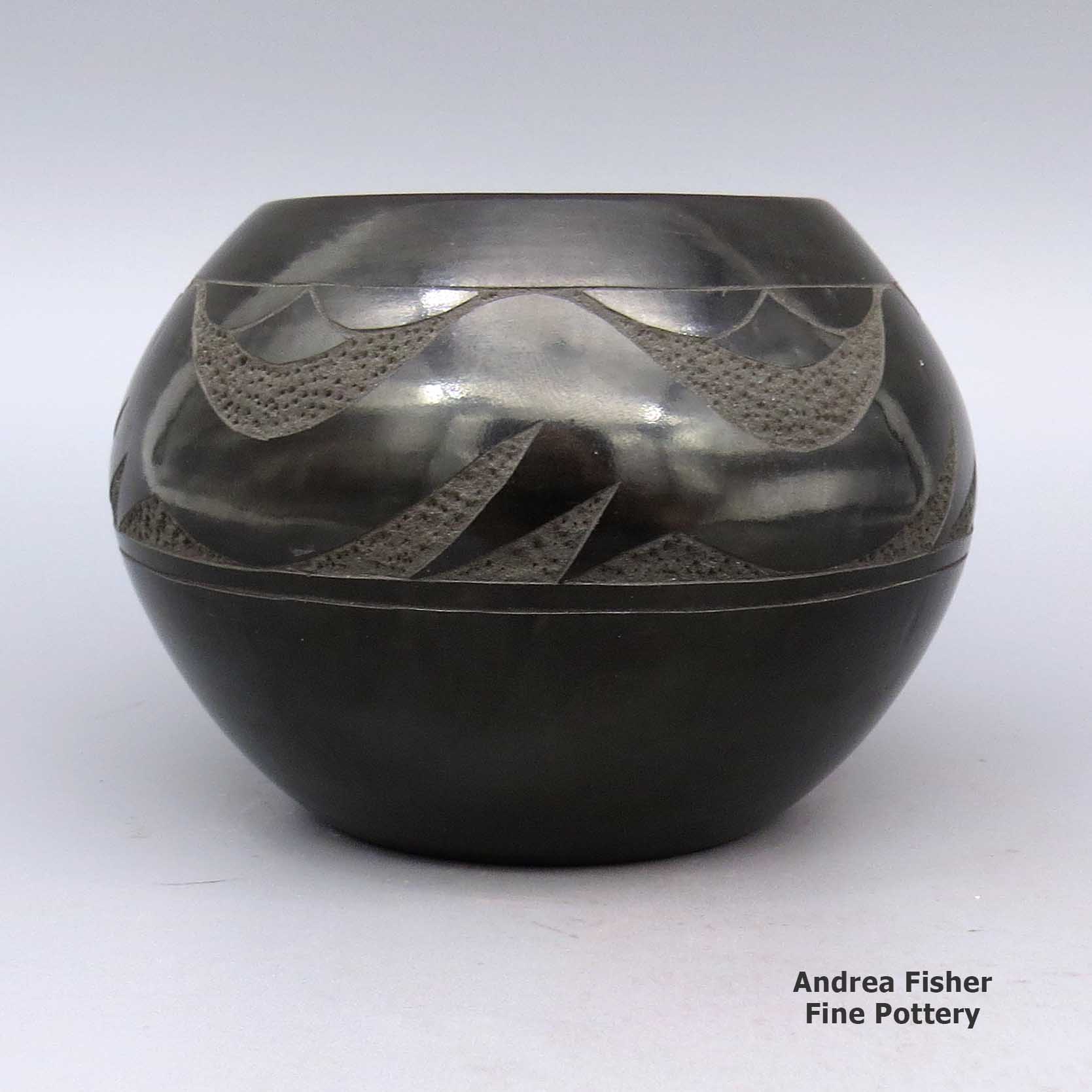

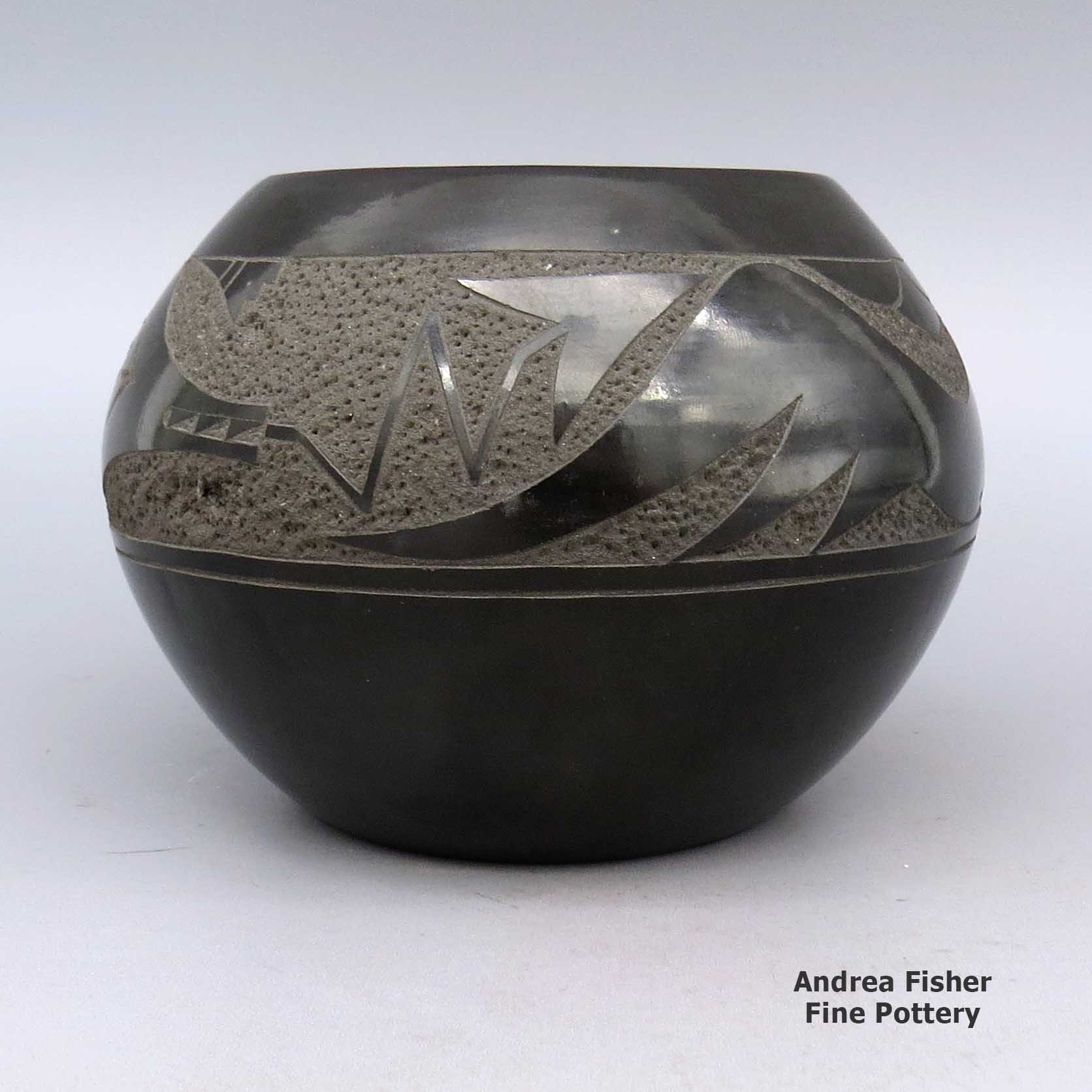

| Dimensions | 4.5 × 4.5 × 5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Date Born | 2004 |

| Signature | Rose Lovato San Ildefonso Pueblo |

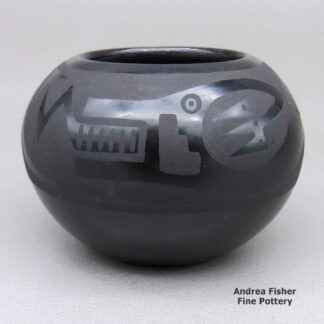

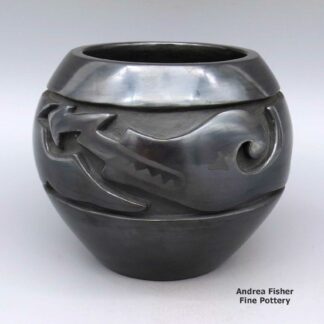

Rose Lovato-Fragua, cjsi2k069, Bowl with avanyu design

$375.00

A black bowl with a sgraffito plumed avanyu and geometric design around the body

In stock

Brand

Lovato-Fragua, Rose

Rose married into the Fragua family of Jemez Pueblo. She learned her pottery making skills, however, from her mother and from her illustrious uncle, Juan Tafoya.

Rose has shown her works at the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Arts and Crafts Show in Espanola but with a pair of active twins in elementary school back then, she didn't have a lot of time to prepare for those shows.

Rose says she gets her inspiration from her Uncle Juan. Her favorite shape to work with is the bowl and her favorite designs revolve around the avanyu (the Tewa water serpent). The world will probably see more work from this talented traditional artist as her children grow older and she discovers the need for more time to de-stress...

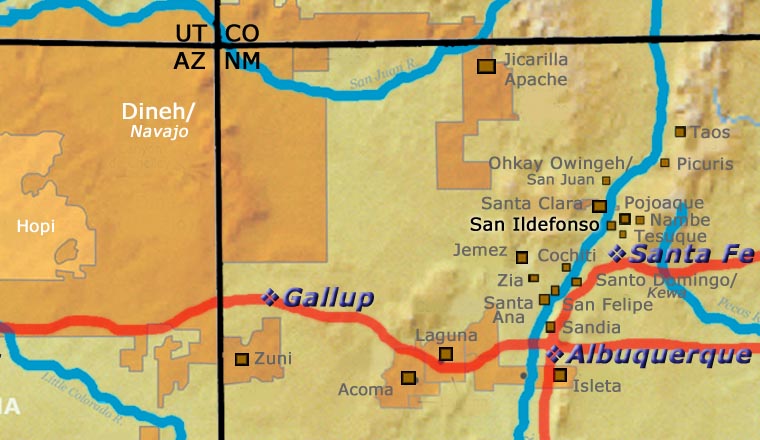

A Short History of San Ildefonso Pueblo

San Ildefonso Pueblo is located about twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico, mostly on the eastern bank of the Rio Grande. Although their ancestry has been traced as far back as abandoned pueblos in the Mesa Verde area in southwestern Colorado, the most recent ancestral home of the people of San Ildefonso is in the area of Bandelier National Monument, the prehistoric village of Tsankawi in particular. The area of Tsankawi abuts today's reservation on its northwest side.

The San Ildefonso name was given to the village in 1617 when a mission church was established. Before then the village was called Powhoge, "where the water cuts through" (in Tewa). The village is at the northern end of the deep and narrow White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. Today's pueblo was established as long ago as the 1300s and when the Spanish arrived in 1540 they estimated the village population at about 2,000.

That first village mission was destroyed during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Don Diego de Vargas returned to reclaim the San Ildefonso area in 1694, he found virtually the entire tribe on top of nearby Black Mesa, along with almost all of the Northern Tewas from the various pueblos in Tewa Basin. After an extended siege, the Tewas and the Spanish negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their villages. However, the next 250 years were not good for any of them.

The Spanish swine flu pandemic of 1918 reduced San Ildefonso's population to about 90. The tribe's population has increased to more than 600 today but the only economic activity available for most on the pueblo involves the creation of art in one form or another. The only other jobs are off-pueblo. San Ildefonso's population is small compared to neighboring Santa Clara Pueblo, but the pueblo maintains its own religious traditions and ceremonial feast days.

Photo is in the public domain

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About the Avanyu

The avanyu is a mythical water creature likened to the feathered and plumed serpents of Mesoamerica. The design is primarily part of the design palette of Tewa potters from the Tewa Basin, and even there it varies by pueblo and artist. Wherever the artist is, the avanyu design generally represents the spirit of water rushing through a village after a downpour. The avanyu is also seen as the Keeper of Springs and Guardian of Water. The image is a prayer for rain with the realization of what a downpour can do when it falls on the hard soil of the arid and semi-arid Southwestern deserts.

Artists from San Ildefonso Pueblo generally use an avanyu design with a three-plumed head while Santa Clara Pueblo potters generally use an avanyu with three feathers hanging off the head. The avanyu always has a forked tongue, signifying the lightning bolts that herald its arrival. Some have simplified the design to one feather or plume while others have stylized the design and almost made it cubic or Oriental in design and layout.

Hopi-Tewa potters generally use a somewhat similar Hopi version of a flying, feathered serpent named kwataka. The Zuni version is Kolowisi, although it has been determined that the power of Kolowisi is too much for anyone who is not of Zuni descent so depictions of it have gotten almost as rare as depictions of kwataka.