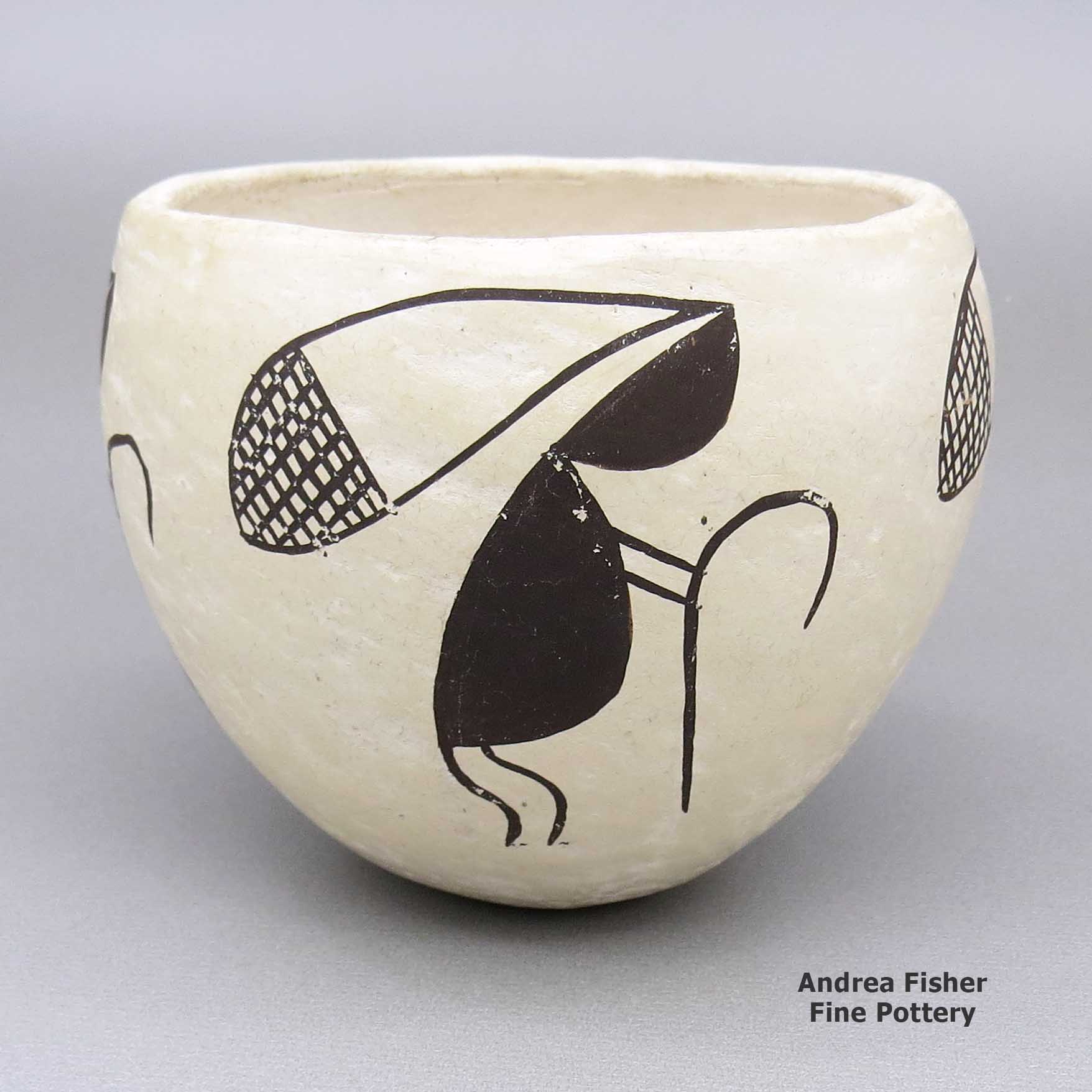

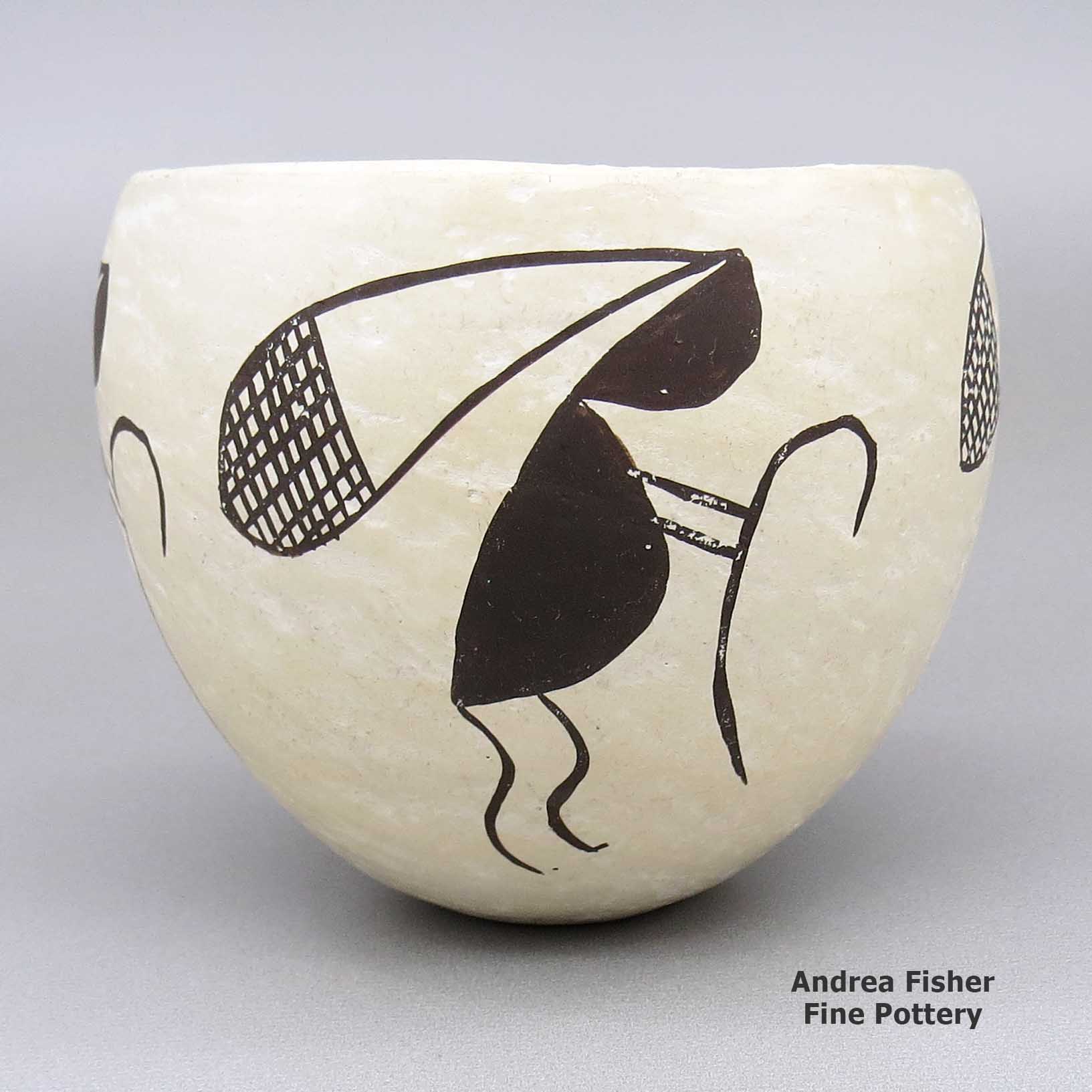

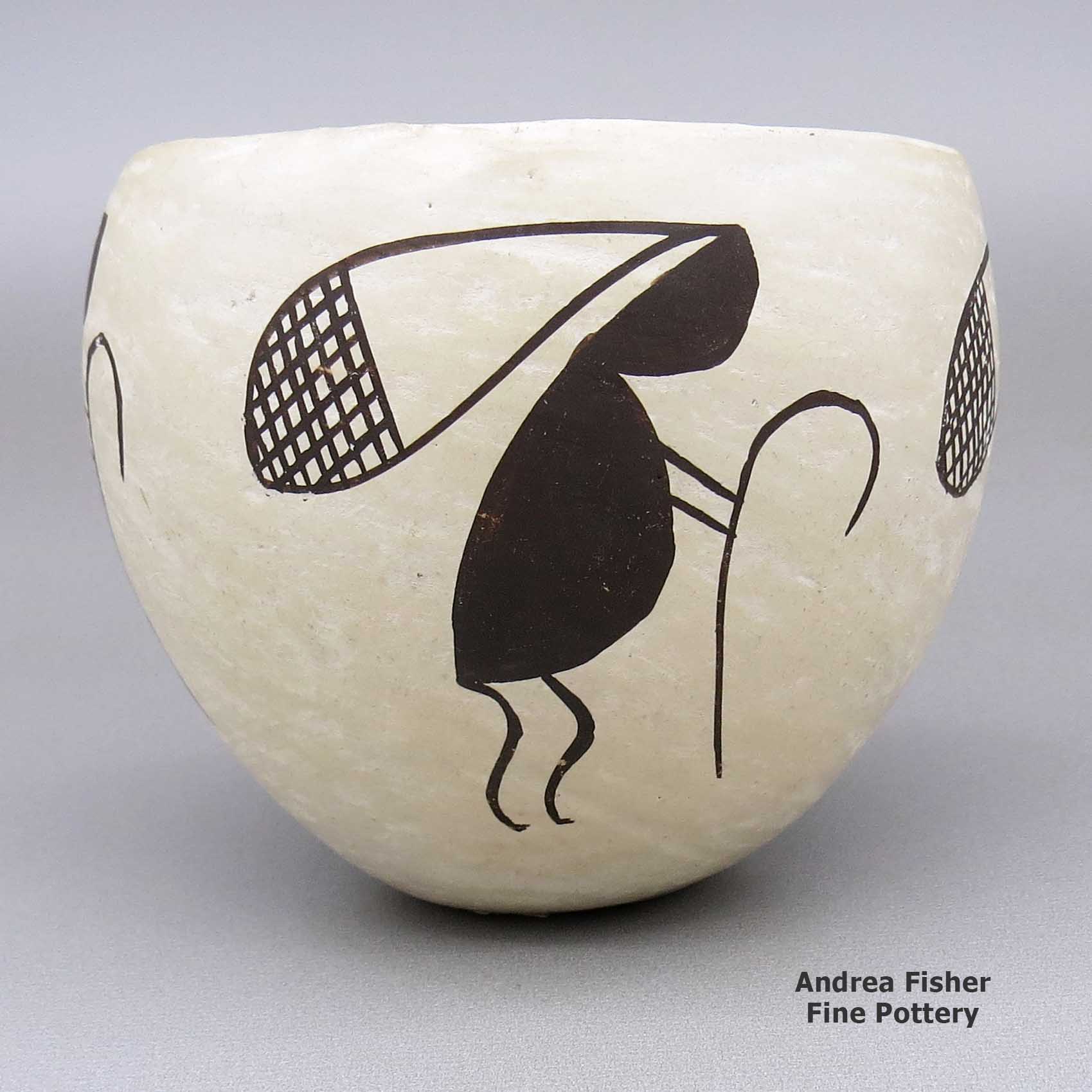

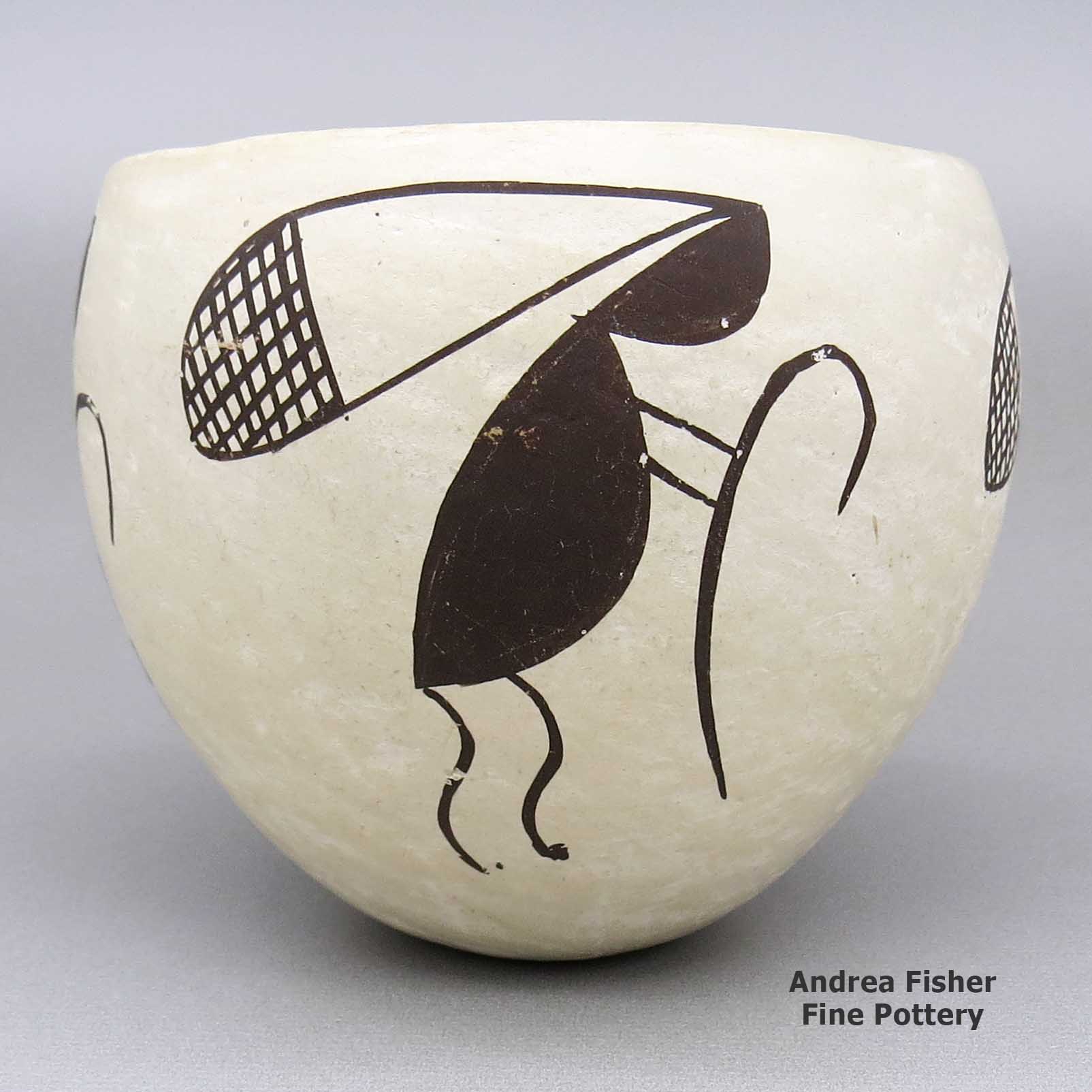

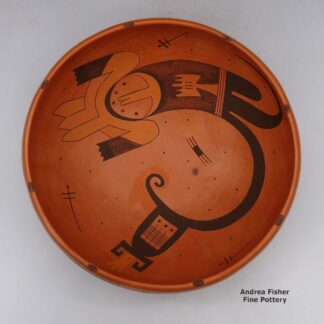

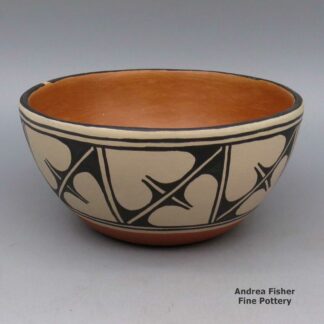

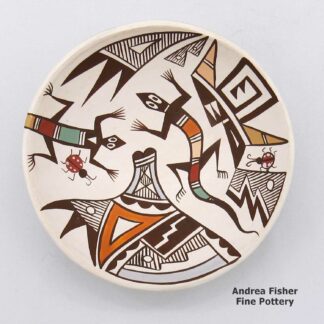

| Dimensions | 4 × 4 × 3.5 in |

|---|---|

| Signature | Acoma N. Mex., plus a bird hallmark |

| Condition of Piece | Very good, has sticker residue and rubbing on bottom and scratches on sides |

Unknown Acoma Potter, zzac2m553a, Black-on-white bowl with a Mimbres kokopelli design

$175.00

A black-on-white bowl decorated outside with a four-panel Mimbres kokopelli design

In stock

Brand

Unknown Acoma Potter

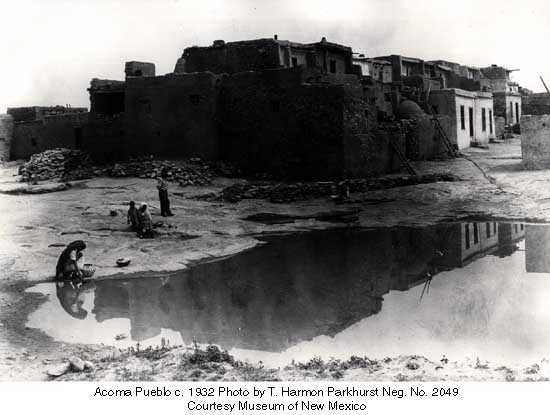

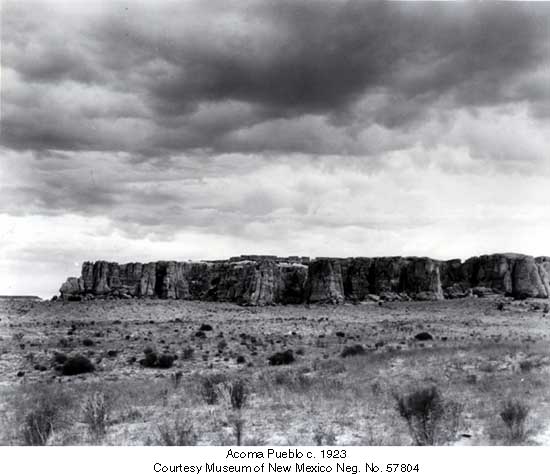

A Short History of Acoma Pueblo

According to Acoma oral history, the sacred twins led their ancestors to "Ako." Ako turned out to be a magical mesa composed mostly of white rock. There the sacred twins instructed the ancestors to make that mesa their home. Acoma Pueblo is called "Sky City" because of its position atop the high mesa.

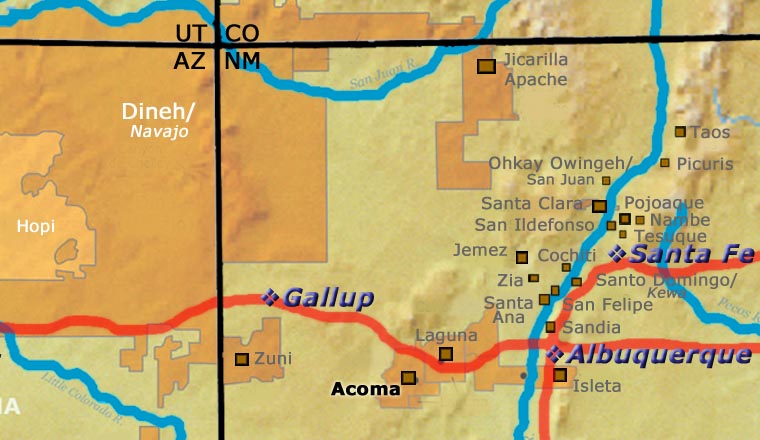

Acoma, Old Oraibi (at Hopi) and Taos all lay claim to being the oldest continuously inhabited community in the U.S. Those competing claims are hard to settle as each village can point to archaeological remnants close by to substantiate each village's claim. Acoma is located about 60 miles west of Albuquerque in a landscape littered with the ruins of ancient pueblos, many more than 1,000 years old.

The people of Acoma have an oral tradition that says they've been living in the same area for more than 2,000 years. Archaeologists feel more that the present pueblo was established near the end of the major migrations in the 1200 and 1300s. The location is essentially on the boundary between the Mogollon (Mimbres), Hohokam (Salado) and Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloan) cultures. Each of those cultures has had an impact on the styles and designs of Acoma pottery, especially since modern potters have been getting the inspiration for many of their designs from pot shards they have found while walking on pueblo lands.

Francisco Vasquez de Coronado ascended the cliff to visit Acoma in 1540. He afterward wrote that he "repented having gone up to the place." But the Spanish came back later and kept coming back.

Around 1598 relations between the Spanish and the Acomas took a nasty turn with the arrival of Don Juan de Oñaté and the soldiers, settlers and Franciscan monks that accompanied him. After making the arduous ascent to the mesa top, de Oñaté decided to force the Acomas to swear loyalty to the King of Spain and to the Pope. When the Acomas realized what the Spanish meant by that, a group of Acoma warriors attacked a group of Spanish soldiers and killed 11 of them, including one of de Oñaté's nephews.

De Oñaté retaliated by attacking the pueblo. His troops burned most of it and killed more than 600 people. Another 500 people were imprisoned by the Spanish. Males between the ages of 12 and 25 were sold into slavery. 24 men over the age of 25 had their right foot amputated. Many of the women over the age of 12 were also forced into slavery. Most were parceled out among Catholic convents in Mexico City.

Two Hopi men were also captured at Acoma. The Spanish cut one hand off of each and sent them home to spread the word about Spain's resolve to subjugate the inhabitants of Nuevo Mexico. Spanish monks did make the trip a few years later but Spanish military made hardly an appearance in Hopiland.

When word of the massacre (and the punishments meted out after) got back to King Philip in Spain, he banished Don Juan de Oñaté from Nuevo Mexico. Some Acomas had escaped that fateful Spanish attack and returned to the mesa top in 1599 to begin rebuilding.

In 1620 a Royal Decree was issued which established civil offices in each pueblo and Acoma got its first governor. That didn't help the people any as those appointed to the government positions were also those most on the take with the Spanish authorities. By 1680, the situation between all of the pueblos and the Spanish had deteriorated to the point where the Acomas were extremely willing participants in the 1680 Pueblo Revolt.

After the successful Pueblo Revolt pushed the Spanish back to Mexico, refugees from other pueblos began to arrive at Acoma. Most feared the eventual Spanish return and probable reprisals. That strained the resources of Acoma badly. Then the Spanish returned in force and residents of the pueblo had to make a hard decision. Many of the refugees chose to try a peaceful solution: they relocated north to the ancient Laguna area and made peace with the Spanish as soon as they reappeared in the region. Acoma held out against the Spanish for awhile but soon capitulated.

Over the next 200 years, Acoma suffered from breakouts of smallpox and other European diseases to which they had no immunity. At times they would side with the Spanish against nomadic raiders from the Ute, Apache and Comanche tribes. Eventually New Mexico changed hands. Then the railroads arrived and Acoma became dependent on goods made in the outside world.

For many years the villagers were content on the mesa. Now most live in villages on the valley floor where water, electricity and other necessities are easily available. A few families still make their permanent home on the mesa top. The old pueblo is used almost exclusively these days for ceremonial celebrations.

For more info:

Acoma Pueblo at Wikipedia

Pueblo of Acoma official website

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, © 2001

Acoma & Laguna Pottery, Rick Dillingham with Melinda Elliott, ISBN 0-933452-32-2, School of American Research Press, © 1992

Upper photo courtesy of Marshall Henrie, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About the Mimbres Culture

The Mimbres culture existed in the Mimbres Valley of southern New Mexico from about 850 CE to about 1150 CE. They were a sub-culture of the greater Mogollon culture that extended from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre Mountains, north to the San Andres Mountains and northwest along the Mogollon Rim to the vicinity of today's Springerville, AZ.

North of the Gila Mountains was the influence of the Great Houses of the Chaco culture. Through comparisons of imagery and the colors used, it has been conjectured that Chaco was a more male dominant society while Mimbres was more female dominant. Both areas were settled, built, flowered and abandoned on almost exactly the same time schedules. But at the time of abandonment, the folks of Chaco mostly moved north while those of the Mimbres valley mostly went south.

The Mimbres people were among the first cultures that evolved their own forms of imagery and means of telling stories through those images. The Classic Mimbres period was the height of their creativity, from about 1000 CE to about 1150 CE. Then things changed and migrations began in earnest. Many moved south and brought some of their art to Paquimé. Others pushed north and then west, around the Gila Mountains. By 1200 CE the vast majority of the people in the area of the Mimbres Valley had moved elsewhere.

Most Mimbres pottery was black-on-white. Around 1120 CE there was an influx of migrants from Hohokam and Salado areas to the west. That's about when the first black-on-red pottery appeared in the Mimbres villages. Some of the imagery we see today from many of the Northern and Middle Rio Grande pueblos had its origins in the Mimbres Valley.

Substantial depopulation of the area occurred shortly after 1150 CE but there were many small surviving populations scattered around. Over time, these melted into the surrounding cultures with many families moving north to Acoma, Zuni and Hopi while others moved south to Casas Grande and Paquimé.

The greater Mogollon culture spanned the countryside from the west coast of Mexico east across the Sierra Madre to Paquimé, then north through the Mimbres Valley to the edge of the White Sands and then northwest along the Mogollon Rim into east-central Arizona.

The time period from about 850 CE to about 1000 CE is classed the Late Basketmaker III period across the Southwest. The time period was characterized by the evolution of square and rectangular pithouses with plastered floors and walls. Ceremonial structures were generally dug deep into the ground. In the Mimbres Valley area, local forms of pottery have been classified as early Mimbres black-on-white (formerly Boldface Black-on-White), textured plainware and red-on-cream.

The Classic Mimbres phase (1000 CE to 1150 CE) was marked with the construction of larger buildings in clusters of communities around open plazas. Some constructions had up to 150 rooms. Most groupings of rooms included a ceremonial room, although smaller square or rectangular underground kivas with roof openings were also being used. Classic Mimbres settlements were located in areas with well-watered floodplains available, suitable for the growing of maize, squash and beans. The villages were limited in size by the ability of the local area to grow enough food to support the village.

Pottery produced in the Mimbres region is distinct in style and decoration. Early Mimbres black-on-white pottery was primarily decorated with bold geometric designs, although some early pieces show human and animal figures. Over time the rendering of figurative and geometric designs grew more refined, sophisticated and diverse, suggesting community prosperity and a rich ceremonial life. Classic Mimbres black-on-white pottery is also characterized by bold geometric shapes executed with refined brushwork and very fine linework. Designs may include figures of one or more humans, animals or other shapes, bounded by either geometric decorations or by simple rim bands. A common figure on a Mimbres pot is the turkey, others are the thunderbird, rabbit and various anthropomorphic, half-human figures. There are also a lot of different fish depicted, some are species found only in the Gulf of California (hundreds of miles away across the desert).

A lot of Mimbres bowls (with kill holes) have been found in archaeological excavations but most Mimbres pottery shows evidence it was actually used in day-to-day life and wasn't produced just for burial purposes.

There's a lot of speculation as to what happened to the Mimbres people as their countryside was rapidly depopulated after about 1150 CE. The people of Isleta, Acoma and Laguna find ancient Mimbres pot shards on their pueblo lands, indicating that pottery designs from the Mimbres River area migrated north. There are similar designs found on pot shards littering the ground around Casas Grandes and Paquimé near Mata Ortiz and Nuevo Casas Grandes in northern Mexico. Other than where they went, the only reasons offered for why they left involve at least small scale climate change. The usual comment is "drought" but drought could have been brought on by the eruption of a volcano on the other side of the planet, or a small change in the El Nino-La Nina schedule. Whatever it was that started the outflow of people, it began in the Mimbres River area and spread outward from there. Excavations in the eastern Mimbres region (nearer to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico) have shown that the people adapted to new circumstances and that adaptation itself moved them closer into alignment with surrounding villages and cultures. Eventually they just kind of merged into the background population.

The groups that moved south and built up Paquimé and Casas Grandes became powerful and wealthy over the next couple hundred years. Then they seem to have lost a war in the mid-1400s and the survivors were forced to migrate to the west, to a land a bit more hospitable for them at the time. It's also quite possible that they were defeated by volcanic eruptions on the other side of the planet: the 1100s, 1200s and 1300s were a time of migration in many parts of the world because of continuing bad weather events. The Little Ice Age that saw temperatures in the Northern Hemisphere drop as much as 2°C began in the early 1300s and lasted into the mid 1800s. NASA feels that this was mostly a result of large volumes of volcanic aerosols being pumped into the atmosphere at the time.