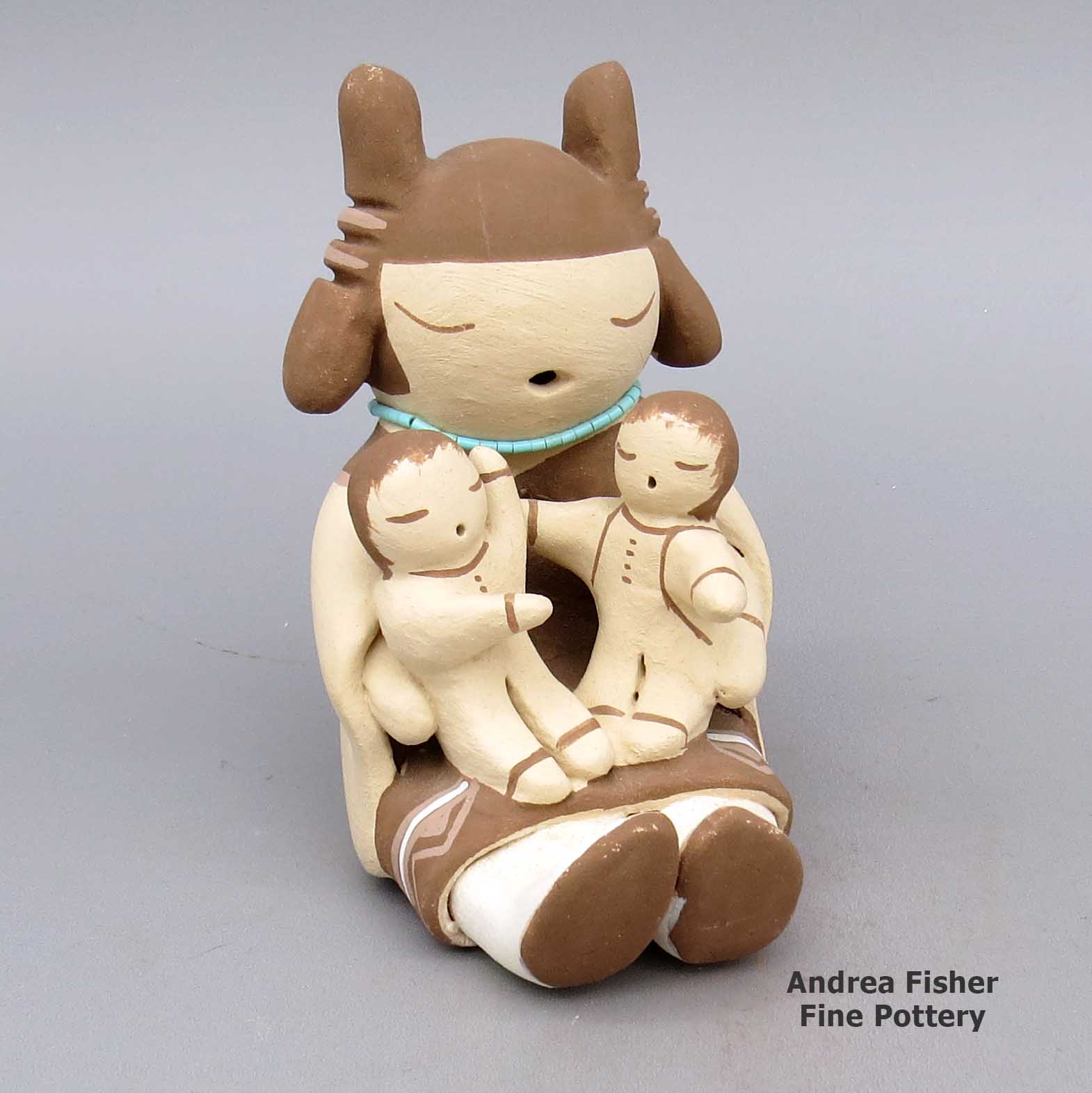

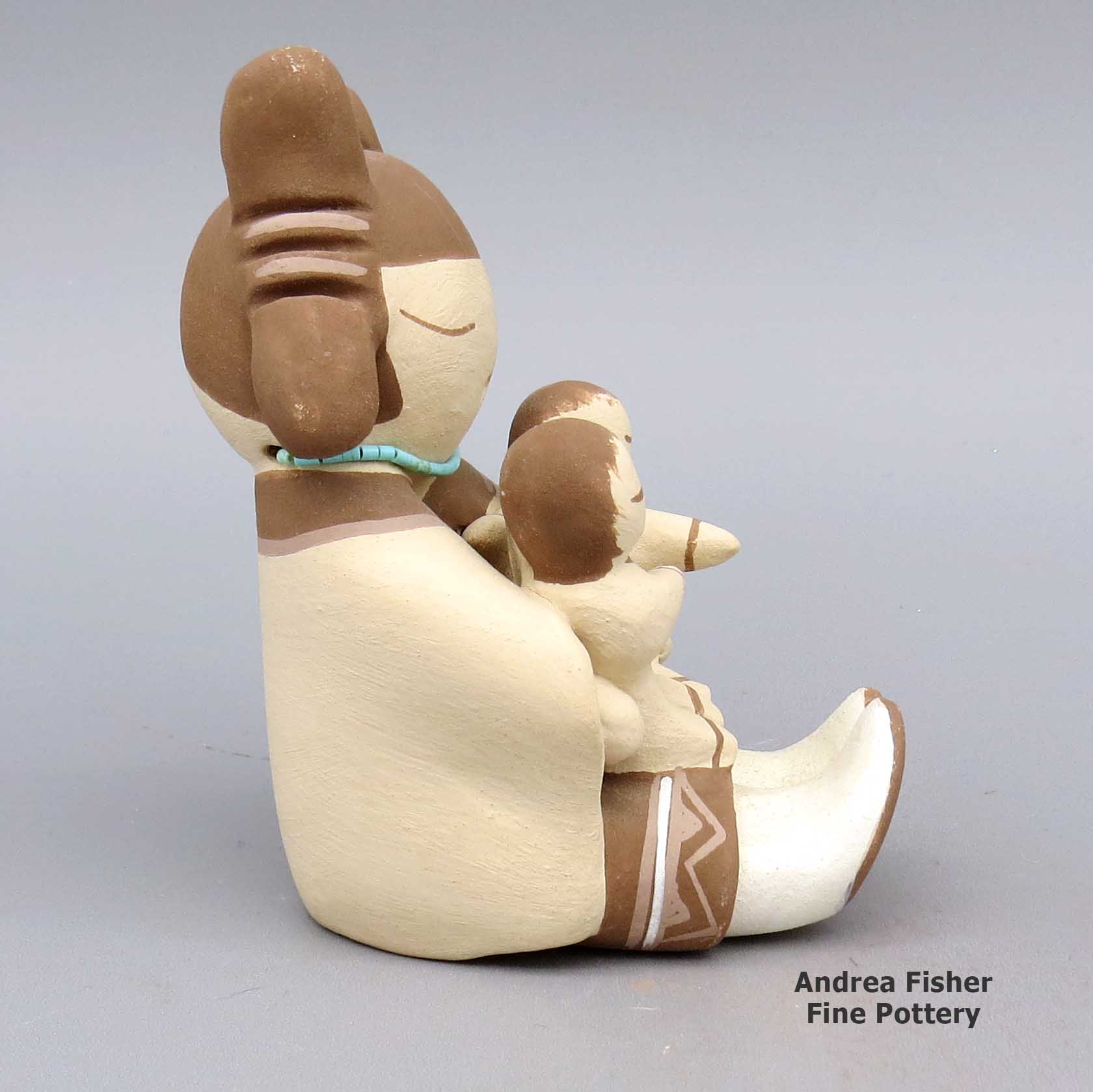

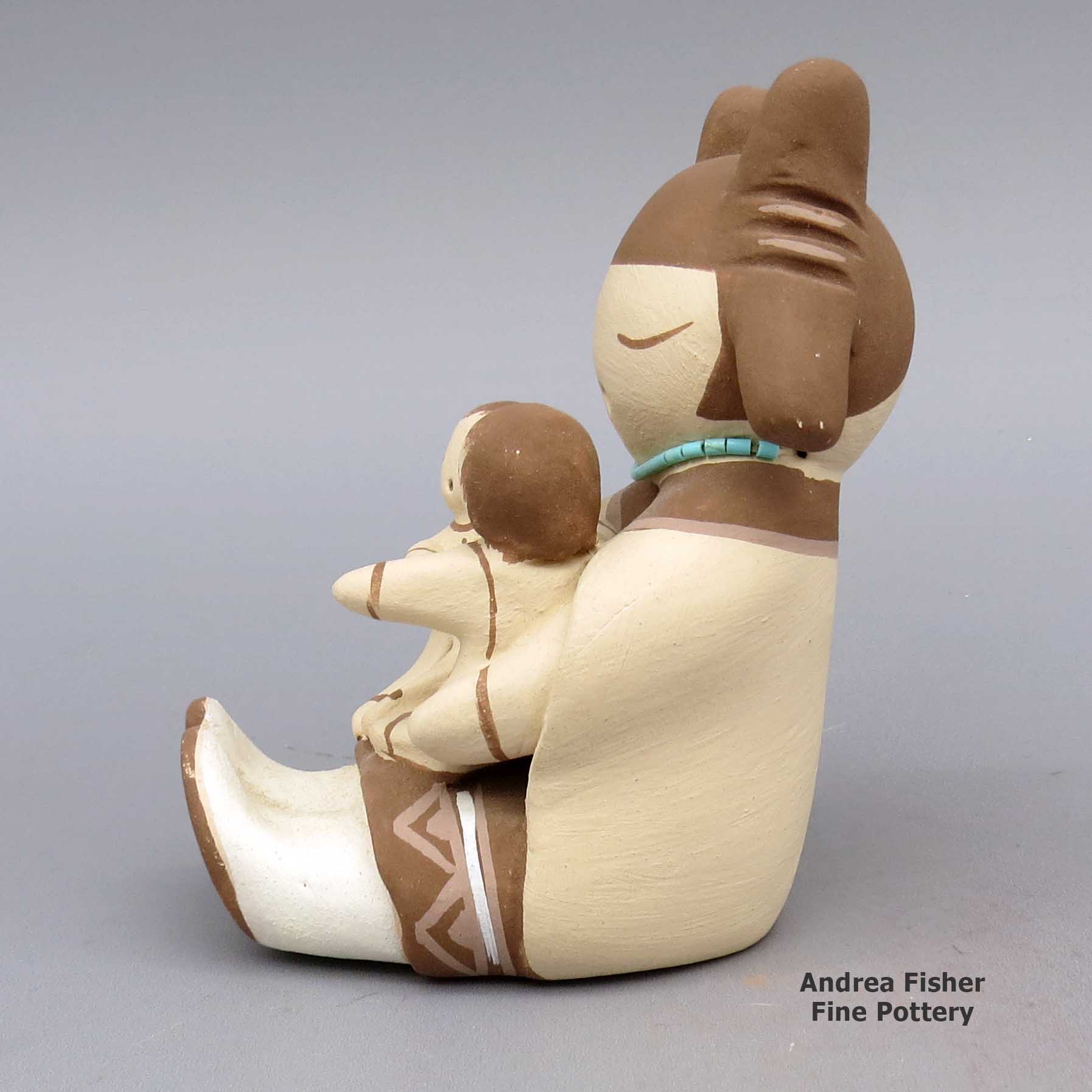

| Dimensions | 3 × 2 × 3.75 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Very good |

| Signature | Stella Teller Isleta, N.M. |

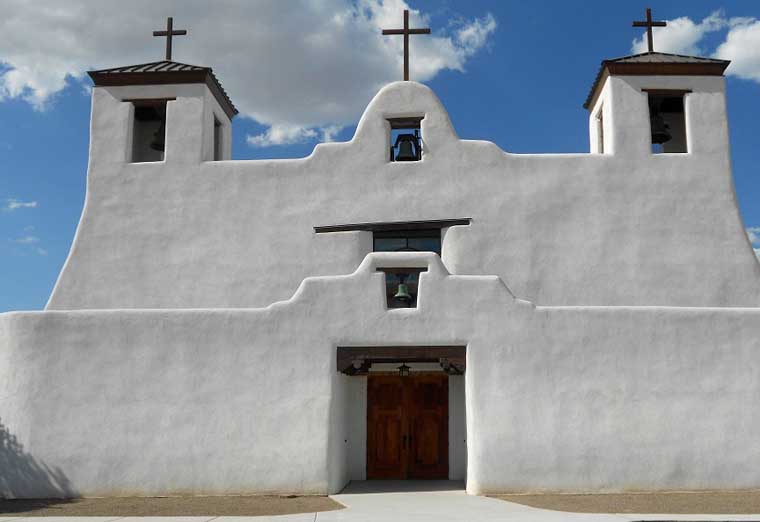

Stella Teller, lkle2l329: Polychrome storyteller with two children

$295.00

Two children are sitting on a grandmother storyteller figure who is wearing an inlaid strand of heishe beads

In stock

Brand

Teller, Stella

Stella's pieces are notable for their "sleeping eyes," overall light-blue to white coloring and often have strings of heishi beads either inlaid or painted on. Some of her pieces have found their way into the collections of the Peabody Museum at Harvard College in Boston, the Folk Museum in Berlin, Germany, and into the Wright Collection, Walton-Anderson Collection and the personal collections of Frank Kinsel and Peter B. Carl.

Her favorite designs include clouds, rain, turtles, Pueblo dancers and kiva steps. Her favorite styles include storytellers, Nativities, jars, bowls, wedding vases, canteens and effigies.

Stella has passed her knowledge on to her daughters: Chris, Mona, Robin and Lynette, each of whom has gone on to become an award-earning potter in their own right.

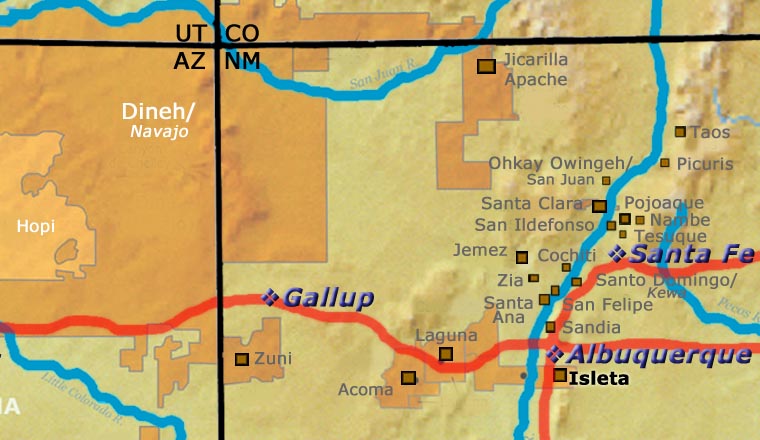

A Short History of Isleta Pueblo

Isleta Pueblo was founded in the 1300s. Archaeologists have put forth various ideas as to where the people came from with some scholars saying they migrated north from Mogollon/Mimbres settlements to the south while others say they migrated southeastward from either Chaco Canyon in the 1100s and 1200s or from the Four Corners area in the 1200s and 1300s. There is every possibility they are an indigenous Tano population that was merged with Aztec migrants coming north from central Mexico and they were never part of the Chacoan world. Their Tiwa language is shared with nearby Sandia Pueblo and a very similar tongue is spoken to the north at Taos and Picuris Pueblos. The two dialects are sometimes referred to as Southern and Northern Tiwa. The Taos people also consider that some of their ancestors migrated north from Aztec lands long ago while others came from the north.

When the Spanish arrived in the area they named the pueblo "Isleta" (meaning: island). The residents were relatively accommodating to the Spanish priests when compared to the reception the same priests got in other areas of Nuevo Mexico (making Isleta something of an "island of safety" for the Spanish in an ocean of hostility). When the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 happened, Isleta either couldn't or wouldn't participate in the rebellion.

When the Spanish governor was evicted from Santa Fe he went to Albuquerque, then to Isleta and gathered his troops. With warriors from the northern pueblos harassing their every move, none of the Spaniards wanted to go back and fight so when they left Isleta and headed south, many Isletans went south to the El Paso area with them. Those who went south were allowed to establish their own pueblo at Ysleta del Sur, a place that at the time was beyond the boundaries of the village of El Paso.

Other Isletans fled to the Hopi settlements in Arizona and returned after the fighting was clearly over, many with Hopi spouses. When the Spanish returned in 1682 they found the Isleta mission church burned and the main structure was being used as a livestock pen. When Don Diego de Vargas came in 1692 with troops intent on reconquering New Mexico, they found the whole village of Isleta empty and burned.

The governor ordered the pueblo be rebuilt and resettled so residents were brought in from Taos and Picuris to the north and from Ysleta del Sur to the south. By 1720 a new, more grandiose mission had been built on the foundations of the first.

Over the next century some dissident members of the Laguna and Acoma Pueblo communities migrated to Isleta. While they were welcomed into the main Isleta pueblo at first, friction developed over the years until in the late 1800s, the small communities of Oraibi and Chicale were established. Most of the newcomers moved to one or the other but some returned to Acoma and Laguna.

For more info:

Pueblo of Isleta at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Isleta official website

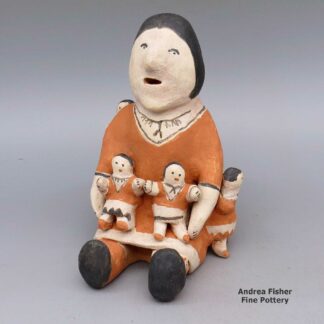

About the Storyteller

Historically, clay figures have been present in the Pueblo pottery tradition for more than a thousand years. However, figures and effigies were denounced as "works of the devil" by the Spanish missionaries in New Mexico between 1540 and 1820. Before and after that time the art of making figurative sculpture flourished, especially at Cochiti Pueblo. At Cochiti, the forms of animals, birds, caricatures of outsiders and, more recently, images of mothers and grandfathers telling stories and singing to children have multiplied.

The "storyteller" is an important role in the tribes as parents are often too busy working and raising kids to pass on their tribal histories. The Native American people did not develop a written language to record anything for posterity. Some tribes still refuse to create one. The closest thing they had to a written language was recorded on pottery and textiles, in the form of painted designs that decorate that pottery and textiles.

The storyteller's role was to preserve and retell and pass down the oral history of his people in their native language. In most tribes that role was fulfilled by elder men.

The first recorded storyteller figure was created in 1964 by Cochiti Pueblo potter Helen Cordero in memory of her grandfather, Santiago Quintana. She gathered her clay from a secret sacred place on the lands of her pueblo. Then she hand-coiled, hand painted and fired that first storyteller figure the traditional way: in the ground. Helen never used any molds or kilns to make her pottery.

Helen's creation immediately struck a chord throughout all the pueblos as the storyteller is a figure central to all their societies. Most tribes also have the figure of the Singing Maiden in their pantheon and in many cases, the mix of Singing Maiden and Storyteller has blurred some lines in the pottery world.

Today, as many as three hundred potters in thirteen pueblos have created storytellers. Their storytellers are not only men and women but also Santa’s, mudheads, koshares, bears, owls, eagles and other animals, sometimes encumbered with children numbering more than one hundred! Each potter has also customized their storyteller figures to more closely reflect the styles and dress of their own tribes, often even of their own clans.

Teller Family Tree - Isleta Pueblo

Disclaimer: This "family tree" is a best effort on our part to determine who the potters are in this family and arrange them in a generational order. The general information available is questionable so we have tried to show each of these diagrams to living members of each family to get their input and approval, too. This diagram is subject to change should we get better info.

- Marcellina Jojola (c. 1860s-)

- Emily Lente Carpio (c. 1880s-)

- Felecita Jojola (c. 1900s-) & Rudy Jojola

- Stella Teller (1929-) and Louis Teller

- Chris Teller Lucero (1956-)

- Marie (Robin) Teller Velardez (1954-) and Ray Velardez

- Lesley Teller Velardez (1973-)

- Mona Blythe Teller (1960-)

- Christopher Teller

- Nicol Teller Blythe (1978-)

- Lynette Teller (1963-)

- Stella Teller (1929-) and Louis Teller

- Felecita Jojola (c. 1900s-) & Rudy Jojola