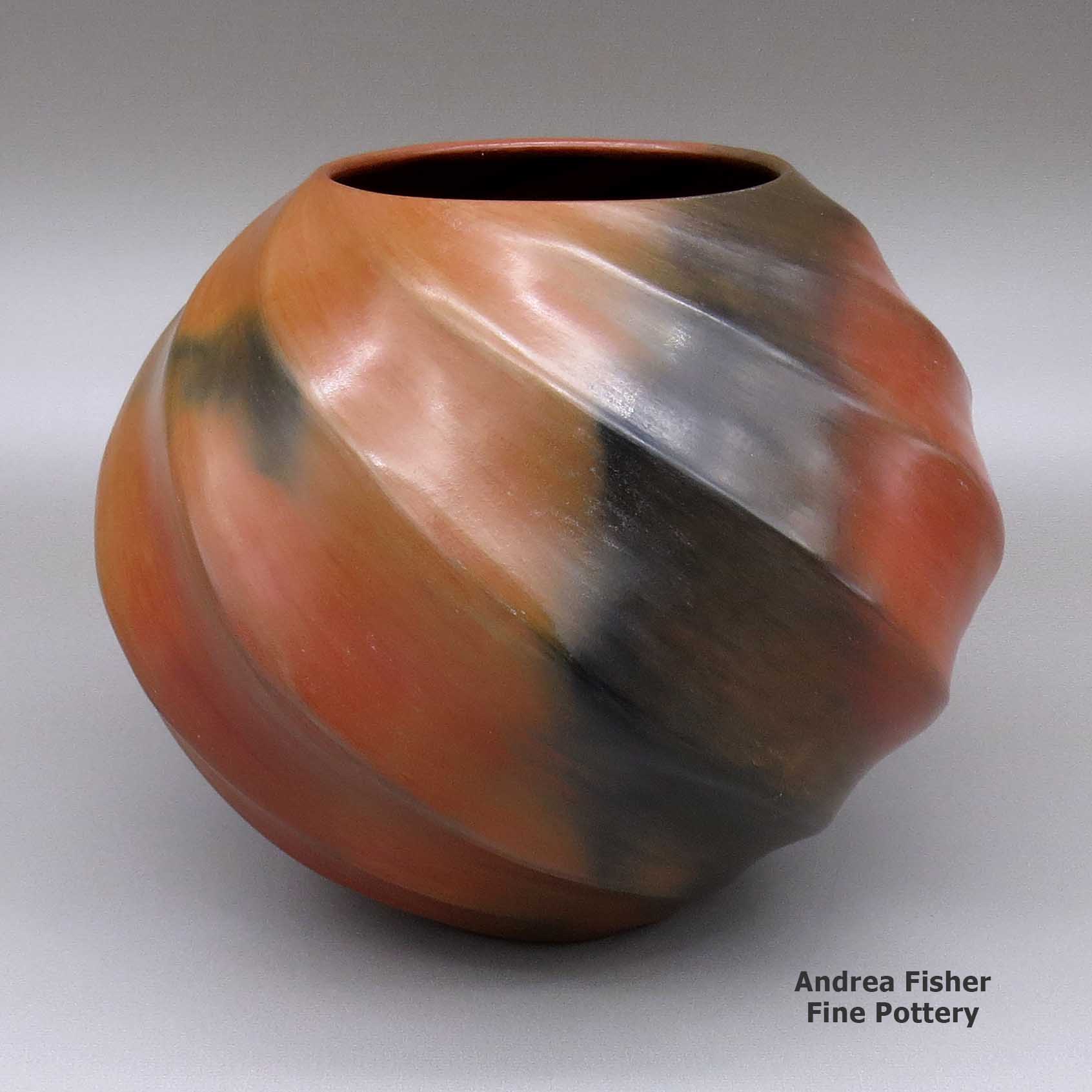

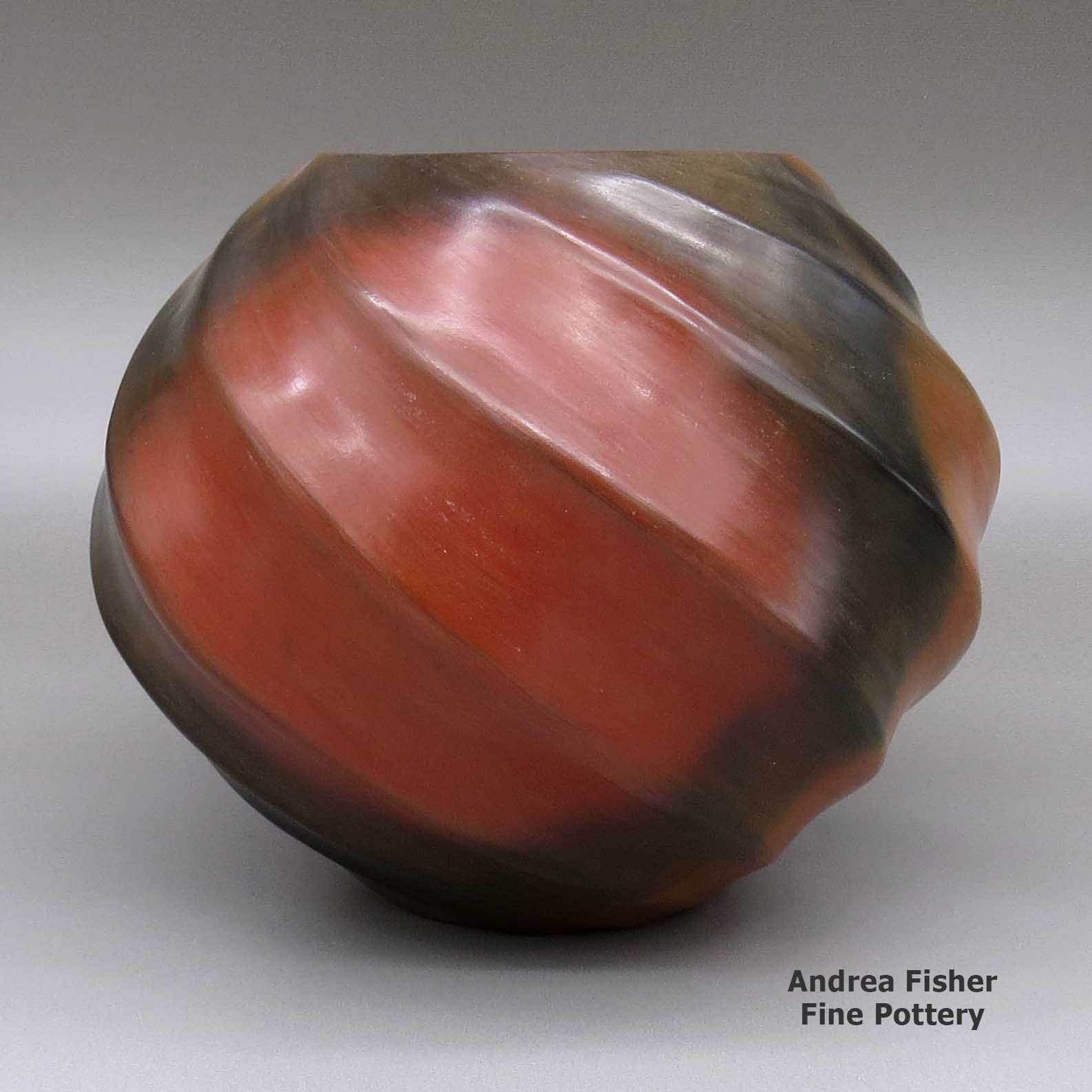

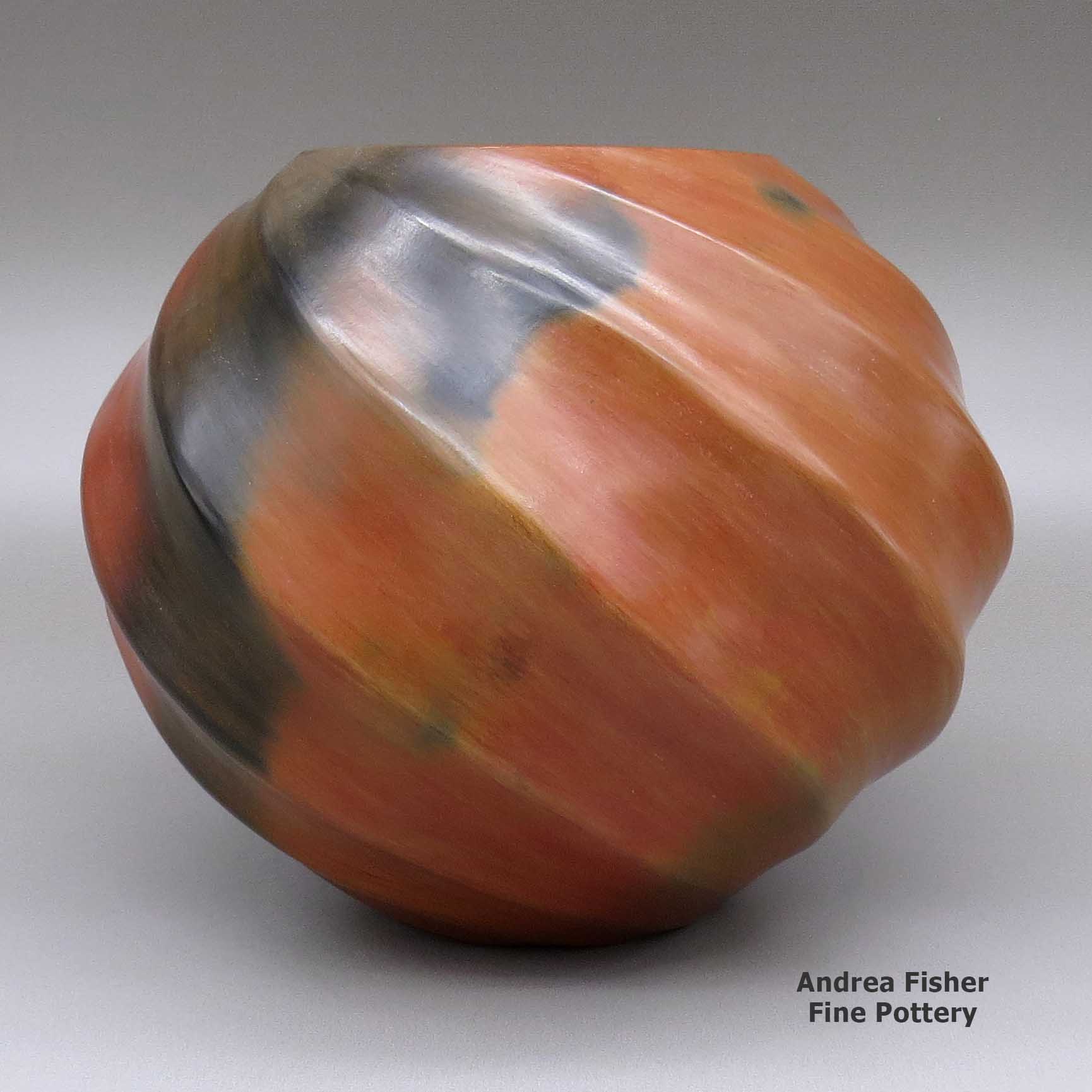

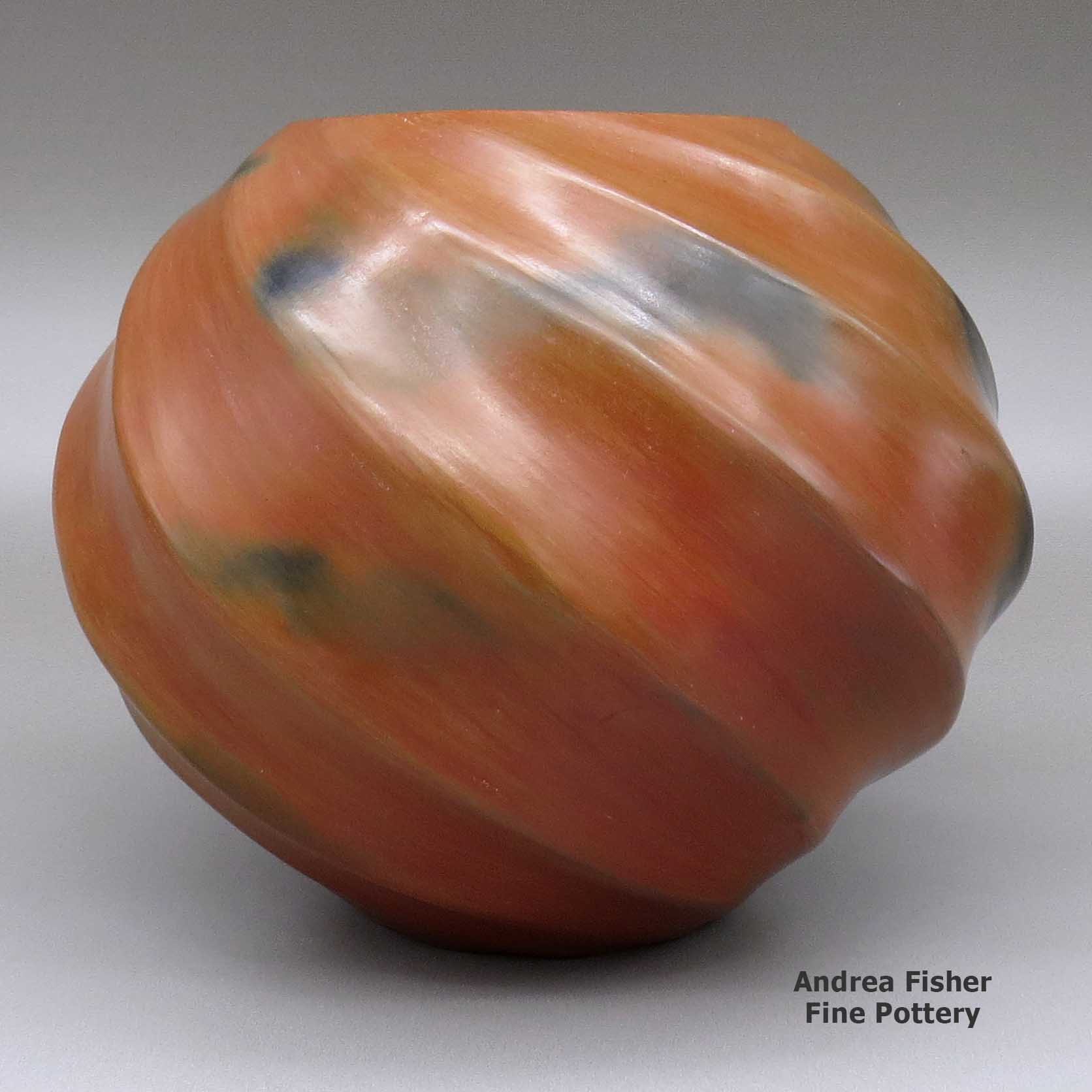

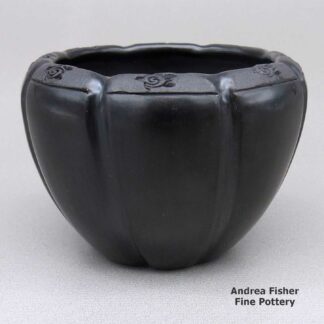

| Dimensions | 9 × 9 × 8 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, rubbing on bottom |

| Signature | Sam Dine |

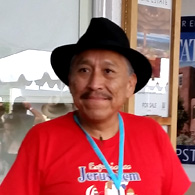

Samuel Manymules, rwnv2b250, Melon jar with ten ribs and fire clouds

$2,500.00

A red swirl melon jar with ten ribs and fire clouds

In stock

Brand

Manymules, Samuel

"I spend most of my days envisioning the shapes, planning how to make a vision a reality, and imagining how the completed pot will look."

"I spend most of my days envisioning the shapes, planning how to make a vision a reality, and imagining how the completed pot will look."Samuel Manymules was born into the Bitterwater Clan of the Red Horse Nakai Navajo Clan in August, 1963. For many years he says he only did what he needed to to get by. Jobs that still stick out in his mind are jewelry making, driving a tow truck and working at an auto dealership trying to make ends meet.

Then he started finding potsherds on the ground in the area around where he lived. They intrigued him enough that he taught himself how to make pottery the traditional way.

He says he got his inspiration in the early days by looking at the pottery of Christine McHorse and Joseph Lonewolf.

After ten years of dabbling with clay, he perfected a thin wall version of Navajo pottery and with his typical high fire practice, he's since elevated Navajo pottery to a whole new level.

Samuel tells us he builds his pots in his mind before he ever puts his hands in the clay. "I spend most of my days envisioning the shapes, planning how to make a vision a reality, and imagining how the completed pot will look," he told us.

In keeping with Navajo tradition, Samuel neither paints nor carves his pieces. He knows his clay so well he pushes and presses it into the forms he wants, creating the architectural angles of a master and decorating without actually decorating. Then he leaves the making of color variations to the firing process where he says the Hand of the Creator makes its mark.

Samuel has a long list of accomplishments and awards in the pottery world. The basics of the list cover most of a printed page as he has won many prominent awards from some of the most distinguished juried competitions in the southwestern United States.

Some Awards Samuel has earned

- 2019 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 501 - Pitch Finish, any form: Second Place

- 2018 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 501 - Pitch Finish, any form: First Place

- 2018 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, including ribbed, native clay, hand built, fired out-of-doors: Second Place. Awarded for a Four-Sided Swirled Water Jar

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 501 - Pitch Finish, any form: First Place

- 2017 Santa Fe Indian Market: Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional Unpainted Pottery, Category 504 - Melon bowls and melon jars, formed or carved: Second Place

- 2017 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Unpainted, Including Ribbed Native Clay, Hand Built, Fired Out-of-Doors: Second Place. Awarded for Artwork: "Kiva Entry"

- 2015 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-traditional design or form with native materials: First Place

- 2014 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted including ribbed: Second Place. Awarded for Melon Swirl Water Jar

- 2013 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, painted, including ribbed: First Place

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted including ribbed: First Place

- 2012 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Award - Martha Streuver. Awarded for artwork: Water Jar

- 2011 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted including ribbed: First Place

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional, native Clay, hand built, carved: Second Place

- 2010 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand built, unpainted including ribbed: First Place

- 2009 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand-built, unpainted: First Place

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division E - Non-traditional design or form with Native materials: Second Place

- 2008 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market: Judge's Choice Award - Marcus Monenerkit

- 2007 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional, native clay, hand-built, unpainted: Second Place

- 2006 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division C - Traditional - Native clay/hand built/carved/ribbed/incised: First Place

- 2005 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery Division B - Traditional/native clay/hand-built (unpainted): Honorable Mention

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style all forms: Second Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division A - Traditional unpainted pottery, Category 801 - Navajo style all forms: Third Place

- 2004 Santa Fe Indian Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional undecorated, Category 901: Third Place

- 2004 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery: Best of Classification

- 2004 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional/native clay/hand-built (unpainted): Best of Division

- 2003 Heard Museum Guild Indian Fair & Market, Classification II - Pottery, Division B - Traditional/native clay/hand-built (unpainted): Honorable Mention

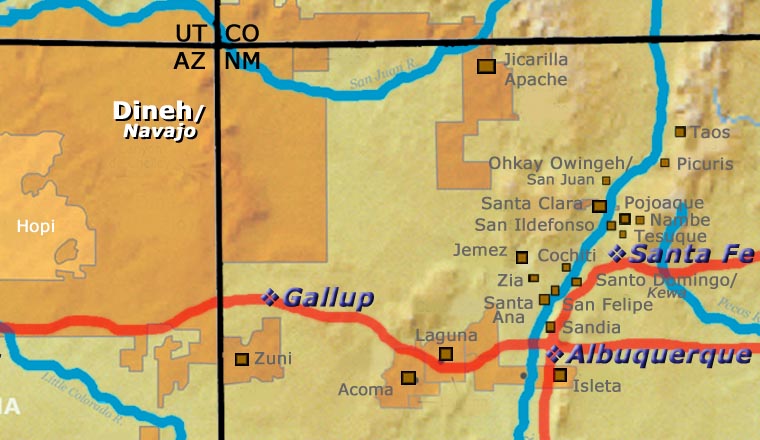

About the Dineh

Historical and archaeological evidence points to the Dineh entering the Southwest around 1400 AD. Their oral history still contains stories of that migration as the journey began in eastern Alaska and northwestern Canada centuries after their ancestors made the journey across the Bering Land Bridge from central Asia about 10,000 years ago. They were primarily hunter-gatherers until they came into contact with the Pueblo peoples and learned the basics of survival in this drier climate. Dineh oral history points to a long relationship between the Dineh and the Ancestral Puebloans as they learned from and traded with each other.

When the Spanish first arrived, the Dineh occupied much of the area between the San Francisco Peaks (in Arizona), Hesperus Mountain and Blanca Peak (in Colorado) and Mount Taylor (in New Mexico). Spanish records indicate they traded bison meat, hides and stone to the Puebloans in exchange for maize and woven cotton goods. It was the Spanish who brought sheep to the New World and the Dineh took to sheep-herding quickly with sheep becoming a form of currency and sign of wealth.

When the Americans arrived in 1846, things began to change. The first fifteen years were marked by broken treaties and increasing raids and animosities on both sides. Finally, Brigadier General James H. Carleton ordered Colonel Kit Carson to round up the Dineh and transport them to Bosque Redondo in eastern New Mexico for internment. Carson succeeded only by engaging in a scorched earth campaign in which his troops swept through Dineh country killing anyone carrying a weapon and destroying any crops, livestock and dwellings they found. Facing starvation and death, the last band of Dineh surrendered at Canyon de Chelly.

Carson's campaign then led straight into "the Long Walk" to Bosque Redondo, a 300-mile trek during which at least 10% of the people died along the way. At Bosque Redondo they discovered the government had not allocated an adequate supply of water, livestock, provisions or firewood to support the 4,000-5,000 Dineh interned there. The Army also did little to protect the Dineh from raids by other tribes or by Anglo citizens. The failure was such that the Federal government and the Dineh negotiated a treaty that allowed the people to return to a reservation that was only a shadow of their former territory little more than a couple years after they had left. However, succeeding years have seen additions to the reservation until today it is the largest Native American Reservation in the 48 contiguous states.

Large deposits of uranium were discovered on the Dineh Nation after World War II but the mining that followed ignored basic environmental protection for the workers, waterways and land. The Dineh have made claims of high rates of cancer and lung disease from the environmental contamination but the Federal government has yet to offer comprehensive compensation.

The location of the Dineh Nation

For more info:

Navajo Nation at Wikipedia

Diné people at Wikipedia

Navajo Nation Government official website

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Dineh Pottery

As a nomadic people, pottery didn't make much sense to the Dineh as they made the journey south from the northwestern corner of North America. When they came up against the Ancestral Puebloans they settled into a more sedentary lifestyle. The puebloans taught them much about how to survive in this climate on this landscape. That included the making of pottery for utilitarian purposes. That suited the Dineh religious authorities and as more and more Anglo settlers came into the area, they developed a business selling utilitarian wares to them. That essentially ended when the United States came into ownership of the land and American traders arrived with their relatively inexpensive and long-lasting enameled and cast iron cookware. Then pottery production scaled back to just ceremonial pieces being made.

Rose Williams learned how to make pottery from her aunt, Grace Barlow. Rose learned how to make basic brown pottery in utilitarian shapes. She only allowed herself the occasional rope biyo' for decoration, relying more on how she stacked her wood in the firing to make the fire clouds she wanted. Rose liked to make large brown jars which were often used to make drums. Living to be 99 years old and making pottery almost until she passed, Rose taught many people how to make pottery.

Grace Barlow also taught her granddaughter, Betty Manygoats. Betty in turn, taught all her children how to make pottery. Only Elizabeth has made a living at it.

Other modern potters on the reservation have usually learned how to make pottery the traditional way in the classrooms at the Institute for American Indian Arts.

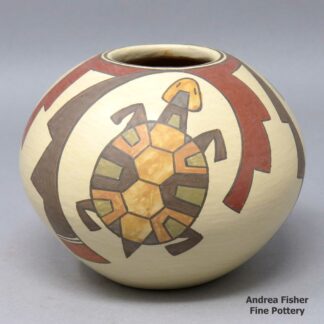

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About the Melon Jar

The lives of the various centuries-old pueblo cultures have been based on the cycles of agriculture, specifically the growing and harvesting cycles of the "three sisters": maize, squash and beans. Melon jars are specifically about emulating the different forms of the squash that they cultivated.

Most melon jars are coiled round first, then carved and polished into their final shapes. Helen Shupla (of Santa Clara) perfected a method of forming a melon shape by coiling the jar, smoothing it, then pushing out ribs from the inside. She taught that method to her daughter, Jeannie, and to her Hopi son-in-law, Alton Komalestewa.

After Helen and Jeannie died, Alton got together with Jake Koopee and Jake showed him how he could work the same way using Hopi clay. Jake made three melon jars to show Alton, and they were the only melon jars Jake ever made.

Some Hopi potters still make melon jars and bowls, as do some potters at Jemez, San Ildefonso, Santa Clara, Ohkay Owingeh and Taos.