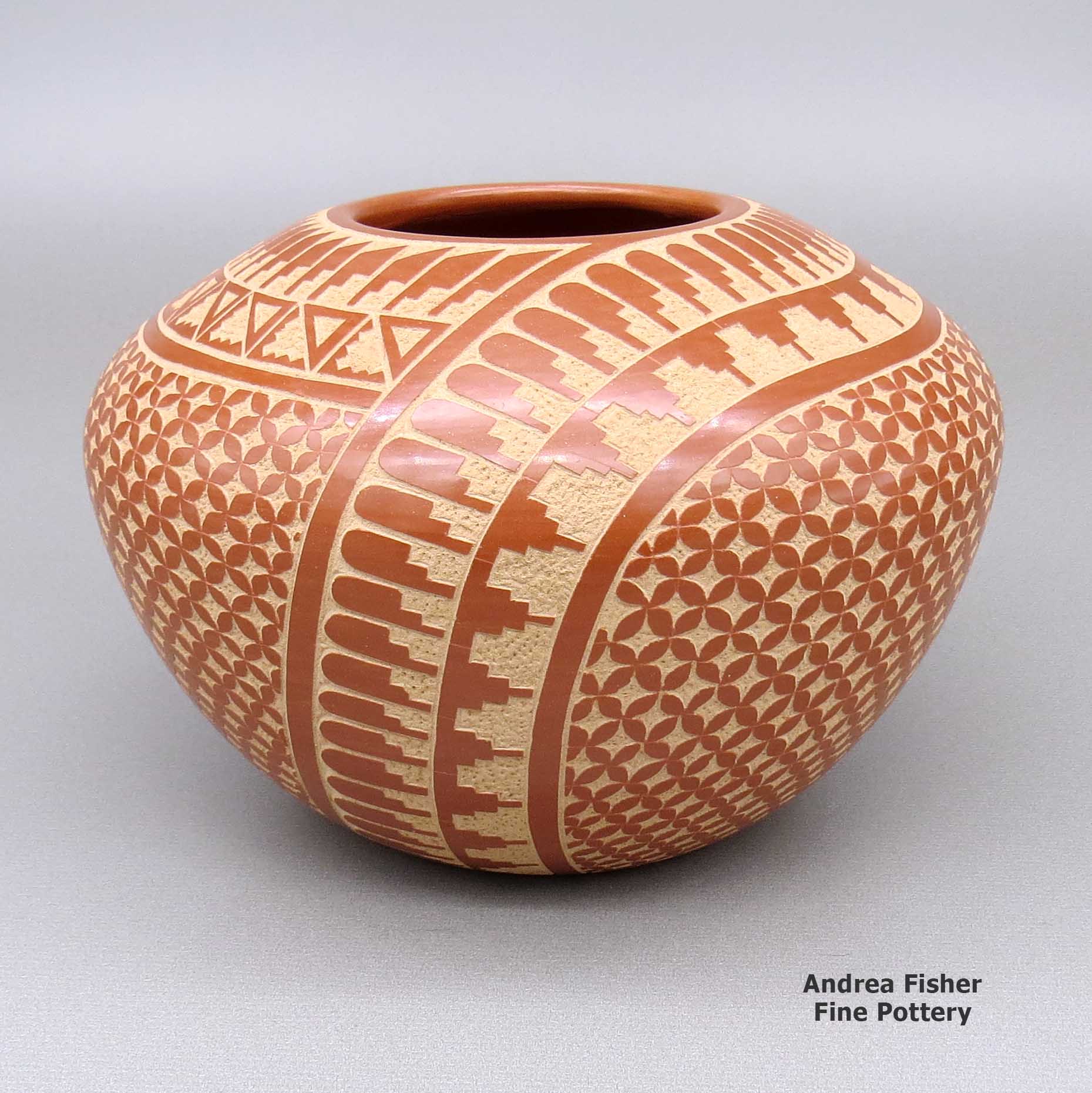

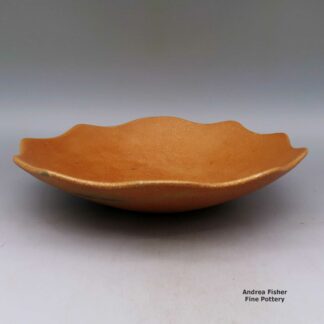

| Dimensions | 5.5 × 5.5 × 4 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Date Born | 2022 |

| Signature | Wilma Baca-Tosa Jemez NM |

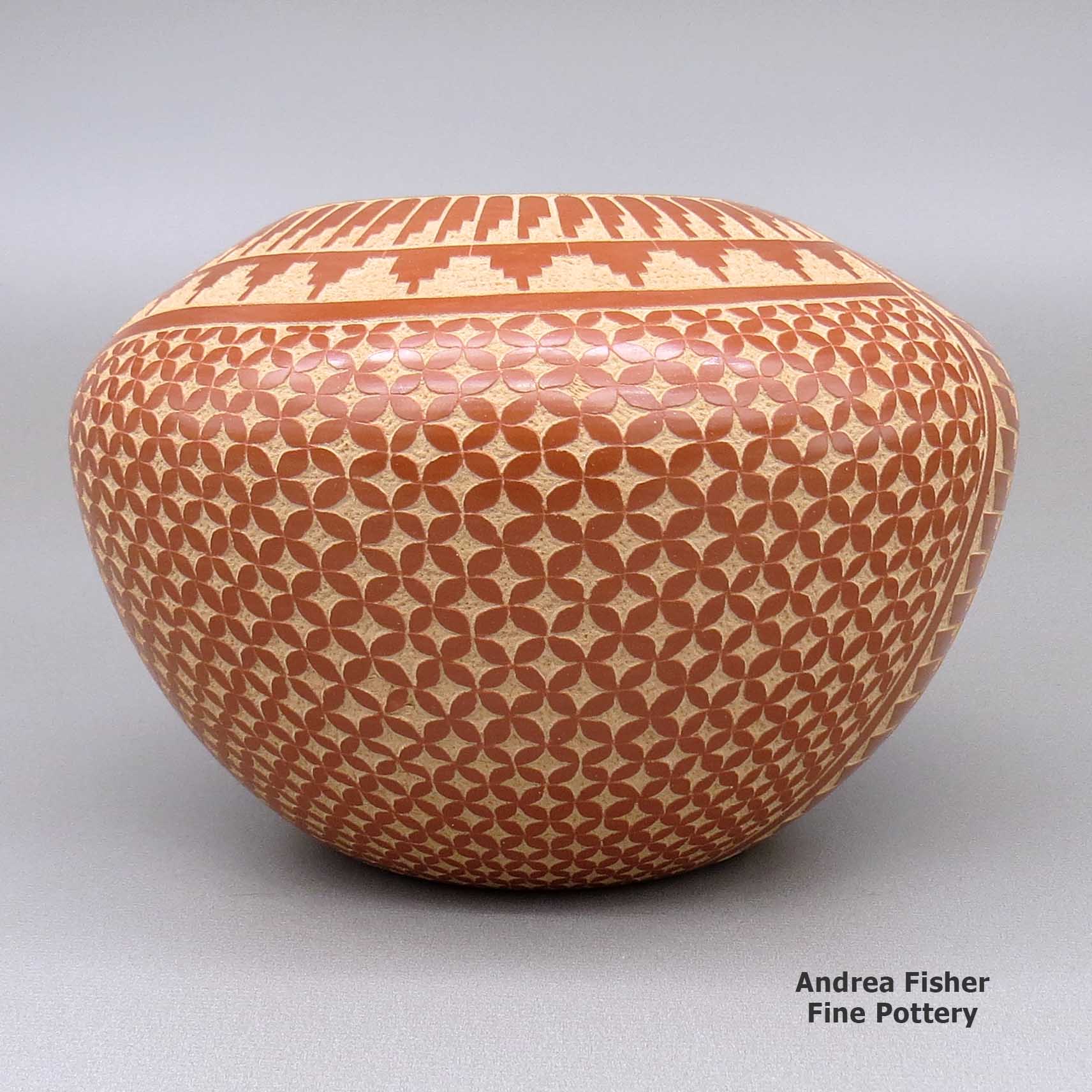

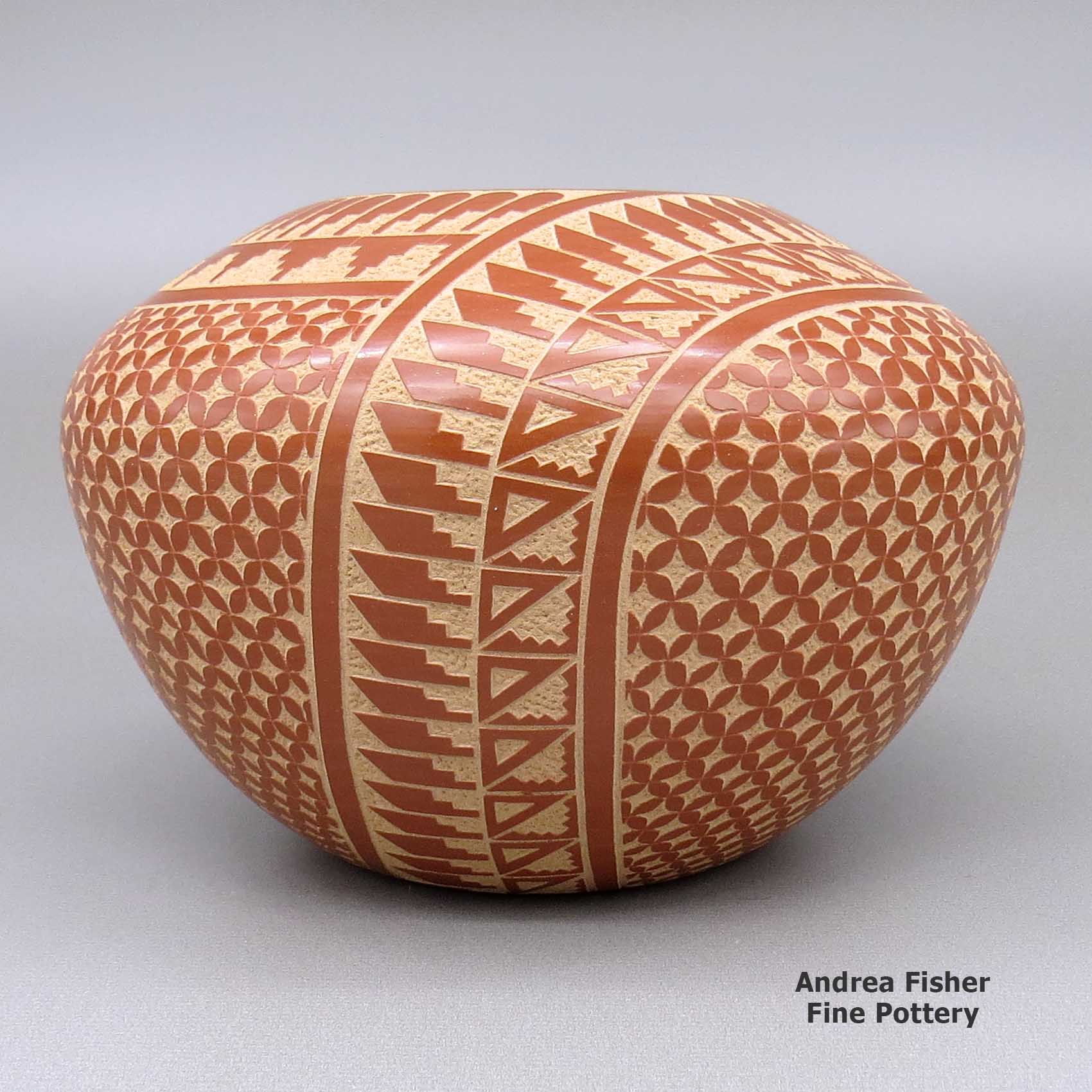

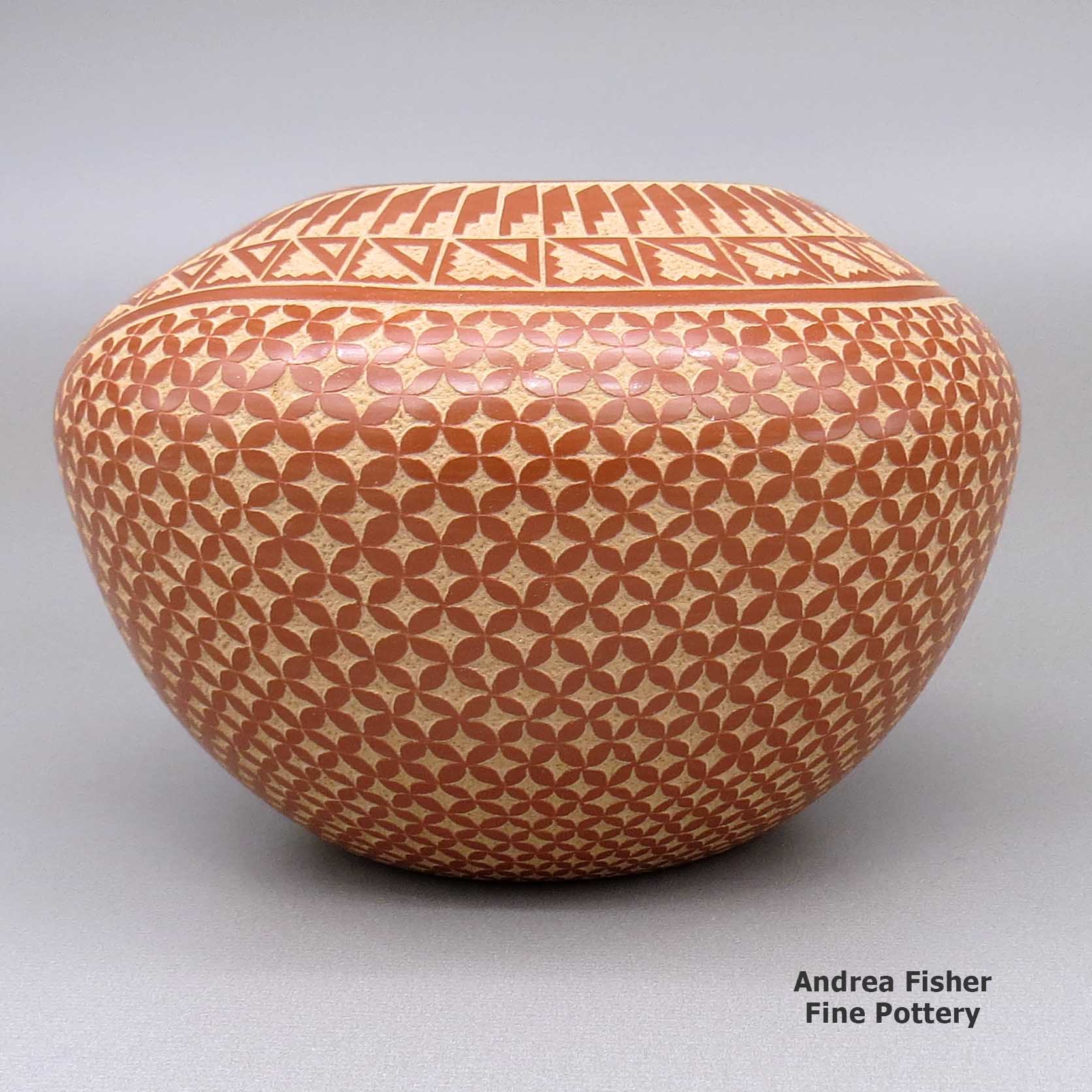

Wilma Baca Tosa, zzje2k290, Bowl with sgraffito geometric design

$675.00

A red bowl decorated with a sgraffito feather, kiva step, snowflake and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Tosa, Wilma Baca

Wilma Baca, (New Wheat), was born to John and Linda Baca in Jemez Pueblo in September 1967. By the time she was five, she already had her hands in the clay. Her grandmother, Marie Reyes Shendo, saw that and took Wilma under her wing.

Wilma Baca, (New Wheat), was born to John and Linda Baca in Jemez Pueblo in September 1967. By the time she was five, she already had her hands in the clay. Her grandmother, Marie Reyes Shendo, saw that and took Wilma under her wing.Marie had been one of the original potters in the 1920s attempt to revive the Jemez pottery tradition. She taught Wilma the fundamentals of making pottery the traditional way using ancient methods passed down from their ancestors.

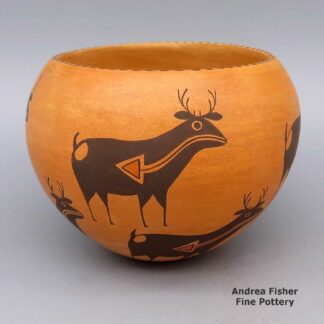

Wilma specializes in hand coiled, stone polished and traditionally decorated Jemez pottery. She makes redware bowls, jars, seed pots, vases and wedding vases.

Wilma has been etching her pottery using the free-hand sgraffito technique since 1989. Her favorite piece to make is the wedding vase because of its meaning: "The spouts represent two separate lives, the bridge across the middle unites these separate lives as one," she says.

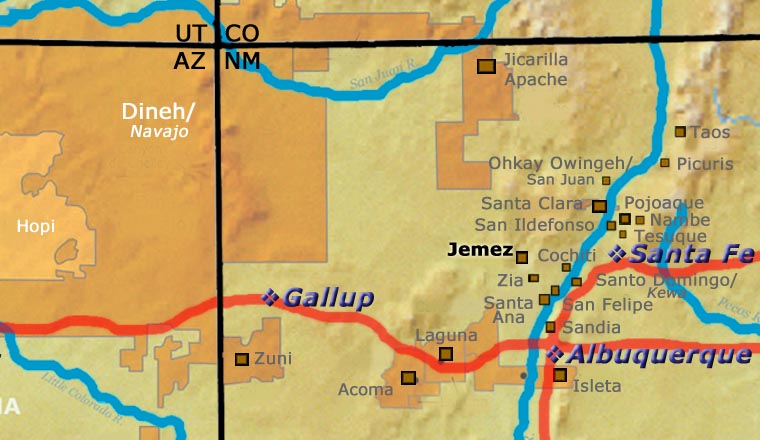

A Short History of Jemez Pueblo

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward, across the Upper San Juan River into the Gallina Highlands, then over the hill to the Canyon de San Diego area in the southern Jemez mountains. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa. The large migrations out of the Four Corners area began around 1250 and the area was almost entirely depopulated by 1300. The Towa-speakers who went southeast were pretty much settled by about 1350.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that pot sherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed by other Hopis around 1625). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, agriculture was hard. The Jemez had always been travelers and traders. Their people had traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico for generations. In those days they also made a lot of pottery and trading pottery with Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos for food was a brisk business.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and helped evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains.

It was around that time that the Hopi themselves destroyed Awatovi, the largest pueblo in the Hopi area (many of the people of Awatovi also spoke Towa). A Spanish missionary with a few soldiers had appeared at Awatovi in 1696 and forced the rebuilding of the mission. He also started getting people into the church. The leader of Awatovi went to the other Hopi pueblos and told their leaders that his people had strayed too far: they must be destroyed to cleanse the Earth of their sins. In the winter of 1700-1701, men from Walpi, Oraibi and a couple other pueblos invaded Awatovi while the men were in their kivas. The invaders pulled the ladders out of the kivas, poured baskets of hot red chile peppers and burning pine pitch down, then killed almost everyone. When the frenzy was over they burned the pueblo down and salted the earth around it so it would never be reoccupied.

On their return to the Jemez Mountains around 1700, the Jemez people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities. Even today, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Dineh territory at Jeddito.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Pecos Pueblo (more properly known as Cicuyé) are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé were the easternmost speakers of the Towa language in the Southwest. After the Pueblo Revolt, the Pecos area fell on increasingly hard times (constant Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, increasing drought). The pueblo was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents relocated to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Pecos tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Pecos families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Jemez Pueblo Pottery

Some of the Towa-speaking people had been making a type of plainware pottery (simple, undecorated, utilitarian) when they were still in the Four Corners area, while others had developed a distinctive style of black geometric designs on white pottery. In migrating to the Jemez Mountains, they brought their knowledge and techniques with them but had to adapt to the different materials available to work with. Over time, the Jemez got better in their agricultural practices and began trading agricultural goods to the people of Zia Pueblo in return for pottery. The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for them and by the mid-1700s, the Jemez were producing almost no pottery of their own. After the Americans took over, whatever pottery was discovered in official excavations of abandoned Jemez pueblos was removed to the basement of a museum somewhere else. The Jemez were relieved of virtually all their patrimony this way.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Cicuyé (Pecos) Pueblo are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé, with a couple smaller outlying pueblos in the Galisteo Basin, were the only other speakers of the Towa language in New Mexico. When that area fell on increasingly hard times (Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, drought), Cicuyé was abandoned. That happened in 1838 when the last 17 residents moved to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Cicuyé families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

When general American interest in Puebloan pottery started to take off in the 1960s, the people of Jemez sought to recover that lost heritage. Today, the practice of traditional pottery-making is very much alive and well among the Jemez.

The focus of Jemez pottery today has turned to the making of storytellers, an art form that now accounts for more than half of their pottery production. Storytellers are usually grandparent figures with the figures of children attached to their bodies. The grandparents are pictured orally passing tribal songs and histories to their descendants. While this visual representation was first created at Cochiti Pueblo (a site in close geographical proximity to Jemez Pueblo) in the early 1960s by Helen Cordero, it speaks to the relationship between grandparents and grandchildren of every culture.

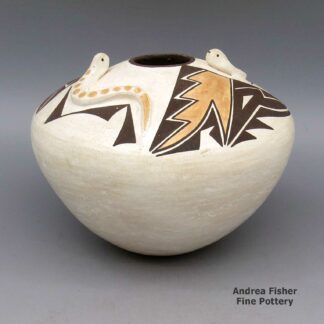

The pottery vessels made at Jemez Pueblo today are no longer black-on-white. Instead, the potters have adopted many colors, styles and techniques from other pueblos to the point where Jemez potters no longer have one distinct style of their own beyond that which stems naturally from the materials they themselves acquire from their surroundings: it doesn’t matter what the shape or design is, the clay says uniquely "Jemez".

About Bowls

The bowl is a basic utilitarian shape, a round container more wide than deep with a rim that is easy to pour or sip from without spilling the contents. A jar, on the other hand, tends to be more tall and less wide with a smaller opening. That makes the jar better for cooking or storage than for eating from. Among the Ancestral Puebloans both shapes were among their most common forms of pottery.

Most folks ate their meals as a broth with beans, squash, corn, whatever else might be in season and whatever meat was available. The whole village (or maybe just the family) might cook in common in a large ceramic jar, then serve the people in their individual bowls.

Bowls were such a central part of life back then that the people of the Classic Mimbres society even buried their dead with their individual bowls placed over their faces, with a "kill hole" in the bottom to let the spirit escape. Those bowls were almost always decorated on the interior (mostly black-on-white, color came into use a couple generations before the collapse of their society and abandonment of the area). They were seldom decorated on the exterior.

It has been conjectured that when the great migrations of the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th centuries were happening, old societal structures had to change and communal feasting grew as a means to meet, greet, mingle with and merge newly arrived immigrants into an already established village. That process called for larger cooking vessels, larger serving vessels and larger eating bowls. It also brought about a convergence of techniques, styles, decorations and design palettes as the people in each locality adapted. Or didn't: the people in the Gallina Highlands were notorious for their refusal to adapt and modernize for several hundred years. They even enforced a No Man's Land between their territory and that of the Great Houses of Chaco Canyon, killing any and all foreign intruders. Eventually, they seem to have merged with the Towa as those people migrated from the Four Corners area to the southern Jemez Mountains.

Traditional bowls lost that societal importance when mass-produced cookware and dishware appeared. But, like most other Native American pottery in the last 150 years, market forces caused them to morph into artwork.

Bowls also have other uses. The Zias and the Santo Domingos are known for their large dough bowls, serving bowls, hair-washing bowls and smaller chili bowls. Historically, these utilitarian bowls have been decorated on their exteriors. More recently, they've been getting decorated on the interior, too.

The bowl has also morphed into other forms, like Marilyn Ray's Friendship Bowls with children, puppies, birds, lizards and turtles playing on and in them. Or Betty Manygoats' bowls encrusted with appliqués of horned toads or Reynaldo Quezada's large, glossy black corrugated bowls with custom ceramic black stands.

When it comes to low-shouldered but wide circumference ceramic pieces (such as many Sikyátki-Revival and Hawikuh-Revival pieces are), are those jars or bowls? Conjecture is that the shape allows two hands to hold the piece securely by the solid body while tipping it up to sip or eat from the narrower opening. That narrower opening, though, is what makes it a jar. The decorations on it indicate that it is more likely a serving vessel than a cooking vessel.

This is where our hindsight gets fuzzy. In the days of Sikyátki, those potters used lignite coal to fire their pieces. That coal made a hotter fire than wood or manure (which wasn't available until the Spanish brought it). That hotter fire required different formulations of temper-to-clay and mineral paints. Those pieces were perhaps more solid and liquid resistant than most modern Hopi pottery is: many Sikyátki pieces survived intact after being slowly buried in the sand and exposed to the desert elements for hundreds of years. Many others were broken but were relatively easy to reassemble as their constituent pieces were found all in one spot and they survived the elements. Today's pottery, made the traditional way, wouldn't survive like that. But that ancient pottery might have been solid enough to be used for cooking purposes, back in the day.

About Sgraffito Designs

"Sgraffito" is from the Italian, meaning "to scratch." It's a technique wherein designs are scratched into the surface of a piece of pottery, generally with the use of a needle, dental tool or other sharp object. Also usually, the surface of the piece has been slipped with one color of clay and scratching through it reveals the design in a different color of clay. Some potters will slip a piece with layers of various colors of clay and the depth of their etching gives a color depth to their designs. Some will fire their pieces first, using the firing process to produce different effects in the clay. When they etch them after, the different depths they etch to also lend a color depth to their designs.

The sgraffito technique has been widely used in Europe for centuries but only came to the pueblos in the late 1960s. Even then, it's only really been developed at Jemez, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso and Ohkay Owingeh. At Santa Clara, Joseph Lonewolf and his father, Camilio Tafoya, and sister, Grace Medicine Flower, have been credited as being among the first to develop sgraffito. Corn Moquino was there, too, in those early days. At San Ildefonso, Juan Tafoya and Barbara Gonzales were among the first. At Ohkay Owingeh, Alvin Curran and Tom Tapia were among the first. Juanita Fragua was among the earliest at Jemez.

In Mata Ortiz, virtually anything goes and sgraffito has been widely used since the early 1970s. Again, some potters scratch their designs before firing, some after. Some scratch to add textured designs to an otherwise same-colored surface. Some carve and scratch and then fire. Some carve, paint and fire, then scratch... The tools they use vary from dental picks and exacto knives to nails, file handles and sharpened bicycle spokes.