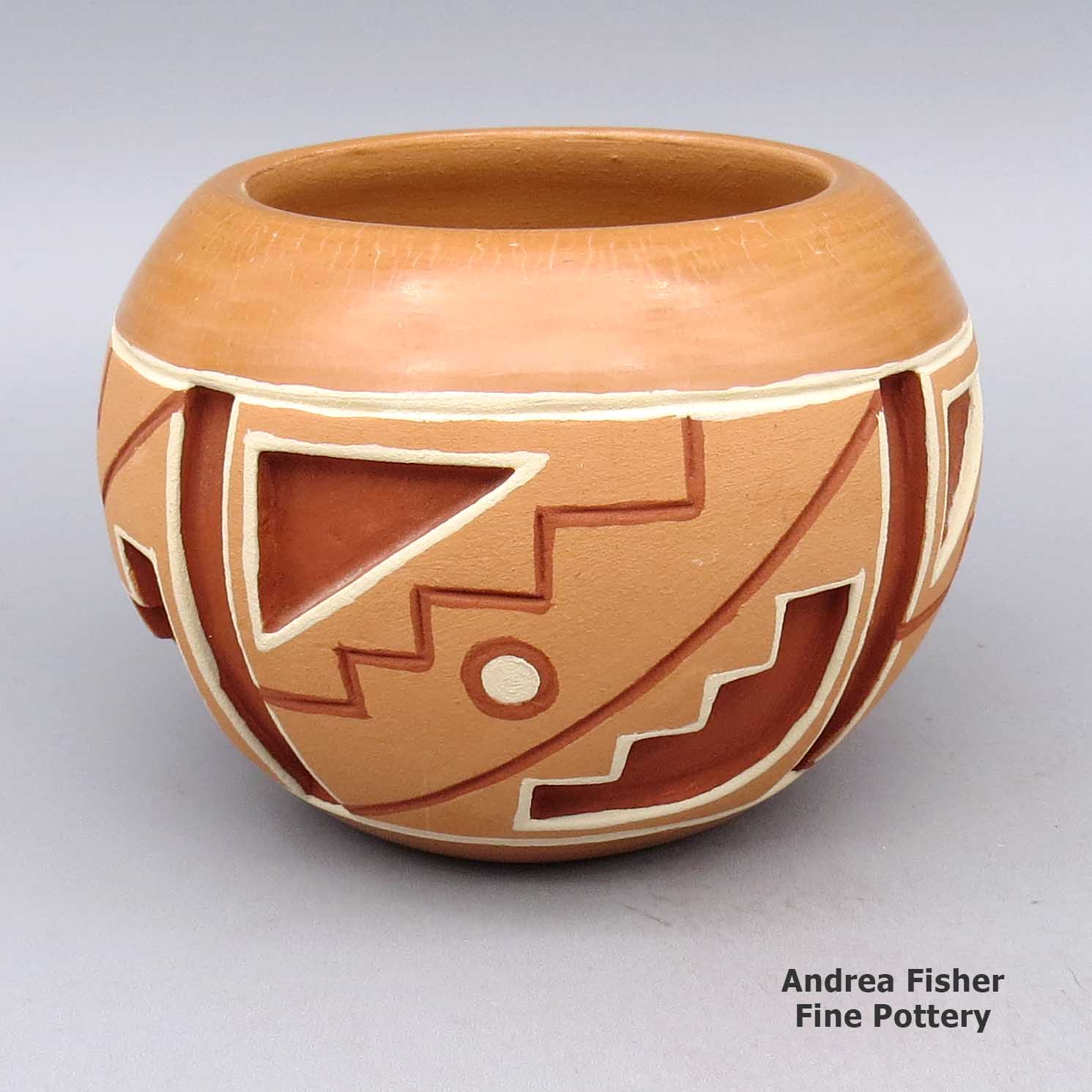

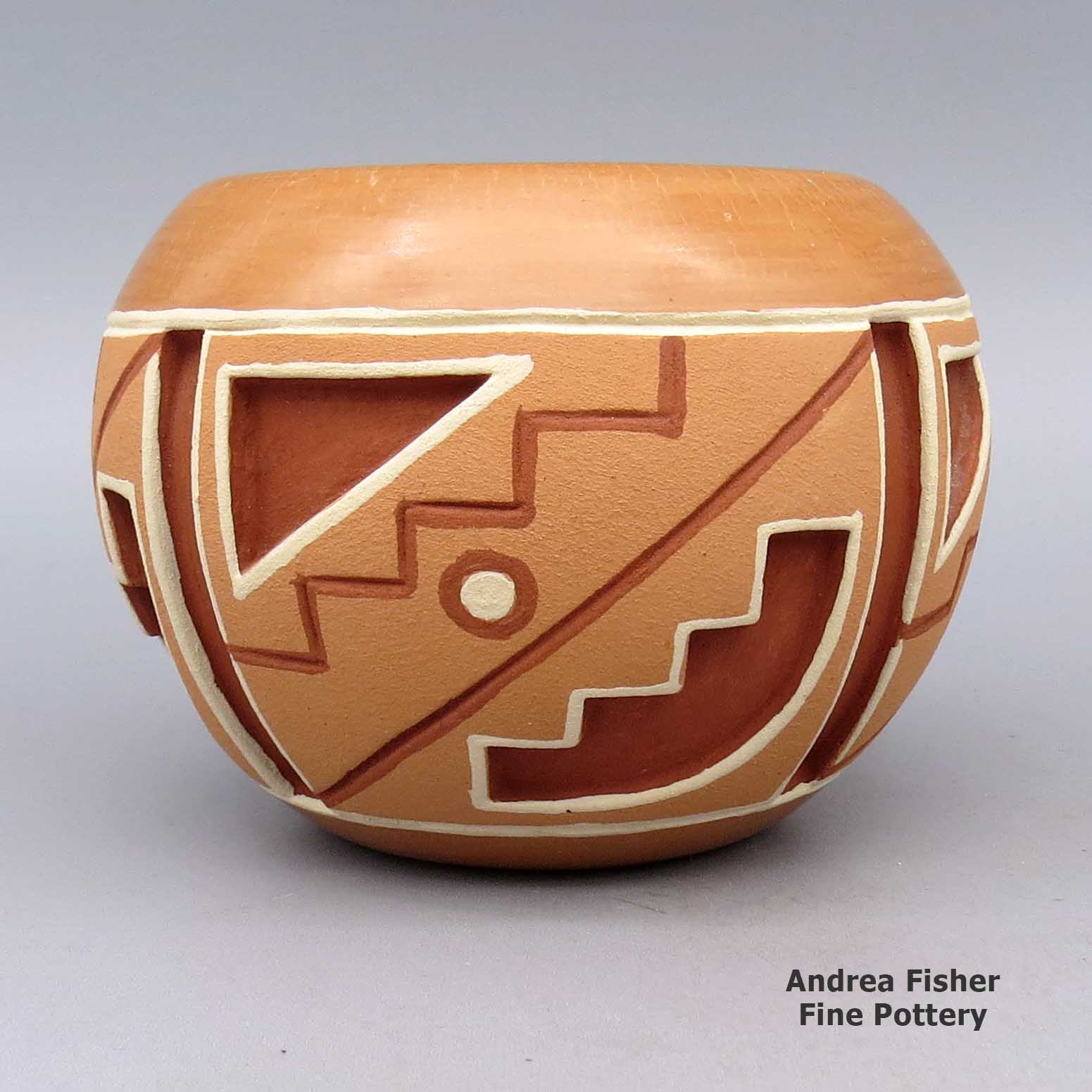

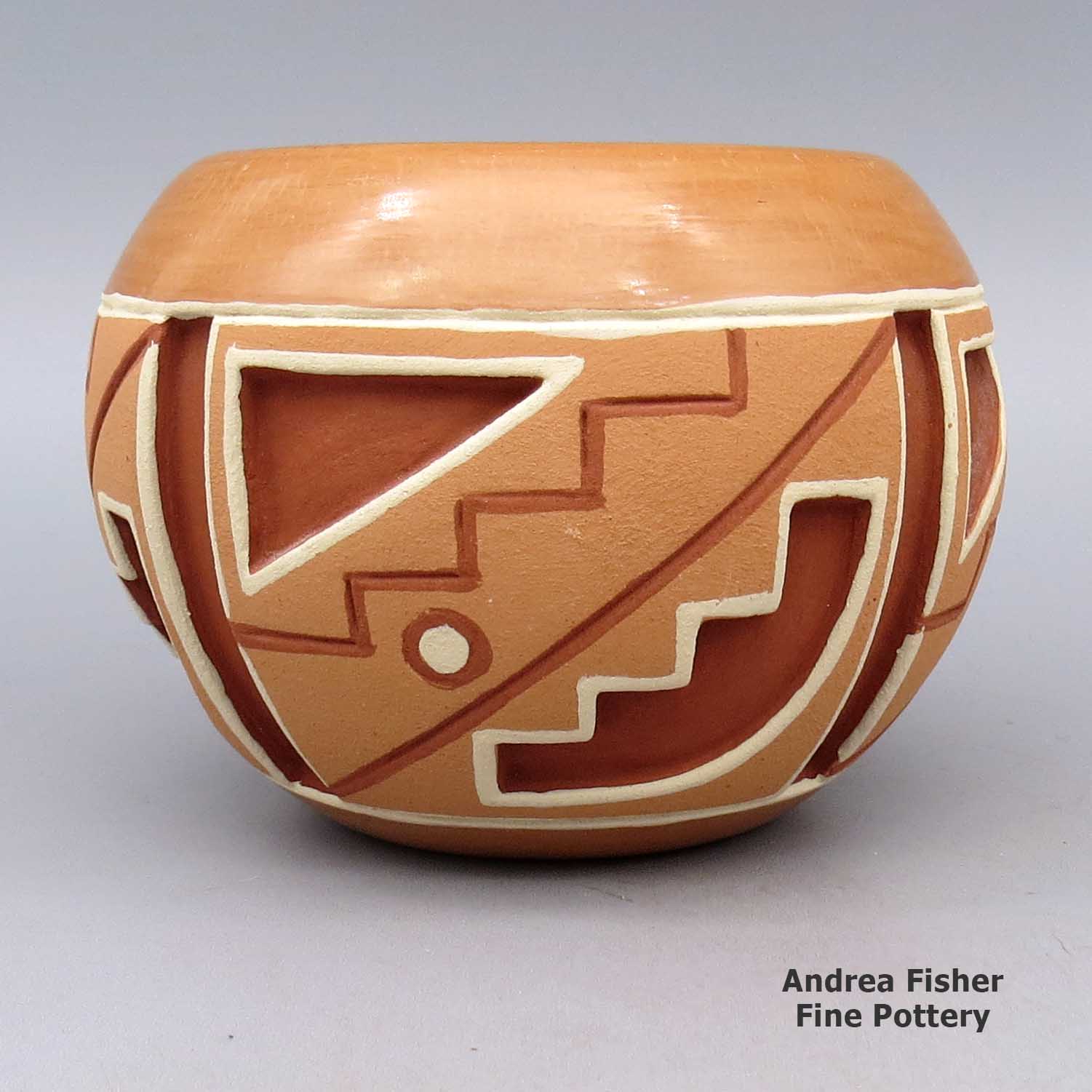

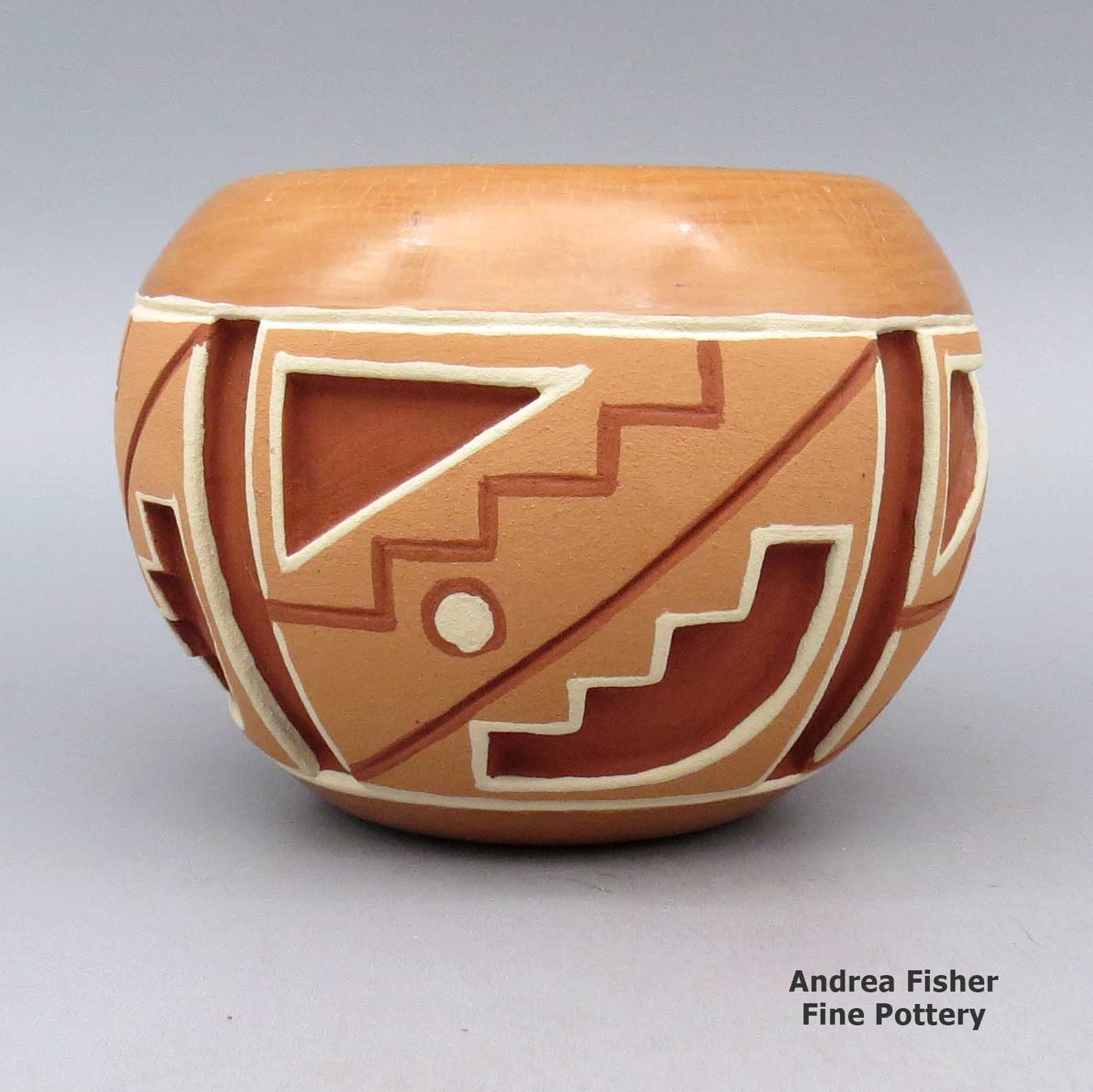

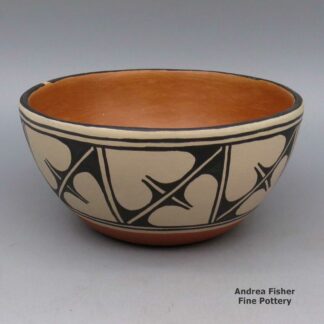

| Dimensions | 4.5 × 4.5 × 3.25 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, rubbing on bottom |

| Signature | Rosita De Herrera San Juan Pueblo, N.M. |

Rosita de Herrera, cmsj2l087, Polychrome bowl with four panel geometric design

$295.00

A polychrome bowl decorated with a carved-and-painted four-panel geometric design, in the Potsuwi’i fashion

In stock

- Product Info

- About the Artist

- Home Village

- Design Source

- About the Shape

- About the Design

- Family Tree

Brand

de Herrera, Rosita

Some ancient Tewa pottery had been found on Ohkay Owingeh land and it was dated by archaeologists to have been made just prior to the arrival of the Spanish in New Mexico. They based their definition on that pottery and named it Potsuwi'i, after the ancient pueblo where it was found.

They settled on decorating redware pots with a matte design band that featured the old incised designs (that are similar to a lot of rock art found across the Southwest). Rosita and her sister, Dominguita Sisneros, grew up learning to make that style of pottery from their mother. Rosita's son, Norman de Herrera, grew up learning how to make pottery the same way, from Rosita.

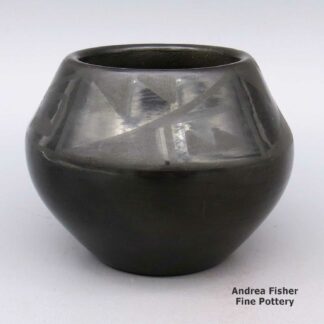

Rosita was active in the marketplace by the early 1970s. She mostly made incised polychrome buff-on-red bowls in the Potsuwi'i style and incised blackware bowls in a more recent (colonial) Ohkay Owingeh style.

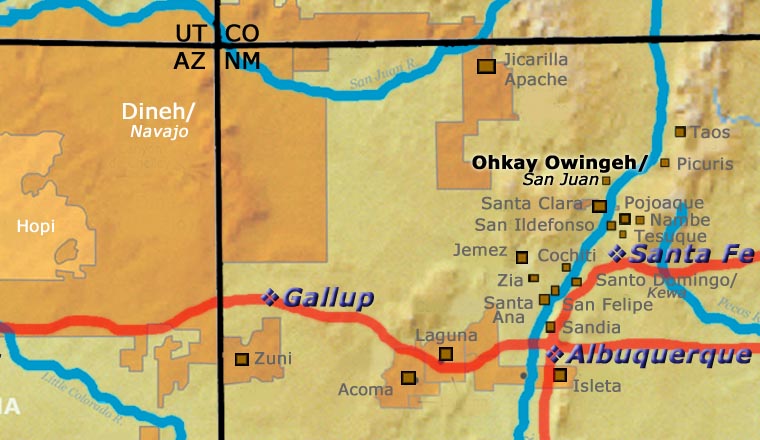

A Short History of Ohkay Owingeh

In 2005 San Juan Pueblo officially changed its name back to its original name (before the Spanish arrived): Ohkay Owingeh (meaning: Place of the strong people). The pueblo was founded after 1200 CE during the time of the great Southwest drought and migrations. The people speak Tewa and may have come to the Rio Grande area from southwestern Colorado or from the San Luis Valley in central Colorado.

Spanish conquistador Don Juan de Oñate took control of the pueblo in 1598, renaming it San Juan de los Caballeros (after his patron saint, John the Baptist). He established the first Spanish capitol of Nuevo Mexico across the Rio Grande in an area he named San Gabriel. In 1608, the capitol was moved south to an uninhabited area that became the Santa Fe we know today.

After 80 years of progressively deteriorating living conditions under Spanish rule, the people of Ohkay Owingeh participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 (one of the revolt's ringleaders, Popé, was a spiritual leader at Ohkay Owingeh) and helped to expel the Spanish from Nuevo Mexico for 12 years. However, when the Spanish returned in 1692 that tribal unity had fallen apart and the individual pueblos were relatively easy for the Spanish to reconquer.

Today, Ohkay Owingeh is the largest Tewa-speaking pueblo (in population and land) but few of the younger generations are interested in carrying on with many of the tribe's traditional arts and crafts (such as the making of pottery). The pueblo is home to the Eight Northern Indian Pueblos Council, the Oke-Oweenge Arts Cooperative, the San Juan Lakes Recreation Area and the Ohkay Casino & Resort. The tribe's Tsay Corporation is one of northern New Mexico's largest private employers.

For more info:

Ohkay Owingeh at Wikipedia

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

About the Potsuwi'i Style

In the 1920s and 1930s, there were movements in nearly all the pueblos to revive their ancient arts and crafts, the things that helped to shape their history and make them who they are. At Ohkay Owingeh a group of eight women got together and first planned to go into embroidery. Then came word of an old pueblo found where someone was digging a hole for the basement of a house. They started turning up artifacts and stopped their work, waiting for the archaeologists to arrive and do their thing.

There was a significant amount of ancient pottery found in and around the old pueblo. It had very distinctive shapes and designs. It was dated to have been made around 1450-1500 CE, therefore before the Spanish arrived in the area and exerted their considerable influence on things. This group of women worked with those old pots and eventually came up with a definition of Potsuwi'i pottery, naming it for the village where it was found. Potsuwi'i pottery became the standard for traditional Ohkay Owingeh pottery.

Their definition was basically "decorative zones of geometric fine lines with selected areas of polished red slip." Some potters painted micaceous slip into the fine line grooves and some carved, etched and painted other designs on their pots.

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

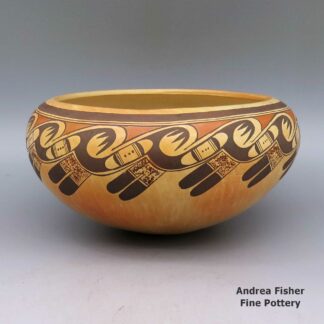

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.

Tomasita Reyes Montoya Family Tree - San Juan Pueblo/Ohkay Owingeh

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Tomasita Reyes Montoya (1899-1978) and Juan Reyes Montoya

- Dominguita Sisneros (1942-) and Juan Sisneros

- Jennifer Naranjo and Alfred E. Naranjo (Santa Clara)

- Alfred J. Naranjo

- Jeannette Teba and Steven Teba Sr.

- Steven Teba Jr.

- Veronica Teba

- Jennifer Naranjo and Alfred E. Naranjo (Santa Clara)

- Rosita de Herrera (1940-)