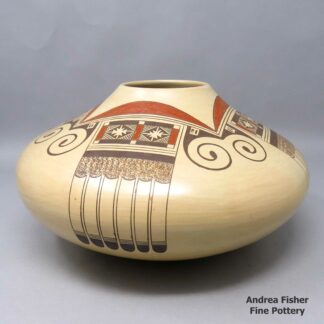

| Dimensions | 3.75 × 3.75 × 3.5 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good, normal wear |

| Signature | Sofia Medina Zia |

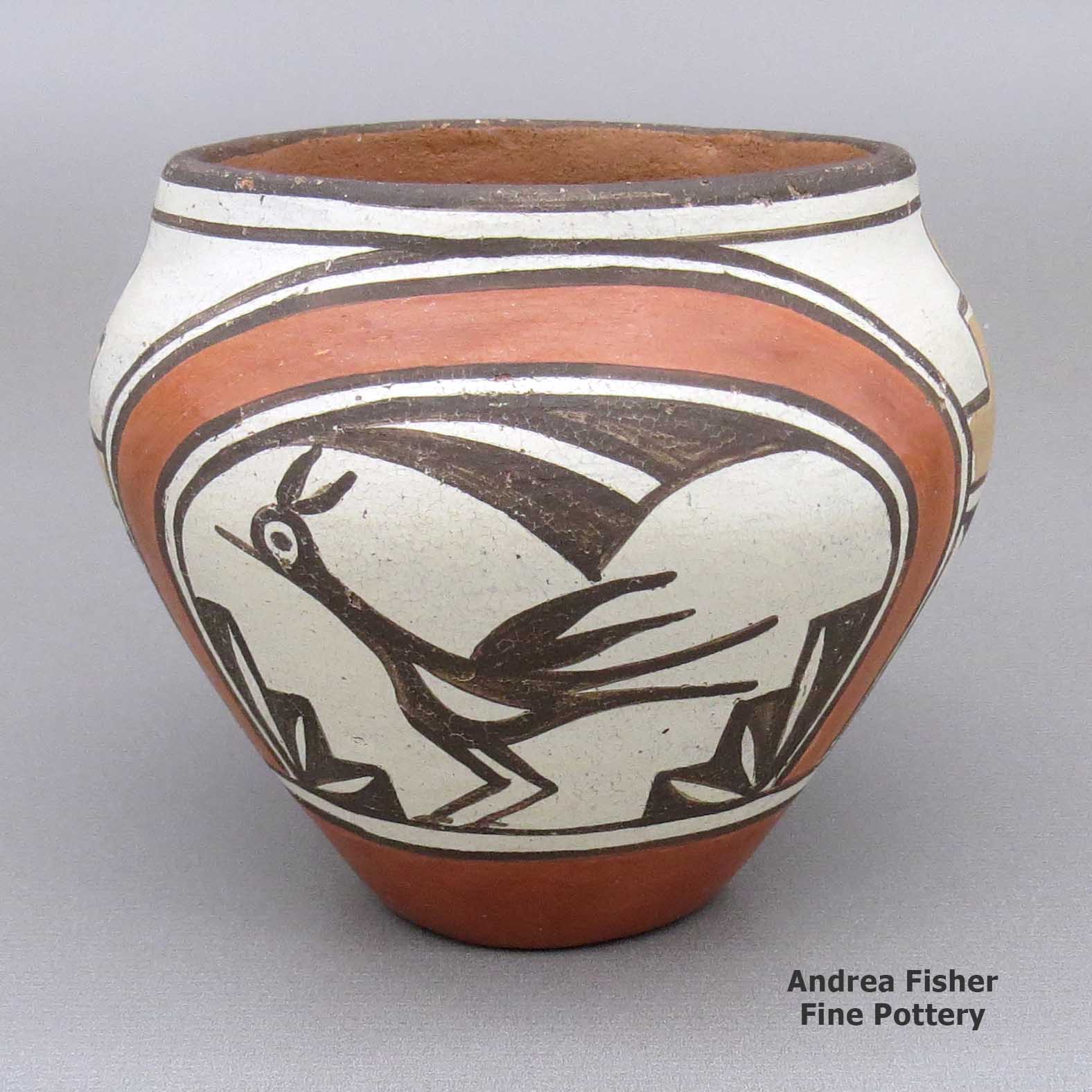

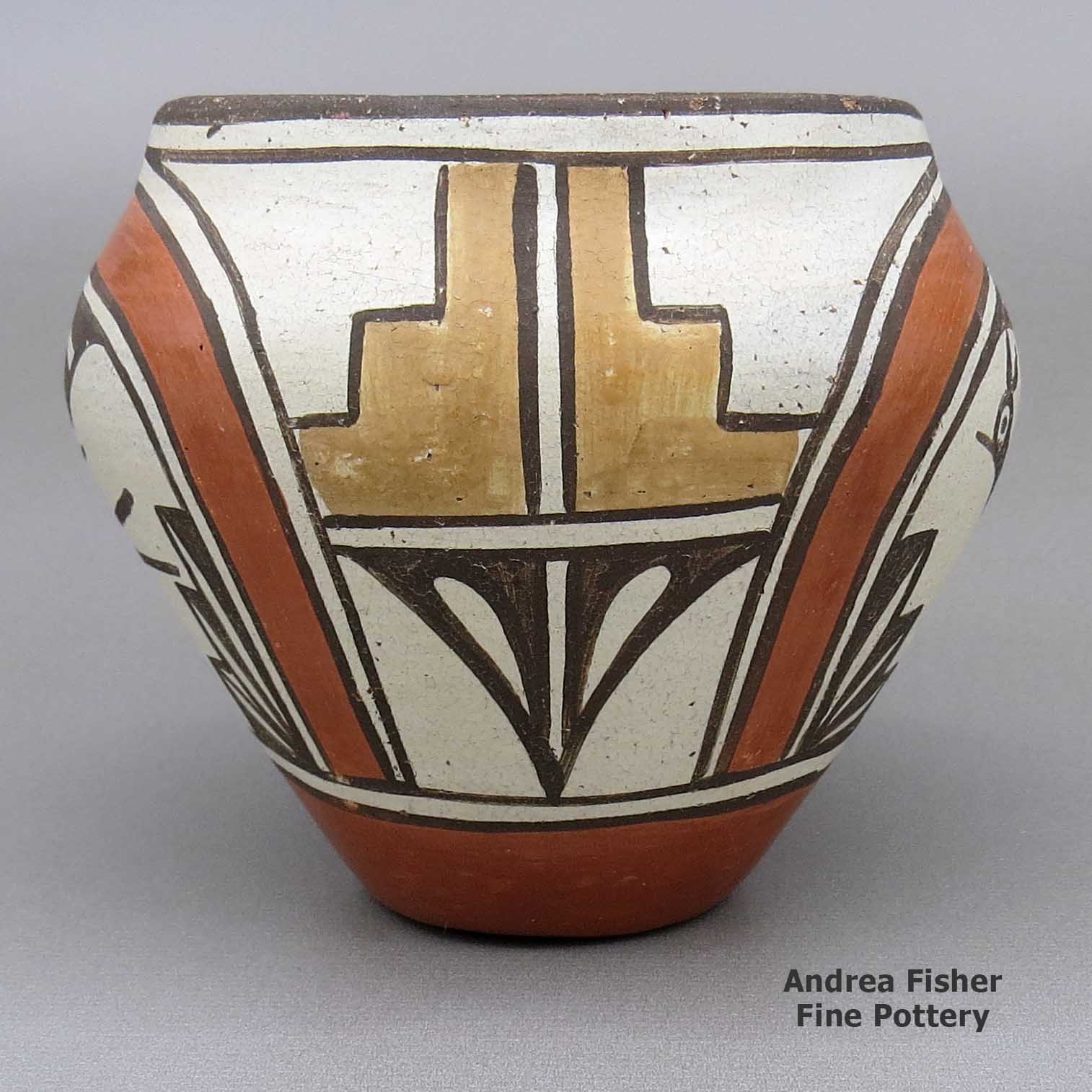

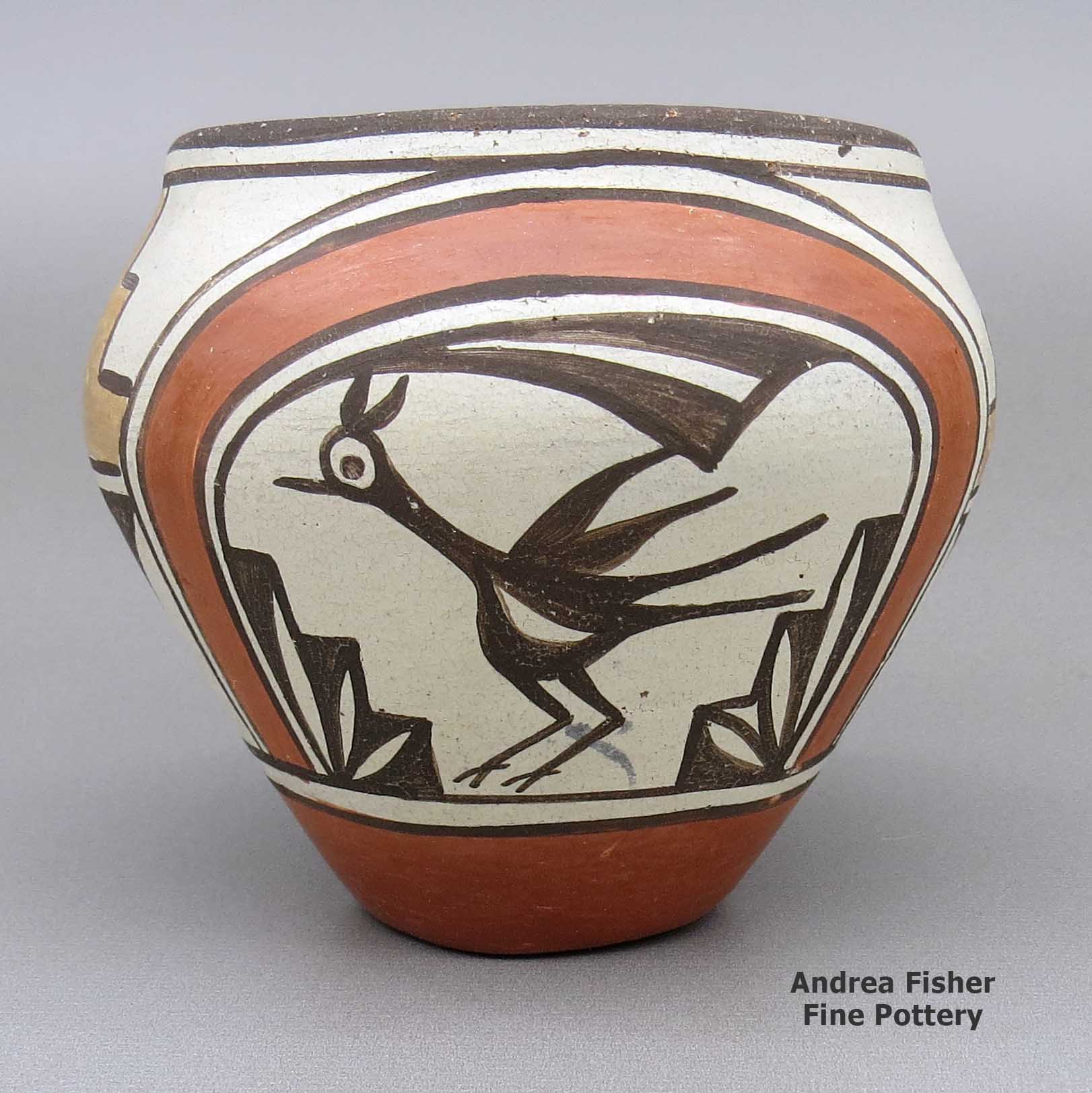

Sofia Medina, rsza3a067, Small polychrome jar with a roadrunner and geometric design

$275.00

Small polychrome jar with a traditional Zia rainbow, rain cloud, roadrunner and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Medina, Sofia

She married Rafael Medina in 1948 and moved into his grandmother's home. That's when she seriously began learning how to make pottery.

Rafael's grandmother was Trinidad Medina and she taught Sofia all the fundamentals she needed to become well-known for her fine, large traditional Zia ollas. Sofia also made smaller polychrome jars, dough bowls and chili bowls. Her favorite designs were traditional Zia rainbows, roadrunners, kiva steps and clouds.

Trinidad encouraged her to continue the family tradition and to pass it on to her children and grandchildren. Among Sofia's students were Marcellus and Elizabeth Medina, Lois Medina and Edna Medina Galiford.

Sofia was one of the exhibitors at the One Space/Three Visions exhibition in 1979 at the Albuquerque Museum. Her work can be found in many private collections around the world. It can also be found at the Heard Museum in Phoenix and the Peabody Museum at Harvard University in Boston.

Sofia passed on in 2010, less than a year after being given a Lifetime Achievement Allan Houser Legacy Award during the Santa Fe Indian Market Honoring Reception at Buffalo Thunder Resort and Casino on June 4, 2009.

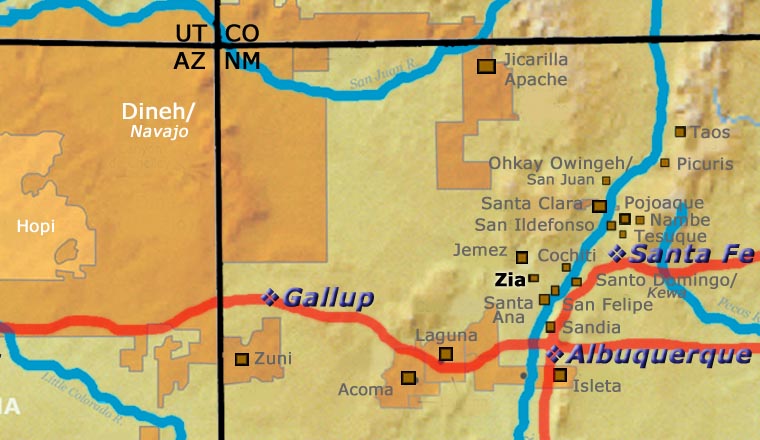

A Short History of Zia Pueblo

Zia Pueblo is situated in the Jemez Mountains with Jemez Pueblo to the north and Santa Ana Pueblo to the south. Despite its picture postcard setting, Zia's history for the last four hundred years has been difficult.

Antonio de Espejo led a small troop of Spanish explorers up the Jemez River and discovered Zia Pueblo in 1583. Espejo estimated there were about 4,000 inhabitants in a city of house blocks up to three and four stories high with five major plazas and many smaller ones. "The people are clean. The women wear a blanket over their shoulders tied with a sash at their waist - their hair cut in front, and the rest plaited so that it forms two braids, and above a blanket of turkey feathers," is how Espejo's scribe recorded it.

The people of Zia participated in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and when Spanish troops returned in 1682 and 1687, the Zias were able to repulse them. When more Spanish troops returned in 1688 they were finally successful in conquering the Zias. The Spanish killed many people, burned the pueblo and took many slaves back to Mexico with them.

When Don Diego de Vargas returned to northern Nuevo Mexico in 1692, the Zias sued for peace and accepted the rule of Spain almost immediately. In the revolt of 1696 the Zia, Santa Ana and San Felipe remained loyal to the Spaniards. In another revolt in 1728-9, Zia joined with Jemez, Santa Ana and Cochiti against the Spaniards and when things turned against them, they all fled to various mountain refuges while the Spaniards again burned everything they left behind.

The new Spanish government did little to protect the pueblos from the raids of nomadic Ute, Apache, Comanche and Navajo warriors. Nor did the government of Mexico after it declared independence from Spain in 1820 nor did the government of the United States after it acquired Zia in 1848. Zia fortunes slid in many ways and by the 1890s the tribe was down to just 98 members.

Today, the Pueblo of Zia numbers about 800 people, many of whom are active artists producing everything from pottery to jewelry to baskets to paintings, sculptures and wood carvings.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Photo courtesy of Jared Tarbell, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

Traditional Zia Design

On typical Zia Pueblo jars, the traditional Zia design pattern consists of three primary colors: mineral red and beeweed black on a slipped yellow-beige background. Traditionally, the base of the piece is well-slipped with red (the Earth band). There is often a red or black band around the rim (the sky band). In between, on the yellow-beige background, red and/or black images and symbols are painted in designs around the body.

The traditional design around the body consists of a flowing red ribbon, alternating up and down to make four panels around the piece. That's the rainbow which flows around at least two traditional roadrunner figures holding sprigs of yucca flowers in their claws. Sometimes there are two roadrunners below and two above that ribbon.

Rising from the Earth band, hanging from the sky band and attached to the rainbow ribbon are usually symbols evocative of clouds, rainfall and healthy cornfields. Those symbols can be sprinkled liberally around a pot, too.

Medina Family Tree - Zia Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

-

Rosalea Medina Toribio (c.1858-1950) & Mariano Toribio (c.1854-c.1918)

- Juanita Toribio Pino (1890-1987)

- Sofia Medina (1932-2010) & Raphael Medina (1929-1998)

- Marcellus Medina (1954-) & Elizabeth Medina (1956-)

- Kimberly Medina (1973-)

- Marcella Medina (1974-)

- Edna Medina Galiford (1957-)

- Lois Medina (1959-2002)

- Rachel Medina Raton (1961-) & Bernard Raton (Santa Ana)

- Marcellus Medina (1954-) & Elizabeth Medina (1956-)

- Sofia Medina (1932-2010) & Raphael Medina (1929-1998)

- Andrea Toribio Gachupin (1896-1956) & Jose Gachupin (ca. 1890-1953)

- Gloria Gachupin Chinana (1940-)

- Helen Gachupin (1931-1992)

- Maria Bridgett (c. 1890-)

- Candelaria Gachupin (1908-) & Antonio Gachupin

- Dora Tse-Pe & Johnnie Tse-Pe Gonzales (San Ildefonso)

- Candace Tse-Pe

- Gerri Tse-Pe

- Irene Tse-Pe

- Dora Tse-Pe & Johnnie Tse-Pe Gonzales (San Ildefonso)

- Trinidad Medina (c. 1890s-1965)(Antonio Gachupin's sister, aunt of Dora Tse Pe, teacher of Sofia Medina)

- Candelaria Gachupin (1908-) & Antonio Gachupin