A Short History of Santa Clara Pueblo

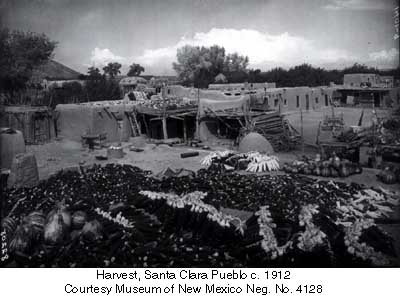

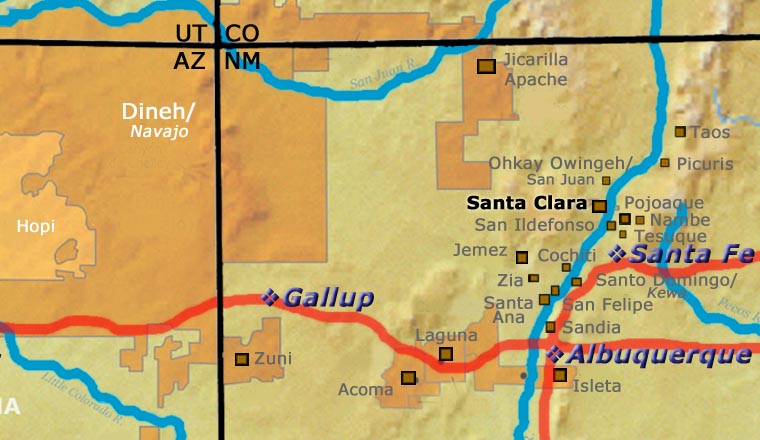

Santa Clara Pueblo straddles the Rio Grande about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. Of all the pueblos, Santa Clara has the largest number of potters.

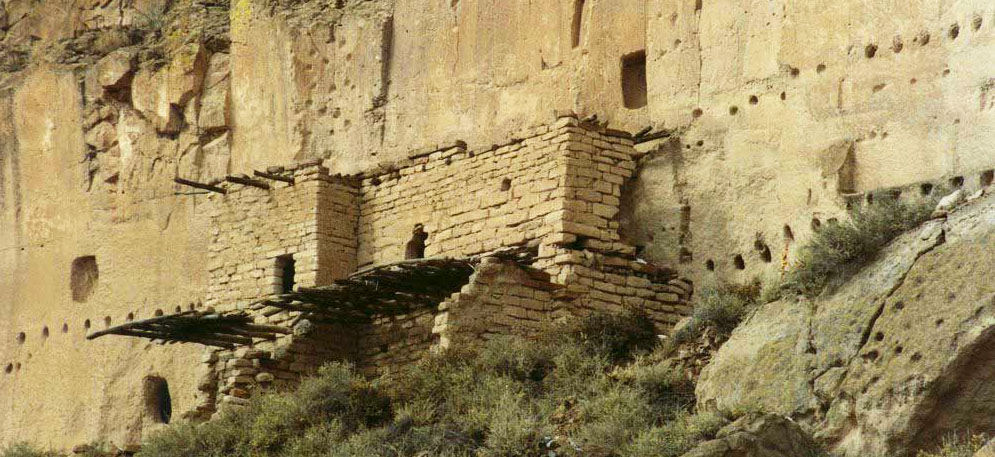

The ancestral roots of the Santa Clara people have been traced to ancient pueblos in the Mesa Verde region in southwestern Colorado. When the weather in that area began to get dry between about 1100 and 1300 CE, some of the people migrated to the Chama River Valley and constructed Poshuouinge (about 3 miles south of what is now Abiquiu on the edge of the mesa above the Chama River). Eventually reaching two and three stories high with up to 700 rooms on the ground floor, Poshuouinge was inhabited from about 1375 CE to about 1475 CE.

Drought then again forced the people to move. One group of the people went to the area of Puyé (along Santa Clara Canyon, cut into the eastern slopes of the Pajarito Plateau of the Jemez Mountains). Another group went south of there to what we now call Tsankawi. A third group went a bit to the north, following the Rio Chama down to where it met the Rio Grande and founded Ohkay Owingeh on the northwest side of that confluence.

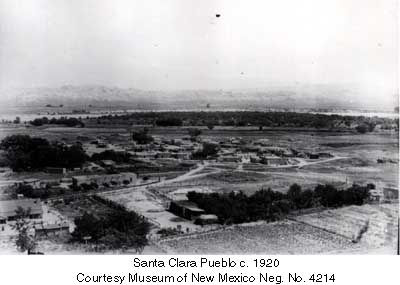

Beginning around 1580, another drought forced the residents of the Puyé area to relocate closer to the Rio Grande. There, near the point where Santa Clara Creek merged into the Rio Grande, they founded what we now know as Santa Clara Pueblo. Ohkay Owingeh was to the north on the other side of the Rio Chama. That same dry spell forced the people down the hill from Tsankawi to the Rio Grande where they founded San Ildefonso Pueblo to the south of Santa Clara, on the other side of Black Mesa.

In 1598 Spanish colonists from nearby Yunqué (the seat of Spanish government near the renamed "San Juan de los Caballeros" Pueblo) brought the first missionaries to Santa Clara. That led to the first mission church being built around 1622. However, the Santa Clarans chafed under the weight of Spanish rule like the other pueblos did and were in the forefront of the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. One pueblo resident, a mixed black and Tewa man named Domingo Naranjo, was one of the rebellion's ringleaders.

When Don Diego de Vargas came back to the area in 1694, he found most of the Santa Clarans were set up on top of nearby Black Mesa (with the people of San Ildefonso, Pojoaque, Tesuque and Nambé). An extended siege didn't subdue them but eventually, the two sides negotiated a treaty and the people returned to their pueblos. However, successive invasions and occupations by northern Europeans took their toll on the pueblos over the next 250 years. The Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 almost wiped them out.

Today, Santa Clara Pueblo is home to as many as 2,600 people and they comprise probably the largest per capita number of artists of any North American tribe (estimates of the number of potters run as high as 1-in-4 residents).

For more info:Pueblos of the Rio Grande, Daniel Gibson, ISBN-13:978-1-887896-26-9, Rio Nuevo Publishers, 2001

Upper photo courtesy of Einar Kvaran, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License

About the Pottery of Santa Clara Pueblo

At Santa Clara Pueblo, when it comes to pottery almost anything goes. Today's finished products tend to have a deep glossy red or deep glossy black surface. Santa Clara potters often paint, etch and carve those surfaces. Some don't, preferring instead the simple beauty of a plain, highly-polished, well-fired piece.

Santa Clara pottery runs the gamut from plates, bowls, seed pots and wedding vases to utensils, figures and sculptural pieces with inlaid stones. The normal at Santa Clara is to experiment until you find something that works, then experiment some more using that for a base.

The Santa Clarans moved to the junction of Santa Clara Creek and the Rio Grande in the late 1500s. Previously they had been at Puyé, several miles to the west up Santa Clara Canyon. They had been at Puyé for a couple hundred years. Before that they were in the Upper San Juan River Valley. Before that in the valley west of Mesa Verde in southwestern Colorado. They were painting black designs on white pottery there in the 1200s CE.

Some of the designs still in common use at Santa Clara can be traced back more than one thousand years to the Pueblo Bonito area in Chaco Canyon. Other designs can be traced back 900 years to the Mimbres culture of southern New Mexico. It seems virtually every innovation in traditional pottery-making over the last thousand years is still being practiced at Santa Clara. Santa Clara potters even remembered how to make black pottery when all the other pueblos forgot.

When Maria Martinez at San Ildefonso was commissioned by Edgar Hewitt to make black pottery, she tried but couldn't figure it out. So she went over to Santa Clara and asked Sarafina Tafoya how to do it. Sarafina showed her.

Santa Clara is still known for its polished blackware. Santa Clara potters were making the full complement of bowls, jars, canteens, plates, pitchers, tea pots, pipes and miniatures in the 19th century. When the railroad arrived at Espanola, virtually next door to the pueblo, the train depot became a favored place to sell their wares. Production exploded and new shapes and designs developed for the tourist market.

Around 1930 the Tafoya family began carving their pots. Previously they had pretty much stayed with impressing bear paw designs around the shoulders and necks of their pottery at most. Serafina's son Camilio and her son-in-law, Alcario, were both very good wood carvers and they started it.

Different styles of polychrome redware emerged in the 1920s and 1930s. In the early 1960s experiments with stone inlay, incising and double firing began. Modern potters have also extended the tradition with unusual shapes, slips and designs, illustrating what one Santa Clara potter said: "At Santa Clara, being non-traditional is the tradition." (This refers strictly to artistic expression; the method of creating pottery remains traditional).

In the late 1960s Joseph Lonewolf, Grace Medicine Flower, Camilio Tafoya, Corn Moquino and others got into sgraffito designs and that shortly took off, too.

Today, Santa Clara potters slip, carve, etch, paint, polish and fire their pottery to attain many different finishes, designs and feels. They are at the forefront of modern innovation using traditional materials and techniques.

Our Info Sources

Pueblo Indian Pottery, 750 Artist Biographies, by Gregory Schaaf, © 2000, Center for Indigenous Arts & Studies.

Some information may have been gleaned from Pottery by American Indian Women: Legacy of Generations, by Susan Peterson, © 1997, Abbeville Press.

Some info may be sourced from Fourteen Families in Pueblo Pottery, by Rick Dillingham, © 1994, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Other info may be derived from personal contacts with the potter and/or family members, old newspaper and magazine clippings, and through interminable searches of the Internet and cross-examination of any results returned.

Data is also checked against the Heard Museum's Native American Artists Resource Collection Online.

If you have any corrections or additional info for us to consider, please send it to: info@andreafisherpottery.com.