| Dimensions | 5 × 5 × 4 in |

|---|---|

| Condition of Piece | Excellent |

| Signature | Wilma Baca-Tosa Jemez N.M. |

| Date Born | 2023 |

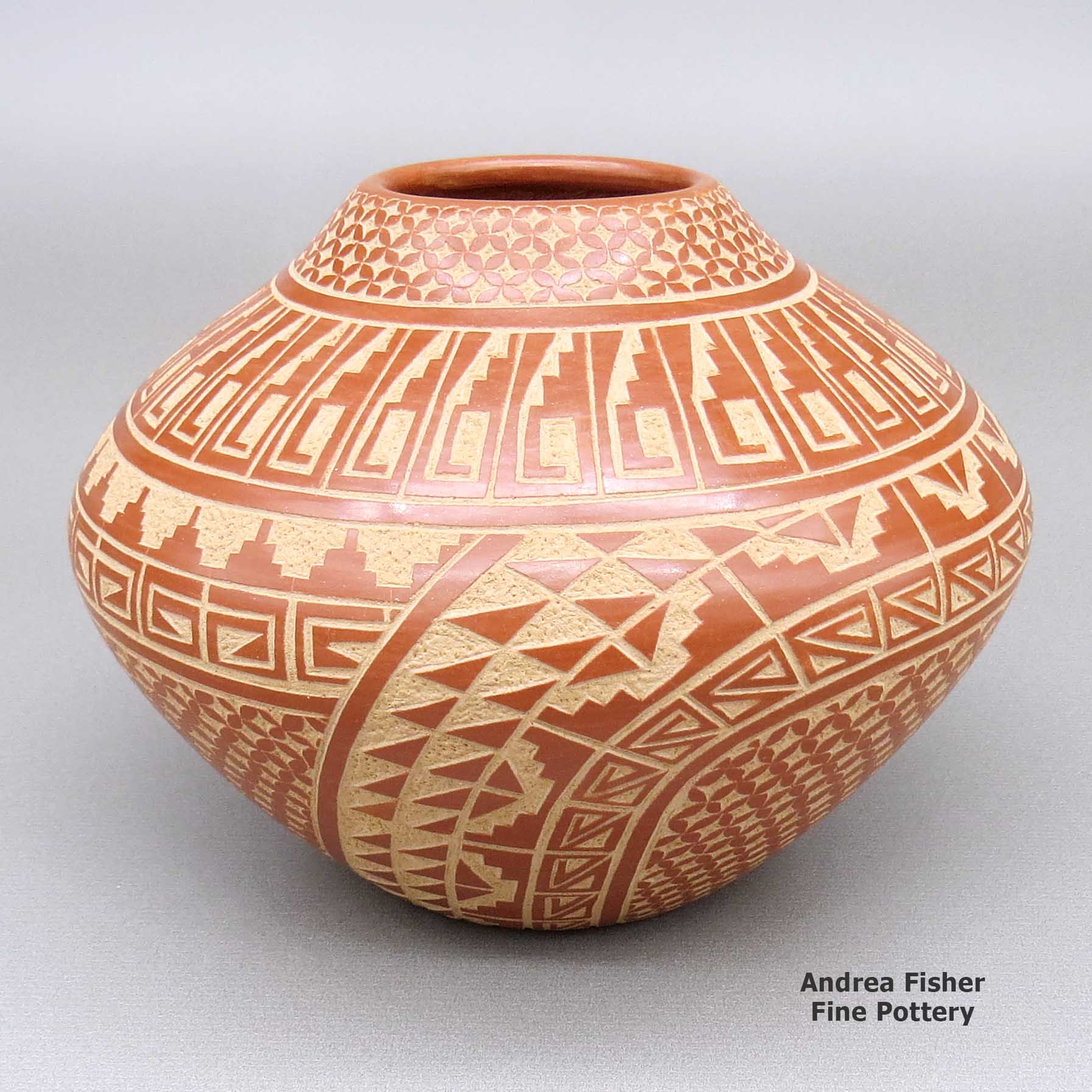

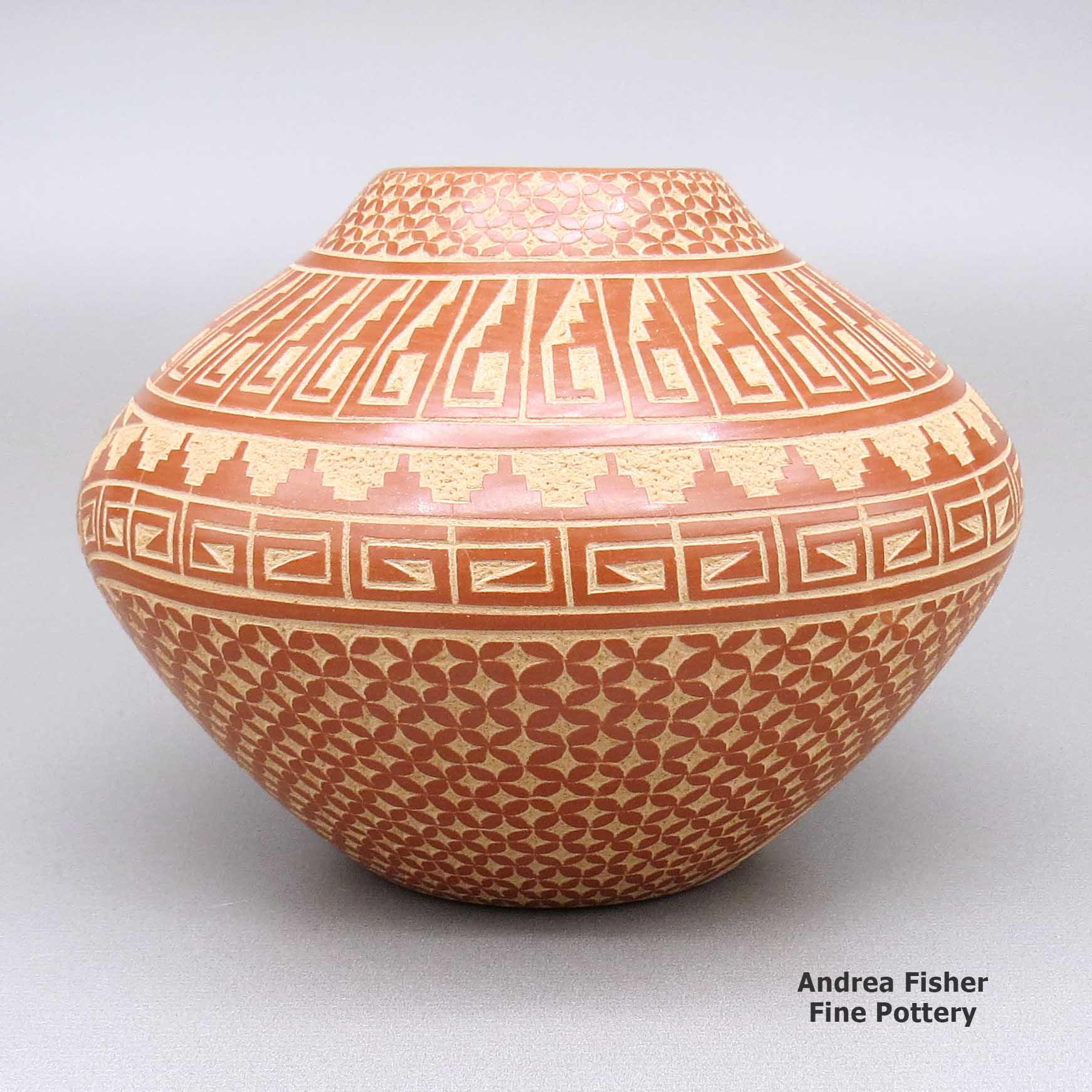

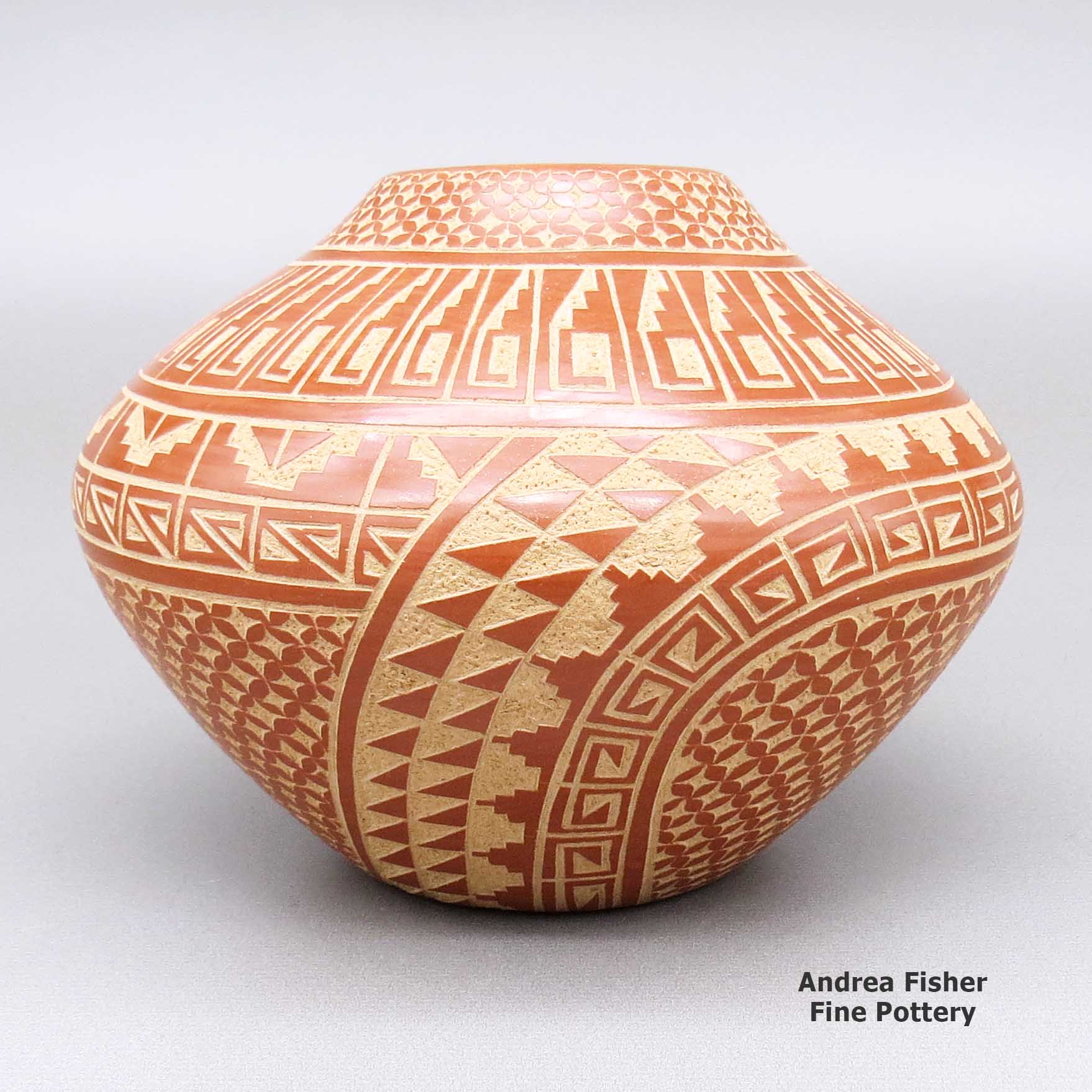

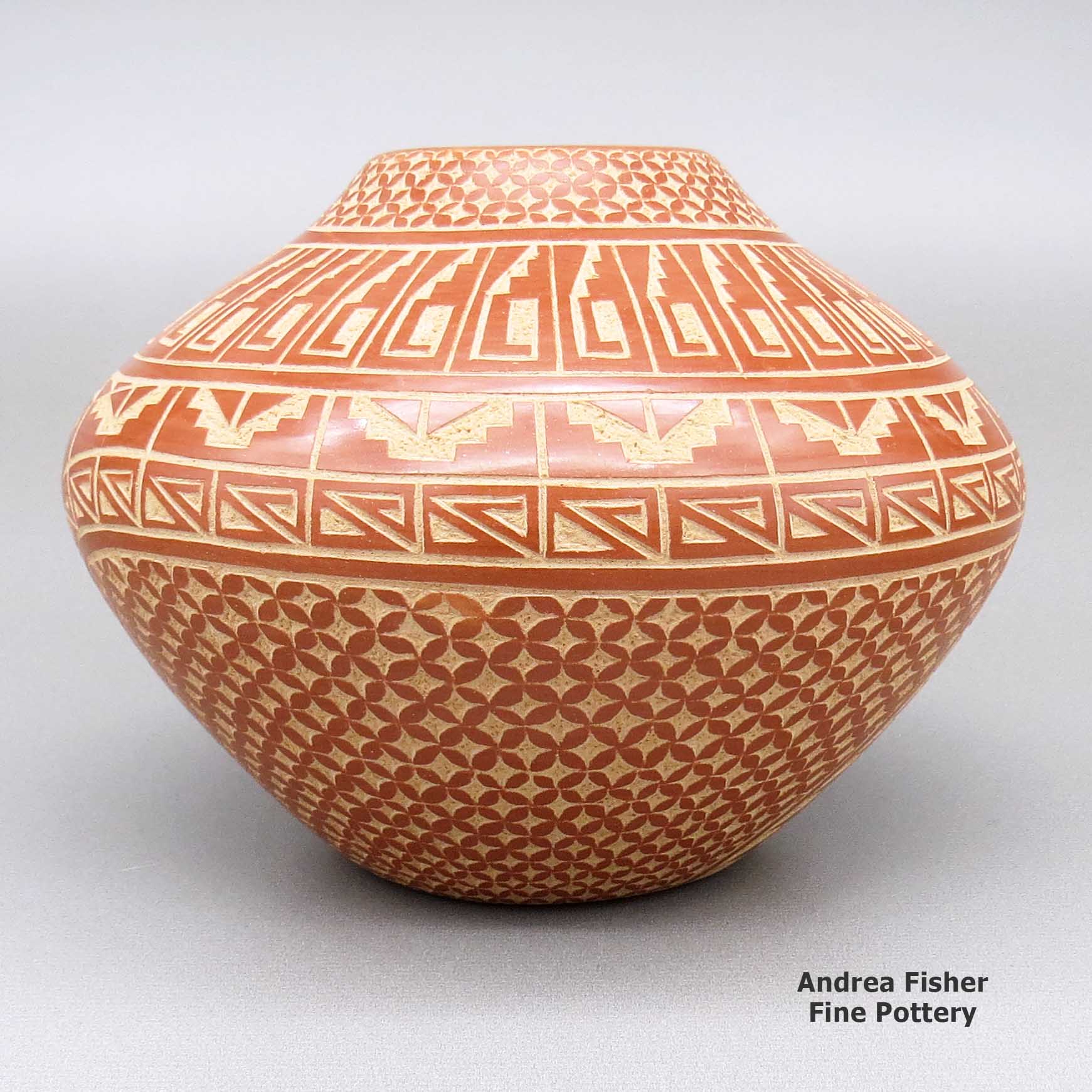

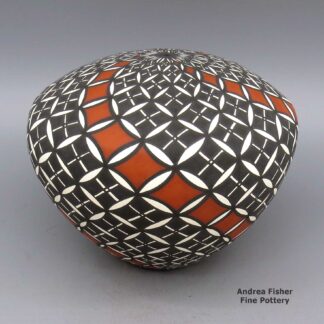

Wilma Baca Tosa, zzje3b181, Jar with kiva step and geometric design

$675.00

A red jar decorated with a sgraffito kiva step, snowflake and geometric design

In stock

Brand

Tosa, Wilma Baca

Wilma Baca, (New Wheat), was born to John and Linda Baca in Jemez Pueblo in September 1967. By the time she was five, she already had her hands in the clay. Her grandmother, Marie Reyes Shendo, saw that and took Wilma under her wing.

Wilma Baca, (New Wheat), was born to John and Linda Baca in Jemez Pueblo in September 1967. By the time she was five, she already had her hands in the clay. Her grandmother, Marie Reyes Shendo, saw that and took Wilma under her wing.Marie had been one of the original potters in the 1920s attempt to revive the Jemez pottery tradition. She taught Wilma the fundamentals of making pottery the traditional way using ancient methods passed down from their ancestors.

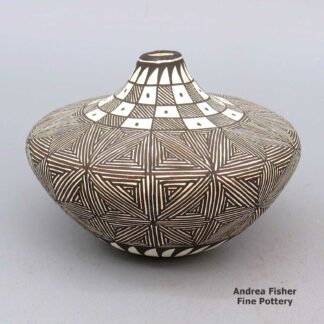

Wilma specializes in hand coiled, stone polished and traditionally decorated Jemez pottery. She makes redware bowls, jars, seed pots, vases and wedding vases.

Wilma has been etching her pottery using the free-hand sgraffito technique since 1989. Her favorite piece to make is the wedding vase because of its meaning: "The spouts represent two separate lives, the bridge across the middle unites these separate lives as one," she says.

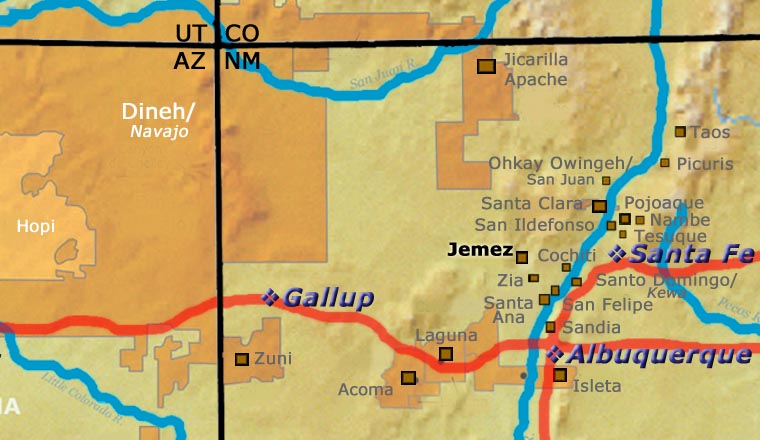

A Short History of Jemez Pueblo

As the drought in the Four Corners region deepened in the late 1200s, several clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southeastward, across the Upper San Juan River into the Gallina Highlands, then over the hill to the Canyon de San Diego area in the southern Jemez mountains. Other clans of Towa-speaking people migrated southwest and settled in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona, below Antelope Mesa and southeast of Hopi First Mesa. The large migrations out of the Four Corners area began around 1250 and the area was almost entirely depopulated by 1300. The Towa-speakers who went southeast were pretty much settled by about 1350.

Archaeologist Jesse Walter Fewkes argues that pot sherds found in the vicinity of the ruin at Sikyátki (near the foot of Hopi First Mesa) speak to the strong influence of earlier Towa-speaking potters on what became "Sikyátki Polychrome" pottery (Sikyátki was a village at the foot of First Mesa, destroyed by other Hopis around 1625). Fewkes maintained that Sikyátki Polychrome pottery was the finest ceramic ware ever made in prehistoric North America.

Francisco de Coronado and his men arrived in the Jemez Mountains of Nuevo Mexico in 1539. By then the Jemez people had built several large masonry villages among the canyons and on some high ridges in the area. Their population was estimated at about 30,000 and they were among the largest and most powerful tribes in northern New Mexico. Some of their pueblos reached five stories high and contained as many as 3,000 rooms.

Because of the nature of the landscape they inhabited, agriculture was hard. The Jemez had always been travelers and traders. Their people had traded goods all over the Southwest and northern Mexico for generations. In those days they also made a lot of pottery and trading pottery with Zia and Santa Ana Pueblos for food was a brisk business.

The arrival of the Spanish was disastrous for the Jemez and they resisted the Spanish with all their might. That led to many atrocities against the tribe until they rose up in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and helped evict the Spanish from northern New Mexico. With the Spanish gone, the Jemez destroyed much of what they had built on Jemez land. Then they concentrated on preparing themselves for the eventual return of the hated priests and the Spanish military.

The Spanish returned in 1692 and their efforts to retake northern New Mexico bogged down as the Jemez fought them doggedly for four years. In 1696 many Jemez came together, killed a Franciscan missionary and then fled to join their distant relatives in the Jeddito Wash area in northeastern Arizona. They remained at Jeddito Wash for several years before returning to the Jemez Mountains.

It was around that time that the Hopi themselves destroyed Awatovi, the largest pueblo in the Hopi area (many of the people of Awatovi also spoke Towa). A Spanish missionary with a few soldiers had appeared at Awatovi in 1696 and forced the rebuilding of the mission. He also started getting people into the church. The leader of Awatovi went to the other Hopi pueblos and told their leaders that his people had strayed too far: they must be destroyed to cleanse the Earth of their sins. In the winter of 1700-1701, men from Walpi, Oraibi and a couple other pueblos invaded Awatovi while the men were in their kivas. The invaders pulled the ladders out of the kivas, poured baskets of hot red chile peppers and burning pine pitch down, then killed almost everyone. When the frenzy was over they burned the pueblo down and salted the earth around it so it would never be reoccupied.

On their return to the Jemez Mountains around 1700, the Jemez people built the pueblo they now live in (Walatowa: The Place) and made peace with the Spanish authorities. Even today, there are still strong ties between the Jemez and their cousins on Dineh territory at Jeddito.

East of what is now Santa Fe is where the ruins of Pecos Pueblo (more properly known as Cicuyé) are found. Cicuyé was a large pueblo housing up to 2,000 people at its height. The people of Cicuyé were the easternmost speakers of the Towa language in the Southwest. After the Pueblo Revolt, the Pecos area fell on increasingly hard times (constant Apache and Comanche raids, European diseases, increasing drought). The pueblo was finally abandoned in 1838 when the last 17 residents relocated to Jemez. The Governor of Jemez welcomed them and allowed them to retain many of their Pecos tribal offices (governorship and all). Members of former Pecos families still return to the site of Cicuyé every year to perform religious ceremonies in honor of their ancestors.

For more info:

Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-0, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Prehistoric Hopi Pottery Designs, Jesse Walter Fewkes, ISBN-0-486-22959-9, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973

Photos are our own. All rights reserved.

About Jars

The jar is a basic utilitarian shape, a container generally for cooking food, storing grain or for carrying and storing water. The jar's outer surface is a canvas where potters have been expressing their religious visions and stories for centuries.

In Sinagua pueblos (in northern Arizona), the people made very large jars and buried them up to their openings in the floors of the hidden-most rooms in their pueblo. They kept those jars filled with water but also kept smaller jars of meat and other perishables inside those jars in the water. It's a form of refrigeration still in use among indigenous people around the world.

Where bowls tend to be low, wide and with large openings, jars tend to be more globular: taller, less wide and with smaller openings.

For a potter looking at decorating her piece, bowls are often decorated inside and out while most jars are decorated only on the outside. Jars have a natural continuity to their design surface where bowls have a natural break at the rim, effectively yielding two design surfaces on which separate or complimentary stories can be told.

Before the mid-1800s, storage jars tended to be quite large. Cooking jars and water jars varied in size depending on how many people they were designed to serve. Then came American traders with enameled metal cookware, ceramic dishes and metal eating utensils...Some pueblos embraced those traders immediately while others took several generations to let them and their innovations in. Either way, opening those doors led to the virtual collapse of utilitarian pottery-making in most pueblos by the early 1900s.

In the 1920s there was a marked shift away from the machinations of individual traders and more toward marketing Native American pottery as an artform. Maria Martinez was becoming known through her exhibitions at various major industrial fairs around the country and Nampeyo of Hano was demonstrating her art for the Fred Harvey Company at the Grand Canyon. The first few years of the Santa Fe Indian Market helped to solidify that movement and propel it forward. It took another couple generations of artists to open other venues for their art across the country and turn Native American art into the phenomenon it has become.

Today's jars are artwork, not at all for utilitarian purposes, and their shapes, sizes and decorations have evolved to reflect that shift.

About Geometric Designs

"Geometric design" is a catch-all term. Yes, we use it to denote some kind of geometric design but that can include everything from symbols, icons and designs from ancient rock art to lace and calico patterns imported by early European pioneers to geometric patterns from digital computer art. In some pueblos, the symbols and patterns denoting mountains, forest, wildlife, birds and other elements sometimes look more like computer art that has little-to-no resemblance to what we have been told they symbolize. Some are built-up layers of patterns, too, each with its own meaning.

"Checkerboard" is a geometric design but a simple black-and-white checkerboard can be interpreted as clouds or stars in the sky, a stormy night, falling rain or snow, corn in the field, kernels of corn on the cob and a host of other things. It all depends on the context it is used in, and it can have several meanings in that context at the same time. Depending on how the colored squares are filled in, various basket weave patterns can easily be made, too.

"Cuadrillos" is a term from Mata Ortiz. It denotes a checkerboard-like design using tiny squares filled in with paints to construct larger patterns.

"Kiva step" is a stepped geometric design pattern denoting a path into the spiritual dimension of the kiva. "Spiral mesa" is a similar pattern, although easily interpreted with other meanings, too. The Dineh have a similar "cloud terrace" pattern.

That said, "geometric designs" proliferated on Puebloan pottery after the Spanish, Mexican and American settlers arrived with their European-made (or influenced) fabrics and ceramics. The newcomers' dinner dishes and printed fabrics contributed much material to the pueblo potters design palette, so much and for so long that many of those imported designs and patterns are considered "traditional" now.